Top 10 books of autofiction

From Karl Ove Knausgård to Marguerite Duras, the French author Nina Bouraoui celebrates the writers whose stories are told without invention

Nina BouraouiWed 16 September 2020

A

She delivers the truth, without altering or falsifying the facts, as if putting together a police report. The power of autofiction comes from its universality. When she tells her own story, the writer describes an expanded world, one that unites us all.

The writer’s own story is the human story, with the same structure and complexity. Autofiction doesn’t arise from the urge to invent, to create a fictional other and tell a tale according to the rules of a particular form. It’s more a way of experiencing the Other as a being similar to oneself: “when I speak of myself, I’m speaking of you.” It may not be the absolute truth the author is telling, but it is her truth as she lived and experienced it.

Towards the end of the 1990s I was asked by the French writer Christine Angot to write an autobiographical novel for her series of autofictions with the general title of Sujet (Subject). I had just started therapy and the analysis spilled over quite naturally into my writing.

I was driven by a genuine craving to write about my origins, my identity, my dual nationality, my sexuality. I felt that in getting to the heart of my own truth, I was also touching on what seemed to be a universal truth. After that I wrote three auto-fictional novels, bringing together my childhood, adolescence and young adulthood.

In 2008, I came back to the more traditional novel, inventing characters and stories that weren’t part of my own experience. I wrote All Men Want to Know 10 years later, perhaps as a response to the times. On the one hand gay rights had become more widely recognised and defended, at least here in the west, but at the same time, we were witnessing a rise in verbal aggressions towards minorities in France, as well as a surge in violent homophobic assaults.

I can lay claim to having a triple status: I’m a woman, I’m of mixed race and I’m gay. With the rise of the extreme right, I felt it was important to tell my parents’ story: a French woman marrying an Algerian man, my mother’s arrival in Algiers after 1962, a time when the French were all leaving Algeria; our life there, full of beauty, poetry and sometimes, danger; the discovery of my sexuality. It takes courage to step outside of the norm and become the person you are. I wanted to affirm once and for all that one’s sexuality, one’s identity has a story of its own, that it doesn’t arise from nowhere, that it is not something one chooses.

I feel affection and admiration for all writers of autofiction and for the books they write. It takes a certain kind of courage to deliver up the truth about oneself. I see it as a kind of political act, too: in declaring who you are, you’re also saying something about other people and about the world we inhabit.

|

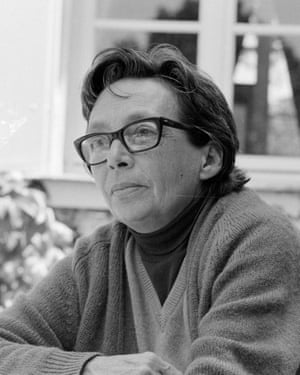

| Annie Ernaux |

5. Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux, translated by Tanya Leslie

This short work tells the story of a woman’s great love. Ernaux’s unadorned prose lays bare the madness of love and the workings of the flesh: expectation, physical tension, surrender – written, as always, with consummate skill. Ernaux never tired of writing of passion and lost love, of the female body and its vertiginous relationship to the male.

6. Incest by Christine Angot, translated by Tess Lewis

With great courage, Angot writes of how an incestuous father ruptured a soul’s equilibrium to the core, fracturing its relationship to love, to the world (in this instance, a conflicted relationship with a woman) and to other people. A work unequalled in its power to give strength and comfort to all abused children.

A love story about a young reader (Yann Andréa Steiner) and his passionate admiration for a woman who writes: Marguerite Duras. This is their story, set in Paris and Trouville, told in words and silence. A window on the world of Duras: a world of books, films, plays – and alcohol. Yann Andréa was Duras’s young gay companion, her first reader and her great love.

10. Consent by Vanessa Springora translated by Natasha Lehrer The autobiographical account of a woman, who at the age of 14 was allegedly groomed by a man in his 50s, the writer Gabriel Matzneff. It tells the story of an adult’s hold over a young girl barely out of childhood. This extraordinary book could not have appeared without the #MeToo movement and the power it gave to women to speak out.

No comments:

Post a Comment