Lesbians are like that because they're fat

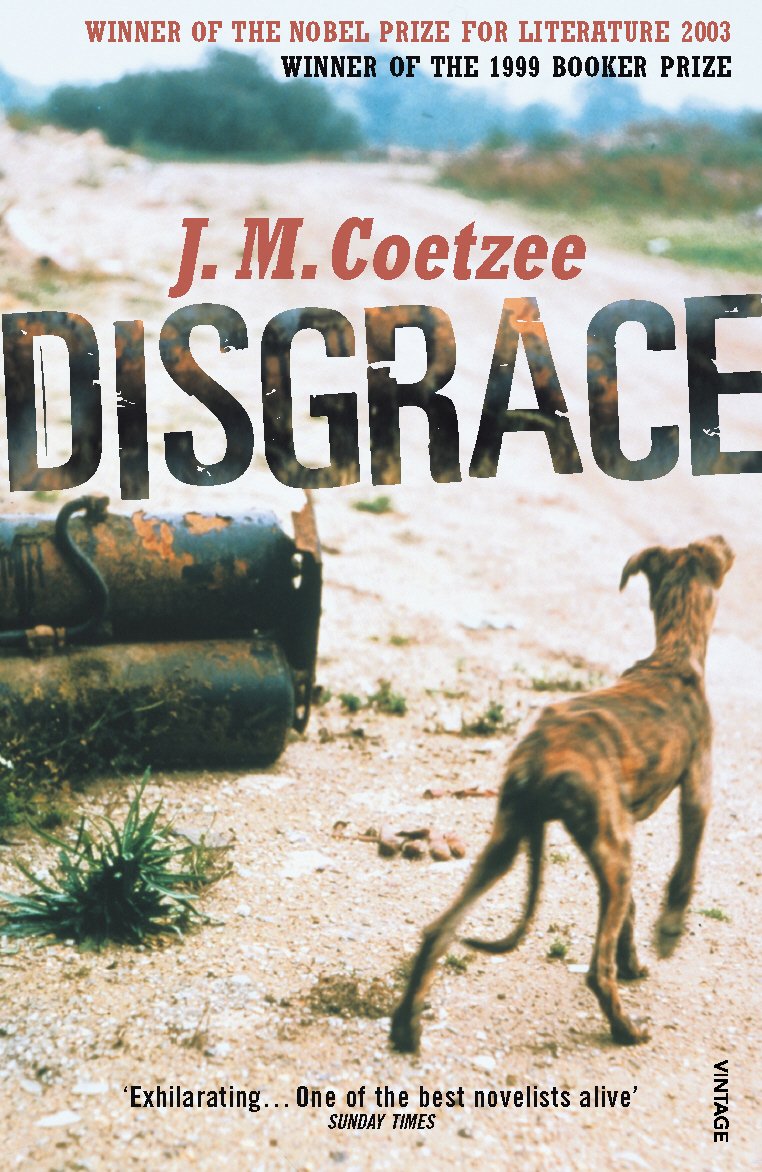

The 100 best novels / No 99 / Disgrace by JM Coetzee (1999)

Adam Mars-Jones

T

he novel may not inherently be a dialectical form, but readers are so used to a synthesising process that they may detect one without help from the author. JM Coetzee's quietly deceptive new novel exploits this reflex, with a narrative that belongs to two opposite types simultaneously, revealing its true allegiance only on the last page - in fact the last sentence.

David Lurie, a divorced university professor in his fifties, leaves Cape Town in disgrace to stay with his daughter Lucy on her smallholding in the Eastern Cape. What follows is somehow simultaneously a story of redemption and of collapse, just as a famous optical illusion is simultaneously a duck and a rabbit, but can only be seen at any one moment as one or the other. The reading mind responds to the possibilities in disconcerting alternation.

Lurie's disgrace is of a classic kind - an affair with a student - and he does nothing to protect himself from its consequences. It's as if he's promised himself a mid-life crisis and won't be denied one. He tries to see himself in wryly elevated terms, telling the investigating committee that he 'became a servant of Eros' rather than an abuser or even a harasser (his advances to a 20-year-old girl were in no way resisted). But it seems mere cussedness for him to refuse a compromise that would at least leave the possibility of a return to teaching.

Lurie was working on Byron at the time of his disgrace, and the irony is not particularly subtle that he comes to grief from an escapade that Byron would have thought distinctly timid. But there is a more disorientating irony than that. In the first chapter, it is explained that Lurie had his sex life satisfactorily worked out in his maturity, visiting a compatible prostitute every Thursday afternoon: '

His needs turn out to be quite light after all, light and fleeting, like those of a butterfly. No emotion, or none but the deepest, the most unguessed-at, like the hum of traffic that lulls the city-dweller to sleep, or like the silence of the night to countryfolk. No emotion, or the deepest.

It's only after he sees this woman out with her children, a chance encounter that somehow estranges her, that his love life is directed again towards women at large. At one, point desire is even described as a venom to be drawn. So how can Lurie be both a servant of Eros and a slave of libido? There isn't a lot of middle ground available

Before he leaves Cape Town, his daughter is referred to only as 'sole issue of his first marriage' - a legalistic formulation - but when he goes to stays with her in his disgrace, the feel ing-tone is different: 'From the day his daughter was born he has felt for her nothing but the most spontaneous, most unstinting love.' Love may be unstinting, but compatibility would have to be rated as low, she being, among other things, plump, lesbian and vegetarian. He speculates on a link between at least two of these terms - 'Sapphic love: an excuse for putting on weight.'

Those who require narratives of healing will find plenty of material from which to construct one: Lurie does some physical work for a change and comes to feel a connection with animals. He helps at a clinic of the Animal Welfare League and supervises the disposal of dogs which have been put down, briefly taking charge of a hospital incinerator each week. Since, otherwise, the attendants beat the black plastic bags of remains with their shovels, breaking the rigid limbs to make sure the dead dogs don't catch in the feeder trolley and ride back singed and grinning, the plastic burnt off. Now that Lurie has lost all dignity, he can try to watch over the dignity of those who never had it. In what could be construed as another breakthrough, since he dislikes women who make no attempt to attract, he sleeps with the notably plain woman who runs the clinic.

But there is also an opposite story, not running parallel to the other but built from the same set of materials. In this narrative, country life is not therapy but ordeal, not a pastoral but a war of attrition. In the new South Africa, the man who was once the kaffir calls the shots. His help must be asked for and his protection sought, particularly by a woman living alone, and it may be that his ambition is to take over the land rather than share it. All this is regarded as just, or at least historically inevitable, but there are patterns that seem to magnify and distort the minor disgrace that did for Lurie in the city; oppression from someone whose role is to protect, sexual predation without even his excuses.

Any novel set in post-apartheid South Africa is fated to be read as a political portrait, but the fascination of Disgrace - a somewhat perverse fascination, as some will feel - is the way it both encourages and contests such a reading by holding extreme alternatives in tension. Salvation, ruin. Even a single paragraph can accommodate the transformation of hope into its opposite, as when Lurie thinks of Lucy, now pregnant:

With luck, she will last a long time, long beyond him. When he is dead, she will, with luck, still be here doing her ordinary tasks among the flowerbeds. And from within her will have issued another existence, that with luck will be just as solid, just as long-lasting. So it will go on, a line of existences in which his share, his gift, will grow inexorably less and less, till it may as well be forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment