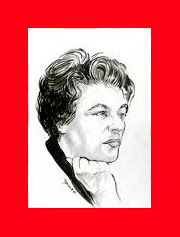

An Interview with Mavis Gallant

Excerpts

BIOGRAPHY

STÉPHAN BUREAU

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY WYLEY POWELL

I must confess at the outset that I was rather terrified of interviewing Mavis Gallant.

I had been a long-time admirer, knew the extreme rigour with which she undertook her work, and, most of all, from my research, sensed that she did not suffer fools gladly. In fact, I knew that she preferred to have her work speak for itself, and that she did not view literary criticism as an art form. Her choice has always been to concentrate uncompromisingly on her craft, to search for that perfect architectural form that lies in a great story. You have to come prepared: a great challenge . . . and a minor source of stress.

We agreed to meet at the apartment of one of Gallant’s Parisian friends, for the author’s apartment was her inner sanctum. A choice I of course respected, although I admit I wish we could have shown Contact’s viewers a glimpse of Gallant’s private world.

Very elegant in a green dress, Mavis Gallant was punctual as a Swiss clock and ready to start the minute she walked in. I was first struck by her smile—a radiant smile that I soon realized was also a way to punctuate what she was saying; a delicate but firm way to mark that we had reached the end of a topic. Her life, the fabric of which I believe is still at the core of her work, was often off limits. That material is hers and not to be shared before it takes its full and complete form in her work. She was generous and forthcoming, but she firmly protects, and for good reasons, a certain core. For that truth, no interview can reveal what can only be found (if it can be found) by reading between her lines.

Our conversations took place in French over a period of two days in mid-December 2005. They were broadcast in April 2006 as part of the television documentary series Contact: The Encyclopaedia of Creation. This interview was edited for Brick with the participation of Mavis Gallant.

SB: Your destiny as a storyteller became apparent very early.

MG: Yes.

SB: Because, in the first place, you were very young when you started learning the alphabet and reading.

MG: Yes. It’s very important for a child to read. I don’t think there’s ever been a writer who was not also an avid reader.

SB: Yes. Moreover, you’ve written: “Writing grows out of reading.”

MG: Yes.

SB: Sometimes you were overheard reading or talking out loud,which was when you realized that the stories you liked to tell yourself were also being heard by the adults around you.

MG: No, I wasn’t telling myself stories. I had an entire colony of characters. I was a little older—six or seven, or even eight years old. They were paper dolls, and I made their clothes, which I put on top of the dolls because they were lying on the floor. I had a little suitcase full of these dolls—of these characters. I would cut them out of newspapers and magazines.

SB: There was also a bit of the director in you?

MG: Well, I’d move the dolls with two fingers. I don’t think you can move the people you’re interviewing with a couple of fingers. [laughs]

SB: That would be too easy?

MG: This took place on the floor and I’d create their voices for the dialogue. Someone who was visiting my mother said, “Does she always talk to herself?” No, it was my mother who said that. The visitor said, “But, what’s she doing? Is she talking?” And my mother said, “Oh, she talks to herself all the time.” You know—all the time. And I didn’t know that people could hear me. It came as a surprise. That’s all.

SB: What fascinates me in what you’re saying is how sharp the details are and how exact your recollections are. I imagine it’s important for an author to be able to call up—

MG: Certain things.

SB: Yes.

MG: Certain things and with an abundance of details. I remember what people were wearing. I remember my mother’s clothes, for example. Not all of them, but there were certain things that struck me. I liked the way my parents looked, how they dressed. They were quite young, in their twenties. I thought they were better looking than other parents. I was proud of them. [laughs]

SB: You notice things, write them down, remain constantly vigilant. Are you aware of this?

MG: I think that’s the way I am. There’s nothing more to it than that. There are lots of things that I forget. If I didn’t keep a diary, there are things I’d forget completely.

SB: I was reading a piece of yours in which you said, “In my early teenage years—when I was fourteen or fifteen, my mother would find my journal and read it. If there was anything I didn’t want read I’d tear it up—I didn’t really want people to read what I was writing.”

MG: Yes.

SB: You also said: “from the time I was young I was haunted by the fear that I had inherited a vocation from my father but not the means to fulfill this vocation.”

MG: Yes, yes. My father would have liked to be a painter, an artist. He was a talented amateur. My great fear, for many years, was that I had inherited something of that from him.

SB: A vocation without talent?

MG: It’s strange because I had every reason to feel reassured. I had sent a short story to The New Yorker. They didn’t know who I was. I simply wrote my name and the address of my newspaper in the corner of a page. And they promptly replied that they couldn’t use that particular story but asked whether I had anything else to show them. Their exact words were: “Have you anything else to show us?” So I quickly sent them something else, which they accepted.

SB: But didn’t you have every reason to think that your talent was up to the mark?

MG: Maybe the editor couldn’t see how worthless it was! [laughs] No, it wasn’t all that bad. But all the writers I’ve known who have to talk about this have had the same doubts. They constantly need “reassurance.”

SB: You had seen your father’s vocation for painting, but you weren’t convinced that he had the talent?

MG: Well, that’s not what I thought when I was a child. As a child, I marvelled at everything my father did. But later I did come to see things in a more rational light.

SB: Speaking of your father, he died at a very young age.

MG: He died young.

SB: You were ten years old?

MG: It was on my tenth birthday that I saw him for the last time. I wasn’t told a thing; everything was kept hidden from me. Since I’ve written on this subject, I can talk to you about it. I was told that he was in England—I wasn’t told that he had died—and that he was going to come back for me. I waited for him from the time I was ten until I was thirteen. Then, when I was thirteen, somebody said, “You mean you still don’t know that your father’s dead?” It was brutal, you know. But that’s how it was.

SB: Having to wait must have been a horrible thing.

MG: Well, children don’t think about such things every day because they’re busy growing up. Children aren’t obsessed. Obsessions come at a later age.

SB: Later?

MG: How could people have been so stupid? But we have to remember how things were back then. Children weren’t told very much.

SB: And later, did you feel you’d been deceived because no one had given you—

MG: Yes, in a crazy kind of way, I think. If people lie to you about such essential matters as life and death, especially when your close relations are involved, a trace of that shock stays with you.

SB: I would suggest to you that there’s more than just a trace.

MG: Do I strike you as abnormal?

SB: Oh, I didn’t say you were abnormal.

MG: No? Good! [laughs]

SB: I said that there’s a trace that remains and that it can be seen in your writing.

MG: I don’t want to give you the impression that I was a poor little orphan, et cetera, because my life wasn’t like that.

SB: That’s not the impression you give.

MG: Good.

SB: After the death of your father, it was just your mother and you.

MG: My mother remarried almost immediately. There were predictable consequences.

SB: In what way predictable?

MG:I didn’t like the man who had taken the place of my father. No daughter likes the person who takes her father’s place.

SB: As a girl and soon-to-be young woman, did you feel somewhat rejected by your mother?

MG: I was the one who left home. I wasn’t rejected.

SB: Was this a case of self-expulsion?

MG: Why are you using such words?

SB: Well, I don’t know, I’m asking you.

MG: I lived in New York from the age of thirteen to eighteen, and when I was eighteen, still legally a minor, I left New York and went back to Montreal.

SB: Yes, and there’s a Linnet Muir story that tells something about this episode.

MG: Yes. My arrival in Montreal was the way it’s described in the story. I arrived after spending the whole day on the train because, in those days, it was a very long journey. No one knew I was coming and there was no one waiting for me. I’d told just a few friends that I was leaving New York. I said, “If you want to tell my mother, give me twenty-four hours,” because I was underage.

SB: At the time, you needed to be twenty-one.

MG: Yes. And I did something worse than that. I got married at twenty, with still a year to go. I could have been stopped because in Quebec at that time rules for minors were very strict.

SB: There’s nothing like that nowadays.

MG: My husband knew nothing about any of this at the time. He wasn’t from Quebec. He’d been born and brought up in Winnipeg. At this time, he was in the RCAF, training in Ontario. I wrote to an American friend, a woman who was older than I. She and her husband had been marvellous to me in my somewhat difficult teens. In fact, at one point I had moved in with them, with my mother’s consent. The husband had known my grandmother, so there was a link.

At any rate, I wrote a letter, saying I needed consent to get married and could she give it to me. Well, she wrote a perfect answer, “To Whom It May Concern . . .” just saying that, as far as she was concerned, I could marry John Dominique Gallant. She didn’t claim any relationship or legal authority. She said just that. And so I was married. I told him later about the letters. He said if he had known, he would have asked his favourite aunt to write it. But it wouldn’t have worked. She might have written something like, “. . . permission to marry my beloved nephew, John et cetera . . .”

SB: Today when you look back at the period that followed your father’s death, does all that moving around now strike you as having been a difficult time?

MG: Between the ages of ten and eighteen, let’s just say that it wasn’t much fun. But, as soon as I had found my freedom and was in Montreal and had hopes of staying there for a while, I was quite happy.

SB: You’re going to be quite annoyed with me, but, a little while ago, you took me to task for the words I chose—I believe I used the word self-expulsion.

MG: Yes.

SB: And just now you said, “When I found my freedom.”

MG: Yes.

SB: I find that expression rather strong. Freedom from what? From that life? From your mother?

MG: From my youth. I was eighteen and I found youth difficult because I had to depend on someone else; and I didn’t like that. You know, there were all those constraints: “Do this, do that.” I decided—and I remember this well—that never again would anyone tell me what to do. And that was in the taxi; I still remember it, when I arrived in Montreal.

SB: In the taxi that was taking you to . . . ?

MG: That’s about all I remember. I recall that extraordinary feeling of freedom.

SB: You were eighteen and you were taking control of your life?

MG: Yes. Yes. And I did it. I didn’t have a penny.

SB: You were leaving New York to return to Montreal.

MG: Yes.

SB: Where people thought you were dead?

MG: Yes, but I didn’t know that.

SB: That was extreme freedom indeed—returning to a city where people thought you were dead.

MG: Oh, I wasn’t shocked. Later I looked up people who had known my parents because I wanted to find out what had really happened. And they thought I was dead.

SB: When thinking about your life, isn’t freedom the keyword?

MG: Autonomy. I was aware that we live in a society; and it’s possible to be autonomous within a society. I had my autonomy and was determined to keep it.

SB: And you still are?

MG: Freedom would be the appropriate term if I had been in a fascist country where people were oppressed and I was part of a freedom movement. That’s something else. But, as for personal autonomy, I was enormously set on that. And I have kept it.

SB: Proudly?

MG: Essentially.

SB: In the next few hours, semantics will be playing a big role. Essentially . . .

MG: No, because we need to be specific.

SB: Absolutely.

MG: And don’t forget that I don’t speak French as I do English. That’s why it’s essential to have the right word.

SB: Always.

MG: Yes.

SB: So, autonomous is the word.

MG: If we were speaking English, I’d say, “You know what I mean.” That would be it.

SB: But we have a very good idea of what you mean. For a young woman who was still underage, such autonomy—

MG: I wasn’t yet of age. I’d never done anything. And suddenly, here I was barely out of high school—

SB: So, autonomy has to be earned?

MG: Well, it’s something you have to achieve. You mustn’t let yourself be influenced. If you want your autonomy, you have to be really set on it. This can also be very irritating for other people. At the newspaper where I worked, there was one editor—the one who told us what to do—you know, the one who assigns you a story about four dogs that got run over, et cetera.

SB: The one who gives the assignments.

MG: Take a picture of this or don’t take a picture of that. It was obvious that I didn’t get along with him. I tried not to show it. One day, quite a bit later, I was visiting Montreal—that was about fifteen years ago—and I ran into him on the street. Back then, he’d had red hair, but now he was grey. We talked. He said, there in the street, “I know you never liked me, but you’ve forgotten what you were like. You never accepted an assignment without more or less saying, ‘Why do I have to do that when I want to do this, or why do I have to do it that way when I want to do it this way?’ And it would be better if I went to see such-and-such a person before going to see that other person.” And he said, “It was like that all the time—all the time.”

SB: Strong-minded, weren’t you?

MG: Well, I didn’t realize just how much I got on his nerves, but he was the one . . . I’ve written about this. I’d once gone up to the poor man and said, “Listen, this week Jean-Paul Sartre and Paul Hindemith, the composer, will be in Montreal. I’d like to cover them both. Each of them will be holding a press conference and I want to cover them and I want a photographer and I want . . .”

SB: I want . . . I want . . .

