MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI: THE PLAYBOY INTERVIEW (1967)

by Curtis Pepper

As the creator of such meticulously crafted and psychologically penetrating films as L‘Avventura, Red Desert and Blow-Up, 55-year-old Michelangelo Antonioni has earned a lofty but controversial niche among cinematic chroniclers of the problems that beset modern man. With an intellectual’s detachment and a prophet’s conviction, he has explored the alienation of man in a depersonalized world the fragility and ambivalence of his emotions and, above all, the impermanence of his love. Gaunt as a Giacometti sculpture, Antonioni himself presents a mask to the world. He claims to have little interest in material rewards, still less in critical acclaim or abuse; but he is no stranger to affluence—nor to the world of spiritually bankrupt overprivilege inhabited by his lonely characters.

The son of a successful industrialist, he grew up in the quiet Po Valley city of Ferrara, winning regional tennis championships and earning a degree in economics and commerce. But he was already incubating a personal rebellion against provincial, middle-class merchant life and a passion for the cinema that inspired a pilgrimage to Rome. After gaining some experience as a film critic, he attended the Rome Experimental Film Center, selling his tennis trophies to keep from starving, until finally he began to meet and work with the directors who were making names for themselves—Roberto (Open City) Rossellini, Giuseppe (Bitter Rice) De Santis and Federico (The White Sheik) Fellini, among others. After a term of military service, abbreviated by the liberation of Rome, Antonioni launched his career as a director with a series of striking documentaries, which led to his first feature, Cronaca di un Amore in 1950. Dissatisfied with the earthy sociological approach of neorealism, Antonioni here preoccupied himself with the ways in which external reality shapes—and warps—the psyche, producing a haunting and poetic film that the critics promptly characterized as “interior neorealism.” Set amid post-War Milanese high society, it detailed the collapse of an extramarital romance, destroyed by guilt after the woman’s husband—who had been marked for murder by the conniving couple— unexpectedly dies.

Thus began Antonioni’s somber psychoanalysis of 20th Century life, in all its complexity and anonymity. His succeeding films were suffused with a deepening fatalism. Self-destruction was the theme and denouement of both Le Amiche, which Antonioni made in 1955, and Il Grido, completed two years later. Against the background of industrial Turin, Le Amicheilluminated the stilted and superficial lives of a clique of wealthy women who toy with one another’s deepest emotions until one of them finally commits suicide. In Il Grido an itinerant mechanic fathers a child by a married woman; when she rejects him after the death of her husband, he searches, with his daughter, for a new life; frustrated at every turn, he eventually throws himself off a water tower. The film paints an insightful but desolate picture of man in the Machine Age, rendered weak and rootless by the impersonality of his environment.

But the film that marks Antonioni’s coming of age as a director is L’Avventura (1960), the first of a cynical series about love among the affluent. It begins with the disappearance of a wealthy Roman girl whose lover, Sandro, and best friend, Claudia, begin a frenzied search for her. Soon they are lovers, however, and the missing girl is forgotten. But as they wander through the pleasure-filled world of Riviera resorts, Sandro pauses to accept the wares of a prostitute. Discovered by Claudia, he can only protest his frailty; to absolve herself of guilt for her own betrayal—of her lost friend—she resignedly forgives him. Thus fidelity and love itself have succumbed to ennui.

The next film in the series, La Notte, covers a day in the life of a long-married and still affectionate but loveless—couple. Giovanni, a successful novelist, circulates in the world of Milanese culture; Lidia, disillusioned by his ebbing spiritual resources, accompanies him on a visit to a dying friend, to a publication-day cocktail party, then takes a lonely walk through the places where they once lived, searching for time past. That evening, they go—separately—to a marathon party given by a wealthy industrialist, where Giovanni makes a halfhearted attempt to seduce the host’s beautiful daughter. Toward dawn, Lidia scornfully confronts him with a passionate letter he had written to her years before. Ignoring the letter’s implication —that he has since become emotionally, if not sexually, impotent—he makes love to her, but with a chilling new realization of his own psychic isolation. Marriage has kept them united in body but not in spirit, and their only reason for staying together is knowledge of each other’s needs.

If lovers are doomed to infidelity and if marriage must lose its meaning, is there value in any human contact? L’Eclisse, Antonioni’s next film, answered this question with a sobering portrayal of a young woman’s melancholy conclusion, after two unsatisfactory affairs, that men are islands and that true communication is impossible; attempts at constancy in love only hasten its demise. Antonioni ended the picture with a remarkable silent sequence, seven minutes long, in which the camera explores the streets and buildings of a futuristic Roman suburb—a stark symbol of a bleak and sterile hereafter.

Antonioni’s first color film, the subtly shaded Red Desert, concerns the futile search of a woman, whose husband is too preoccupied to care about her, for reassurance in the arms of another man. After this self-diminishing transgression, she wanders aboard a ship and explains to a sailor she happens to encounter, in an extended soliloquy, that she must return to face the responsibilities of her life. Despite the tragic tone of the ending, Antonioni seemed to be saying that acceptance and flexibility are the keys to survival in a shallow, shifting world.

Having dissected—and interred—Italy’s “decadent’’ middle class, Antonioni was restless for a change of scene. A visit with Monica Vitti in England two years ago exposed him to “swinging London” where youth was radically recasting Britain’s stuffy pipe-and-slippers image. The result was Blow-Up, a film that dazzled and shocked both critics and audiences around the world. The protagonist is a successful young fashion photographer who occasionally sallies from the pop op fantasy world of his studio to go slumming for socially pertinent candid shots in the “real” world. While enlarging prints of a couple in a public park, he suddenly discovers that he has recorded what seems to be evidence of a murder. But when he seeks counsel from his pot-smoking friends, he finds that to them the murder of a stranger is totally insignificant. Dejectedly wandering through the park—after discovering that the body has been spirited away—the photographer meets a group of students, their faces painted white, who are playing tennis with an imaginary ball. He joins their game. Moral: Reality is what one chooses to believe is real.

