When asked how he's doing, the writer Rudy Wurlitzer has a handful of standard responses: "I'm tap-dancing on a rubber raft," he'll say, or "I'm still on this side of the grass," or "I'm stretched out in front of the Trail's End Saloon, staring into the big empty." Maybe he believes that. But to an outside observer he would seem, at 78, to be faring pretty well. His hips and knees are periodically attacked by surgeons, so he walks with a limp, but he's got the handsomeness of an elder statesman and a perverse mind working at its peak.

He was "crouching in a corner" when I visited him at his grand Victorian home in Hudson, New York, last summer. The walls there are lined with the work of his wife, the photographer Lynn Davis—pictures of ancient Egyptian and Cambodian temples, icebergs and waterfalls, monuments eaten up by time and the elements. Wurlitzer carries himself quietly and with a genuine humility. "Who cares what I've got to say? Who wants to hear it?" he said when first approached about being interviewed. "I think I'd rather just crawl under a rock." Cinefamily had just made inquiries to Wurlitzer about mounting retrospectives in Los Angeles and New York of the films he wrote in the 1970s and 80s—road movies, westerns, and unclassifiable metaphysical excursions—and he seemed deeply ambivalent.

When I asked him whether he was going to go through with it, he crossed and uncrossed his legs, shifted in his seat, shook his head, and looked pained. "I can't. I just can't do it." He trailed off for almost half a minute. "I just can't look at the old work. It makes me feel all kinds of things. It embarrasses me. It makes me anxious. It's not worth it at this age, physically or emotionally. That's why I don't really like doing interviews anymore. I'm always aware that there's so much on either side of the past, and I just want to stay in the present. Especially as I get older."

Since the late 1960s, Wurlitzer has been a screenwriter. If you've seen Two-Lane Blacktop or Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid or Walker, you've seen his work. None of the films he wrote raked in box-office millions, and many screenplays he's written have gone unproduced. But he enjoys a reputation that makes people speak about him in superlatives—that he's one of a kind, that he's his own genre, that there's no one, no one, quite like him. His work makes people want to mount retrospectives on both coasts.

Wurlitzer is also what's best described as a cult novelist. Fiction launched his screenwriting career, which in turn sustained him as he wrote four more experimental novels and a memoir. His novels came into the world quietly and then disappeared the same way. But they insist on keeping themselves alive, being reissued several times and each one having its devotees.

Director Robert Downey Sr., who speaks with Wurlitzer almost daily, told me, "He's so unique, it's hard to analyze him. That writing is tight. It's absurd. It's everything. Those first three books will be around for a long time. And there's no genre there. But they are all absolutely out of one person's brain."

Composer Philip Glass, a friend of Wurlitzer's since they were both 17, said, "I've worked with a lot of other writers, but he's the best. I really wanted to get him into working in theater because he knew how to write for movies so well. He's able to give you clear, verbal resolution of an idea without too many words, and his language is really a vernacular language, the language of everyday words. I think of him as a quintessentially American writer—just the clarity of his writing, the economy of it, the rigor of it."

Wurlitzer is a quiet legend who worked elbow to elbow with louder legends. He worked and made for the sake of working and making and never got very craven about the reward. He was, he says often, grateful to be surviving. Once, on the phone, he told me a story that got at the essence of how he carried himself through his life and work and why his name isn't spoken with the frequency and volume of some of his contemporaries'.

"I revered Samuel Beckett," he said. "I was living in Paris in the early 60s. I was just a young dude on the drift. And I knew Beckett would come to this one café at a certain time. I would take a position in view of his table, and he'd sit there with his drink, and eventually Alberto Giacometti would come in and they'd nod to each other, and Giacometti would sit down and have a drink too. They would not say one word to each other, and then they'd get up, shake hands, and go on their way. I was so impressed by that. What an amazing communication they must have. That almost made me tremble to watch them. I never introduced myself to Beckett, though. I just couldn't. I didn't want to bother him."

Wurlitzer was born in Cincinnati in 1937 and grew up in New York City at the tail end of the Depression and during wartime deprivations. His family subsisted in a sort of ruined privilege. Wurlitzer's grandfather had amassed a fortune making musical instruments, but most of that was gone by the time Rudy arrived. His father had a name as a dealer of stringed instruments and owned a store in midtown Manhattan. Wurlitzer had musical training from the beginning. "When I was born," he told me, "my grandfather and father put a miniature violin in my crib. So I was fucked." His father would sometimes entertain visitors like violinist Jascha Heifetz, and Rudy was always asked to play. His response was usually to try to run away.

As he got older, he ran farther and farther: to an oil tanker that sailed the Mediterranean; away from his Columbia University education to Cuba, just as Castro's troops entered a euphoric and jubilant Havana; into the Army; to Paris and Majorca; and finally back home to New York City in 1964, where he took an apartment in the East Village.

By the time Wurlitzer settled downtown, the country's cultural weather was becoming curious. There was a rising pitch of activity in Vietnam, greater turbulence in the civil rights battle, and post-Beat acid consciousness beginning to wash in from the West Coast along with the interest in Eastern beliefs that attended it. In the East Village the streets were mounded with garbage, and living there involved genuine bodily risk, but the scene was thriving.

Wurlitzer and his friends spent long nights in the Cedar Tavern, cigarettes between their fingers, drinking and arguing about music and writing and art. There were performances and happenings to witness in lofts and galleries. They'd see Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman at the Five Spot Café, or John Coltrane at the Village Vanguard. Bob Dylan was putting on his dandified, surrealist speed-freak persona, and no one was oblivious to the energies he unleashed.

"In the days when I was being formed in New York there was great permission. It was a very different time in that way," Wurlitzer told me. "There were people like [Claes] Oldenburg and [Robert] Rauschenberg. You were rubbing up against people like Jasper Johns and certain musicians. An early friend of mine whom I spent a lot of time with was Philip Glass, who was trying to break down the orthodoxy of music. John Cage was a big figure for me because he enlisted silence in his work and I found it very moving."

And there were other methods to help blast at orthodoxies. "Drugs were definitely in the room, and I tried everything," he said. "A lot of drugs I couldn't do. Cocaine made me crazy—I couldn't do that. I could smoke dope. I took acid until I didn't think there was any more to learn from it. Ayahuasca. Mushrooms. I touched base, but—I don't know—I didn't really do it that much."

Wurlitzer had been writing since high school. One of his journal entries from 1955 reads: "I will use this journal to practice writing. I will be able to develop a style or even find out if I have any talent." While he was living by himself in a 12th Street tenement, he began working on the story of a man in ownership of three memories and a fake octopus in a tank, wandering along the California coast. The Paris Review published it in 1966, and Wurlitzer expanded it into the novel Nog, published by Random House in 1969.

Nog is a laying bare of consciousness. The book pulls back the scalp and chips away the bone to show the neurons and nerves of the human mind twitching and pulsing in new air. The whole book is a may-or-may-not proposition: There may or may not be a character named Nog, and Nog may or may not be the narrator himself; one event or other may or may not have happened; other characters may or may not be inventions of the narrator. There's no plot, only movement and motion. Past and present tenses shift constantly in the same paragraph and even sentence; one sentence makes a statement only to be negated in the next. One representative passage reads:

I am too comfortable sitting on the sand, my foot drying now, not knowing that I am about to move on. The storm wasn't invented. I'm sure of that. And the sea was cold and even wet. That was two or three days ago. But there must be another place, a replacement, one foot having the problem of following the other foot, to another place. Now that there are no other feet to follow. I stood and sat again. I must be holding back.

A certain utopian optimism still held as the 60s drew to a close. But in 1968, Wurlitzer had tuned into a quiet-but-getting-louder signal broadcast by people like the Diggers in San Francisco and the Motherfuckers in New York City, something harder-edged and a little more aggressive, possessed of a violent streak that was rapping at the crash-pad windows. The atmosphere of Nog is bleary and broken. Events are neither good nor bad, helpful nor damaging; they only are. It's a sort of Zen trip toward the Altamont frontier.

