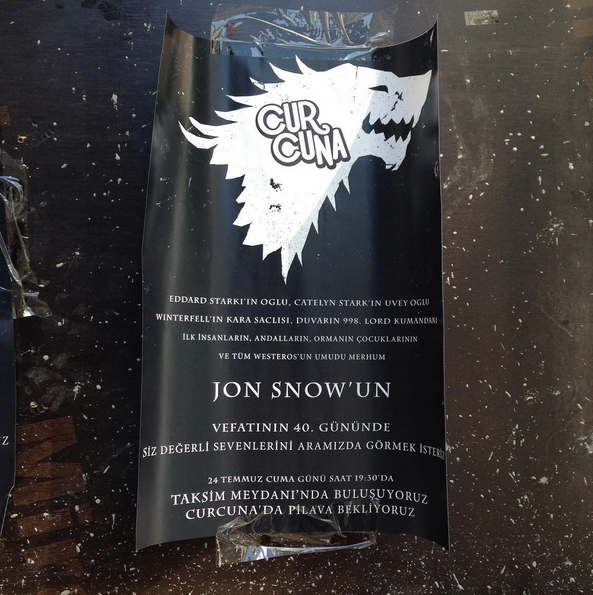

If you walk down the side streets of Istanbul you will see posters advertising any number of bad bars or worse politicians, all produced with the help of brazen copyright infringement. Knowing this, I wasn’t surprised to see a wolf head silhouette. It was the emblem of House Stark, the honorable family from the massively popular American show Game of Thrones.

I was a little surprised to see the name of a nightclub inscribed in the sigil; I used to work across the street from it, and I remembered long nights overlooking its empty bar and bored DJ. But the text stopped me cold in my tracks: “To commemorate 40 days since the death of Jon Snow, we ask his dear loved ones to join us”

The poster was made to look like a standard Turkish funerary invitation and invited mourners to the nightclub for a traditional rice dish. This invite, however, was to mourn Jon Snow, the natural son of Eddard Stark who became the 998th Lord Commander of the Night’s Watch. Also, a completely fictional character. The “40 days” counted down from the HBO airing of the finale and adhered to Muslim tradition. This meant that people in Turkey were pirating Game of Thrones in large enough numbers for a mediocre night club to try and ride its popularity. Not only that, they were also imbuing it with their own traditions.

Game of Thrones is wildly popular in Turkey. One fan has written a Türkü, or traditional Turkish ballad, to Jon Snow. Protesters use the show’s tagline, “Winter is Coming,” to poke fun at President Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan. And really bad bars are using the death of a beloved character to bring in a crowd. None of this could happen without a translator writing subtitles for the show. It turns out Turkey’s Game of Thrones mania is due to one college student. He goes by the Twitter handle of @esekherif_.

“It was 2005 or 2006, I think, when broadband Internet became a thing everyone could own” recalls Cem Özdemir. He is esekherif_ online and a student in the analog world. It should come as no surprise that he’s set to graduate from the Hacettepe Department of Translation and Interpretation in Ankara, the nation’s capital.

In an interview with Ajam MC, Özdemir cites Prison Break as his gateway drug, an American-style drama with high production values and tons of intrigue. “Some of our networks were showing these shows,” but they were watered down by the country’s prudish television authorities. “The subtitle or dubbing was always censored in one way or another.”

Broadband internet meant that Turks could pirate the original American episodes, but they still relied on translators to write and upload Turkish subtitles. As Özdemir tells it, “That’s where I come in.”

“I started translating subtitles in 2008 when I was 17, just out of curiosity. I wanted to see if I could do this. It was a volunteer, even philanthropist thing which was people just ‘helping’ other people to watch some great shows and movies.”

Early results were not promising. “I sucked at my first subtitle,” he remembers. According to Özdemir, it couldn’t even be given away for free — the subtitle was removed from Divxplanet, the forum that hosts subtitles for pirated shows. But he worked hard (and switched majors from physics to translation). In 2011, Divxplanet moderators asked Özdemir to lead translations for Game of Thrones. He was 20 years old.

It isn’t like Turkey was walled off from American cultural artifacts before the Internet. Plenty of movies, TV shows, and songs crossed the Atlantic. They were often dubbed or highly edited, and they weren’t the only cultural imports. James Baldwin visited and Eartha Kitt sang about Üsküdar.