In projecting this personal reality on the screen, Antonioni has discarded the standard film clichés, striving instead for the sleek, uncluttered look, the unfettered flow of action, the almost ascetically understated dialog and emotions that are essential to his cerebral cinematic style. While this unique “grammar” of the cinema, like his dark thematic preoccupations, has always been controversial, critical debate has never been more animated—or divided—than over the “meaning’’ of Blow-Up, why he chose to shoot it in English and in London and why its mood of passionless abandon is in such sharp contrast to his earlier, more somber works.

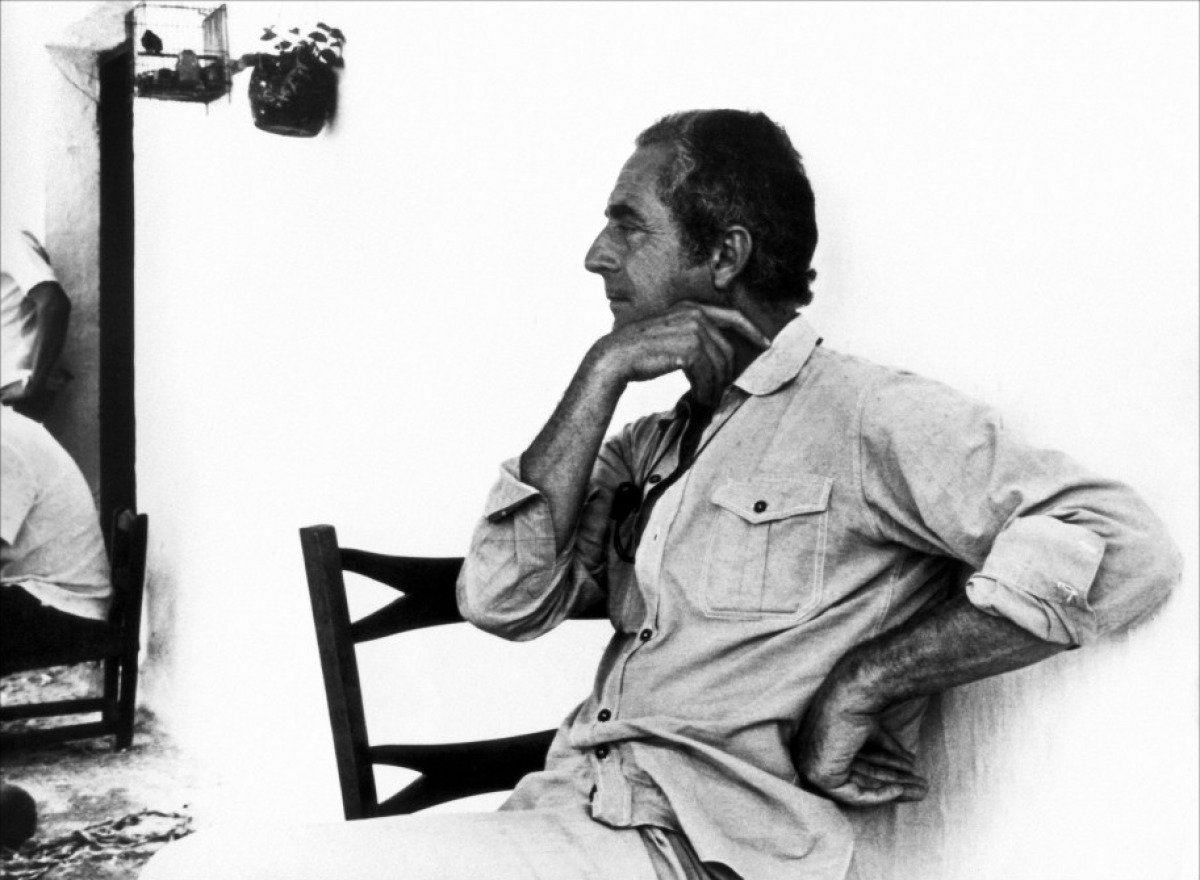

In the hope of learning the answers to these and many other questions about him, his art and his anomie, we decided to approach the elusive Il Dottore with our request for an exclusive interview. His reluctance to see the press and his monosyllabic evasiveness when cornered, are legend; but after more than a month of pursuit by telephone, cable and mail, he finally consented to talk to interviewer Curtis Pepper in Rome—but only subject to the most stringent stipulations He insisted on approving not only the manuscript but the pictures as well: “I have no desire to have monstrous photographs of me floating around” he wired. Of 176 shots we took of him, he rejected all but 25, most of which showed him with his mouth shut, with his hand significantly coveting his mouth or with his face wreathed in a mirthless, inappropriate smile.

Thus began Antonioni’s somber psychoanalysis of 20th Century life, in all its complexity and anonymity. His succeeding films were suffused with a deepening fatalism. Self-destruction was the theme and denouement of both Le Amiche, which Antonioni made in 1955, and Il Grido, completed two years later. Against the background of industrial Turin, Le Amicheilluminated the stilted and superficial lives of a clique of wealthy women who toy with one another’s deepest emotions until one of them finally commits suicide. In Il Grido an itinerant mechanic fathers a child by a married woman; when she rejects him after the death of her husband, he searches, with his daughter, for a new life; frustrated at every turn, he eventually throws himself off a water tower. The film paints an insightful but desolate picture of man in the Machine Age, rendered weak and rootless by the impersonality of his environment.

But the film that marks Antonioni’s coming of age as a director is L’Avventura (1960), the first of a cynical series about love among the affluent. It begins with the disappearance of a wealthy Roman girl whose lover, Sandro, and best friend, Claudia, begin a frenzied search for her. Soon they are lovers, however, and the missing girl is forgotten. But as they wander through the pleasure-filled world of Riviera resorts, Sandro pauses to accept the wares of a prostitute. Discovered by Claudia, he can only protest his frailty; to absolve herself of guilt for her own betrayal—of her lost friend—she resignedly forgives him. Thus fidelity and love itself have succumbed to ennui.

