|

| Anne Rice |

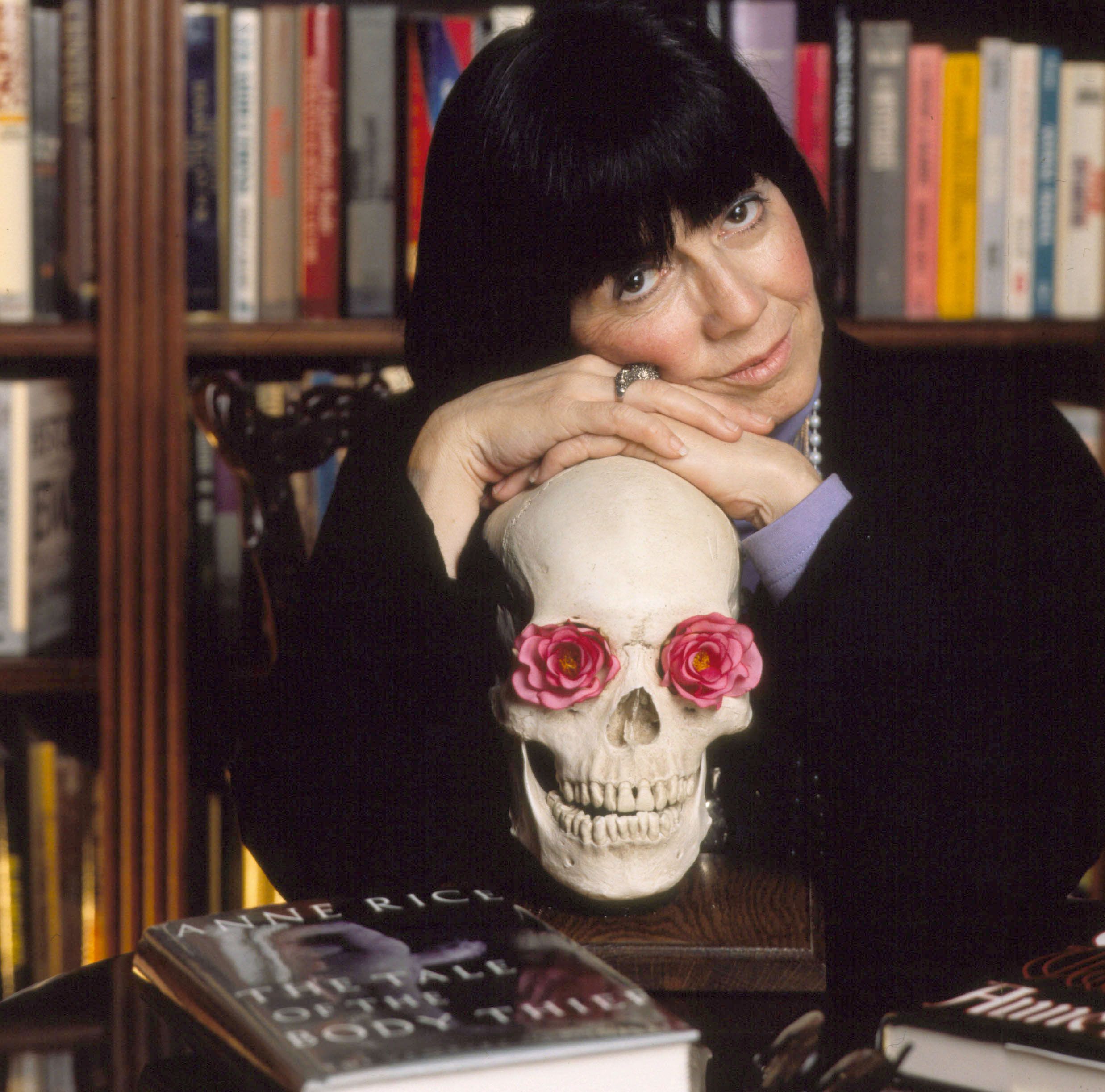

Anne Rice: Playboy Interview (1993)

A candid conversation with the author of The Vampire Chronicles about sex and violence, gays and bloodsuckers, and her helpful fans from the S&M scene

In 1976 Anne Rice came upon the literary scene with an extraordinarily innovative novel called “Interview with the Vampire.” Critics were not sure what to make of her richly imagined, deadly serious portrait of Lestat de Lioncourt—an 18th century vampire who poured out his tale of centuries on the run, of the eternal struggle between good and evil and of the meanings of death and immortality. But readers had no trouble seeing this vampire as an ultimate outsider—a symbolic figure for teens, gays and lonely urban apartment dwellers. It became an instant cult classic and the basis for a series of novels, “The Vampire Chronicles”—including “The Vampire Lestat,” “The Queen of the Damned” and, most recently, “The Tale of the Body Thief”—which have sold nearly 5 million copies.

The handful of critics who condemned “Interview with the Vampire” as a clever literary stunt could not have guessed how profoundly Rice identified with her fictional character’s emotions. For two years, she had watched helplessly as her only daughter, Michele, battled leukemia, dying before her sixth birthday. In her grief and frustration, she turned to alcohol and to marathon binges at the typewriter. The novel—which features a six-year-old vampire—emerged as a sort of catharsis. Prior to this crossroad in her life, Rice had been a “perpetual student” and aspiring writer who lived in the heart of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district during the rock-and-roll revolution of the Sixties.

Born on October 4, 1941, at Mercy Hospital in New Orleans, Anne was given the unusual name Howard Allen Frances O’Brien, incorporating her father’s first name and her mother’s maiden name. When she entered first grade in the Redemptorist Catholic School, she promptly announced that she would be known as Anne. Ghost stories and twilight walks through the cemeteries of New Orleans with her father made strong impressions on her as a child. So did the 1936 movie “Dracula’s Daughter,” which she recalls as the most vivid vampire imagery from her youth. She met her future husband, poet and artist Stan Rice, while both were working on a high school newspaper. After a long courtship, they married and went to San Francisco to attend college.

Her second published novel, “The Feast of All Saints, ” explored the New Orleans settings of her youth. Focusing on the relatively little-known experiences of the gens de couleur libre—the 18,000 blacks who lived as free men and women prior to the Civil War—Rice wove a mesmerizing tale of love affairs and family intrigues into the historical setting of the 1840s. “Feast ” incorporated her penchant for psychologically complex characters and used her intimate knowledge of Louisiana lore.

