|

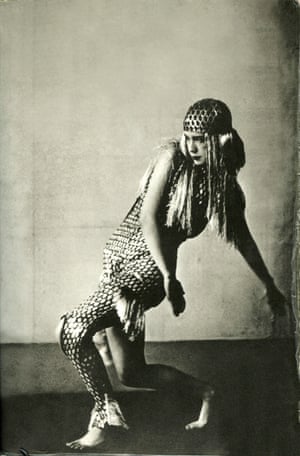

| The Joyces in Paris, 1924. From left, James, Nora, and their children, Lucia and George. |

Lucia by Alex Pheby review – in search of James Joyce’s daughter

This extraordinary novel inspired by the life of Lucia Joyce tells the troubling story of a woman who is confined and abused

Ian Sansom

Thu 12 July 2018

T

his book”, reads the prefatory note to Alex Pheby’s third novel, “is intended as a work of art. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in an artistic manner. Any representations of actual persons are either coincidental, or have been altered for artistic effect.” Erm, OK.

The Lucia of Pheby’s book is Lucia Joyce. She is a dancer, inmate of an asylum in Northampton, sister to George/Giorgio, niece to Stanislav, daughter of James and Nora, lover of artists … Sound familiar? The real LuciaJoyce was born in Trieste in 1907 and became a professional dancer. She was the lover of the artists Alexander Calder and Albert Hubbell. She died in 1982, having spent most of her adult life in psychiatric care, and more than 30 years in St Andrew’s Hospital in Northampton.

Pheby is not the first writer to have been drawn to Lucia. Her life has been the subject of a number of novels, plays, scholarly studies – and much speculation. What was the exact nature of her mental illness, if any? Was there abuse? Incest? Whose fault was it that she was confined and so poorly treated for so many years? The prefatory note to Pheby’s book suggests that answers to these questions remain contested. Some names and other details have been changed, and in one chapter, one name has been entirely redacted – whether the result of lawyers’ interventions or an act of literary licence, it is not entirely clear.

Pheby is a writer possessed of unusual – indeed, extraordinary – powers. His Lucia is a fully accomplished account of a troubled and troubling life. Most importantly, he does not spare himself from the accusations of appropriation and exploitation that are levelled throughout the book towards others. The chapters concerning Lucia are connected by short, apparently unrelated interludes about the opening up of a Pharaonic tomb, which are clearly intended as a commentary on Pheby’s own procedures. Is he anything more than another ghoulish grave-robber, a despoiler? “First, the corpse is eviscerated. They enter the skull by breaking the ethmoid bone with a metal implement, and stir the brain until it is liquid enough to be drained through the nose. The interior is then rinsed with palm wine and frankincense. Having no further use, the brain is discarded.”

The book focuses on the indignities wreaked on Lucia’s body – as a dancer, a lover, a patient, a woman, and as a subject for other writers. We first meet her “ready for the box”, a corpse in the Northampton asylum, “translucent and matt, dead to the touch, pliable and inelastic, utterly without substance”. We then see traces of her life being horribly extinguished by a nameless Joyce descendant – thousands of letters being burned, the ashes “smudged into everything” – before Pheby pieces together the remaining fragments of what may or may not have occurred during the course of her life. Furious and often disturbingly detailed, with accounts of asylum treatments using bovine serum and cold baths, the novel does not make for comfortable reading.

Pheby’s justification for inventing and imagining scenes of abuse is perfectly simple: “All things that are possible are, in the absence of facts that have been destroyed that might have proved them incorrect, equally correct.” Since all things are possible, all is permissible. Which was, of course, exactly the problem for Lucia among the Joyces and their associates.Of James Joyce: “Say he is sitting in the living room and there is the proper object of his affections – his wife, Nora – and he is aroused by her, but then she leaves while he is reading the paper, and you, Lucia, replace her in her chair. When he puts the paper down he sees you, in his state of arousal. Is it any wonder, in the blurry world in which he exists when he has his reading glasses in place rather than the glasses he has for distance, that his arousal is transferred to you?”Of Stanislav Joyce: “Also understand that a man’s brother will often have an unspoken desire for his brother’s wife, and what could be more natural? […] bearing in mind that a brother can never come between his brother and his wife … perhaps the girl?”

All the Joyces come off badly;Samuel Beckett comes off badly; so do Calder, Hubbell, the doctors and attendants in the asylum; and all the writers and readers who have followed in their wake, exhuming Lucia from her sarcophagus, examining her as if she were an exhibit. “Gawping wax-faced idiots who drag themselves past your body because they think it is the thing to do […] They watch through the glass, their desire for something of the afterlife, so prurient and formless, peering in the windows hoping for a glimpse of someone else’s death, to somehow understand what theirs might be.” Read this with your eyes wide open.

• Lucia is published by Galley Beggar Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment