Hong Kong in Revolt: A Conversation with Au Loong-Yu

Written On 10 September 2020

Author: Ivan Franceschini And Au Loong-Yu

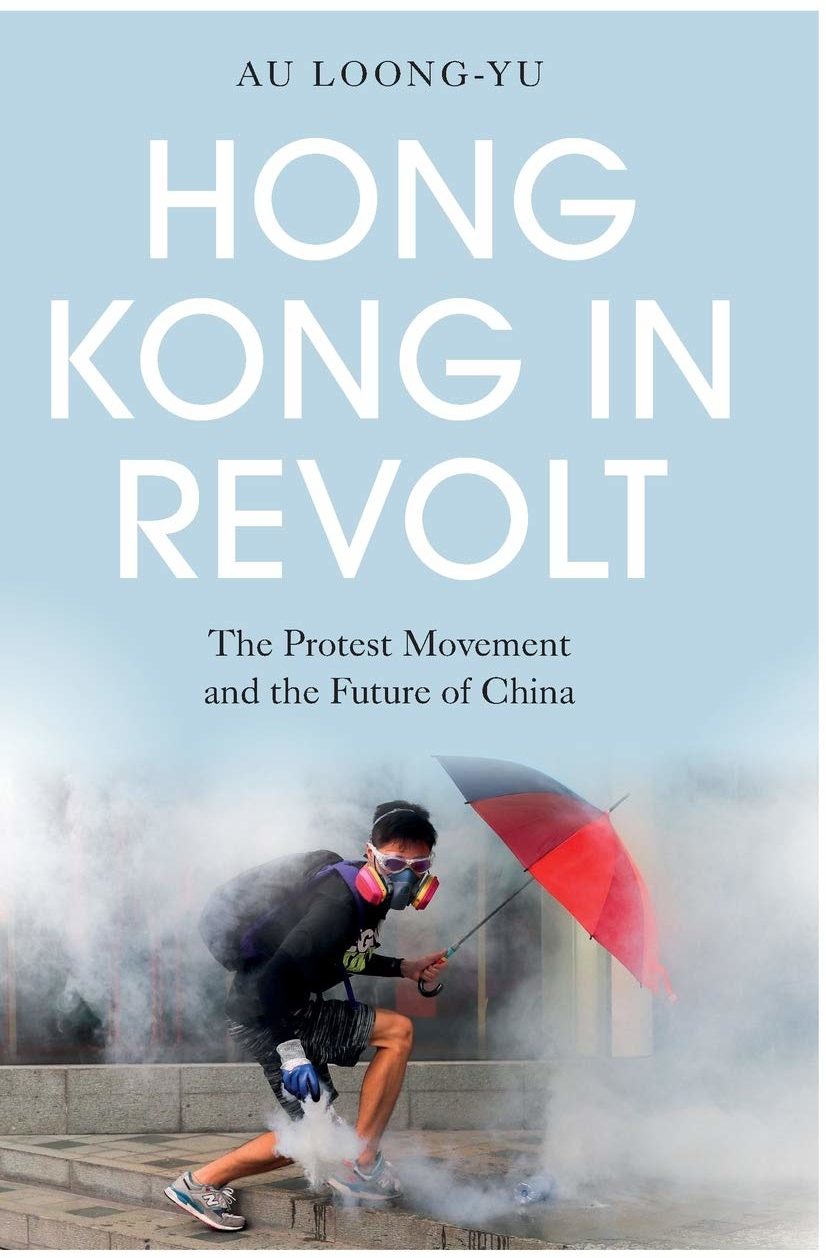

For the past year and a half, Hong Kong has been in turmoil, with a new generation of young and politically active citizens mobilising to protest Beijing’s tightening grip over the city. In Hong Kong in Revolt: The Protest Movement and the Future of China (Pluto Books 2020), prominent Hong Kong leftist intellectual Au Loong-Yu retraces the development of the protest movement in his place of birth over the past two decades, setting it within the context of broader political trends in mainland China and beyond. Published after the Chinese authorities enacted a new draconian National Security Law that effectively signalled a new stage in the crackdown, this book provides a perfect opportunity to reflect on the events of the past months, dispel some myths, and, possibly, draw a few early lessons.

Ivan Franceschini: Looking back at the protests over the past year and a half, and further back to the other mass movements that have taken place in the city over the past decade, is it possible to find a single thread that unified all these instances of civic unrest? In other words, what was it all about?

Au Loong-Yu: One can summarise all the main protests in the past decade in one word, namely ‘disillusion’. Increasingly, Hong Kong people have been disillusioned with Beijing’s empty promises of ‘Hong Kong people running Hong Kong’ and universal suffrage. In 2010, under pressure from the pan-democrats for universal suffrage, Beijing made the concession of granting five more directly elected seats in the Legislature. However, this was rejected by the radical democrats because the increase in directly elected seats was to be balanced by an equal number of indirectly elected seats, which would facilitate Beijing’s manoeuvring. The Basic Law of Hong Kong, unless Beijing revises it, is only valid for 50 years. In 2010 one-fourth of this validity period had passed, but universal suffrage was still nowhere to be seen. Since then, Beijing has begun to roll out a greater offensive against Hong Kong’s autonomy. Firstly, in 2012 they made the Hong Kong government push for compulsory ‘national education’ to promote their version of ‘Chinese identity’. This was followed by the imposition of Mandarin as a teaching medium in Chinese language lessons, which amounted to denying local students the right to use their mother tongue—Cantonese. This was bitterly resented by students, and the most radical of them, led by Joshua Wong, founded Scholarism to oppose the new policy. Even parents organised themselves to support the students. Both campaigns succeeded in stopping the government from implementing its plan. Beijing’s offensive has served to convince the more radical democrats and the young generation that they must act quickly and resolutely to fight for universal suffrage, which eventually led to the 2014 Umbrella Movement. This was the first time in post-war Hong Kong that there was such a massive and peaceful civil disobedience, and it started with the high hope that if it could win the support of local people, then Beijing would have to listen. The movement did indeed get massive support, but Beijing refused to listen, and this broke the hearts of many, who felt deeply that their 79-day occupation had ended with nothing. Behind this lay a deep disillusionment with Beijing as well. A mixture of anger, demoralisation, and despair descended upon the young generation.

The protesters would not have been able to launch a second big wave of protests if in 2019 Beijing had not started another round of offensives, this time with the Extradition Bill. The protests, with millions of participants and the young at the forefront, were larger, sometimes violent, and lasted much longer than the 2014 movement, continuing for eight months until the onset of the pandemic. They knew the bill implied the end of Hong Kong’s autonomy and hence the term ‘end game’ (终局之战) repeatedly appeared among protesters.

But there is another dimension of ‘disillusion’. The last decade saw a growing disillusionment in relation to the pan-democrats, firstly among young people, followed by a significant section of the pan-democrats’ traditional supporters, either middle or lower-class people who once believed in moderate politics—that we should not push Beijing too hard, that civil disobedience was too radical, etc. Most pan-democrat parties had been so pacified by the (partial) electoral politics that they had lost sensitivity to how common people felt about Beijing and also lost the appetite for confrontational actions. Their poor performance in 2014 made the young despise them. The largely spontaneous and leaderless 2019 Revolt was a response to their impotency in initiating a movement from below. It signifies the death of the old politics and the (difficult) birth of a new one.

IF: The new National Security Law is being looked upon as the end of Hong Kong as we used to know it or, in the most optimistic readings, as the dramatic conclusion of this latest, extraordinary season of popular mobilisation. Do you think that such pessimism is warranted? Is there any silver lining?

ALY: I think that if a strong dose of pessimism, at least in the short term, is warranted, it is more because of the reason for the defeat rather than the defeat itself. We were defeated simply because of a severe imbalance of power—in this type of confrontation we would never be able to match the monolithic state. The absolute majority of protesters, although very sympathetic, continued to stand by and watch ‘the braves’ (勇武派) physically confronting the police without ever joining their fight. There is a rationale here. Even common people know by intuition that a successful revolution in a single city was inconceivable. The vanguard of the movement, the ‘1997 generation’, themselves had no answer to this question. Herein lies the greatest weakness of the Revolt—the lack of a strategic outlook. The movement was very good at tactics, but not so much at strategy.

In my view, the Hong Kong movement must seek its allies not only internationally but also, more importantly, in mainland China as well. We also have to admit that Hong Kong’s freedom is a long-term struggle. This implies that the Hong Kong movement has not been able to resolve the tensions in its relationship with mainlanders, and needs to figure out how to avoid alienating mainland Chinese, including those who immigrate here.

My book discusses one big protest on 7 July 2019 that aimed to approach mainland visitors to persuade them about the cause. The activist who called for this march expected only 2,000 protesters, but 230,000 people turned out. They went to the terminal of the high-speed train that runs between Hong Kong and the mainland so as to meet mainland visitors. While the police expected clashes, it was amazing to see protesters approach mainland visitors in a friendly way. Therefore, we can say that seeking allies in the mainland was still in the minds of many. As a whole, however, while it was natural for the movement to seek allies in the West and Japan, this was not the case for finding allies in the mainland, hence the voices advocating for the former were always much stronger than those for the latter. Surely this should not be a choice of either the former or the latter, we could, and should, do both. But as a whole the movement failed to pursue a conscious alliance with mainland Chinese people and groups. If it had done that, whatever the direct result, it would still have been beneficial—less in the sense of any immediate success, more in the sense that we could have avoided making mistakes such as tolerating the right-wing localists’ attack on all Chinese as supporters of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and it would have fostered longer-term potentials for solidarity. Beijing jumped to seize the opportunity to attack the whole movement as anti-Chinese so as to alienate mainlanders from the movement and stop them from sympathising with Hong Kong protesters. To a certain extent it succeeded.

The movement did have a loose strategy, or its ‘vision of Hong Kong’, reflected in the slogan of gong zung keoi gaak ( 港中区隔) or ‘segregation of Hong Kong from China’. Behind the slogan is also a pro–West sentiment. All the evil comes from Beijing and all the sympathy for our struggle against Beijing comes from the West or from Japan—this is what many have felt. The role of mainland Chinese does not appear in this political formula at all. There are rationales to this sentiment, but since it was, and is, not backed by any serious analysis, with no clear boundaries ever laid down, it often plays into the hands of the right wing, who have tried, sometimes successfully, to channel certain protests into potentially Sinophobic attitudes and openly pro-US establishment sentiments. Unless we can come up with a clear strategy to seek an alliance with the mainland Chinese as well, Hong Kong people will remain isolated.

The rationale for optimism in the medium term is that people do learn over the course of struggle. Since 2014 the Hong Kong people, for the first time, have been greatly politicised and have mobilised to take back what has been owed to them. From a historical point of view, this is just the first stage in a new era of popular re-awakening. The movement’s ‘five demands’ speak for this. In terms of party politics, although the right wing has been more vocal, neither they nor other opposition parties are big. This implies that all political tendencies visible in the 2019 Revolt are far from consolidated. The struggle for a progressive course of actions is still in front of us.

IF: With the benefit of hindsight, do you think there was ever any chance that Beijing would ease up and heed the demands coming from the people in Hong Kong? What lessons would you draw from this whole experience?

ALY: I did not subscribe to the idea that Beijing would really accommodate Hong Kong people’s wishes to run their own domestic affairs. What it has done since the handover of Hong Kong in 1997 is a clear indication. Six years after the handover it tried to impose the National Security bill on us. We defeated it. For a while it was a bit quiet but actually its offensive only took a more concealed form. More than a decade ago I noticed two things that symbolised the new offensive. Firstly, Beijing began to organise thugs to confront the Falun Gong people here, whereas previously it just ignored them. Actually, not many people were attracted by their beliefs, but with the rapid increase of mainland visitors to Hong Kong, Beijing now seemed to be concerned that these people might be converted by the Falun Gong, hence a change of tactic. Secondly, Beijing began to coordinate between its Hong Kong Party machinery and mainland local governments to found hundreds if not thousands of ‘Fellow Villagers Associations’ (同乡会) to rope in those who had migrated from the mainland to Hong Kong. These organisations proved to be vital in getting votes for pro-Beijing parties. The pan-democrats hoped to soften up Beijing’s autocracy through closer ties, but what happened is that it is we who were changed.

Similarly, Western countries had pursued ‘engagement’ with Beijing, in the hope that they could give mainland China a push towards political liberalisation through more trade. In general, I have never been optimistic about this. I describe Beijing’s regime as overly rigid in its version of ‘Chinese characteristics’, which is essentially a return to the political culture of imperial China. Xi Jinping’s 2017 speech about power having to be passed down to people with ‘red genes’ (i.e., the second red generation) is a manifestation of that practice. Fei-Ling Wang’s 2017 book The China Order: Centralia, World Empire, and the Nature of Chinese Power well captures the pre-modern aspect of this regime, but he left out the modern aspect of the CCP, namely its ambition to modernise China, or in Mao’s words ‘surpassing first Britain and then the United States’ (超英赶美). Behind its faith in its pre-modern values also lies a very modern, very material thing, namely the fundamental interest of its rule. It combines both the coercive power of the state, armed with the most modern weapons and technologies, and the power of its industrial and financial capitalism. It succeeds by running simultaneously on two sets of rules, the law and the hidden rules of the bureaucracy, with the latter always overriding the former. Its rulers find this regime serves their interests well. From the top to local level, Party officials have enriched themselves tremendously because of this. The more they do this, the dirtier secrets arise that they need to hide. This, in and of itself, is a reason why the Party officials cannot tolerate dissident views. The Party requires the construction of an Orwellian state in the mainland and, imperatively, this must expand to Hong Kong as well. I believe that the rigidity of the hard core of the Party-state, formed and hardened through its particular type of revolutionary history, its return to the imperial political culture, and its entrenched interest in a total state, makes it impossible for a self-reform to occur.

To sum up, in order to have a less erroneous appraisal of Beijing’s regime, instead of just looking at the appearances of the CCP or its top leaders at the time, we have to have a holistic point of view accompanied by historical and relational approaches. The bright side of my narrative is that the CCP, in the course of its modernising China even further, has also fundamentally changed the initial set of relationships of forces within China. For the past 70 years, all other classes and social groups within China have been at the mercy of this monolithic Party-state. In appearance this remains unchanged, but its actual composition has greatly changed. In addition to this, a big portion of the Chinese upper middle class, the new working class, and those exploited sweatshop workers, are economically connected to the global markets as well. The breaking up of the relationship between China and the United States now puts the Orwellian state to a difficult test, making its situation increasingly fluid. Will a new domestic political force arise out of this fluidity and begin to challenge the hard core of the CCP? That is the riddle of this new stage.

IF: In your book, you also spend considerable energy explaining what the mobilisation was not about. A couple of misconceptions you try to dispel are that the protests were racist, targeting mainland Chinese, and that they were about demanding independence. Why have these ideas taken hold among the public and why should they be rejected?

ALY: First, we must remind ourselves that today’s media corporations are all very powerful in shaping the so-called public opinion. At the beginning of the Revolt last year, when individuals waved the independence flag, other protesters who were not in favour of it would try to convince them to stop by reminding them that the movement was about the five demands, not about independence. In some cases, the persuasion might work. However, both Western media and pro-Beijing media loved focussing on people waving the flag instead—although for quite opposite reasons—ignoring the fact that most protesters did not wave it. This is how a small minority of protesters became emboldened by the media, while the majority, feeling discouraged, chose to remain silent at later protests.

The wonderful thing about this Revolt is that it had hundreds of big and small protests exhibiting great diversity and contradictions. What unified these diverse protests were the five demands, not any other requests. There were only a few protests which were potentially targeting mainland immigrants or visitors here, but they were much smaller in size and also only took place in more remote areas—as such, they cannot represent the movement. But it is also true that most people, who did not approve of the right-wing localists, often chose to remain silent about them. I argue that without an organised progressive force consciously fighting for an inclusive Hong Kong identity, this will continue to be the case, unfortunately.

IF: Finally, you criticise a certain idea that has taken root in some leftist circles in the West: that the Hong Kong protests were right wing and manipulated by foreign imperialists. What is your response to these insinuations?

ALY: Just as the media loves to put a spotlight on protesters waving pro-independent flags, it also loves to do the same to protesters waving pro–US flags. Yet few people are aware that protesters also waved the Catalonian flag, and once held a pro-Catalonian independence rally. Those pro-US forces tried to stop the holding of such a rally because ‘Spain is a US ally’—an argument that was rebutted. This piece of news went largely unnoticed, however.

Last year, I was at a Berlin conference where a participant condemned the movement as being manipulated by the United States by referring to protesters waving the US flag. My response was that her condemnation itself might be seen as manipulated as well, only this time by the media, as she uncritically accepted the media’s preference for the flag-waving minority.

The pan-democrats have always had strong ties to the US and British establishments, but they were marginalised in this most recent Revolt. There were organised pro-US forces, but they were small. The mass movement is led by no one. Most young people waving the US flag did not belong to any political party, they were generally new hands in the social movement and only wanted to call for international support.

That said, the problem with last year’s Revolt was that most protesters did not have any idea of ‘left versus right’, and everything in their world is squeezed into a worldview of ‘either Beijing or us’. For this reason, they just accept any foreigners with some power to help, without ever asking the question ‘are they your real friends?’ This lack of understanding allows protesters to occasionally be depicted as part of the pro-Trump current, which is then magnified by the media.

We must be aware of another facet of this discussion on ‘foreign forces’, though. Western governments, with the United Kingdom and United States at their head, are being recognised as legitimate stakeholders by no one other than the CCP itself, as enshrined in the Basic Law. This law lays down in detail that Hong Kong people would be able to keep their own British law, enjoy the right to the British passport, and even allows foreigners to be employed as civil servants, from the lowest to the highest ranks (except for the very top), including foreign judges, and so on and so forth. This should have given both the United States and United Kingdom a lot of leverage, at least for the remaining 27 years before the Basic Law expires, unless it is further revised. With the Extradition Bill, Beijing did nothing less than break its promise in both the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law. I never endorsed these two documents. Actually, Hong Kong people have always been excluded from negotiations over their fate, but if Beijing wants to decolonise Hong Kong’s colonial legacy, it should replace it with even better protection of human rights, and honour its promise of universal suffrage for the city, not replace it with its own even worse legal system or annihilate the city’s autonomy. If the US government is not our real friend, right now Beijing is our real enemy. That is what matters.

IF: In the book, you explain how the youth have played a fundamental role in the mobilisation. What makes the ‘1997 generation’ so different from those who came before?

ALY: Now Beijing wants to take full control of Hong Kong’s education to make sure the young would not be influenced by dangerous ideas. This is laughable, and actually counterproductive. I was a secondary school teacher for nearly 20 years. I failed terribly in trying to instil a spirit of rebellion against the colonial education among my students. The time simply had not come yet. Only with the coming of the ‘1997 generation’ did a significant section of society begin to stir.

It is a generation that is full of anger and hope. They are angry because they felt lied to by Beijing. Since their birth, they have been hearing about Hong Kong people challenging Beijing to honour its promise of universal suffrage. As they grew up, the suffrage was nowhere to be seen, and Beijing launched wave after wave of attacks on Hong Kong’s autonomy, hence the anger. On the other hand, they think there is still hope, if only they are radical—or at least more radical than the pan-democrats. A new way of fighting back must be found, and they found it ‘by any means necessary’, by ‘being water’, ‘being brave’, etc. If civil disobedience and occupying major streets in 2014 were not enough to make Beijing yield, then let us fight the police and occupy the legislature! Their bravery also came from their ‘end game’ mentality—this will be our last struggle for our autonomy so let’s spare no effort!

Another factor at play was the relative liberties the new generation enjoyed while growing up. Under British colonial rule, our generation grew up in quite a repressive atmosphere and learned to be apolitical to avoid trouble. Hence the 30-year-old democratic movement was always very timid, so you see how different the new generation is from the old. The young were inexperienced, but this also enabled them to think outside the box of the pan-democrats. Now they have seen with their own eyes that even a revolt as massive as last year’s did not make Beijing yield to them; on the contrary the latter now retaliated with an even more lethal weapon, the National Security Law. The young now finally understand that it is going to be a very long struggle, and there is no such thing as an ‘end game’. It is going to be a very hard fight as well, because Beijing’s agenda is to destroy this generation. They did it before, in 1989.

To sum up, one may say that the contribution of the young is that they, like the boy who pointed out loudly that ‘the emperor has no clothes on!’, were able to identify where the real problem lies. They also tried to fix it, even if events proved that it was a task for which they were not yet fully prepared.

IF: We recently published an article by Anita Chan about the extraordinary mushrooming of trade unions in Hong Kong over the past year. You also dedicate part of your book to this phenomenon. Can you please delve a bit more into the role of the workers during the protests? What are the prospects for this nascent labour movement under the New Security Law?

ALY: If one compares last year’s Revolt with the Umbrella Movement then one witnesses a step forward for labour. The pro-democracy Confederation of Trade Unions (CTU) was founded in 1990 and nowadays it claims to have 95 affiliated unions representing 190,000 members. It always follows the pan-democrats’ political line and this eventually alienated the young generation, which is one of the reasons why it played nearly no role at all during the Umbrella Movement. It called for a strike, but I used to say that only two and a half unions heeded the call, because the teachers’ union was only half-hearted about it. It was a reflection of the fundamental weakness of the labour movement in Hong Kong at that time. Last year, when the movement had just begun in early June and right after the two-million-strong march, the CTU called for another strike but was unsuccessful. History seemed to be repeating itself. But no, the young did not allow that. The following months saw an ever-stronger mobilisation, but the young were increasingly aware that they alone would not be able to make Beijing yield, so they repeatedly called for a general strike.

This was also the moment when a new segment of young employees began to emerge as activists. Together with the CTU, the allied forces were able to call a successful general strike, for the first time in many decades, on 5 August 2019. Among others, pilots and flights attendants responded en masse, and half of all flights were grounded, leaving air traffic in chaos. Although later strike calls were unsuccessful after Beijing retaliated by forcing Cathay Pacific to sack a few dozen of its strikers, the August strike went into the memory of many as a proof of the power of labour. This also laid the foundation for a new union movement where dozens of new unions were founded. The spread of the Covid-19 pandemic gave a chance to the newly founded Hospital Authority Employee Union to test its strength. The union accounts for 20 percent of the workforce of 80,000, and in February 2020 it went on strike for five days to demand that the government temporarily close the borders between Hong Kong and mainland China to stop the pandemic from spreading further in the city. The upside of this strike is that one witnessed that the new leadership has the guts to fight, which is very rare among local trade unions. The downside, though, is that on several occasions it seemed that the membership was not ready to take a more militant line.

With Beijing retaliating with its National Security Law, this new union movement now faces the greatest challenge since its founding. Unions may not be Beijing’s top target, but the mainland authorities definitely dislike a militant union movement. I hope that the young unionists will have enough time to consolidate themselves before Beijing starts its next offensive.

IF: One aspect that I don’t find mentioned often in media coverage is how the National Security Law will likely impact civil society on the mainland. For three decades, Hong Kong has been the funding gateway for a wide array of civil society organisations in mainland China, including labour NGOs, human rights lawyers, and other kinds of activist groups. With Chinese civil society already under unprecedented assault, will Hong Kong still be able to play such a role?

ALY: Right now, it is already very difficult. Some Hong Kong groups that have been supporting Chinese labour have had to either shut down their operations or significantly scale down and lay low. The more severe the economic crisis and the more the conflict with the United States is escalated, the more likely Beijing will be to seek the total obliteration of labour groups in the mainland, especially those with ties to Hong Kong. I remember a dozen years ago we rented a bus in Shenzhen and took a whole bunch of German grassroots labour activists to visit factories where strikes had occurred. We did not dare step outside the bus though, but the German activists were still impressed with the stories we told and happy about being able to see the factories. This is unimaginable today. The narrow but real space for NGO activism in the Pearl River Delta is long gone.

We still have another form of leverage, however. For decades, the picture of Hong Kong people standing up for their rights has inspired many in the mainland. In this new period of repression, Hong Kong could still promote a movement from below in the mainland in an indirect way, i.e. through its own struggle for autonomy and democracy. This is important as Hong Kong’s advantage lies in its ‘soft power’ rather than the non-existent ‘sharp power’ which certain ‘braves’ were looking for. Making the city unwelcoming to mainland Chinese is suicidal. Unfortunately, in last year’s Revolt, Beijing made full use of the right-wing localists’ presence to depict the whole Revolt as being about independence and China-bashing, not to mention pro-Trump. This alienated potential mainland allies. The problem for Hong Kong lies less in the existence of right-wing localists, however, and more in the lack of a strong labour left wing, which, if present, could put the right wing under check. The good news is that with the new trade union movement there is now a whole new group of labour activists to win over to a labour left wing, although it will take time.

Secondly, the seeds sown by mainland and Hong Kong labour activists in the past two decades will continue to grow in the future. Twenty years ago, most rural migrant workers did not have any idea of their legitimate rights. Through their own struggle, plus some help from NGOs, today many of them are much more informed and ready to demand their rights. In 2018, for instance, more than a hundred silicosis victims from Hunan spontaneously organised to go to Shenzhen (where they had contracted the occupational disease while working) to petition for compensation. Under harsh repression, workers cannot do any long-term organising, but through these kinds of defensive struggles they are still able to be partially empowered.

IF: What comes next for the people of Hong Kong? What venues are left for those who live abroad to express solidarity?

ALY: Since you sent me these questions, the Hong Kong situation has been further worsening, day by day. The absolute asymmetry of power between Beijing and Hong Kong implies that we will be in a dire situation for years to come, unless the mainland situation takes a surprising change of direction. Some protesters are now celebrating the success of their so called scorched earth tactic after the United States nullified Hong Kong’s special status. I don’t subscribe to their idea of ‘success’ because turning Hong Kong into a battlefield between Beijing and Washington is going to make things worse, not easier. I do not intend to place too much blame on these ‘scorched earth’ advocates though, as from the very beginning Hong Kong has been too small to play any leading role in shaping its own fate. Sadly, its fate is always determined by outside forces. No matter how flawless our resistance, once Beijing makes up its mind to finish our autonomy, we are done in this regard. Daily resistance to stop things worsening is still necessary, but we have to prepare for the day when organised opposition will be barred from elections altogether if not totally wiped out. Local people are aware of this coming catastrophe and are hence looking forward to more international support. However, as a small city this may also imply that the fight to defend our autonomy has slipped away from our own hands.

Precisely because of Hong Kong’s uniqueness—small but significant in its geopolitics and international finance status—international pressure is vital for us. But it has to be the right kind of pressure. We all know too well that governments are more an establishment force than an engine for progressive changes. It is just too dangerous to leave the solidarity campaign with Mainland and Hong Kong democratic movements to foreign governments alone, not to mention ceding it to Trump. We need international progressive labour and civil associations and individuals to press their governments to do the right things while stopping them from doing wrong things. The prerequisite of this endeavour is to grasp the actual situation going on here. My suggestion is that we should be guided less by ideology and more by objective investigation and simple empathy—and here I mean ideology in the sense of a ‘socially necessary illusion’ which is divorced from reality. What unified the massive movement was the five demands, with four related to the opposition to the Extradition Bill, the fifth being universal suffrage. How can anyone who claims to be left or progressive not support these demands?

No comments:

Post a Comment