The next film in the series, La Notte, covers a day in the life of a long-married and still affectionate but loveless—couple. Giovanni, a successful novelist, circulates in the world of Milanese culture; Lidia, disillusioned by his ebbing spiritual resources, accompanies him on a visit to a dying friend, to a publication-day cocktail party, then takes a lonely walk through the places where they once lived, searching for time past. That evening, they go—separately—to a marathon party given by a wealthy industrialist, where Giovanni makes a halfhearted attempt to seduce the host’s beautiful daughter. Toward dawn, Lidia scornfully confronts him with a passionate letter he had written to her years before. Ignoring the letter’s implication —that he has since become emotionally, if not sexually, impotent—he makes love to her, but with a chilling new realization of his own psychic isolation. Marriage has kept them united in body but not in spirit, and their only reason for staying together is knowledge of each other’s needs.

If lovers are doomed to infidelity and if marriage must lose its meaning, is there value in any human contact? L’Eclisse, Antonioni’s next film, answered this question with a sobering portrayal of a young woman’s melancholy conclusion, after two unsatisfactory affairs, that men are islands and that true communication is impossible; attempts at constancy in love only hasten its demise. Antonioni ended the picture with a remarkable silent sequence, seven minutes long, in which the camera explores the streets and buildings of a futuristic Roman suburb—a stark symbol of a bleak and sterile hereafter.

Antonioni’s first color film, the subtly shaded Red Desert, concerns the futile search of a woman, whose husband is too preoccupied to care about her, for reassurance in the arms of another man. After this self-diminishing transgression, she wanders aboard a ship and explains to a sailor she happens to encounter, in an extended soliloquy, that she must return to face the responsibilities of her life. Despite the tragic tone of the ending, Antonioni seemed to be saying that acceptance and flexibility are the keys to survival in a shallow, shifting world.

Having dissected—and interred—Italy’s “decadent’’ middle class, Antonioni was restless for a change of scene. A visit with Monica Vitti in England two years ago exposed him to “swinging London” where youth was radically recasting Britain’s stuffy pipe-and-slippers image. The result was Blow-Up, a film that dazzled and shocked both critics and audiences around the world. The protagonist is a successful young fashion photographer who occasionally sallies from the pop op fantasy world of his studio to go slumming for socially pertinent candid shots in the “real” world. While enlarging prints of a couple in a public park, he suddenly discovers that he has recorded what seems to be evidence of a murder. But when he seeks counsel from his pot-smoking friends, he finds that to them the murder of a stranger is totally insignificant. Dejectedly wandering through the park—after discovering that the body has been spirited away—the photographer meets a group of students, their faces painted white, who are playing tennis with an imaginary ball. He joins their game. Moral: Reality is what one chooses to believe is real.

In projecting this personal reality on the screen, Antonioni has discarded the standard film clichés, striving instead for the sleek, uncluttered look, the unfettered flow of action, the almost ascetically understated dialog and emotions that are essential to his cerebral cinematic style. While this unique “grammar” of the cinema, like his dark thematic preoccupations, has always been controversial, critical debate has never been more animated—or divided—than over the “meaning’’ of Blow-Up, why he chose to shoot it in English and in London and why its mood of passionless abandon is in such sharp contrast to his earlier, more somber works.

In the hope of learning the answers to these and many other questions about him, his art and his anomie, we decided to approach the elusive Il Dottore with our request for an exclusive interview. His reluctance to see the press and his monosyllabic evasiveness when cornered, are legend; but after more than a month of pursuit by telephone, cable and mail, he finally consented to talk to interviewer Curtis Pepper in Rome—but only subject to the most stringent stipulations He insisted on approving not only the manuscript but the pictures as well: “I have no desire to have monstrous photographs of me floating around” he wired. Of 176 shots we took of him, he rejected all but 25, most of which showed him with his mouth shut, with his hand significantly coveting his mouth or with his face wreathed in a mirthless, inappropriate smile.

Our conversations with him took place in his modest, book strewn apartment on the periphery of Rome, across the river from the elegant Parioli district that has spawned prototypes for many of his world-weary characters. On the floor above, not coincidentally, lives Monica Vitti, the coolly seductive blonde actress who has long been the maestro’s leading lady in private life as well as on the screen. Antonioni answered our questions with veiled restraint, inadvertently punctuating his remarks with the facial tic he has been afflicted with since youth. The first version of the interview, which we sent to him for corrections, was a spare, impressionistic yet compelling portrait of this enigmatic man: although it was far from a revealing document, he fell he had confessed “loo much” and wired that he was unhappy with the interview and needed time to correct it. The “corrected” copy was cut to three quarters of its original length, and what remained was severely modified. In subtly shaded tones of gray, Antonioni had succeeded in communicating how non-communicative he really is—but this veil of mystery is both Antonioni’s public image and his chosen reality, in his life and in his films. In his assiduous effort to remain hidden behind it, we feel that he may have drawn if aside; but one can’t be sure, for the man glimpsed behind it—like the “inner meaning” divined by critics in his multileveled films—may simply be another mask. The reader, like the viewer, must decide for himself.

Playboy: Your last film, Blow-Up, was shot in London. Were you trying to avoid censorship troubles in Italy because of its erotic scenes?

Antonioni: The eroticism has nothing to do with Blow-Up. There are some scenes where you see nudes, but these are not what’s important in the film. Italian censors have passed it with very little cutting.

Playboy: Was it intentional, in the scene where the photographer has an orgy with the two girls in his studio, that pubic hairs appear visible?

Antonioni: I didn’t notice. If you can tell me where, I’ll go and look.

Playboy: Do you feel that moviemakers should be free to depict total nudity on the screen?

Antonioni: I don’t think it’s necessary. The most important scenes between a man and a woman don’t happen when they are naked.

Playboy: Is there anything you think shouldn’t be shown on the screen?

Antonioni: There can be no censorship better than one’s own conscience.

Playboy: What made you choose London as the setting for Blow-Up?

Antonioni: I happened to be there by chance, to see Monica Vitti while she was working in Modesty Blaise. I liked the happy, irreverent atmosphere of the city. People seemed less bound by prejudice.

Playboy: In what sense?

Antonioni: They seemed much freer; I felt at home. In some way, I was impressed. Perhaps something changed inside me.

Playboy: How?

Antonioni: I’m no good at understanding myself. But those things I knew before that interested me now seem too limited. I feel I need other experiences, to see other people, learn new things.

Playboy: Was it difficult working in a foreign country?

Antonioni: Blow-Up had a rather special story, about a photographer, and I followed the work of some of the more important ones, which made it easier. Also, he moved through a limited environment in London—a minority but elite group of swingers.

Playboy: Apart from its setting, how does Blow-Up differ from your previous films?

Antonioni: Radically. In my other films, I have tried to probe the relationship between one person and another—most often, their love relationship, the fragility of their feelings, and so on. But in this film, none of these themes matters. Here, the relationship is between an individual and reality—those things that are around him. There are no love stories in this film, even though we see relations between men and women. The experience of the protagonist is not a sentimental nor an amorous one but, rather, one regarding his relationship with the world, with the things he finds in front of him. He is a photographer. One day, he photographs two people in a park, an element of reality that appears real. And it is. But reality has a quality of freedom about it that is hard to explain. This film, perhaps, is like Zen; the moment you explain it, you betray it. I mean, a film you can explain in words is not a real film.

Playboy: Would you call Blow-Up, like so many of your others, a pessimistic film?

Antonioni: Not at all, because at the end, the photographer has understood a lot of things, including how to play with an imaginary ball—which is quite an achievement.

Playboy: Then you feel that the photographer’s decision to join the game and forget about the murder is a positive solution. Do you think this speaks well of the way youth deals with its problems?

Antonioni: Certainly. There’s much talk about the problems of youth, but young people are not a problem. It’s a natural evolution of things. We, who have known only how to make war and slaughter people, have no right to judge them, nor can we teach them anything.

Playboy: Some people over 30 seem to feel that today’s youth is a lost generation, withdrawn not only from commitment but, in the case of the hippies, from reality. Do you disagree?

Antonioni: I don’t think they’re lost at all. I’m not a sociologist nor a psychologist, but it seems to me they are seeking a new way to be happy. They are committed, but in a different way—and the right way, I think. The American hippies, for example, are against the war in Vietnam and against Johnson—but they combat the warmongers with love and peace. They demonstrate against police by embracing them and throwing flowers. How can you club a girl who comes to give you a kiss? That, too, is a form of protest. In California’s “loving parties,” there is an atmosphere of absolute calm, tranquillity. That, too, is a form of protest, a way of being committed. It shows that violence is not the only means of persuasion. It’s a complicated subject—more so than it seems—and I can’t handle it, because I don’t know the hippies well enough.

Playboy: Sometimes that tranquillity you spoke of is induced by hallucinogenic drugs. Does the use of such drugs alarm you?

Antonioni: No; some people have negative reactions or can’t stand hallucinations, but others stand them extremely well. One of the problems of the future world will be the use of leisure time. How will it be filled up? Maybe drugs will be distributed free of charge by the government.

Playboy: You’ve always emphasized both the importance and the difficulty of communication between people in your films. But doesn’t the psychedelic experience tend to make people withdraw into an inner-directed mysticism, even drop out of society altogether? And doesn’t this tend to destroy communication?

Antonioni: There are many ways of communicating. Some hold the theory that new forms of communication between people can be obtained through hallucinogenic drugs.

Playboy: Would you want to try some yourself?

Antonioni: You can’t go to an LSD or pot party unless you take it yourself. If I want to go, I must take drugs myself.

Playboy: Have you?

Antonioni: That’s my business. But to show you the new mentality: I visited St. Mark’s in Venice with a young woman who smokes pot, as do most young people in her environment. When we were above the gilded mosaics—St. Mark’s is small and intimate—she exclaimed, “How I’d like to smoke here!” You see how new that reaction is? We don’t even suspect it. There was nothing profane in her desire to smoke; she merely wanted to make her aesthetic emotions more intense. She wanted to make her pleasure giant-size before the beauty of St. Mark’s.

Playboy: Does this mean you believe that the old means of communicating have become masks, as you seem to suggest in your films, that obscure communication?

Antonioni: I think they become masks, yes.

Playboy: Is alienation, then—from one’s self and from others—the subject of your films?

Antonioni: I never think in terms of alienation; it’s the others who do. Alienation means one thing to Hegel, another to Marx and yet another to Freud; so it is not possible to give a single definition, one that will exhaust the subject. It is a question bordering on philosophy, and I’m not a philosopher nor a sociologist. My business is to tell stories, to narrate with images—nothing else. If I do make films about alienation—to use that word that is so ambiguous—they are about characters, not about me.

Playboy: But your characters do have difficulty communicating. The industrial landscape in Red Desert, for example, seems to leave little room for human emotion. It seems to dehumanize the characters.

Antonioni: Nothing regarding man is ever inhuman. That’s why I make films, not iceboxes. I shot some of Red Desert along a road where half the horizon was filled with the pine trees that still surround Ravenna—though they are vanishing fast—while the other half of the skyline was taken up with a long line of factories, chimneys, tanks, grain silos, buildings, machinery. I felt that the skyline filled with things made by man, with those colors, was more beautiful and richer and more exciting for me than the long, green, uniform line of pinewoods, behind which I still sensed empty nature.

Playboy: Most of the men in your films seem to cope very easily with this new technological reality, as far as their work relationships are concerned. But in their love relationships, they tend to be incapable of achieving or sustaining an emotional involvement. Compared with your female characters, they seem weak, lacking in initiative.

Antonioni: What do you mean—that there exists an ideal relationship between man and woman? Do you really think a man must be strong, masculine, dominating, and the woman frail, obedient and sensitive? This is a conventional idea. Reality is quite different.

Playboy: Is that what you meant when you said once that women are the first to adapt themselves to an epoch, that they are closer to nature and thus stronger?

Antonioni: I said women were a finer filter of reality. They can sniff things.

Playboy: You also said that you understand them better than men. Why?

Antonioni: It’s only natural. I’ve had intimate relations with women but not with men.

Playboy: Are the Italian women you’ve known different from those of other nationalities?

Antonioni: Yes, of course.

Playboy: How?

Antonioni: This is becoming frivolous. It leads to such platitudes as that French women are calculating; Italian women, instinctive; English women, hot. The women I like, no matter what nationality, all seem to have more or less the same qualities. Perhaps this is because one goes looking for them—that is, you like that type of woman and then look for her. I’ve always dreamed of getting to know the women of other countries better. When I was a boy, I remember, I used to get angry at the thought that I did not know German or American or Swedish women. I hope the women in my films have at least a minimal common denominator with the women of other countries, because, after all, the problems are more or less the same.

Playboy: Your heroines tend to be mature in years. Do you find older women more attractive than young girls?

Antonioni: It depends upon the age of the woman you’re in love with.

Playboy: What do you find most attractive sexually in a woman?

Antonioni: A woman’s sex appeal is an inner matter. It stems from her mental make-up, basically. It’s an attitude, not just a question of her physical features—that arrogant quality in a woman’s femininity. Otherwise, all beautiful women would have sex appeal, which is not so.

Playboy: Do you think there can be love without eroticism between a man and a woman?

Antonioni: I believe it’s all the same thing. I can’t imagine love without a sexual charge.

Playboy: In your films, though, you imply that love is more complex, that even when two people are attracted to each other, they have to struggle to keep their love alive. Why?

Antonioni: That love is a conflict seems to me obvious and natural. There isn’t a single worthwhile work in world literature based on love that is only about the conquest of happiness, the effort to arrive at what we call love. It’s the struggle that has always interested those who produce works of art—literature, cinema or poetry. But I can’t give any absolute definition of what love is, or even whether it ought to exist.

Playboy: Love seems to bring little happiness to your characters. Has this been true of your own life?

Antonioni: I read somewhere that happiness is like the bluebird of Maeterlinck: Try to catch it and it loses its color. It’s like trying to hold water in your hands. The more you squeeze it, the more the water runs away. Personally, I know very little about love.

Playboy: How do you feel about marriage?

Antonioni: I’m more or less skeptical about marriage, because of family ties, relations between children and parents—it’s all so depressing. The family today counts for less and less. Why? Who knows—the growth of science, the Cold War, the atomic bomb, the world war we’ve made, the new philosophies we’ve created; certainly something is happening to man, so why go against it, why oblige this new man to live by the mechanisms and regulations of the past?

Playboy: What about religion? Do you agree with those who say God is dead?

Antonioni: I remember a character in a Hemingway story who was asked, “Do you believe in God?” And he answered, “Sometimes, at night.” When I see nature, when I look into the sky, the dawn, the sun, the colors of insects, snow crystals, the night stars, I don’t feel a need for God. Perhaps when I can no longer look and wonder, when I believe in nothing—then, perhaps, I might need something else. But I don’t know what. All I know is that we are loaded down with old and stale stuff—habits, customs, old attitudes already dead and gone. The strength of the young Englishmen in Blow-Up lies in their ability to throw out all such rubbish.

Playboy: What besides marriage and religion would you throw out?

Antonioni: The sense of nation, “good breeding,” certain forms and ceremonies that govern relationships—perhaps even jealousy. We’re not aware of all of them yet, though we suffer from them. And they mislead us not only about ethics but also about aesthetics. The public buys “art”—but the word is drained of its meaning. Today we no longer know what to call art, what its function is and even less what function it will have in the future. We know only that it is something dynamic—unlike many ideas that have governed us.

Playboy: What sort of ideas?

Antonioni: Take Einstein; wasn’t he looking for something stable and changeless in this enormous, constantly changing melting pot that is the universe? He sought fixed rules. Today, instead, it would be helpful to find all those rules that show how and why the universe is not fixed—how this dynamism develops and acts. Then maybe we will be able to explain many things, perhaps even art, because the old instruments of judgment, the old aesthetics, are no longer of any use to us—so much so that we no longer know what’s beautiful and what isn’t.

Playboy: Many critics have called you one of the foremost directors in the search for a new aesthetic, in changing the “grammar” of the cinema. Do you feel you’ve brought any innovations to the screen?

Antonioni: Innovation comes spontaneously. I don’t know if I’ve done anything new. If I have, it’s just because I had begun to feel for some time that I couldn’t stand certain films, certain modes, certain ways of telling a story, certain tricks of plot development, all of it predictable and useless.

Playboy: Was it the old techniques that bothered you—or simply the old story lines?

Antonioni: Both, I think. The basic divergence was in substance, in what was being filmed—and this had been determined by the insecurity of our lives. A particular type of film emerged from World War Two, with the Italian neorealist school. It was perfectly right for its time, which was as exceptional as the reality around us. Our major interest focused on that and on how we could relate to it. Later, when the situation normalized and post-war life returned to what it had been in peacetime, it became important to see the intimate, interior consequences of all that had happened.

Playboy: Doesn’t your own interest in the interior of external events, in man’s reaction to reality, date back to before the war? Your first film venture, a documentary, was shot in a mental hospital in Ferrara. Why did you choose that subject?

Antonioni: As I suffer from nervous tics, I had gone for consultation to a neurologist who was in charge of this mental home. Sometimes I had to wait, and found myself in contact with the insane, and I liked the atmosphere. I found it full of poetic potential. But the film was a disaster.

Playboy: Why?

Antonioni: I wanted to do it with real schizophrenics, and the director of this hospital agreed. He was a bit mad himself—a very tall man who demonstrated reactions of mad people to pain by rolling about on the floor with the rest of them. But he provided me with some schizophrenics and I chatted with them, explaining how they were supposed to move in the first scene. They were amazingly docile and they did everything in rehearsal as I asked them. Everything was fine—until we lit the klieg lights and they came under a glare that they’d never seen before. All hell broke loose. They threw themselves on the ground; they began to howl—it was ghastly. We were in a sea of them and I was absolutely petrified. I hadn’t even the strength to shout “Stop!” So we didn’t shoot the documentary; but I’ve never forgotten that scene.

Playboy: You left Ferrara to attend the University of Bologna. What made you decide not to return to Ferrara? Didn’t you like it there?

Antonioni: I enjoyed myself tremendously in Ferrara. The troubles began later. But I didn’t like university life much at Bologna. The subjects I studied—economics and business administration—didn’t interest me. I wanted to make films. I was glad when I was graduated. Yet it’s odd; on graduation day, I was overcome with a terrible sadness. I realized that my youth was over and now the struggle had begun.

Playboy: And you went to Rome?

Antonioni: Yes; and the early years there were very hard. I wrote reviews for a film magazine; and when they fired me, I was penniless for days. I even stole a steak from a restaurant. Someone had ordered it but was away from the table when it came, so I put it in a newspaper and ran out. My father had money—he was then a small industrialist—and he wanted me back in Ferrara. But I refused and lived by selling tennis trophies; I had boxes full of them that I’d won in tournaments during college days. I pawned and sold them all. I was miserable, since I’d won them myself.

Playboy: How did you switch from film criticism to film directing?

Antonioni: I went to the Experimental Film Center in Rome, but stayed only three months. The technical aspect of films—by itself alone—has never interested me very much. After you’ve learned two or three basic rules of cinema grammar, you can do what you like—including breaking those rules.

Playboy: Then you began to direct?

Antonioni: No, it wasn’t that easy. At first I wrote film scripts. I did one with Rossellini, called Un Pilota Ritorna. I’ll never forget Roberto. In those days, he lived in a big empty house he’d found in Rome and was almost always in bed, because it was the only piece of furniture he had. We worked on his bed, with him in it. From this I moved on to other things, until I was drafted into the army. The hell began then.

Playboy: Because of army life?

Antonioni: No, the nightmare was to work on the set of a film I had helped write—I Due Foscari, with Enrico Fulchignoni directing—and still show up as a soldier. I used to sneak out of camp at night and crawl back at dawn, over a wall or sometimes through a hole under a hedge. It was freezing and I was paralyzed from this and from sheer exhaustion.

Playboy: Why did you keep going back over the wall?

Antonioni: Because of the excitement of working on a film, although only in a small way as an assistant. They let me experiment and I learned a lot, especially about camera movement and how to relate the movement of actors to the field of your lens.

Playboy: Did you work on any other films while you were in the army?

Antonioni: Michele Scalera [head of Scalera Films] called me in one day and asked me if I’d like to go to France to work with Marcel Carné—as his co-director—on a picture being co-produced by Scalera. I couldn’t believe it—co-direct with this man who was the greatest of his day—and said yes. I had to pull strings all over Rome to get leave from the army. Then, when I got it, I was stopped at the French border. It was maddening. When I finally got to Paris, it was Sunday and I found Carné shooting in the suburbs. He looked at me like I had brought the plague. Finally, he said, “You’ve got eyes, my friend. Look.” After that, he said nothing more to me. I didn’t dare tell him I was supposed to be the co-director. I merely said I was to be his assistant; but I was never even that. We went to Nice for some exteriors and the train was so crowded I rode on the car steps, hanging on for my life. Carné spoke to me again, then—obviously scared I’d get hurt and he’d have to pay for it. At Nice we stayed at the Negresco, where I began to enjoy myself a bit. I met the nursemaid of a rich family and made some notes for a film on the life of a great hotel, seen from the back rooms. Somewhere along the line, I eventually lost the notes, but I’ll never forget Carné. Scalera had wanted me to stay on in France and work with Gremillion and Cocteau, but my leave ran out and I had to hurry back to the army in Italy.

Playboy: Mussolini’s regime collapsed shortly afterward. How did this affect you?

Antonioni: It forced me into a hand-to-mouth existence. During the German Occupation of Rome, cinema didn’t exist. I earned a little money by doing translations—Gide’s La Porte Etroite, Morand’s Monsieur Zero. But then I became involved with the Action party and the Germans looked for me. I escaped to the Abruzzi hills, but they followed me there and I had to escape once more. Finally, when the Allies took Rome, we could begin again.

Playboy: Did that lean period color the political or social outlook of your later films?

Antonioni: That had already begun, long before. When I was a boy, we often went with friends to swim in the Po, which flows near Ferrara. There were barconi, great river boats towed by men dragging them from the towpath. Men pulling five or six boats, against a river’s current, made a tremendous impression on me. I returned time and again to stare at them and at the people who lived on them, with their families and chickens, and washing hung out; the boat was their home. It was here that I got my first glimpse of the bad distribution of wealth. Later, I began to make Gente del Po [People of the Po]. It was my first documentary and the first time I ever handled a cinecamera.

Playboy: Yet your first feature—Cronaca di un Amore, in 1950—caused a sensation by breaking with the neorealistic school’s penchant for portraying the working class. This film and most of those you’ve made since then are about the affluent middle class. Why?

Antonioni: I’ve made films about the middle classes because I know them best. Everyone talks about what he knows best. The struggle for life is not only the material and economic one. Comfort is no protection from anxiety. In any case, the idea of giving “all” of reality is overly simple and absurd. I take a subject and analyze it, as in a laboratory. The deeper I can go in the analysis, the smaller the subject becomes—and the better I know it. This doesn’t prevent a return from the particular subject to the general, from the isolated character to the entire society. But in Cronaca di un Amore, I was interested in seeing what the war had done more to the mind and spirit of individuals than to their place in the framework of society. That’s why I began to make films that the French critics described as “interior neorealism.” The aim was to put the camera inside the characters—not outside. The Bicycle Thief was a great film in which the camera remained always outside the characters. Neorealism also taught us to follow the characters with the camera, allowing each shot its own real interior time. Well, I became tired of all this; I could no longer stand real time. In order to function, a shot must show only what is useful.

Playboy: Why couldn’t you stand real time?

Antonioni: Because there are too many useless moments. It’s pointless to describe them.

Playboy: Your insistence on paring the superfluous from your films is also reflected in the sparseness of your dialog. Is that why you prefer to establish the dark, cold mood of your films with a background of gray, cloudy skies?

Antonioni: In the early days, the films I shot in black and white were fairly dramatic, so the gray sky helped create an atmosphere. Cronaca di un Amore, for example, was set in Milan in winter—which was correct for climate and mood. But the sun also limits movements. At that time, I used very long shots, turning through 180 degrees; it’s obvious that the sun will stop you from doing that sort of thing. So, with a gray sky you move ahead faster, without problems of camera position.

Playboy: In your last two films, you’ve switched to color. You’ve kept the gray skies, but you’ve been known to change the colors of roads and buildings for effect. What don’t you like about real colors?

Antonioni: Wouldn’t it be ridiculous if you asked a painter that same question? It’s untrue to say the colors I use are not those of reality. They are real: The red I use is red; the green, green; blue, blue; and yellow, yellow. It’s a matter of arranging them differently from the way I find them, but they are always real colors. So it’s not true that when I tint a road or a wall, they become unreal. They stay real, though colored differently for my scene. I’m forced to modify or eliminate colors as I find them in order to make an acceptable composition. Let’s suppose we have a blue sky. Who knows if it’s going to work; or, if I don’t need it, where can I put it? So I pick a gray day for a neutral background, where I can insert all the color elements I need—a tree, a house, a ship, a car, a telegraph pole. It’s like having a white paper on which to apply colors. If I begin with a blue sky, half the picture is already painted blue. But what if I don’t happen to need blue? Color forces you to invent. It’s more than just a challenge, though. There are practical reasons for working in it today. Reality itself is steadily becoming more colored. Think of what factories were like, especially in Italy at the beginning of the 19th century, when industrialization was just beginning: gray, brown and smoky. Color didn’t exist. Today, instead, most everything is colored. The pipe running from the basement to the 12th floor is green because it carries steam. The one carrying electricity is red, and that with water is purple. Also, plastic colors have filled our homes, even revolutionized our taste. Pop art grew out of that and was possible because of this change in taste. Another reason for switching to color is world television. In a few years, it will all be in color, and you can’t compete against that with black-and-white films.

Playboy: Besides the switch to color, have your methods of filming a picture changed much from the early days?

Antonioni: I’ve never had a method of working. I change according to circumstances; I don’t employ any particular technique or style. I make films instinctively, more with my belly than with my brain.

Playboy: How does the process begin?

Antonioni: With a theme, a small idea that develops within me. The idea for the next film, which I want to make in America, came to me from something I can’t tell you about fully, because it would mean telling the story of the film. But someone told me of an absurd little episode, saying, “Just think what happened to me today. I couldn’t come for this and that reason.” I went home and thought about it—and upon that small episode I began to build, until I found I had a story, growing out of a small event. You put in everything that accumulates inside you. And it’s an enormous quantity of stuff—mostly from watching and observing. The way I relax, what I like doing most, is watching. That’s why I like traveling, to have new things before my eyes—even a new face. I enjoy myself like that and can stay for hours, looking at things, people, scenery. Do you know, when I was a boy, I always had bumps on my head from running into mailboxes because I was always turning around to stare at people. I also used to climb onto window sills to look into houses—yes, I was crazy—to peek at someone I’d seen in the window. So around the kernel of an idea or an episode, you instinctively add all you have accumulated by watching, talking, living, observing.

Playboy: And then you begin to write a script?

Antonioni: No, that’s the last thing I do. When I’m sure I have a story, I call my collaborators and we begin to discuss it. And we conduct studies of certain subjects to make sure of our terrain. Then, finally, in the last month or two, I write the story.

Playboy: How long does this gestation period last?

Antonioni: Perhaps six months. Then I start shooting.

Playboy: When do you pick your actors?

Antonioni: When you work on a character, you form in your mind an image of what he ought to look like. Then you go and find one who resembles him. For Blow-Up, I began with photographs sent by agents, throwing them out one by one. Then I went around looking into theaters. I found David Hemmings in a small London production.

Playboy: Once you’ve cast the film and begin to shoot, do you stick to your script or ignore it?

Antonioni: The script is a starting point, not a fixed highway. I must look through the camera to see if what I’ve written on the page is right or not. In the script, you describe imagined scenes, but it’s all suspended in mid-air. Often, an actor viewed against a wall or a landscape, or seen through a window, is much more eloquent than the lines you’ve given him. So then you take out the lines. This happens often to me and I end up saying what I want with a movement or a gesture.

Playboy: At what point does this take place?

Antonioni: When I have the actor there, beginning to move, I notice what is useful and what is superfluous and eliminate the superfluous—but only then, at that moment. That’s why they call it improvisation, but it’s not; it’s just making the film. Everything you do before consists of notes; the script is simply a series of notes for the film.

Playboy: How closely do your scripts conform to the final product?

Antonioni: I rewrite the scenarios afterward, when I’ve already made the film and I know what I wanted to do.

Playboy: It’s said that you insist on being left alone on the set for 15 or 20 minutes before beginning to shoot. True?

Antonioni: Yes. Before each new setup, I chase everyone off the set in order to be alone and look through the camera. In that moment, the film seems quite easy. But then the others come in and everything becomes difficult.

Playboy: If you go on changing scenes right through to the last stroke of the clapstick, it must be rough on the actors, too. Do you think that’s why some of them say it’s difficult to work for you?

Antonioni: Who says so? I really don’t believe that’s true. I simply know what the actor’s attitude should be and what he should say. He doesn’t, because he can’t see the relationship that begins to exist between his body and the other things in the scene.

Playboy: But shouldn’t he understand what you have in mind?

Antonioni: He simply must be. If he tries to understand too much, he will act in an intellectual and unnatural manner.

Playboy: Do you prefer, then, not to talk to the actor about his role?