MG: “I’d like to have.” Yes. [laughs]

SB: “I’d like to have.”

MG: He was sitting down and I was standing up. Then he said, “Who?” I said, “Jean-Paul Sartre and Paul Hindemith.” He said, “Listen, Mavis, I’m sick to death of these French-Canadian geniuses that you’re always trying to cram down my throat.”

SB: Jean-Paul Sartre—now that’s a good one!

MG: Yes, and it was also appalling as far as Hindemith was concerned. And guess what I did. I did something one should never do at a newspaper: I went over his head to a much more senior editor.

SB: Another authority?

MG: That’s something you should never do unless you want to make enemies. I’m warning young people not to do it. But that’s just what I did. He was more reasonable and said, “Well, there’s a press conference for Sartre. Yes, okay. But you’ll have to cover Hindemith on your own time.” I replied, “That’s fine. He’s going to give a lecture I’ll be going to anyway.

SB: You don’t seem to have many regrets concerning the person you were at that time or for—

MG: No, but I’ve always been amused by that “Who?” of his. Don’t forget, however, that Sartre, as far as I know, had not been widely translated at that time. It was 1945. The war was over. A group of French reporters came to North America from France. The Americans brought them over. Jean Paul Sartre was among them. You must know the story: they were shabbily dressed after four years of war and occupation. So, the first thing the American authorities did was to provide them with clothes. They took them shopping and bought them something to wear. But that’s another story.

SB: When you arrived in Paris, did you have any idea that you’d spend your life here?

MG: No, I had no idea what was in store for me. None whatsoever. But I had a typewriter, so I started writing.

SB: In a rigorous and disciplined manner?

MG: Well, I made the time to write. I’d have been stupid not to. But after a month at the hotel, I was seeing too many Canadians because everybody wanted to come to Paris. There was Mordecai Richler, who was nineteen. I had met him in Montreal—John Sutherland introduced us. I met more Canadians in Paris, in 1950, than I’ve ever known since.

SB: It seems to me that throughout your career as a short-story writer, you’ve drawn on your experience as a reporter. That’s rather curious. Because, to say the least, the use of words could be seen as a link between your earlier experience as a reporter and your literary career. But bringing a reporter’s eye to your way of writing strikes me as quite innovative.

MG: I’ve often been criticized—but nicely—for questioning people in the way a reporter does. For instance: “Do you have any brothers or sisters?” I’m not even aware of doing this.

SB: Does the writer, the author, sometimes work as a reporter?

MG: Oh yes! But unconsciously so. As a reporter you quickly feel the atmosphere of a house or of a place you’ve never been in before. It speaks as much as the person you’re there to interview.

SB: And with a minimum of words?

MG: Oh, that’s essential!

SB: It seems to me that this would also be true for the writer.

MG: Yes. I take a knife to what I write. I cut a lot, really a lot. And I’ve written only two novels. Some time ago, I started another novel; I then reread what I’d written and it struck me that this book had only three important things in it. So, what about all the rest? Why was it there? I removed those three things and they became three long short stories—which you’ve read. Unfortunately, in the French translation, they were arranged in the wrong order, which must have made for difficult reading.

SB: But, in your view, does the short story go right to the heart of things? Does it immediately go to the most urgent aspect?

MG: It shows people in a given situation. And the tension either eases or it doesn’t.

SB: Is tension important?

MG: Well, if you take a look at life or remember your own life, it’s . . . it’s . . . tension. I’m sorry, but I can’t really explain.

SB: No need to apologize. We understand by reading your works. You don’t need to talk about them.

MG: Good, because I’m not a teacher and I can’t analyze what I do. I can be a critic. I’ve been asked to review books, but I can’t analyze my own work. Other people tell me things that amount to clichés. For example: “All of your subjects are about exile.” That’s not true.

SB: People talk to you about exile?

MG: Constantly. And it’s not true. I’m not in exile. You’re in exile when there’s a party in power in your country that you oppose; you then go off to live in Patagonia because you think you’d rather be in the company of horses than with your countrymen. That’s what exile is. But when you leave on your own accord, with no bitterness . . . Absolutely no one was malicious toward me in Canada. Back then, people did talk about men’s attitudes to women, but, I repeat, that was a sign of the times. It was the same elsewhere.

SB: It’s my impression that your short stories deal more with fragility, with the loss of a beloved person, a lack. Often your characters seem to me to be in situations of this type.

MG: I don’t know.

SB: You don’t know?

MG: No. If I analyzed what I’ve written, I wouldn’t amount to much. I’d have nothing left. I read what other people write.

SB: Is what they write sometimes accurate?

MG: Sometimes—namely, when it coincides with my own thoughts—but sometimes it’s off target. Even when it’s kind, it’s still off target. It couldn’t be otherwise. I keep very few reviews, very few. One that I liked and did keep appeared in El Pais. I’d just published a translation in Spanish and the reviewer said, She came to Western Europe after the war; no one knew who she was and she didn’t know anyone. She lived as anonymously as possible with an exercise book, a notebook and a pencil. She was like Kafka’s invisible woman and the invisible woman took note of everything that Europeans thought was of no importance. And now people see that it was indeed important. I really liked that.

SB: Does a short story have a gestation period?

MG: The beginning of the story doesn’t. That part comes very quickly and it can come at any time. You may be brushing your teeth when an idea strikes you. You drop whatever you’re doing because if you don’t immediately write down what comes into your head, you’ll lose it. It’s like a dream, you know—you’ll forget it if you don’t write it down at once.

SB: So, it’s an idea that whizzes by at lightning speed?

MG: A flash. I’ve already compared it to a play when the curtain rises and you see the stage. You don’t know what’s going to happen, but you know somebody is going to come on stage. If it’s a light comedy, somebody will walk on and answer a white telephone. But that’s only the beginning, and you know nothing yet about these characters. The difference—when you’re at the theatre, I mean—is that the characters walk on stage; and, if it’s not a play that’s been performed a million times, you don’t know what’s going to happen. So you wait to find out; you wait for someone to say something. But with a work of fiction, if nobody makes an appearance . . . I’m speaking from my experience. Other writers may tell you something different. John Updike sees the beginning of a novel—I read this somewhere—as a blob on the horizon. Not so for me. I see faces, the faces of living people, even though I’ve never actually laid eyes on these people. You may wonder where these faces come from. I don’t know.

SB: So, it’s always the characters who—

MG: It all starts with the characters. They are what make literature. That’s how it begins—not with a sunset. You must avoid sunsets. If that’s how a work starts, don’t read it.

SB: If it starts with a sunset, stop reading immediately!

MG: Yes, right away. You can even burn it!

SB: Your dialogues are often extremely complex. There are times when a dialogue is taking place inside the head of a character at the same time he or she is also talking with another character. This use of multiple levels is quite a gymnastic feat. The dialogues are very significant.

MG: What’s said is significant. What’s being thought is also significant.

MG: What’s said is significant. What’s being thought is also significant.

SB: When you make corrections—or, I should say, when you reread what you’ve written—you strike me as a very demanding reader as far as your own work is concerned.

MG: Yes. I have to be. I can’t write just anything, especially in a brief piece like a story.

SB: Indeed, you don’t seem very lenient on yourself.

MG: No. I don’t know whether you’ve read a story called “La femme soumise” (“The Moslem Wife”). . . . Well, I saw a lot of myself in that woman but not until quite a bit later.

SB: She’s a very modern and very autonomous woman. She may be like you.

MG: But that wasn’t the issue. When the doctor asks Netta, after the war, to marry him, or to live with him—just as she chooses—she refuses. She’s waiting for her husband to return. And he, the doctor, says, “Don’t be too hard on Jack.” Her answer is, “I’m hard on myself.” When I reread that passage I thought, I could easily be the woman saying that.

SB: Were you merciless with yourself?

MG: No. Please don’t say that. On the contrary, my life has been very pleasant compared to—

SB: I’m talking about when you’re rereading what you’ve written, when you’re working.

MG: In that case, yes. But it wasn’t a case of forced labour for me—not at all. If that had been the case, I’d have made a mess of my life. I think you understand that. The American writer Elizabeth Spencer wrote in her memoir, “Get up in the morning, write and you’ll see that you’re happy.” I agree with that.

SB: You got up, you wrote, and you were happy?

MG: Yes. One is not unhappy at such times. Sometimes things go badly and you tell yourself it’s worthless and that you’re making a mess of your life writing about people who don’t exist. Because it’s strange spending your life writing about people who’ve never existed. In a way, it makes no sense.

SB: Have you ever been afraid that the characters will no longer appear in a flash, that there’ll be no more characters who compel you to tell their stories?

MG: No. But it’s different as I grow older. You reject more than you accept because you can already see where you’re headed. But I do prefer a little mystery all the same.

SB: Because you know all the strings?

MG: Well, I can see that either I myself have already written about such-and-such or that various other people have done so. I stop there. But at an earlier time, it didn’t interest me whether someone else had already done it.

SB: Are you now more critical about your work, about those flashes, at an earlier stage in the writing process?

MG: Perhaps. I don’t know.

SB: When you decided to write fiction full-time and to come to Paris, you gave yourself two years.

MG: Yes.

SB: For you, what was the stage when you could say to yourself, I have what it takes to be a writer?

MG: The desire. The desire to do it. That’s all. The desire to live in a certain way . . . and I made the effort. You know, there’s no point in wishing to live in such-and-such a way. You’ve got to try. And if it works, so much the better.

SB: Have you ever had any regrets?

MG: No, sincerely, no. You may look me in the eye and I will tell you that I have no regrets.

SB: In those early days, did The New Yorker play a significant role?

MG: A huge role! Huge! If it hadn’t been for The New Yorker, I don’t know what I would have done. My situation would have been difficult, even impossible . . .

SB: . . . without this magazine. You also worked with an editor.

MG: Yes, William Maxwell. He was a great writer whom I very much admired, but I didn’t realize that the editor was the same William Maxwell. Though I finally did realize he was the same man.

SB: So, if it hadn’t been for The New Yorker, the path would have been very different?

MG: It would have been very different.

SB: Since you were probably well paid, did you find it hard to accept—if accept is the right word—the fact that it was the Americans, and not your fellow Canadians, who first opened their pages to you?

MG: Oh, I was unknown in Canada. I was unknown or rejected for a long time. There was a time—especially in the 1970s, in the period 1960 to 1970—when Canadian nationalism became very intense. This was a stage that the country probably needed to go through at that time.

SB: So much the better if you were fairly well paid. But were you affected by the fact that your initial good fortune led to publication in The New Yorker rather than at home?

MG: You know, I slid into another life. There were no great revelations or extraordinary moments in which I said to myself, That’s it! No, not at all; I was going in a certain direction, like a river. That’s all.

SB: But what about the fact that you found no immediate resonance at home?

MG: Well, the immediate resonance was that I had very little money. Do you know who else was in the same situation? Anne Hébert. We were close friends. I had met her in France in 1955 and neither of us had a thing. Then we learned what it meant to be broke in post-war Europe. But one can’t write on command. For the most part, I was writing short stories and usually had a novel in the works on the side—but I was never satisfied with it. The New Yorker was very generous toward its writers. It was a unique situation. I don’t think there was anything really like it anywhere else in the world. So, I had money and spent it. And I had to pay for all the things I’d not paid for in the meantime, you know. It was harder for Anne, until she had an international reputation.

SB: Does it bother you that you weren’t published first in Canada?

MG: No.

SB: Are you completely indifferent to that?

MG: Well, you know, there were very few publishers. It affected me later when that wave of nationalism was still going on. The same thing happened to Mordecai Richler because he was living in England with his family.

SB: To some degree, you idealized life in Europe because of certain great English-speaking authors, such as Fitzgerald, Miller, and Hemingway, who had made Paris their home during an earlier time in the city’s history.

MG: Fitzgerald was the one I admired—admired a great deal. Not for the way he lived, because he wasted his life. He didn’t waste his life in terms of his work, however, because The Great Gatsby is without peer as a novel. And he was a great, great writer! But people dared to judge him because he was a drunk. That’s how it was. But they had no right to. Only the work matters.

SB: The things that can be found on the other side of the book.

MG: We need to separate the artist from the art. Visitors wouldn’t look at anything in museums if they knew everything about all the painters. We’re now living in an age that is extremely open, but, on the other hand, it is a puritanical age; and people want to know about the individual, his life, what the person does. More and more biographies of writers and artists are being written in an attempt to bring them down a notch. It is reassuring to a certain audience. I don’t mean to every audience but to a certain audience.

SB: That’s not so bad either.

MG: Well, it’s worse if these people take drugs and have five wives at the same time. They’re good-for-nothings. But you, on the other hand, are decent, clean, and noble and you brush your teeth five times a day. So, be happy.

SB: And avoid being a dropout or an eccentric.

MG: More importance is attached now to the biography of an author or painter than to the writer or artist. Just look at the frenzy surrounding Picasso—the women he married, the mothers of his children. What difference does any of that make? It’s irrelevant.

SB: Only the paintings matter?

MG: Only the work life. That’s the life that matters.

SB: What is it that makes us prefer these famous people to what they do? There is more interest in the celebrities themselves than in knowing about their vision.

MG: Well, people can stop doing this. They read or learn this and that and they can talk to you about these things, but they can’t talk about the work itself. They read much less nowadays. But I know I’m not going to change anything by telling you this. That’s my opinion.

SB: In an ideal world, an author or painter would hand over his or her works to the public and say, “Judge me on these.”

MG: Perhaps these works could have numbers on them rather than names. I might be, for example, number 16. People would then try to put a face to number 16 but wouldn’t be able to. That’s how it would be.

SB: Would that be better?

MG: No. I’m joking, of course.

SB: But, at the same time, as soon as you begin to attract media attention by exercising your profession, you become less anonymous.

MG: I lived in virtual anonymity for years. The work was translated late. I was reluctant. I felt that nothing would work in translation, that I wrote in English for English-speaking readers. When it began to happen I was afraid it would change my life in a way I’d regret.

SB: Things are going to change?

MG: Yes. It was in the 1980s. A writer friend in Paris said to me, “You’re being coy about translations. As you get older, it seems absurd.” But it’s ridiculous!

SB: Not to have achieved sufficient success or not to be translated?

MG: Not to be translated is a form of coquettishness. But I wasn’t . . . . We’re going to avoid that.

SB: Why?

MG: Because! But here’s what happened in Canada: a Scottish editor and publisher working in Canada wrote to me about a book, From the Fifteenth District, that had just been published in the United States, wanting to know if the Canadian firm could publish it under their own imprint. By this time, I had been published in New York and in London for some thirty years. It was the first offer or suggestion of its kind in Canada. After that, the same Scot wrote to ask about an idea of his he thought I’d refuse: a collection of stories set in Canada or with Canadian characters living abroad. I remember telling him that I hoped his shirt was painted on his skin, because otherwise he was bound to lose it. He didn’t lose it, and the book, Home Truths, received a Governor General’s Award for fiction. Since then—the early 1980s—everything has been smooth sailing in Canada.

SB: I’m wondering just how well it serves you, as an author, not to be too much in the limelight, to keep your distance?

MG: I’m fairly anonymous.

SB: It’s more—

MG: It’s more comfortable. Yes.

SB: And the author has more freedom of action as well?

MG: Yes. As for the journalist still living inside me, you know, it’s a curious . . . a good thing, because I still observe things.

SB: And I imagine that you don’t want to spoil your material by talking too much about it?

MG: Oh, as soon as you begin writing something, you mustn’t talk about it when it’s only half done, because your own interest will fade. It’s like something that’s worn out, a half-smoked cigarette, you know, something like that.

SB: We were talking about Home Truths: Selected Canadian Stories a little while ago and I recall an anecdote I read about Linnet Muir. What kind of name is Linnet?

MG: A linnet is a bird. Just as Mavis is a bird—a thrush. I was looking for a name. There were two possibilities: Merle, which is a girl’s name in English, or Linnet, which is a small bird no bigger than that. So I used Linnet, which I thought was a prettier name.

SB: This cycle is very much about Montreal and is also fairly autobiographical.

MG: Not the whole book.

SB: Of course not, but some episodes are.

MG: It’s a cycle of about five short stories, I think. Four or five.

SB: I recall an anecdote in which your editor once implied that these Montreal stories were perhaps less inspired than some of your other works.

MG: Oh! That was an editor at The New Yorker. Shall I tell you about that? I was stopped in my tracks. I had written four or maybe five Linnet Muir stories. William Maxwell had retired. He was forced to retire because of his age and really didn’t want to. But he did. And then, a young editor—much younger—took over from him. I was completely absorbed in what I was doing, writing one story after the other. This young editor wrote to me, saying, “Some people around here have been saying they wish you would go back to writing real stories.”