American superhero brands were popular in Istanbul throughout the 1970s, but it always seemed like something was lost in translation. In the 1970s, Captain America was called into Istanbul to rescue Turks from a villainous Spiderman. Levent Çakır played a stiff Betmen — so titled to avoid confusion with the southeastern Turkish city of Batman. Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam, known as Turkish Star Wars, was reviewed by one American as “jaw-droppingly insane.”

The films were part of Turkey’s golden era of Yeşilçam cinema, so named after a street in Istanbul where many production companies were based. The authorities revelled in this local industry and their production of an approved aesthetic. Early on, producers realized superheroes fit the preferred tropes. The villain lost and the good guy got the girl – preferably Turkey’s sweetheart, Türkan Şoray.

The problems came when Yeşilçam directors realized what sold better than American stories made on the cheap. Namely, porn. According to journalist Clement Girardot, cinema houses tried to compete with TV dramas by producing steamier films with no-name actors. Thus came the Seks Furyası – “Sex Boom” – and by 1979 over two-thirds of the 193 films made in Turkey were erotic in nature.

A 1980 coup toppled not just the Turkish government, but also the supposedly “immoral” film industry. Many of the biggest players in Yeşilçam were jailed and Turkey began importing its movies and producing more wholesome dramas.

Today, Turkey’s movie and television industry is booming. Turkish soap operas have been syndicated in Arab countries, Latin America, and South Asia. Turkish cinema is a cultural export too. But American shows like Game of Thrones are still very popular in Turkey, and they target different audiences than the Turkish-made shows.

“I don’t watch any Turkish series,” states Özdemir. He has, however, subtitled over 500 episodes and films by his count. Mostly TV shows like Game of Thrones, Big Bang Theory, along with “a lot more I don’t even remember.”

He grew up reading the books Game of Thrones are based on (“I’ve read all the books like three times now”) and is very much at home in the universe built by American novelist George R.R. Martin. The show’s peculiar Dothraki language presents no problems. Not because it’s related to Turkish, as some fan conspirators believe, but because it has hard-coded English translations that Özdemir can work from.

Other American sensations have a specificity that is difficult to translate. “I would just love to translate House of Cards,” he said, but “the American political system is incredibly confusing and we don’t have the equivalent positions and names. It’s one of those shows that is just impossible to translate without a lost culture element.”

Better Caul Saul, about a crooked lawyer in Albuquerque, New Mexico? “It has some legal terms but in general, I don’t think it is difficult.”

Özdemir was ready for Game of Thrones’ Season 6 debut. He made his own teaser trailers and posted them to Facebook, essentially acting as a hypeman for a multi-million dollar HBO production. He referred to himself as a sort of cultural ambassador and a “writer/director actor” in an interview with a Turkish fantasy/science fiction fan site. His job is to make this American show make sense to the 1 million viewers he believes watch every episode he subtitles.

It’s not so different from the role the Yeşilçam directors found themselves in when they stuffed Levent Çakır into a Batman (or Betmen) costume. Except that Özdemir has the internet at his disposal and three-fourths of a college degree (he graduates in a few months) to back him up.

And meanwhile, those 1970s Turkish flicks have become cult classics in the US, with one blog calling Turkish Star Wars “the perfect party movie.” There’s clicks in making fun of these objectively bad movies, and good fun in revelling in the more absurd plot points. These aesthetes take these films out of context, removing them from the political situation that surrounded these movies — and ultimately endangered the Turkish film industry.

What follows is a weird sort of appropriation tug-of-war. Turks’ reimagining of American superheroes has been reclaimed by American film buffs. And Game of Thrones is now part of Turkish pop culture. As can be seen by the nightclub in mourning or on the front page of radical zine Penguen, bits of Game of Thrones have melded with elements of culture to create something uniquely Turkish.

The show’s probable English War of the Roses inspiration is irrelevant. But a slideshow can be made out of how an (Indian American) writer mapped Game of Thrones’ politics onto the Middle East. Jon Snow, who is surly and duty-bound and really handsome, is a character straight out of those 1970 Yeşilcam flicks. Judging by how audiences regard it, Game of Thrones is a Turkish show that happened to have been funded by an American company.

It couldn’t be done without people like Cem Özdemir, aka esekherif_. We went back-and-forth over how to translate his Twitter handle. Özdemir, with his immaculate English, suggested “jackass” but then said, “I don’t think that covers it.” Me, with my weak Turkish, offered “donkey dude.” Like a patient teacher, he instructed me to “look at the meaning…it has a benign side to it. And girls find it cute.”

We couldn’t come up with a good answer. Some things just can’t be translated.

No comments:

Post a Comment