"My obsession was to explore the composition of the self and what's real and what isn't real. Which is an ongoing process. With Nog I was trying to take it through that whole process. It was the opposite of a screenplay, where it's linear and there's a beginning, middle, and end," Wurlitzer said. "That's the way my mind was working. I was just starting out with no external—no one telling me what to do. I just explored where my mind was. It wasn't conceptual. It was intuitive. It was done for its own sake.

"The frontier that I'm involved with is an interior frontier," he continued. "Not to be too pretentious, but it's about exploring the non-duality of form and emptiness. Which is about what happens when you dissolve your inevitable self-absorptions and are left with the present. You realize that the past is just like everything else—it's a dream. And it's just as much of a fiction as if you were actually writing fiction and we choose to say or choose to remember or can't remember how to remember whatever it was you were trying to remember. It comes out filtered and redefined and has an envelope of fiction to it. Because we're all basically fiction."

Out in Hollywood, in 1970, director Monte Hellman was preparing to begin work on Two-Lane Blacktop. Hellman, a protégé of C-movie impresario Roger Corman, hated the shooting script, about a cross-country auto race, and loved Nog. He pretty soon made an easy leap of logic, and one day Wurlitzer's phone rang in New York with an offer to go to LA and rewrite the screenplay. Wurlitzer took a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont, and as the Manson trial was about to start and the blood was still wet on the campus of Kent State, he began writing. Wurlitzer knew absolutely nothing about cars but read as many hot-rod magazines as he could find and hung out for a time with some stoner gearheads in the San Fernando Valley.

The result was a very peculiar and existentially torqued road movie. Starring James Taylor as the hyper-intense Driver, and Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson as the Mechanic, Two-Lane follows the men as they race GTO, played by Warren Oates, across the country. Very little happens, and there's very little spoken. The colors are stunning, the landscape is beautiful, and the beginning and endpoints don't matter. The important thing is the moment, the motion, and the pure act of driving. We're given nothing of anyone's history, and what little we do get is all lies. We're also given fine lines like:

THE MECHANIC: You'd have yourself a real street sweeper here if you put a little work into it.

GTO: I go fast enough.

THE DRIVER: You can never go fast enough.

Esquire called it the movie of the year and published the screenplay in its entirety in April 1971. Wurlitzer suddenly found himself with a lot of cachet.

Two years before Wurlitzer began his Hollywood residency, the old studios were in serious decline. Run mostly by men born in the late 1800s, they churned out failure after failure with no sense of what moviegoers might best respond to. Until, of course, Easy Rider was released by Columbia in July 1969. Directed by Dennis Hopper and starring Hopper, Jack Nicholson, and Peter Fonda, Easy Rider was shot for around $400,000—and to everyone's shock grossed millions upon millions of dollars. More important, the other studios clamored to give anyone tuned into the counterculture a chance to write and direct and—they hoped—duplicate Easy Rider's success.

That was the atmosphere Wurlitzer arrived in, and as he wrote his second novel, Flats, upon completing his work on Two-Lane, he embraced it. He became close friends with people like Hal Ashby, Nicholson, and Downey. There were days full of writing and networking and long—very long—nights of carousing. Beyond Hollywood, the Weather Underground couldn't stop blowing things up, and the pace of action in Vietnam got even quicker, but the bacchanalian textures of movie life in Los Angeles kept begging to be touched.

Of course, the magic couldn't persist. The American auteurs might have started with the studios' benediction, but personal, searching, visionary films lost their draw, and their makers lost their cachet. Wurlitzer had, in fact, already gotten a feel for the direction things would take.

After the success of Easy Rider, Hopper leveraged his clout to make a film in Peru, and in the glow of approbation for Two-Lane's script, Wurlitzer cashed in on his. He persuaded Universal to let him direct a film set in India and traveled there in 1971 with some producers and moneymen to scout locations. While Wurlitzer was overseas, Hopper's film was released. Appropriately titled The Last Movie, it was an artistic and financial fiasco, every frame of it smeared with drugs. Panic tremors ran through the studio corridors. Permissions were rescinded and productions canceled. Wurlitzer was one of the casualties. Universal pulled the plug.

Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote once about what he termed the "acid western," saying that in most westerns "there's a movement toward enlightenment and freedom," whereas the acid westerns journey toward death. Acid westerns, according to Rosenbaum, "are revisionist Westerns in which American history is reinterpreted to make room for peyote visions and related hallucinogenic experiences, LSD trips in particular." Wurlitzer, he wrote, "is surely the individual most responsible for exploring this genre, having practically invented it himself in the late 60s and then helped to nurture it in the scripts of others."

Wurlitzer's next project would be a prototypical acid western, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, directed by Sam Peckinpah, financed by MGM, and featuring Bob Dylan among the cast. One of Pat Garrett's producers, Gordon Carroll, approached Wurlitzer about doing the screenplay. Peckinpah was a Two-Lane fan, and he and Carroll agreed that Wurlitzer could do justice to the film Peckinpah wanted to make: the sort of exploration of killing men and their personal codes and betrayals that Akira Kurosawa might have undertaken, an even more philosophical journey than Peckinpah's 1969 success, The Wild Bunch.

MGM was struggling financially when production began in 1972. The studio had made a cripplingly big investment in Las Vegas casinos and hoped that Peckinpah's film might put money back in the coffers in time for a late-summer shareholders' meeting. To hedge their bets, MGM gave Peckinpah 70 days to shoot, not much longer to edit, and cut every budgetary corner it could.

"Peckinpah was very much an ingrained and revered outlaw in his way. But that film was what made him so extraordinary," Wurlitzer said. "Peckinpah was constantly at war with the powers that be, with the studio, with the money people. He loved the war, and those who were around him got the benefit of that."

The Pat Garrett set was chaos. To counteract the pressure, Peckinpah drank on scale with his ambitions. He was demanding more and more rewrites from Wurlitzer. After shooting finally finished, MGM used one of Peckinpah's work prints to assemble a cut of its own, 17 minutes shorter than the director's edit. Peckinpah demanded his name be taken off it, and MGM refused. The film was a mess and a flop. Wurlitzer reeled at what the studio had done and recoiled from the new attitudes that were palling the industry. He flew to Nova Scotia and wrote Quake, a novel set after an earthquake has reduced LA to ruins. It was a close look at the evil that men do in an atmosphere of lawlessness. It was also Wurlitzer's middle finger to Hollywood. He left town and never really went back. He'd work on films for years to come, but not theirs.

On a summer afternoon in 1977, when Star Wars was breaking every cinematic record, Wurlitzer was driving on Route 85 in New Mexico, cutting through the flats and scrub and sand with Albuquerque at his back and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains humped up ahead. He came along a line of trailers and trucks loaded down with cameras and lights. When he saw teams of people around the vehicles, he slowed down to look and recognized the faces of bit-part players and crew members he'd known five years prior when he'd worked on Pat Garrett.

He stopped the car and stepped out into wicked heat and a zealous sun. He spoke with friends and acquaintances and discovered this was the production for Peckinpah's latest film, Convoy, a cocaine- and liquor-fueled romp involving truckers, cops, and CB radios.

Wurlitzer made for Peckinpah's trailer, rapped on the door, and walked inside.

Sam Peckinpah lay naked on a bed attended by a beautiful, semi-clad nurse who was ramming a shot of vitamin B12 into his ass with one hand and giving him a reach-around with the other. Peckinpah stared at Wurlitzer for a second, then reached over to a side table and picked up a pistol and leveled it at Rudy.

"Where the fuck have you been?" said Peckinpah. Then he passed out.

"Where was I and what was I doing in those years?" Wurlitzer writes in his memoir, Hard Travel to Sacred Places. "Writing a book, a few film scripts in between a failed love affair, hiding out in New Mexico, studying Dharma in Nepal, surviving in New York. Drugs, sex, and rock 'n' roll. Trying to meditate. I can't remember the lineup."

