|

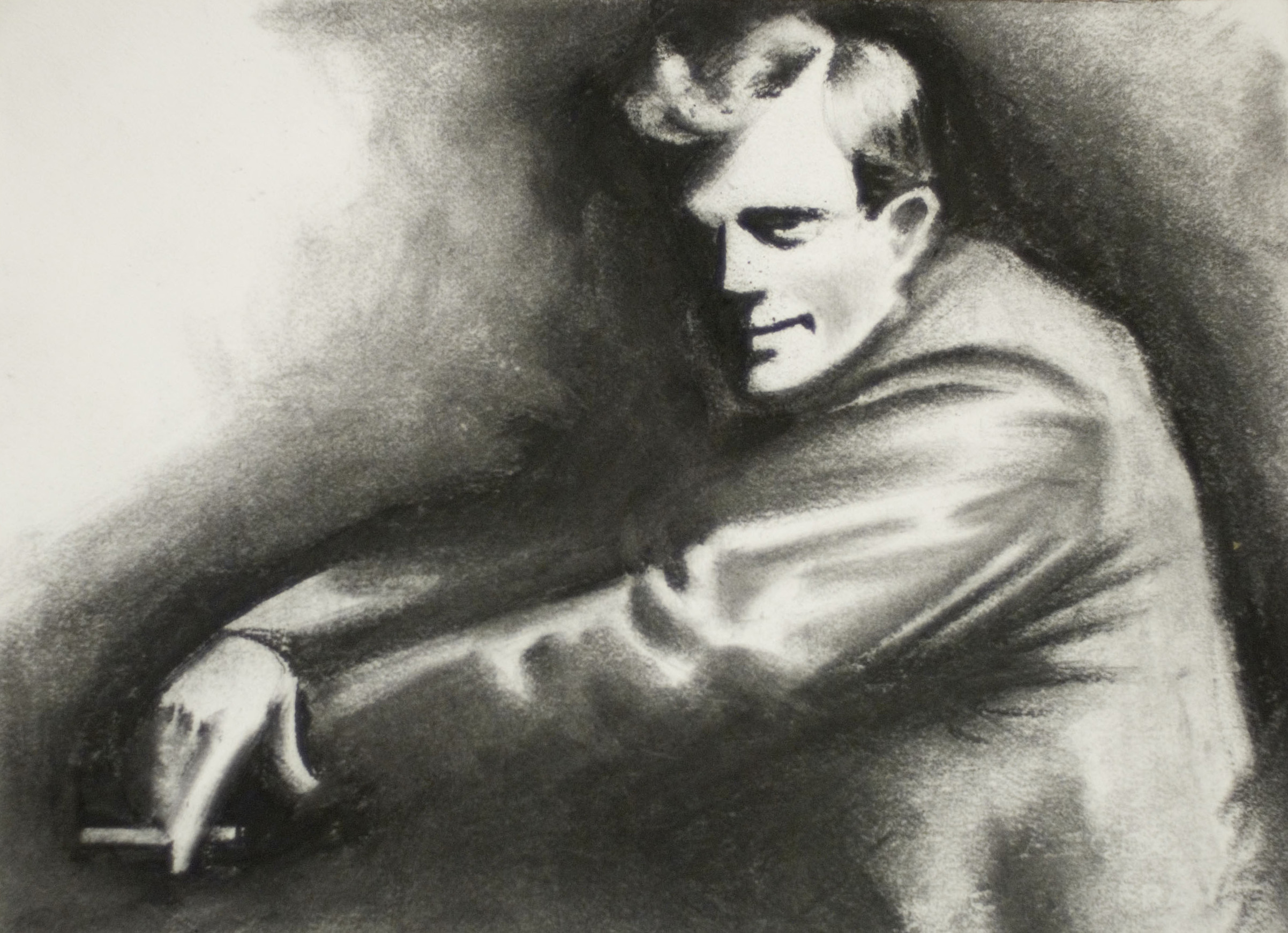

| Jack London by Jeremy Price |

Martin Eden: A Story of Failure – by Joan London

December 2, 2019

Of all Jack London’s serious works, none has been more widely misapprehended than Martin Eden, which he began to write soon after the Snark reached Honolulu. Most readers, ignoring the tragic ending which Jack deliberately conceived and logically reached for this novel, have regarded it solely as a “success” story. It has been known as the book which inspired not only a whole generation of young writers but others in different fields who, without aid or encouragement, attained their objectives through great struggle. Some people, completely identifying the author with his main character and forgetting Martin Eden’s scorn of socialism, believed his suicide to have been the result of his radical beliefs and, according to their own attitude, applauded or protested.

Jack himself was largely to blame for the mistaken impressions of his readers. In the copy of Martin Eden which he inscribed to Upton Sinclair he wrote, “One of my motifs, in this book, was an attack on individualism (in the person of the hero). I must have bungled, for not a single reviewer has discovered it.” Few discovered it for the simple reason that while Jack rejected individualism intellectually, his sympathy remained always with the individualist. Martin Eden’s struggle to rise from obscurity to fame was his own, and Jack was proud of both.

But one must seek deeper for the true cause of the confusion produced by this book. Up to a certain point Martin Eden was Jack London. They differed, according to Jack, in their attitude toward socialism. Martin Eden, the reactionary individualist, isolated from the vital force of a world-wide revolutionary movement that sought to destroy the regime which enslaved and crippled most of mankind, was doomed to disillusionment and bitterness, with suicide at the end. Jack, on the other hand, a Socialist with a warm interest in the fate of those less fortunate than himself, would escape this fate. So Jack reasoned. But it was selfdeception as futile as it was tragic, for even as he wrote Martin Eden, Jack’s isolation from the socialist movement had begun.

Brissenden, who was to Martin Eden what Strawn-Hamilton had been to Jack, said to Martin, “ ‘I’d like to see you a socialist before I’m gone. It will give you a sanction for your existence. It is the one thing that will save you in the time of disappointment that is coming to you. … You have health and much to live for, and you must be handcuffed to life somehow. As for me, you wonder why I am a socialist. I’ll tell you. It is because socialism is inevitable; because the present rotten and irrational system cannot endure; because the day is past for your man on horseback. … Of course I don’t like the crowd, but what’s a poor chap to do? We can’t have the man on horseback, and anything is preferable to the timid swine that now rule.’ ”

Jack had slipped his handcuffs. Never again, although he would talk much of socialism, would he be a participant in the socialist movement. His position during the next few years would be described today as that of a “sympathizer” on the “periphery,” although considering his income, he was not a generous contributor to the cause. And as other interests demanded more and more of his time, the distance between him and the socialist movement widened until he no longer felt its pulse beat, knew aught of its victories and defeats, or remembered its principles. When Jack’s “time of disappointment” came there was no longer any “sanction” for his existence.

As if he knew what the end of his life would be Jack London wrote his own obituary in Martin Eden, a story not of success, but of failure. At the same time, consciously deciding his future as a writer, Jack made of Martin Eden his salve atque vale to literature. The conclusions reached by Martin Eden when he questioned the validity of his popularity were Jack’s own rationalization of why he would never again exert himself artistically. “It was the bourgeoisie who bought his books,” reasoned Martin Eden and poured its gold into his money-sack, and from what little he knew of the bourgeoisie it was not clear to him how it could possibly appreciate or comprehend what he had written. His intrinsic beauty and power meant nothing to the hundreds of thousands who were acclaiming him and buying his books. He was the fad of the hour, the adventurer who had stormed Parnassus while the gods nodded.”

Source: Joan London, Jack London and his times, an unconventional biography, New York, Book League of America, 1939

No comments:

Post a Comment