If the literary world had been stunned by Rice’s philosophical meditations on vampires, it was flabbergasted by her third novel, “Cry to Heaven” (1982). Set in 18th century Venice, it is a dreamlike tale of love and treachery among the castrati, the boys who were castrated to preserve the purity of their soprano voices. The bizarre settings, androgynous characters and explicit scenes of diverse sexual activities shocked many readers—but only presaged what would be an even more amazing turn in Rice’s literary career.

In a move that might have appeared suicidal for a successfully published literary author, Rice decided to write a series of explicitly erotic books—what she straightforwardly calls her “pornography.” In the first work of this trilogy, “The Claiming of Sleeping Beauty,” the Prince awakens Beauty both literally and sexually in a sadomasochistic fantasy version of the fairy tale. Her editor at Knopf refused to publish the books, and they were sold to another house, E. P. Dutton, where they appeared under the pseudonym of A. N. Roquelaure. (A roquelaure is a type of French cloak worn in the 18th century.) Despite the pseudonym, Rice has always happily admitted that she is the author of the Beauty books. In fact, in their paperback editions, her real name is the largest type on the cover.

In addition to the two other books in the Beauty trilogy- “Beauty’s Punishment” and “Beauty’s Release”- Rice wrote another pornographic novel with a contemporary selling. “Exile to Eden,” published under the pseudonym Anne Rampling, concerns the love affair that develops between a man and a woman at an unusual sex club on a Caribbean island.

Almost a decade after “Interview with the Vampire,” Rice returned to the character of Lestat. In “The Vampire Lestat,” he is awakened in 1985 by a rock band and becomes a singer. Rice had based part of Lestat’s style and voice on the Doors’ Jim Morrison. The concept of the vampire as a contemporary rock star and the fascinating story of Lestat’s early life made it an immediate best-seller.

Rice then went back to an erotic theme she had toyed with for years. In “Belinda,” she wrote her own version of “Lolita.” The novel was largely ignored in hardcover and was packaged in a romance format in paperback under the Rampling name, but it remains Rice’s best written and least appreciated book.

Another vampire book, “The Queen of the Damned,” the third in the series, further enhanced Rice’s reputation as a brilliant literary stylist. In it, borrowing freely from Christian, Greek and Egyptian mythology, she develops a tapestry of vampire mythology that reaches back 6000 years to explain Lestat’s origins. What readers can hardly help noticing in the third vampire volume is the marked increase in sensuality and violence from her previous books. It is almost as if Rice had moved to a new level of intensity in “The Queen of the Damned.” As the characters whirl around the world in an apocalyptic frenzy of mass killings, the intimate encounters among vampires- and between vampires and humans- become more sensual. The giving of the dark gift of immortality is as erotically riveting as any scene in Rice’s pornography. The brutality of the embrace, the penetration of vampire teeth, the sucking of hot blood, the passionate moment of transformation—this is sexy stuff indeed.

Rice made some important changes in her personal life, too. After spending some time in her second home in the city, Rice and her family moved back permanently to New Orleans in 1988 and took up residence in a large historic mansion (reputed to be haunted) in the Garden District. Her husband, Stan, retired as chairman of the creative writing program at San Francisco State and devoted his time to painting and writing poetry. Their son, Christopher, 15, attends the nearby private school. Anne Rice is cochair of the New Orleans Preservation Society and has recently purchased an 1880 mansion (also supposedly haunted) on St. Charles Street for renovation. The annual Coven Party of the Vampire Lestat Fan Club was held there last year.

The move altered neither Rice’s productivity nor her penchant for variety. In “The Mummy, or Ramses the Damned,” Rice switched to a playful, campy tone. And “The Witching Hour” is a more subdued, intellectual exploration of the supernatural set in Rice’s house in New Orleans.

“The Tale of the Body Thief,” the fourth and Latest volume of “The Vampire Chronicles” (and her lucky 13th novel), takes place in contemporary settings such as Miami, Georgetown and aboard the Queen Elizabeth II. In this story, Lestat is given the opportunity to give up his immortality and return to a human form. Naturally, he chooses to remain a vampire. We wouldn’t want it any other way. How else could we continue to read about his adventures in volume five, which Rice promises to provide shortly?

To learn more about Anne Rice and her world of ghosts and vampires, we dispatched PLAYBOY’s book columnist, Digby Diehl, to New Orleans, where by day he visited with Rice in her home and by night searched for Lestat on Bourbon Street. Diehl’s report:

“When I spoke with Anne on the telephone prior to our meetings, she was terse and businesslike. There were no restrictions on what we would talk about. But she made clear that she would only be available for four hours each afternoon for four consecutive days. No lunch, no cocktails, no socializing As she promised, our talks were interrupted only for periodic refillings of diet Coke and the afternoon arrivals of her son from school.

“What surprised me a bit more each day was not only Anne’s energy but her subtle chameleon ability to shift intonation and delivery as the conversation changed. Anecdotes about her youth were told with a charming sparkle. Ghost tales were offered in a spooky, slightly lowered voice, and denunciations of censorship came booming out angrily.

“What surprised me a bit more each day was not only Anne’s energy but her subtle chameleon ability to shift intonation and delivery as the conversation changed. Anecdotes about her youth were told with a charming sparkle. Ghost tales were offered in a spooky, slightly lowered voice, and denunciations of censorship came booming out angrily.

“In the end, I realized that her initial formality was a way of protecting herself from her own warm nature. There is an openness, a generosity of spirit about her that would make it easy for a visitor to impose upon. It is better she should set limits and save time to spend at her word processor “

* * *

PLAYBOY: You are a feminist and yet you have written explicit sexual fantasies. How do you reconcile those two things?

RICE: I believe absolutely in the right of women to fantasize what they want to fantasize, to read what they want to read. I would go to the Supreme Court to fight for the right of a little woman in a trailer park to read pornography—write it, if she wants to. I think one of the worst turns feminism took was its puritanical turn, where it tried to tell women what was politically correct sexually. I mean, we had that for thousands of years. I got that from the nuns at school: what you were supposed to feel as a temple of the Holy Ghost, what you were supposed to allow. And to hear the feminists then telling me that having masochistic fantasies or rape fantasies just isn’t politically correct, I just thought, Oh, bullshit. You’re not going to come in and politicize my imagination.

PLAYBOY: Not all feminists agree with you. The Los Angeles chapter of the National Organization for Women called for a boycott of most Random House books because it published Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho, which featured the murder and mutilation of men and women.

RICE: I was outraged by the boycott. If Random House doesn’t have the right to publish a disgusting book, then young editors all over New York will never get radical books through their publishing houses. Those women are treating Random House as if it were a great big, monolithic publishing house. It’s not. Publishing has always been made up of courageous individual editors fighting for individual books. I was furious. I hate censorship. I hate it in any form. Can’t those people see that if they could win that battle and force the book not to be published, other interest groups could then force all kinds of other books not to be published? I was just horrified. I would have defended Random House with a wooden sword in front of the building.

PLAYBOY: Have you had problems with censorship of your own books?

RICE: Not really very much. Knopf didn’t want to publish my pornography, but that was the individual decision of my editor, Vicky Wilson. She read the first book and said, “I can’t publish this.” But she recommended Bill Whitehead at Dutton, who published it. So I stayed at Knopf as Anne Rice and went off to Dutton and wrote the A. N. Roquelaure books. Vicky really is a dedicated editor, but she can’t publish something she doesn’t understand. She really just didn’t get it. It is pornography. She said, “If I were to publish this, all the sex slaves would have to fight to be free and to escape. ” I just said, “Oh Vicky, I don’t want to do that. This is a sex fantasy about being a slave. They don’t want to get away.”

PLAYBOY: Why did you decide to write explicit erotic fiction ?

RICE: First of all, I think the masochistic fantasies explored in my pornography, and rape fantasies in general, are fascinating things. They have to do with our deep psyche and they transcend gender. Both men and women have these fantasies. And to pretend that they don’t exist is ridiculous. I don’t believe the old argument that people read pornography and go out and commit crimes. The vast majority of crimes are committed by people who aren’t reading anything. They don’t need Beauty’s Punishment to go attack some old woman in Oakland, steal her welfare check and rape her. It doesn’t work like that. I’m fascinated by sadomasochism. I’m fascinated by the way that the fantasies recur all over, in all kinds of people from all kinds of lives. I’m not particularly interested in the people who act them out. I have nothing against them, and I’ve found them interesting when I’ve run into them. They come to my book signings sometimes and say, “Do you want to come to our demonstration of how to tie all the knots ?”

PLAYBOY: They invite you to bondage demonstrations?

RICE: Yes. There are groups in northern California that believe in healthy, safe-sex S&M. They’ll give a lecture on how to tie up your lover but make the knots so that you can get them undone quickly. Or if you’re going to use locks and chains on your lover, to be sure that all the locks use the same key, so that you can unlock them quickly. An organization up there invited me to their demonstrations. One night they had a dungeon tour: They were going to visit this one’s dungeon and that one’s dungeon, this one’s torture chamber and that one’s room. The organization was mainly made up, as I recall, of people who just liked to practice S&M. There were married couples in it, there were a lot of lesbians in it and there were a lot of professional women. The women did this professionally, largely for male customers. They were very hygienic.

PLAYBOY: What do you mean by “professionally” ?

RICE: They charge money. Dominatrixes. What fascinated me about them was that there were no males who did it to women for money. If you wanted to go to San Francisco and say, “I would like to be dominated by a pirate for sixty minutes in a completely safe atmosphere where he’ll just take over but never get really rough,” you can’t do it. But men do it all the time. They go in and get dominated for an hour in a safe context. It’s amazing to me. So my books are for the women who can’t get that.

PLAYBOY: Did you go on the dungeon tour?

RICE: No, I didn’t go. I’m shy. I did go to the house of one of the people, and I did see all of the whips and the chains that she had. The little phalluses and everything. She was dedicated. This was a gay activist who wrote all the time for gay publications. She’s very much an S&M dyke, I believe she would call herself. She showed me all of these beautiful leather handcuffs and stuff that she had made, this entire lovely armoire filled with them. And a drawer filled with all these little dildos and things. I was fascinated, but that was enough. I mean, I really am a retiring person. I don’t show up dressed in black leather as Madame Roquelaure. I’m not a dominatrix. I have almost no interest in acting it out. That was never what mattered to me. It was the fantasy, and I have discovered how many of us share that fantasy. Over the years, because of those books, I’ve run into thousands of people. Now those books are in the suburbs. They’re everywhere, and women come up with babies in strollers and say, “We love your dirty books. Are you going to write some more Roquelaure?” They put it right in the stroller with the kid, at the bookstore. I think that’s great.

PLAYBOY: What is the answer to their question: Will you write any more explicitly erotic books?

RICE: No, I don’t think I will. I wanted to write some top-notch pornography in the genre, material that was just pornography. Where every page was a kick. I think I did it, and it would just be repetitious to write more. Also, I have to confess, since I’ve grown older and I’ve lost more friends from AIDS, and just experienced more of life, my vision has darkened a bit. I’m not sure I could put myself in the happy-go-lucky frame of mind I was in when I wrote the Beauty books. But I’m glad I wrote them. I’m proud.

PLAYBOY: You’re clearly not in sympathy with Catharine MacKinnon or Andrea Dworkin, who have proposed recent antipornography legislation.

RICE: I think they’re absolute fools. If two Baptist ministers from Oklahoma came up with their arguments, they would have been immediately laughed out of the public arena. They got away with their nonsensical arguments because they were feminists, and because they confused well-meaning liberals everywhere. But the idea that you can blame a piece of writing or a picture or a film or a magazine for inciting you to rape a woman is absolutely absurd. If you give the woman the right to sue and say that a magazine was the cause of the rape, there’s only one step from that for the man to say,

“Yes, it was the magazine that made me do it, and it was also the way she was dressed.” Why can’t he sue her?

PLAYBOY: And her dress designer.

RICE: Good point, Her dress designer and the guy who ran the bar. That MacKinnon and Dworkin don’t see this drives me crazy. I think that is the most evil piece of legislation I have ever heard of. We’ve spent all this time trying to get men to take responsibility for rape. When I was a kid in the Fifties, we knew that half of the time the police blamed the victim. Women didn’t want to report it. OK, we’ve reached a time when we’re urging women to report the crime. The man is responsible if he does it. He can’t blame it on the woman, he can’t say she asked for it, he can’t say she shouldn’t have been in that bar, or that she shouldn’t have gone to his apartment.

And those two MacKinnon and Dworkin, in their madness, want to take that responsibility off the man again and put it on PLAYBOY, or whatever he was reading. That’s bullshit! It’s not true. We know statistically that pornography does not incite people to commit crimes.

PLAYBOY: Don’t women need special protection in some cases?

RICE: Two things have gone side by side throughout the feminist movement: a protectionist idea that women are victims and have to be protected, and the belief that women are equal and have to have equal rights and equal access to everything. The two really clash on this issue. I don’t believe women are victims who have to be protected from everything. I believe when someone is a victim of a crime, that person is entitled to protection of the law and the courts. But I don’t think that women per se are so gullible or foolish that they have to be protected by legislation like that. These people think that if a woman can be made to have sex with a donkey, like for an erotic film, she can be made to sign a contract. The fact that she signed a contract doesn’t necessarily mean that she wasn’t a victim. That’s absurd. If they can’t be trusted to sign a valid contract because they’re women, then women shouldn’t drive, they shouldn’t vote, they shouldn’t hold jobs.

PLAYBOY: Rape is another issue, isn’t it?

RICE: I think this is a crisis time with regard to rape. I don’t think there’s ever been a time when women have been so vulnerable to rape and there’s been such an outcry against it. As a student of Western civilization and law, I’m fascinated by what’s going to happen with the notion that when she says no-no matter when it is- it’s over. I think it’s important to women’s freedom, and important to our dignity and our rights as human beings, that rape be a crime, that nobody has a right to force himself on you, whatever you are.

PLAYBOY: Have you been following some of the public rape trials ?

RICE: I didn’t think there was sufficient proof in the William Kennedy Smith case to bring an indictment. I thought a real injustice was done to that woman when she was taken that far by the legal system.

PLAYBOY: What is your reaction to Mike Tyson rape case?

RICE: Again, you have to extend the protection of the law even to a girl who’s stupid enough to go to Mike Tyson’s bedroom at two o’clock in the morning. She has the full protection of the law. She may be an idiot, and she may be doing something that none of us would have done when we were her age—we would have had more brains! If Mike Tyson had said, “Come up to my hotel room” to me, I would have said no.

PLAYBOY: Do you think you would have known what to expect?

RICE: From what I could tell, what happened in that case was that she did expect something to happen, but she expected it to be romantic and she expected it to be nice. And what she got was unpleasant and nasty. And she was entitled to the protection of the law against that. You cannot invite someone to your house for a party and then beat them up and say, “Well, you accepted my invitation, and that was the nature of the party: It was a beating-up party. ” That’s what I suspect happened, but I really don’t know. I think she was prepared for sex and consummation, but wasn’t prepared to be mauled or bullied or hurt. I think she felt outraged afterward, and she had the courage to say that shouldn’t happen to someone. That is really what rape is.

PLAYBOY: Are we always stuck with the he-said-she-said problem?

RICE: I think we have to fight each one out. We have to guarantee women this protection. You cannot tell women that the price of equality is that they might get raped. I think that as a culture we’re desensitized to how awful rape is. We see it played with so much, and we see it on television in so many forms all the time, that it is hard for us to imagine what an outrage it is when someone has to force himself on a person that way. I think the movie that brought it home to me most honestly was Thelma & Louise. I would have shot the guy immediately. If he had done that to my friend, I would have blown his head off. That was so outrageous a violation of that woman’s privacy and dignity that I didn’t see why Louise waited. I praise that movie because I think it showed how awful rape is. And it’s hard to show it without its being sexy because it is sexy. And rape fantasies are part of our brain. They’re part of our genetic heritage, and that’s not going to go away if you ban pornography. It’s an archetypal fantasy.

PLAYBOY: What about the argument that sexual images in movies and TV affect public consciousness?

RICE: When you’re talking about the content of programs, I’m leery of anybody trying to turn the media into propaganda. I feel that we need a creative jungle out there, that we have to put up with some people who use the First Amendment and use free speech in a way we find repulsive. And it’s worth it for the price of free speech. Also, I feel that there are certain people whose function is to outrage us. Madonna, to me, is wonderful. She would be the one person to whom I would sell video or film rights to the Beauty’ books. Of course, she has not knocked on my door asking for them, but I would not consider anyone else. I think what she’s done in those videos is so courageous, the way she’s played with those fantasies and those images. The idea that somebody tried to censor her or keep one of those things off TV is outrageous. We ought to know that those people are going to stretch limits and are going to say outrageous things.

PLAYBOY: How do you feel about the extreme case of child pornography?

RICE: I think the crime there is the making of the pornography, the using of a child to commit a crime. And if what your watching is a record of the crime, an act that’s involved with the commission of that crime, I can see laws against that. A child has certain protections until he or she is eighteen. But you prosecute people for exploiting children. You don’t persecute on the content of the film. I am really pro-freedom. Freedom means that somebody is going to abuse it or use in a way you don’t like. It’s not freedom if they don’t do that.

PLAYBOY: Do you think pornography has any effect?

RICE: It’s almost a superstitious reaction to think that people are going to act out pornography. We know, for example, that thousands of people read Agatha Christie mysteries. They don’t try to become Miss Marple. They read Mickey Spillane and they don’t shoot one another. The readers of Louis L’Amour do not carry six-guns and tobacco pouches everywhere they go. So to think that for some reason the readers of erotic fiction are going to be different, that they’re going to jump right up and act out everything in the book, is absurd. It doesn’t work that way. They’re taking a mental trip with that book, just like the readers of Agatha Christie. And good pornography does what good mystery fiction does or good Western fiction or good science fiction: It takes you to another place. It allows you to enjoy that place for a little while, and then you come back. If it’s really good, you know something you didn’t before you went.

PLAYBOY: On what kind of mental trip are you taking the readers of The Vampire Chronicles?

RICE: What interests me about vampires are their mythic qualities. They’re characters in our literature, and they’re great. But I have never met anyone who was a real vampire. I do believe in a lot of the rest of the occult. I think that there probably are ghosts. There’s an abundant amount of proof that there are some sorts of apparitions and spirits and things like that. But a vampire, I think is strictly a mythic character, almost out of ancient religion. It’s like writing about angels or devils. There’s a great deal of meaning there. Whether you believe people have ever really seen an angel or a devil isn’t the point. What I have done is to take a B -movie image and say that it is as significant as a magical character in the Renaissance and treat it that way. Because the book is a special world—with language, thoughts, ideas, concepts and characters you are drawn into—you forgive the fact that it’s basically absurd.

PLAYBOY: Speaking of the B -movie image, will we ever see The Vampire Chronicles on the screen?

RICE: Interview was sold to Paramount in 1976. Richard Sylbert, who was the head of the studio at the time, really wanted to make it. Before the contract was even signed, he left Paramount. Michael Eisner and Barry Diller came in. Then John Travolta came in and made some sort of deal with Paramount. His managers were interested in his doing Interview with the Vampire. They took it as part of a package with Paramount, and they took control of that property for a long time. The truth was, Travolta didn’t want to do it, so it never got made. Years passed, and more and more was charged to the picture—scripts and so forth—until finally, I think, it had a debt against it of six or seven hundred thousand dollars. They dumped it on the television division about 1984. A television producer then began to develop a script for it. In the meantime, I’d written The Vampire Lestat. Because of the sequel rights in my original contract, I had the right to sell the movie rights to Lestat if Paramount didn’t want them. They didn’t. So other people became very interested in developing The Vampire Lestat. Julia Phillips, the producer, was particularly interested.

PLAYBOY: Thus you came to play a role in her book, You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again.

RICE: Isn’t that wild? Julia and I are very different. I wish she had not hurt so many people’s feelings. But I do think she’s a talented writer. Anyway, she did come into my life being interested in The Vampire Lestat because she couldn’t get Interview away from Paramount. She pitched it to the studios and really started it off on a life of its own. Meanwhile, Interview reverted back to me. Julia and I tried to get the properties united with one company. For awhile, Julia had a brilliant idea to develop The Vampire Lestat as a movie while she did Interview on Broadway as an opera or a musical. At that point she began to talk to David Geffen about it. David was kind enough to give me a shot at writing the script, and I submitted a revised version to him. But who knows? Right now, Interview is still in development.

PLAYBOY: So The Witching Hour will probably be the first of your books to make it to the screen?

RICE: It’s supposed to start shooting soon. But The Witching Hour is easy compared to The Vampire Chronicles. It’s mostly humans.

PLAYBOY: And they’re going to shoot it in New Orleans ?

RICE: They have told the mayor’s office that they want to shoot some of the movie in New Orleans. It’s exciting. It’s never been this close before, it’s always been just at the script stage.

PLAYBOY: Do you like dealing with Hollywood?

RICE: I went there a lot at Julia Phillips’ behest. Julia dragged me down there enough times that I lost my fear of those people. I sat at so many dinners at Morton’s with Julia, meeting Adrian Lyne and Mel Gibson and blah-blah-blah that she really defused that world for me. I realized that these were, in fact, often limited people who had jobs only for short periods of time.

PLAYBOY: What insight did you gain about how to deal with Hollywood?

RICE: My primary insight is don’t eat lunch in that town, except with David Geffen. He can make your project a reality. Just don’t eat your heart out for somebody who comes back and whines, “I couldn’t get them to read it.”

PLAYBOY: In your life as a novelist—

RICE: My real life!

PLAYBOY: You’ve written a breakthrough book. In The Tale of the Body Thief, the vampire Lestat finally has the opportunity to be human again.

RICE: A good opportunity. A good shot at it.

PLAYBOY: But he chooses to remain a vampire.

RICE: I always thought that’s exactly what would happen, but I was ready to let the book go in whichever direction it wanted to go. I felt he had to confront the fact that he really loved being what he was. The fourth volume in The Vampire Chronicles is really about the ruthlessness, the evil, in us all. You and I are sitting here, and we know right now people are dying horribly in Iraq or in Ethiopia. But we choose to sit here. We’ve made that choice. We’re not going to spend our lives trying to save one village in India. That’s what that book is about. Lestat chooses to remain a powerful, immortal being. And I think most people would make that choice.

PLAYBOY: The minute Lestat gets out of his vampire self and into a human body in The Tale of the Body Thief, he has exclusively heterosexual encounters—and unhappy ones at that. Some readers identify vampires with gay sexuality. Isn’t this going to fuel that stereotype?

RICE: Well, probably. I really see the vampires as transcending gender. If you make them absolutely straight or gay, you limit the material. They can he either one. They have a polymorphous sexuality. They see everything as beautiful. To them, it no longer matters whether the victim is a woman or a man. And I do see Lestat as a real 18th century bisexual. Either the village girls or the village boys, depending on who’s around. It was really a middle-class idea that came in with the revolution that homosexuality was a perversion.

PLAYBOY: How do women readers react to The Vampire Chronicles androgyny?

RICE: I would say that there is certainly a kind of woman who finds two men together very attractive, and I have a lot of those readers. But, by and large, most of the women I’ve known are afraid of homosexual men. We have deep-rooted fears when we see people of the same sex kissing and embracing, no matter how sophisticated we are. There can be a genetic rush of fear. The species is threatened. I have to remind myself of what that’s about, because I don’t feel it. I’ve always rather romanticized gay people as outsiders bravely fighting for sexual freedom and being willing to take the slings and arrow’s from the middle class. Certainly Lestat is an outsider, an immortal who is offered the choice and chooses to remain a vampire.

PLAYBOY: Critics have pointed out that The Body Thief is a real departure from the other Vampire books.

RICE: To me, The Body Thief was the first modern Chronicle in that the exploration was inner, psychological. All the other Chronicles were really devoted to going back and finding the answers in the past—reading history, finding secrets, crashing into sanctums and discovering truths, and encountering over and over again the statement: “History doesn’t really help.” You always wind up back where you started. I like it very much, going in this other way, the psychological way. If I hadn’t been pleased with this book, I would have thrown it away.

PLAYBOY: Have you thrown away books before?

RICE: Just before taking up The Body Thief, I wanted to do this book, In the Frankenstein Tradition [In italics in original, EF], about an artificial man. For some reason, that has just not come together. I don’t know why. I went back and read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and was terribly excited about it. What an incredible book. What a brain she had at nineteen! I just loved it. I really wanted to do something with those concepts, and I began to see that I couldn’t do what I wanted to do.

PLAYBOY: Like Mary Shelley, you’ve absorbed a lot of things that are out there—ideas, things that people are thinking about and feeling. They’re not necessarily expressed in a direct way, but they’re addressed by your characters and their concerns.

RICE: I always felt that any book that’s going to be really good is about everything you know or everything that’s on your mind. At least for me that’s the way it always works. In the beginning, when I first started having books published, one of the distressing things was to watch critics view them as historical novels and not see that they had to do with the present moment. But American fiction is so influenced by the idea that to be profound a book has to be about the middle class and about some specific domestic problem of the middle class, that it’s hard to make your own path. You’re really working against that. Unless you’re a South American surrealist, you have a hard time.

PLAYBOY: Why do you write serious books about such strange stuff?

RICE: I came of age in the Sixties in California, and the prejudice was that a really profound book dealt with one’s own recent experience hitchhiking in Big Sur. Somebody writing books like I wrote was writing trash, basically, according to the conventional wisdom. I sort of had to fight against that because I didn’t know any other way to write. I recently have been reading books about what art was like before the Reformation. And what became very clear to me was that the novel today—John Updike, Anne Tyler, Alice Adams-is really the triumph of Protestantism. It’s a Protestant novel. It’s about real people. People who work, usually, and who have small problems. It’s about their interior changes and their moments of illumination. And that is the essence of what Protestantism come to be in America. Out with the stained-glass window’s, out with the saints, out with the chants and the Latin and the incense. Out with Faust and the Devil. It’s you, your Bible and God. Those novels are personal. They affirm the Protestant vision that everything is sort of an interior decision to make– as you make a good living and as you fit into the community in which you live.

PLAYBOY: Were you aware of feeling separate from the cultural mainstream early in your career?

RICE: Having grown up in New Orleans—the only Catholic city in America—amid all this decadence, I grew up with a completely different feeling. I was nourished on those stories of the saints and miracles and so forth. I really thought it was fine to write a book in which everybody was a vampire and they all talked about good and evil. The industrial revolution and Protestantism came together in America in a way it didn’t in any other country in the world, with such force and power. To see our literature finally dominated by things that used to be Saturday Evening Post short stories is really the final triumph of the Protestant vision in art. It’s basically a vision that says if it’s about God and the Devil, it has to be junk. It’s science fiction; it’s dismissible.

PLAYBOY: Do you mean all fantasy is Catholic?

RICE: If you think back to before Martin Luther about what literature was, the spiritual exercises of Saint Ignatius encouraged you to use your imagination. You’d sit there and close your eyes and think about what Christ felt like as they drove the nails through his hands. See, I grew up on that. We did those exercises. That was an approach to imagination that was entirely natural to me. All that came to an end with Protestantism. Protestantism put its faith in the less magical, more practical, more down-to-earth and—in this country, ultimately—the more sterile. But I see that now. I love living here, and this really is a Catholic city in the sense that it doesn’t fix its potholes.

PLAYBOY: Are potholes Catholic, too?

RICE: They’re Catholic because people really don’t care that much about progress or cleaning up. Think about it. Go to Venice or go to Mexico. Think of the countries that are Catholic. Think of the people who came to America who have been gangsters. They’ve almost all been Catholics-Italians, Irish. You don’t hear a lot about German gangsters or Swiss gangsters or Dutch gangsters—except for Dutch Schultz. Catholics still live in a world that’s filled with dash and flair and color and drama and terrible injustice. There’s a sort of acceptance of things. This city moves at its own pace. People here are natural storytellers. They really are spiritual, in a Catholic sense. They really do care more about a good cup of coffee than mowing the grass. In a city like Dallas it’s much more important to mow your grass. The cup of coffee comes next. In San Francisco it’s more important to go to work, get a job, sweep the pavement. And that’s wonderful. I’m glad we live in a Protestant country. I’m talking about this strictly in terms of cultural movements.

PLAYBOY: Do people in New Orleans have a different vision of reality?

RICE: I have met countless people in New Orleans who have told me their personal experiences of seeing ghosts. I never met these people in California. Not in thirty years have I ever met anyone in New York or California who claimed to have seen a ghost. And since I’ve been here, people look me right in the eye and describe the ghost’s clothes and what it did as it came up the stairs. They tell me absolutely I should come to their house and see this ghost, that it really is there. I’m amazed!

PLAYBOY: When did you break away from the church?

RICE: I didn’t know anything about the modern world when I lived in New Orleans. I never read a line of Hemingway until I was twenty. I didn’t even know such people existed. I grew up in such a closed, Catholic environment that when I moved to Texas and went to college and discovered things like existentialism, it was like emerging into the modern world. I thought, I have to know what’s out there. I have to read Walter Kaufmann’s books on existentialism. I have to see who Jean Paul Sartre is. But I wasn’t supposed to read all this. It was a mortal sin if I read it. That’s when I broke with the church. It was astonishing. I’m thinking about this a lot lately. I guess now that I’ve come home, thirty years later, I see a lot of it in perspective I didn’t before. I was sort of battling these voices and demons and different things, trying to figure out things. Why did everything work for me when I introduced a character who is a vampire? Why did I suddenly start to be able to write about everything I felt when, for other people, the opposite was true? I don’t know, but I see it now, and I do think it’s this battle of the Protestant and the Catholic.

PLAYBOY: Where would a writer such as Stephen King fit into your cultural division of Catholic and Protestant visions?

RICE: I read all of Stephen King’s early books I have not caught up with his output because I’m a slow reader. But I think Stephen King is a very fine writer, and I learned a lot from Salem’s Lot and from Firestarter. He’s the master of talking about ordinary people in ordinary situations and them confronting them with the supernatural or the horrible. That’s American and Protestant to take horror and put it in that context. He did a kind of genius thing. He created a proletarian horror genre. He departed from the European tradition of spooky houses and doomed aristocrats, and he created this wonderful world of horror in middle-class America. It’s brilliant!

PLAYBOY: We’ve never heard anyone describe Stephen King quite that way.

RICE: He is absolutely a brilliant, Protestant, middle-class American writer. He’s really great at that. But there was one point when I was reading the reissue of The Stand—I was into it and I loved the writing—and I thought, No one has survived this flu who is really an interesting person. They’re all these wonderful Stephen King people, but I would really like some truly heroic person. Heroism to me is real. People can be heroic. And what interests me in fiction is creating those exceptional people—Lestat, Ramses—people, as I’ve said, who are bigger than the book. King doesn’t do that.

PLAYBOY: In Stephen King’s books and in your own books there is a lot of violence. How do you feel about that?

RICE: I love it. It’s obvious, isn’t it?

PLAYBOY: Many people would find your reaction troubling.

RICE: I don’t think we can have great art in our society without violence. Everything is how you do it: the context. Prime-time TV really hurts kids because again and again it presents mindless, senseless, motivationless, sadistic people hurting one another. It’s horrible. Crimes committed by sneering, tough-job, nasty, snarling criminals. We don’t know where they came from or why they’re the way they are. Prime time presents them in all these cop shows as the reality of the streets. I think that’s been terrible for our morale. But I think when you take a movie like Scarface, written by Oliver Stone and directed by Brian De Palma, you have a symphony of violence that’s a real masterpiece. It has a beginning, an end, a middle and a moral: the rise and fall of Tony Montana, the cocaine dealer. I love that movie and I watch it over and over again. I wanted to dedicate The Body Thief to Tony Montana, but I didn’t have the guts. And, by the way, I once had an opportunity to meet Oliver Stone, and I said just what I said to you, that I love violence, and he said, “So do I.” We laughed. I think he was being honest.

PLAYBOY: Are the people who oppose violence less than honest?

RICE: We Americans are such hypocrites about violence. Maybe there are a few Americans out there who really never watch anything with violence in it. But ask them if they’ve watched Gone With the Wind. Everything depends on context. To me, the context has to be really strong. The moral tone of a work is important, the depth of the psychology is important, the lessons, the feeling afterward of moral exhilaration as well as of having been entertained. All that is very important about a work of art. But I would be lying if I said I didn’t enjoy violence in a strong context, because the best of our art contains violence. Moby Dick is violent, don’t you think? If we cleanse all the violence out of our work, we will really have the Saturday Evening Post short story triumphant. That will be our art. We’ve gone through phases where we’ve nearly done that, and it’s pretty dismal stuff. But I do love violence, I absolutely love it. I loved The Godfather. I remember people coming home and saying it was too violent, the horse’s head, oh my God. I thought it was great. I thought it was a masterful use of violence. That’s my field and I love it.

PLAYBOY: You’re also a big boxing fan, aren’t you?

RICE: Yeah. We had a writer friend, Floyd Salas, who introduced Stan and me to boxing. We got into it and would go with him to the Golden Gloves in San Francisco every year. But the amateur matches in Oakland and Richmond with kids sponsored by the police were really a trip, I’ll never forget how sensuous the Oakland Auditorium was. The auditorium is vast, much larger than the crowd. We would get in that audience surrounding the ring, down in the middle of the auditorium. Those two beautiful spotlights would hit it, and out would come these gorgeous bodies and they would start hitting each other. I thought it was terrific. I really developed a love for boxing then that I’ve never lost.

PLAYBOY: Didn’t Salas get you to put on the gloves once?

RICE: Floyd was always helping the boxing team at Cal, and one time I got in the ring with him. I found it a bit too rough, I mean, one blow to the head, even with that mask, is enough. It was a bit too rough, but it was fun. I don’t have—well, I do have a killer instinct, I guess. No, I really don’t. I think that it was great fun to pretend, until somebody—me—got hurt for a second.

PLAYBOY: Fighters get hurt all the time.

RICE: I remember one awful moment at the Golden Gloves. The place was packed and I was just coming back into the auditorium with a hot dog or something, Two guys were in the ring, one of whom was a medical student. Just as I entered the auditorium, the medical student had been almost knocked out, and he had dropped to his knees. He was clearly dazed—he didn’t know what he was doing. At that moment, the whole crowd stood and began to roar. There was something horrible about that moment of seeing that kid. There he was, obviously badly hurt, and that whole crowd was roaring because this is exactly what they had come to see. I realized that we were screaming as much to see these guys go down as to go up. I hadn’t quite thought about it that way. I had thought of it as screaming more for the guy who scored a punch, for his triumph over something. Yet here’s this med student who really should be protecting his brain, and he’s on his knees, dazed, in front of all these people who are screaming as if they were in a Roman arena.

PLAYBOY: Now that you have moved back to New Orleans, do you see yourself more as a Southern Writer?

RICE: I was always a Southern writer. It was good to come home and acknowledge that. Books that I have cherished and loved are books like Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Reading over and over again the language in that book and loving it. Eudora Welty’s short stories, I just pick them up and read words. I don’t even have to know what the plot of the story is—if she happens to have one. Sometimes she doesn’t. She has a great story about two people who meet in New Orleans and drive south along the river, down the road. I believe that’s all that happens in the story. They drive and become almost narcotized by the landscape. Then they go back to New Orleans and they part. I love that story. I feel like my writing has always been very much influenced by these lush Southern writers.

PLAYBOY: There is something about a lot of your material-dealing with the supernatural and time travel—that’s fundamentally anti-intellectual. But you’re an intellectual. Isn’t that a contradiction?

RICE: Well, it’s that Protestant-Catholic thing again. I’m a serious intellectual, and I certainly was a serious spiritual person who wanted to be a great writer. I had Carson McCullers and Hemingway and Dickens and Stendahl stacked on my desk, but I couldn’t find my way in contemporary literature until I hit the supernatural and its advantages. And then I took everything I had to give and put it in there. That’s always been the contradiction of my work.

PLAYBOY: What did you read as a child?

RICE: The Lives of the Saints, that’s what I read as a kid. Soap operas, yes, they made a big difference. And radio made a big difference. I’m increasingly realizing how much radio was an influence—Lux Radio Theater, Suspense, Lamont Cranston. I had forgotten. But playing tapes of old radio shows, I’m really beginning to realize how much my work sounds like a radio show. It really does, to a large extent.

PLAYBOY: How did you come up with the idea of doing Interview with the Vampire?

RICE: It was haphazard. I was sitting at the typewriter and I thought, What would it be like to interview a vampire? And I started writing. I was very much a think-at-the-typewriter writer then, more so than now. I would start with a blank page and have no idea what I was going to do that night, except that I was going to write for several hours. And I just started the idea of this boy having a vampire in the room, and the vampire wanting to tell the truth about what it was all about. The vampire explained all about drinking blood and absorbing the life of the victim, that it was sort of a sacramental thing. He talked about being immortal and so forth and so on. I took that story out several times over the years and rewrote it. It was at one of those points when I was rewriting it, to include in some short stories that I hoped to enter into a contest at Iowa, that it took off and became the novel. And, of course, I had encouragement from friends. Friends had said, “I think you really have something with that story; that story is so unusual.” I really began to let it go, and something like five weeks later, the novel was finished. I had forgotten the contest. I never finished the short stories. They all went back in the drawer.

PLAYBOY: You really wrote most of that novel in five weeks?

RICE: Yes, but that was the period when my daughter had just died, and I wasn’t doing anything except drinking and writing—often all night long.

PLAYBOY: That must have been a terrible time.

RICE: I was just a drunk, hysterical person with no job, no identity, no nothing. There was a two-year period after her death when I just drank a lot and wrote a lot, like crazy. Then I sort of came out of it and wrote Interview with the Vampire. My husband had told me, “I really believe in your writing.” He was working at San Francisco State. He wasn’t chairman yet, but he was a creative writing professor with tenure there. He was the breadwinner. I went out and got a job for a while and was miserable. He said, “Quit the job. I believe in you and I believe in your writing. We have my pay, so just write.” I’ve always felt that that was one of the greatest things he ever did for me, other than being his wonderful self.