SB: As opposed to false ones, no doubt?

MG: That stopped me dead in my tracks. Dead in my tracks. I thought, But who are these people? No one had ever mentioned them to me. When William Maxwell was the editor, I didn’t know that what I sent him was being read by other people. I thought it was only Maxwell and the magazine’s legendary editor, William Shawn. I didn’t know that just anybody could have a say.

SB: Especially if they didn’t like it.

MG: No, it was perhaps the feeling of having been read by people I knew nothing about. But I was certainly stopped in my tracks.

SB: Was that hard on you?

MG: The whole Linnet sequence went dead in my mind. I tore up the one I was then working on and never wrote another.

SB: To preserve your memory of something, you may need to be at a distance from it and out of sight of the changes. Don’t you find that an interesting idea?

MG: Yes, you’re absolutely right. When I think of Montreal, when I have some particular reason to think about it, I see it the way it was when I was young. I can see the tall trees in the streets where they were chopped down long ago; when I go back, that’s how it is now. But I quickly forget. By the time I’m on the plane, flying back to Paris, I’ve forgotten the present-day city.

SB: It’s the Montreal of your youth that stays with you?

MG: Especially Montreal as it was in the 1940s during the war and the post-war, when I was working at the Standard. You always have other, earlier memories of the days when you were very young because the trees looked huge and you were small. Things were different. There are also the well-known true stories about returning to see a house where you lived as a child. In your memory, it’s like the Palace of Versailles. But it’s a more or less ordinary house, like any house, with a door, a staircase, et cetera.

SB: For an author, childhood remains very fertile soil because of those first impressions.

MG: Yes. I even think that’s what counts in terms of nationality—what’s essential to memory. Everyone comes from somewhere. It’s not so much from Daddy, Mummy, Grandmother, that very young schoolchildren learn to be the centre of the universe. This comes from sitting in class with their little ABC books. There are people all around you when you are a baby, when you are young. You’re the centre of the universe—all children are—for better or for worse. It may be an unhappy universe if you’re the child: an orphan in Bangladesh or a baby who will live only three months. In France, I’ve often been asked, “But why have you never taken out French citizenship?” One can’t become something. That’s my opinion. I’m Canadian, I was born Canadian, and I learned to read and write in Canada, in English and in French.

SB: I would put to you, moreover, that one’s identity resides at a level even lower than the national level. Identity is linked to the neighbourhood where a person is brought up. It’s the culture that has had a direct impact on us.

MG: It’s culture in its very smallest incarnation. But I do think that where you learned to read and write and count, et cetera, is, in a certain way, very much related to a particular country.

SB: So, fifty-five years after you chose Europe and Paris, you’re still, in a certain way, that young person who left New York at eighteen.

MG: Well, I’m going to tell you something: when I’m here in Europe, I’m Canadian. I’m asked what I am. I’m Canadian—that’s all I say. I don’t want a second passport or an American passport, which I could have had because I spent five of my teenaged years in America—and that’s how many years you needed in those days. I could hold a British passport because I had the right grandparents. I could probably apply for a French passport considering the number of years I’ve been here, but I’d not be a real French person, nor a real American, and especially not a real British person. And I’d not want to show a passport and say, “That’s not me.” I don’t know whether I’m making myself clear.

SB: Indeed you are. So, it means something.

MG: It has nothing to do with patriotism and nationalism, which I detest. I loathe that. I don’t want to hear anything from anyone about any country. I can listen for five minutes, maybe six.

SB: I’m not even sure! I have the impression that you have a very visceral reaction when people talk about nationalism.

MG: Because, in my view, it leads directly to some very nasty consequences.

SB: The experience of the Second World War.

MG: Oh, the experience of the twentieth century. And this one isn’t so pretty either.

SB: So, being Canadian does mean something?

MG: It’s who I am.

Stéphan Bureau is the host and producer of Contact, a series of in-depth interviews with prominent figures from the artistic, literary and intellectual world. Mr. Bureau was the New York and Washington correspondent for tva and anchorman for Télévision de Radio-Canada’s national newscast.

No comments:

Post a Comment