Cartoon marvel

Posy Simmonds

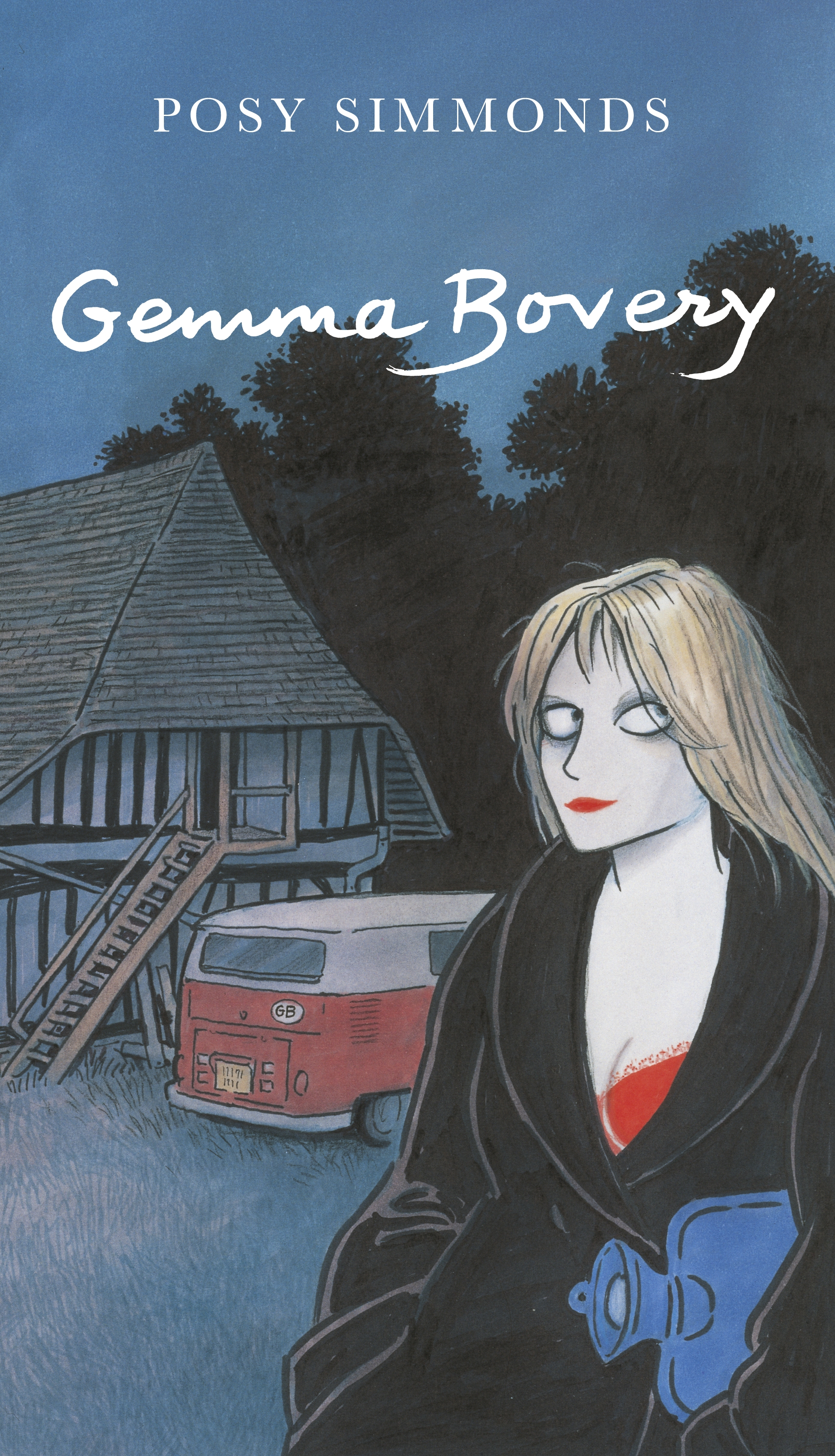

Gemma Bovery

Jonathan Cape

Jonathan Cape

Saturday 7 October 2000

This work needs no explanation or apology to readers of this paper, who felt inconsolably bereft when the strip reached an end over a year ago. (For those of you who have been in prison, or joined us recently from another paper or planet, this was about a couple who move to Normandy to escape the rat-race; the woman has an affair and dies. Buy the book and read it. Let's get on.) In its very early days Gemma Bovery had failed to attract me: thin social comment with literary aspirations, I thought, neither a fully fledged cartoon nor a prose work. Too text-heavy for one, too text-light for the other. And what was all that "Bovery" stuff? Can we try not to rely on the classics?

This attitude lasted for about four days. Not only is a cartoon a cartoon - and therefore, apart from the book reviews, the most enjoyable part of any newspaper - but Posy Simmonds is Posy Simmonds. Like everyone else, I began to marvel at ... well, there is rather a lot to marvel at. Like every single drawing, for a start. From the simplest of lines Simmonds can conjure up a world of nuance and even novelistic insight. I do not exaggerate. Gemma's thought-bubble at the bottom of page 65 told me more than I had ever known about the working of a woman's mind in love. But any drawing of Gemma's face tells its own story with clarity and force. The same applies to her husband, Charlie, whose shifts between dreaminess and irritation are equally well captured. Even the minor characters are treated with equal care; Mme Sannier, for instance, with her pop-eyed, provincial, soigné niceness and cretinous conversation ("la reine Mère - elle a quelle ge maintenant?") - Simmonds gets everyone bang to rights. Her characters have expressions you could write monographs on even when their eyes are represented by nothing more than dots.

But what makes GB so much more than a work of social satire is the way that her graphic line gives everyone, even the most potentially irredeemable, a chance. At the end of page 71, Delphine, Hervé's girlfriend, moves from being a shallowly drawn little BCBG nonentity and, at the moment she discovers Hervé's infidelity, is allowed to become a true portrait. It shows how Simmonds has the ambiguous tenderness of a true creator: almost taken aback by her own skill, one imagines. There is a definite if restrained relish in the way she moves her characters into situations where they can be drawn so well.

There is more than just drawing going on here, of course. There is pacing - GB moves from illustrated text to straight comic strip and back again - and there is the prose, from the narrative frame of Joubert, the nosy, creepy baker (for whom we feel a strange kind of pity), to Gemma's diaries, and down to the speech-bubbles of all the characters. Simmonds has, in this sense, two kinds of blank paper staring at her every morning, and she should be honoured for filling them so perfectly, with such a combination of daring and what looks like effortlessness. That she has to do two nationalities as well - would she perhaps care to make things more difficult for herself next time? And, please, can there be a next time very, very soon? She is the greatest.

DE OTROS MUNDOS

Posy Simmonds / El último crimen de la gran dama del cómic

Tres protagonistas femeninas en tres novelas gráficas hechas por mujeres

Posy Simmonds / Cassandra Darke / Sinopsis

Posy Simmonds / Cassandra Darke, tercera de una ilustre galería

DRAGON

Posy Simmonds / Gemma Bovary / Cartoon marvel

A peek inside the sketchbooks of Posy Simmonds

Posy Simmonds in Conversation with William Feaver

Posy Simmonds / El último crimen de la gran dama del cómic

Tres protagonistas femeninas en tres novelas gráficas hechas por mujeres

Posy Simmonds / Cassandra Darke / Sinopsis

Posy Simmonds / Cassandra Darke, tercera de una ilustre galería

DRAGON

Posy Simmonds / Gemma Bovary / Cartoon marvel

A peek inside the sketchbooks of Posy Simmonds

Posy Simmonds in Conversation with William Feaver

Graphic Novelist Posy Simmonds Retropective Exhibition Opens at House of Illustration

Posy Simmonds / Cassandra Darke / A No-Deal Christmas

Posy Simmonds / Cassandra Darke / A No-Deal Christmas

RIMBAUD

DANTE

No comments:

Post a Comment