PLAYBOY: Do you think that in some ways the shock of your daughter’s death shaped your literary vision?

RICE: No doubt about it. It had a devastating effect. There’s a period after a death like that when you don’t think the lights will ever go back on. I mean, you don’t like doing anything—vacuuming the floor or cooking a meal or walking out of the house. I remember even in the immediate weeks after her death it was hard for me to swallow’ food. I felt a disgust for everything physical. I kept thinking of her in the cemetery. And even though I don’t believe she’s in that body, I couldn’t get it off my mind. That went on for a long time, as a matter of fact. Particularly late at night. Until very recently, I’ve had thoughts about the fear of death and thoughts of her. In fact, only on the return to New Orleans would I say I let go of that. I felt that I could perhaps have her in another way. It doesn’t have to be such a painful thing every night. I think we cling to these things because we don’t want to lose the person. It’s a form of fidelity to keep grieving like that.

PLAYBOY: Was the writing of Interview with the Vampire a conscious effort to sublimate your grief?

RICE: An interesting thing to me about Interview, in retrospect, is that I never really connected her with it. I remember the night I told Stan the whole story of Interview. We went over to the Cheshire Cat in Berkeley and we were having some beer. I had been writing the book and I said there was this little girl vampire in it and she’s four years old, and Stan said, “Oh, no, no, no, not a four-year-old vampire. You can’t have a vampire that young.” I said, “All right, all right, a six-year-old vampire!” But neither of us said, “Michele?” If I had done that I would have been blocked. The character, Claudia, was a little fiend. When I look back on it I think, How in the world could I have been so detached? But I really didn’t think of that as being about my life. I just thought, I’m writing this thing, and for some reason when I work with these comic-book vampire characters, these fantasy characters, I can see reality. I can touch reality. This is a context. My books before that had been uneasy mixtures of contemporary California and the French Quarter and Garden District in New Orleans. People thought I was making up all this stuff about the South. They thought I was getting it out of Dickens or something, Miss Havisham and her big house. So it never worked. But anyway, that is what strikes me as so strange, in retrospect, that I didn’t completely connect it. It’s like I had a dream. The novel was a dream of everything that had gone on, but I didn’t make the connection.

PLAYBOY: And it really was connected with the deeper reality.

RICE: Yeah, I think it’s a novel all about grief and about loss of faith and about being shattered—yet wanting to live, being sensual and wanting to live. And the sensuality of drinking is certainly in there. I don’t like to talk about it because I think it’s a trivial aspect of the book, but it’s about alcoholism. It’s about being drunk. The whole experience of the dark gift is like a drunken swoon. It’s almost a drug experience. It’s like the golden moment of drinking, when everything makes sense. It was a lot of talking about the craving for booze, the need to drink. That wonderful feeling of transcending and everything meaning something when you are drunk, and yet it was crumbling away.

PLAYBOY: You say that it came from your own drinking experiences, but there are people who connected it with drugs.

RICE: Marijuana. I had powerful experiences on marijuana that were so intense that I quit smoking. And I never touched it again. But I had what other people might refer to as psychedelic experiences just smoking grass and drinking beer. I was describing that in Interview. I was describing that entire knowledge, you might say, of listening to Bach when very stoned, so that the music is just lapping and lapping. I had absolutely ghastly experiences of perceiving that we were going to die and that there was no explanation, that we might die without ever knowing what this was all about. And I never recovered. I described it in The Vampire Lestat. He saw death in the golden moment, and that was exactly happened to me.

PLAYBOY: Is the issue of immortality what The Vampire Chronicles are essentially about?

RICE: The Chronicles are about how all of us feel about being outsiders. How we feel that we’re really outsiders in a world where everybody else understands something that we don’t. It’s about our horror of death. It’s about how most of us would probably take that blood and be immortal, even if we had to kill. It’s about being trapped in the flesh when you have a mind that con soar. It’s the human dilemma. What does Yeats say in the poem? “Consume my heart away; sick with desire/ And fastened to a dying animal.” That’s what I feel it’s really true to. People are shaken by those things.

PLAYBOY: For your fans, I understand that there’s a lighter side to the vampire fantasy, too.

RICE: Yeah. I have some readers who go to the dentist and they get these little fangs made that fit on their teeth. They get them fitted by the dentist and made the same color as the rest of their teeth. In fact, I heard that I have a whole gang of fans in Los Angeles who do that. They put on their teeth and go out at night and sit in cafes, show their fangs. They’ve come to my door, the people with the fangs. They come to the coven party. They call me on the telephone. Let me emphasize again: All of these people know this is fiction. We’re talking about people in their thirties and forties. This is fun to them. This is almost a hobby to be part of the fan club, to dress up like a vampire and to love vampire movies. They’re vampire groupies. It represents the romance in their lives. They’re wonderful people. I have never met a single one who’s been a sinister Satan-worshiping person or anything like that. They just exude goodwill and cheerfulness and laughter. Lots of laughter. It’s all fun. Even when they won’t step out of their vampire persona, they’re just pretending to be vampires and they won’t answer questions as anything but a vampire, they’re laughing. It’s all a gag.

PLAYBOY: You said people call. How do they get your number?

RICE: It’s listed, with the address, in the phone book.

PLAYBOY: You’re sure you want to say that in print?

RICE: Yes, that’s fine. It is listed, but only a certain type of person takes the trouble to find your number and call you, so it tends to be very similar people who call. They’re usually young, they’re usually college students and high school students. They’re enthusiastic about the books and they’re nice. They just want to talk for a minute. They just want to say how they enjoyed the books, or they just want to know if there’s another one coming out.

PLAYBOY: What books can we expect after The Body Thief?

RICE: I’ve completed a sequel to The Witching Hour entitled Lasher, which plunges again into the Mayfair family. I’ve kind of resigned myself to the fact that it’s a hybrid science-haunting novel because Lasher is here with us on this side. I’m fascinated by genetics and science and DNA and evolution, so I get into questions of a mutation. And then want to get back to Lestat. Then there are all kinds of other books I want to do. Also, I still don’t believe I’ve really done a great haunting novel. That was my goal with The Witching Hour, but it became a witchcraft novel. I’d like to do one really about just pure haunting, like The Turn of the Screw. Just have ghosts. I’d love to do that, and I’d love to go back to Egypt. So I have all these stories in my head. I just have to find enough time to spend at the keyboard to write them.

Source: Playboy USA, March 1993

No comments:

Post a Comment