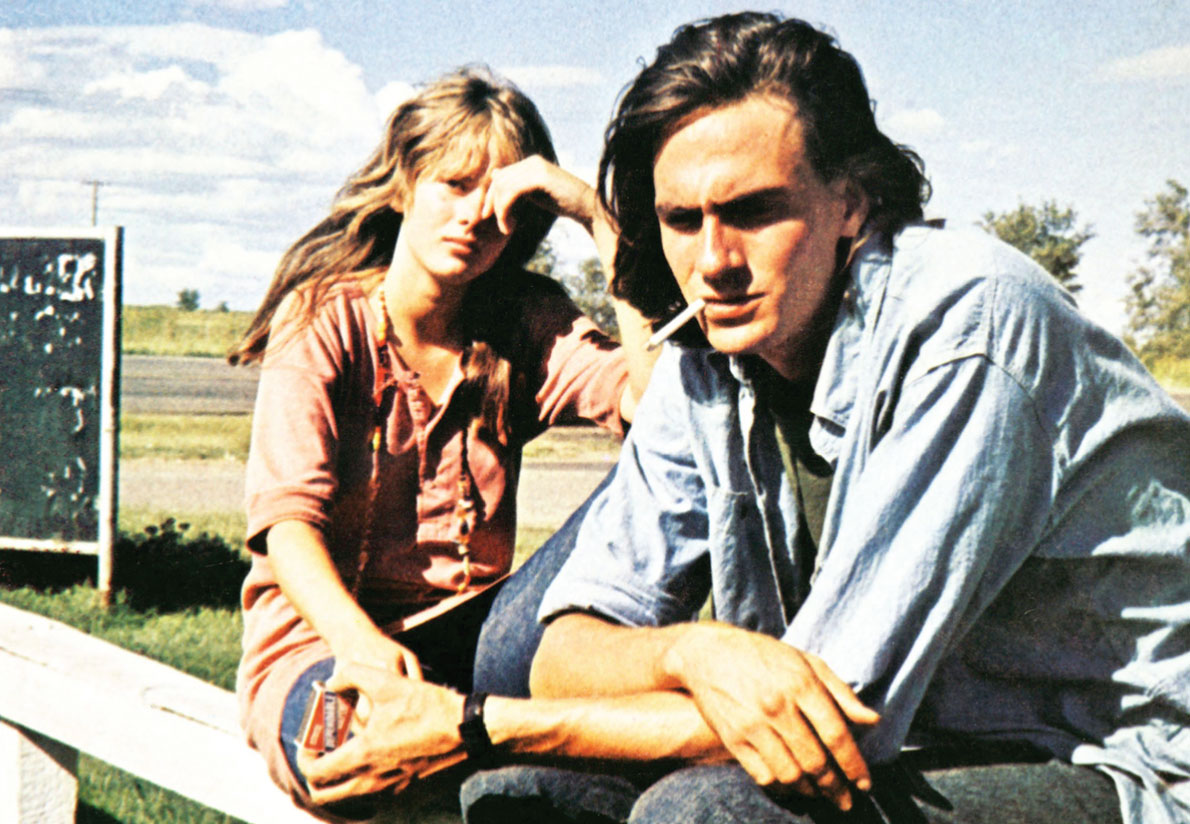

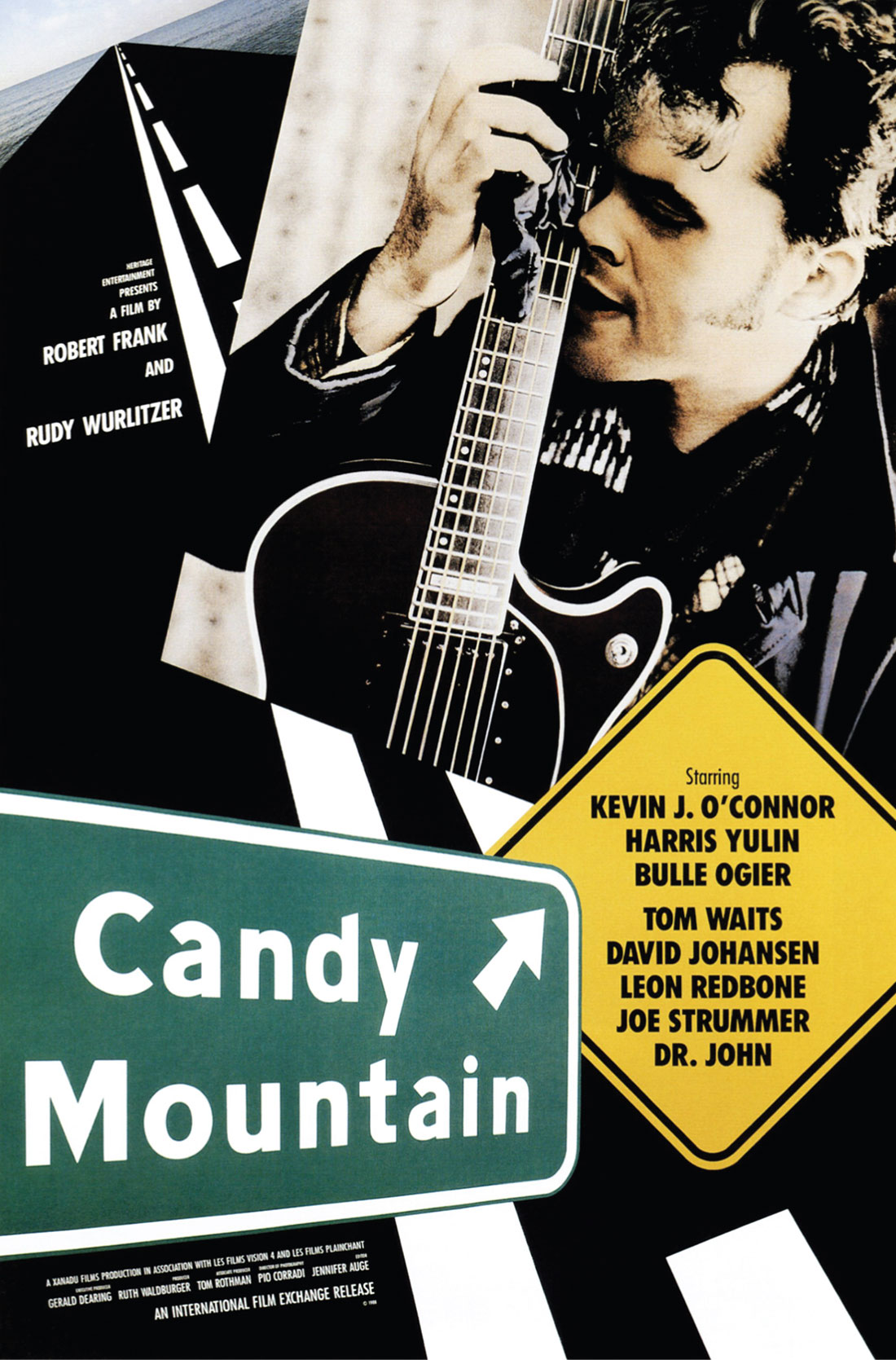

In 1984 Wurlitzer published another novel, Slow Fade, and penned a series of scripts with Alex Cox, who wrote Repo Man and Sid and Nancy. Among these was the 1987 film Walker, a surreal, bloody biopic about William Walker, the 19th-century despot of Nicaragua. The next year, Wurlitzer and photographer Robert Frank co-directed Candy Mountain, another insane road movie. Wurlitzer went on to write scripts for Bernardo Bertolucci, Michelangelo Antonioni, and a few other European directors. He penned two libretti for Philip Glass and wrote Hard Travel to Sacred Places, a memoir about Buddhism and the extraordinary grief he experienced when Lynn Davis's son and his stepson, Ayrev, died in a car accident.

"I kept busy," Wurlitzer said. "I was lucky in that I got to pick and choose what I wanted to work on. I needed to put coin on the table. It was getting more and more impossible. But eventually, I found it necessary to get rid of my movie agent in LA. Not because he wasn't doing enough—but because I was afraid I'd be offered something terrible and I wouldn't have the courage not to do it."

There was one project that wasn't a matter of picking and choosing. Starting around 1984 or 1985, Wurlitzer wrote a screenplay called Zebulon, a particularly wild acid western involving a fur trapper, Zebulon Shook, who suffers a curse causing him, after being shot, to wander in limbo between the worlds of the living and the dead. He takes a mess of bodies with him on his drift. He connects with, departs from, and meets again family members and fellow outlaws and random passersby, all the while pursued by psychopaths angling for the bounty on his head. In the end, he's sent deathward into the Pacific, lying in a dugout canoe.