Antonioni: No, it’s obvious that I must explain what I want from him, but I don’t want to discuss everything I ask him to do, because often my requests are completely instinctive and there are things I can’t explain. It’s like painting: You don’t know why you use pink instead of blue. You simply feel that’s how it should be—pink. Then the phone rings and you answer it. When you come back, you don’t want pink anymore and you use blue—without knowing why. You can’t help it; that’s just the way it is.

Playboy: So you want your actors to do what you tell them without asking questions and without trying to understand why?

Antonioni: Yes. I want an actor to try to give me what I ask in the best and most exact way possible. He mustn’t try to find out more, because then there’s the danger that he’ll become his own director. It’s only human and natural that he should see the film in terms of his own part, but I have to see the film as a whole. He must therefore collaborate selflessly, totally. I’ve worked marvelously with Monica [Vitti] and Vanessa [Redgrave] because they always tried to follow me. It’s never important for me if they don’t understand, but it is important that I should have recognized what I wanted in what they gave me—or in what they proposed.

Playboy: Is it true that you sometimes deliberately misdirect actors, giving them a false motivation to produce the reaction you really want from them?

Antonioni: Of course, I tell them something different, to arrive at certain results. Or I run the camera without telling them. And sometimes their mistakes give me ideas I can use, because mistakes are always sincere, absolutely sincere.

Playboy: Have you ever worked with Method actors?

Antonioni: They’re absolutely terrible. They want to direct themselves, and it’s a disaster. Their idea is to reach a certain emotional charge; actors are always a little high at work. Acting is their drug. So when you put the brakes on, they’re naturally a little disappointed. And I’ve always played down the drama in my films. In my main scenes, there’s never an opportunity for an actor to let go of everything he’s got inside. I always try to tone down the acting, because my stories demand it, to the point where I might change a script so that an actor has no opportunity to come out well. I say this for Monica, too. I’m sure that she has never given all she could in my films, because the scenes just weren’t there. Take a film like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? It offers an actress every possibility. If she’s really good and has qualities like Liz Taylor, it comes out. But Liz Taylor never displayed these qualities in other films, because she never had a part like that.

Playboy: Some directors claim it’s difficult to direct a woman they love. Is this true with Monica Vitti?

Antonioni: I have no difficulty, because I forget about the relationship between myself and any actress when working with her.

Playboy: Would you number Monica among the most gifted actresses you’ve ever seen?

Antonioni: Monica is certainly the first who comes to my mind. I can’t think of another as good as Vanessa, as strong as Liz Taylor, as true as Sophia Loren or as modern as Monica. Monica is astonishingly mobile. Few actresses have such mobile features. She has her own personal and original way of acting.

Playboy: What about directors? Have you any favorites?

Antonioni: They change, like favorite authors. I had a passion for Gide and Stein and Faulkner. But now they’re no use to me anymore. I’ve assimilated them—so, enough, they are a closed chapter. This also applies to film directors. Also, when I see a good film, it’s like a whiplash. I run away, in order not to be influenced. Thus, the films I liked most are those I think least about.

Playboy: Are you an admirer of Ingmar Bergman?

Antonioni: Yes; he’s a long way from me, but I admire him. He, too, concentrates a great deal on individuals; and although the individual is what interests him most, we are very far apart. His individuals are very different from mine; his problems are different from mine—but he’s a great director. So is Fellini, for that matter.

Playboy: What do you do between films? Do you feel the same emptiness as Fellini when you’re not working?

Antonioni: I don’t know how it is with Fellini. I never feel empty. I travel a lot and I think about other films.

Playboy: Are you ever bored?

Antonioni: I don’t know. I never look at myself.

Playboy: Have you ever known anyone who has understood you?

Antonioni: Everyone has understood me in his own way. But I would have to understand myself first in order to judge—and so far, I haven’t.

Playboy: Have you many friends?

Antonioni: The close friends remain fairly fixed. The older I get, the more I like people whom we call mezzi matti—half crazy. I like them best because they fit into my conviction that life should be taken ironically; otherwise, it becomes a tragedy. Fitzgerald said a very interesting thing in his diary; that human life proceeds from the good to the less good—that is, it’s always worse as you go on. That’s true.

Playboy: You’ve said your films always leave you unsatisfied. Isn’t that true of the work of most creative artists?

Antonioni: Yes, but especially for me, since I’ve always worked under fairly disastrous conditions economically.

Playboy: Have all the lost years—the time wasted fighting against incomprehension from producers—left you bitter?

Antonioni: I try not to think about it. I dislike judging myself, but I will say I would be wealthy today if I had accepted all the films that have been offered to me with large sums of money. But I’ve always refused, in order to do what I felt like doing.

Playboy: Have you ever been tempted?

Antonioni: Yes, often.

Playboy: As far as wealth goes, didn’t the success of Blow-Up make you rich?

Antonioni: I’m not rich and maybe I’ll never be rich. Money is useful—yes—but I don’t worship it.

Playboy: What’s your next film? Do you intend to continue working outside Italy?

Antonioni: Quite frankly, I’d like to, but don’t know if I’ll have the strength. It isn’t easy to understand the lives of people different from your own. I’m thinking about doing a film in the United States, as I mentioned earlier, but I don’t know if it will come off.

Playboy: Have you ever considered making an autobiographical film, like some of Fellini’s?

Antonioni: My films have always had an element of immediate autobiography, in that I shoot any particular scene according to the mood I’m in that day, according to the little daily experiences I’ve had and am having—but I don’t tell what has happened to me. I would like to do something more strictly autobiographical, but perhaps I never will, because it isn’t interesting enough, or I won’t have the courage to do it. No, that’s nonsense, because it isn’t a question of courage. It’s simply that I believe in the autobiographical concept only to the degree that I am able to put onto film all that’s passing through my head at the moment of shooting.

Playboy: Have you ever thought about retiring?

Antonioni: I’ll go on making films until I make one that pleases me from the first to the last frame. Then I’ll quit.

Playboy, November 1967

No comments:

Post a Comment