Hal Ashby wanted to tackle it, but it didn't get on. Alex Cox came close, even getting Richard Gere to give a verbal commitment, but Gere bowed out and the financing never shook down. Jim Jarmusch, who traveled in some of the same New York City circles as Wurlitzer, got his hands on the screenplay and initiated a series of conversations and meetings. Together, they parsed the script and speculated on the story until their differences in opinion overbalanced their agreements. They shook hands and took an amicable leave of each other.

A couple of years later, in 1995, Jarmusch released Dead Man, starring Johnny Depp and a fantastic Neil Young soundtrack, about a man cursed to wander between the worlds of the living and the dead after being shot. He takes a mess of bodies with him on his drift, pursued all the while by psychopaths, and is finally sent into the Pacific to die lying in a dugout canoe. Wurlitzer wasn't involved or credited.

"He should have sued," said Cox. "I would have. Even studios don't operate that way."

Wurlitzer opted against it. Too toxic, he thought. Mostly, Wurlitzer said, more than any consideration of cash and credit, he was saddened that a friendship had ended.

"I read Zebulon, and I'd read a lot of scripts at that point in my life," said Lana Griffin, an editor, script consultant, and longtime friend of Wurlitzer's. "It was the best script I'd ever read. I was shocked. It shook me to the core because I thought, If that hasn't been made…"

The screenplay kept making the rounds, but Dead Man had made it a long shot. Finally, in the mid 2000s, Wurlitzer told Griffin that if Zebulon were ever going to see the light of day, it would have to be as a book. For the next few years he worked on his fifth novel, The Drop Edge of Yonder, which the Two Dollar Radio imprint published in 2008.

"I think Rudy is in a class of his own. People who engage with his work are so affected by it because not only is he writing about a journey, an interior journey, but he takes the reader on that journey successfully," Griffin told me. "It's successful in terms of being an entertaining read and, at the same time, sending you on your own journey into your unconscious. He always says he writes to know what he's thinking. He's always in process and it's always being discovered, and therefore it's very free."

I've never been able to not think of Wurlitzer as one of the last few of a heroic group still standing, people who changed the tenor of our creative culture. With publishing still caught in a confused state of transition, a recording industry in stunned collapse, a coprophagic colossus of a motion picture industry—and that's not even talking yet about the worlds of art and theater—the impulse to do anything creative seems as insignificant as pissing in the ocean.

And that Wurlitzer isn't quite done in this climate, that he won't ultimately admit defeat, that he would write to ensure that his vision, Zebulon, would arrive somehow and somewhere out in the world makes him heroic still.

A week after I met Wurlitzer at his home in Hudson, he called me up on the phone and asked me to come back. "I feel like I maybe have more to say, or at least ways to say what I said better," he told me.

The next afternoon, I was back with Wurlitzer in Davis's studio. He was talking at length about being an artist. It was part musing, part requiem, but it also had more than a hint of challenge. "I think that now more than ever the megacities are getting to be more and more impossible hell-worlds," he told me. "I mean not just how much it costs to live in LA or New York or wherever. The confusion, the distractions, there's no sense of community. People who can have a small sense of community and feed each other that way and be spontaneous and have a relationship that's about one to one rather than being plugged in is more and more important. And I think that will grow, because I think it's the only way to survive."

He had been agonizing too over a cold email he had received that morning. "He got the address from my website, I guess, and there was just one line: 'Dear Mr. Wurlitzer, I'm a big fan of your work. Can you tell me what I should do to become a writer?'" he told me. "And I haven't answered him back yet. I don't know—get a day job and maybe think about trying to use your hands? Maybe pick up waiting [tables] or something? Be careful? I don't know what kind of advice to give. I mean, just the thought of what it means to become a writer now and face the commercial aspects of it, what it means to survive… I don't have the answer. I don't know where it's going. So I don't know how to respond to him. I guess maybe plant your ass in a chair and write. And pray for endurance."

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment