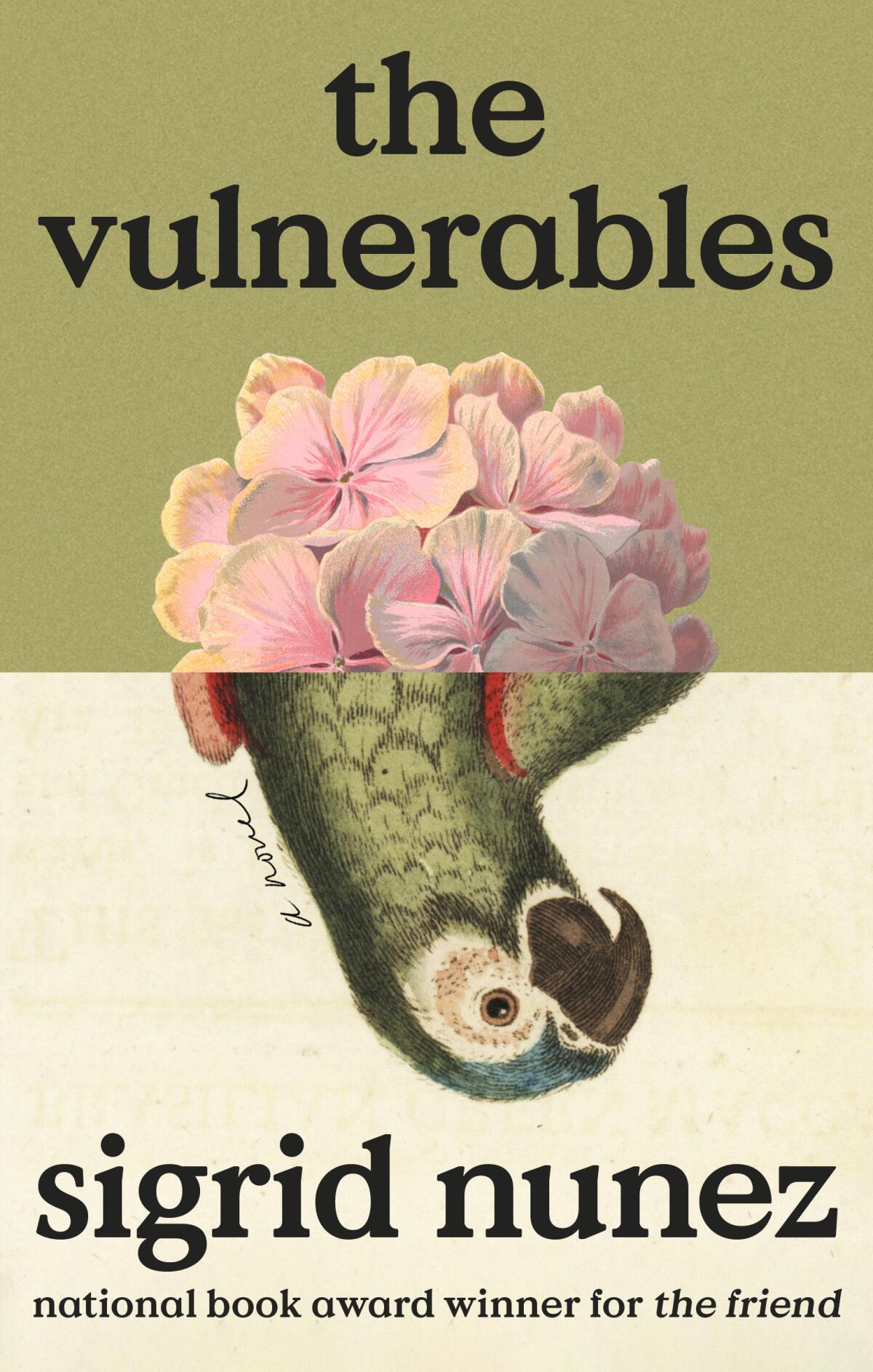

The Vulnerables

By Sigrid Nunez

Riverhead: 256 pages, $

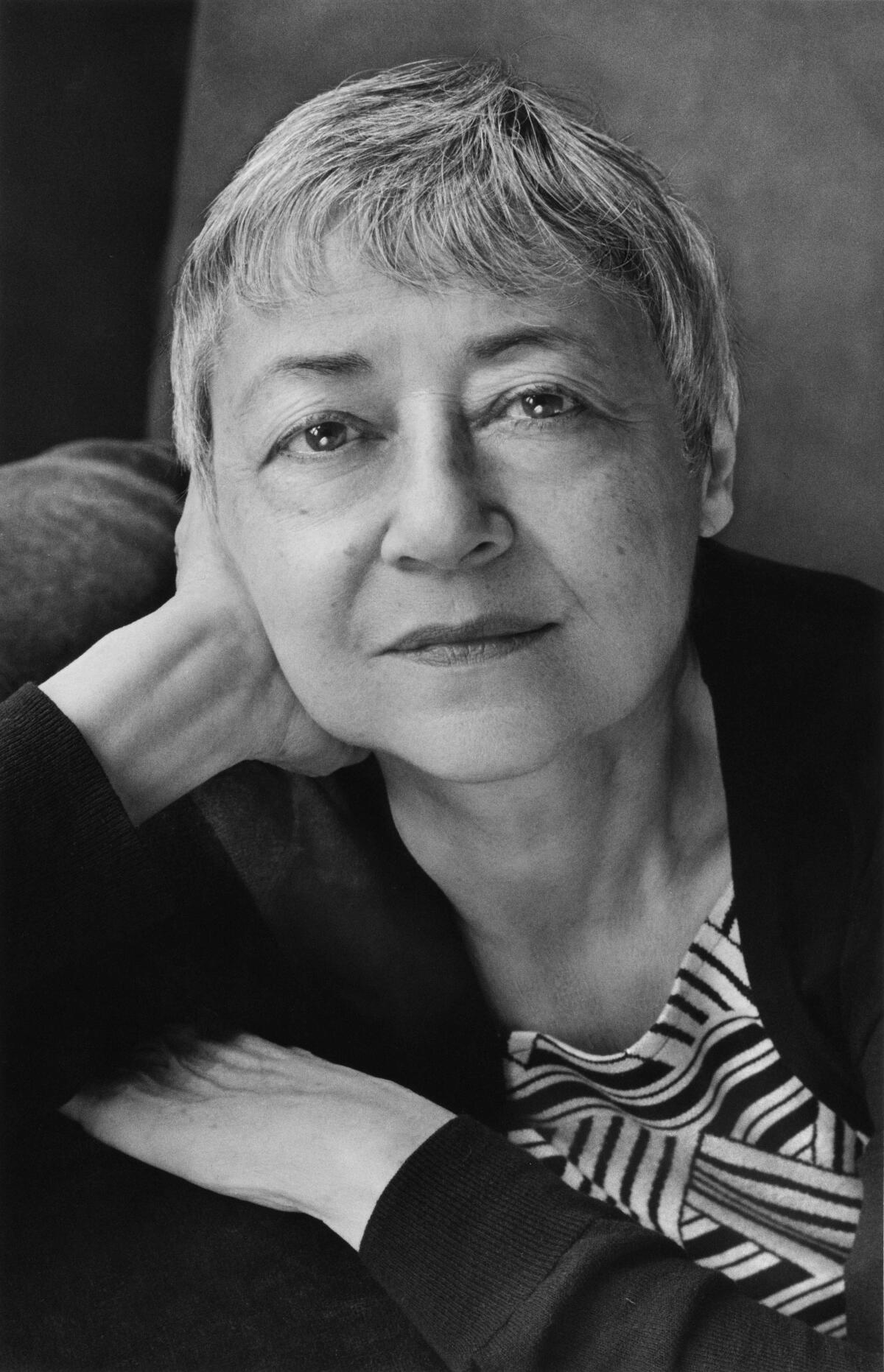

Talking to Sigrid Nunez, much like reading Sigrid Nunez, is deeply pleasurable, immediately intimate. There is warmth but also urgency, and very little artifice. When I ask her a too-vague question about how time feels essential to her fiction, she answers simply, “Well, it just is. I would never be able to explain it.”

We met at the espresso bar of a hotel in Manhattan’s West Village not far from Nunez’s apartment. Both of us were early, and she had just quit the university-teaching grind, so we traded teaching travel stories. Nunez grew up in Brooklyn and on Staten Island, went to Barnard and then Columbia for her MFA, has taught at Princeton, Syracuse, Smith College and Boston University as well as Columbia, The New School, Hunter College and New York University — all without a driver’s license. But now, at 72, in the wake of a 2018 National Book Award for her novel “The Friend,” she is able to step back and settle into the writing life she’s always envisioned.

“The Vulnerables,” out this month, is Nunez’s ninth novel and the third in what she now sees as a trilogy. She didn’t set out to write them as a unit, but as she moved from “The Friend” to 2020’s “What Are You Going Through,” she recognized each had the same voice, same unnamed narrator, same relationship to moving in and out of story, into thought and anecdote.

Each piece of the trilogy also involves an intimate, often very funny relationship to an animal. “As soon as you bring an animal in,” she says, “you’re giving yourself an opportunity to create some warmth and humor.”

Humor is a constant in these books. “Comedy is so much a part of life that I feel like when I read a novel and there’s no humor in it, I feel like something essential is being left out,” she says. This immediately summons for me an image from “The Friend” in which the protagonist uses a child’s pail and shovel to clean up after the Great Dane she has been tasked to care for.

In “The Vulnerables,” the animal, Eureka, is a parrot. Years ago, Nunez lived near a store on Bleecker Street filled with exotic birds. “It was an ear-bleeding sound,” she recalls. “I would try to bring people there and they’d say, ‘I can’t deal. I’ll wait for you outside.’ But you could walk around, and you could hold your hand out and they would come … there were macaws and cockatoos, they were just wonderful.”

The book didn’t start, however, with the parrot. It began, like the others, with the unnamed writer and teacher, now facing the COVID pandemic at over 65 (and hence “a vulnerable”). Every book was built, she says, by “pure instinct. I create everything linearly; when I write, whatever happens comes out of what was written before.” She pulls freely at life, filling her work with readings and ideas that she also has, but the spark is always invention.

“My early reading, what made me passionate about literature was fairy tales, which means magic stuff, which means trees talking and people turning into birds and so on,” she says. “This is what was exciting. And then when I was a little older, I loved Dickens.”

In the case of “The Vulnerables,” the unnamed narrator is spurred out of the isolation of her small apartment and her daily life by an abandoned bird in the apartment of a friend of a friend. Walks and meditations shift to interaction, worry, caretaking; the jokes come more easily with the bird there.

Like the dog in “The Friend” and the cat in “What Are You Going Through,” the bird surprised Nunez before it surprised us. “I want the reader to be reading it the same way I’m writing it,” she says. “I wanted it to feel unplanned because it was unplanned. I mean, there’s a structure, as you know, but a lot of it is serendipitous.”

These inventions differentiate the books from what might otherwise be considered “autofiction” — a nearly meaningless term after years of overuse, but defined loosely as fiction threaded tightly into the consciousness of a writer, who often shares the author’s name, in which what happens feels plotless on purpose, closer to life (or a writer’s version of it) as it actually transpires.

Eureka’s arrival forces Nunez’s deeply internal narrator outside of herself. Weeks later, another surprise arrival, Eureka’s former caretaker — an impossibly fit and deeply troubled 20-something college dropout — forces her into spaces of uncertainty, discomfort: all deeply useful things for books.

“I see my work as hybrid fiction,” Nunez says. While she moves seamlessly from invention to what she terms, courtesy of Javier Marias, “literary thinking,” the constant is a deliberate and careful attention to language, a compulsion, Nunez says “to search.” Each word might spring the narrator into a new scene or tangent — or serve as a barb to hang her up for a page or paragraph.

And what is she searching for? Once, Nunez tells me, a man asked her at a talk if she had “a message.” She laughed — and laughs again telling me this. Of course there is no message, she says. Only didactic empty fiction (I say) has a message. What Nunez is trying to do instead is find meaning, to understand. What makes her search particularly thrilling is its brashness and its erudition, its equal propensity to reach for Nietzsche, J.M. Coetzee or T.S. Eliot or just to play fetch with a bird.

What this feels like is an eventful, rich, addictive conversation with your smartest, funniest and most well-read friend. Except, Nunez says, the conversation takes on new dimensions and new textures when it’s written down. Something happens to her thinking, she says; it’s deepened by the time she spends searching through a book.

“Elizabeth Hardwick used to say only writers ever really think, as if there was no such thing as a scientist or something,” Nunez says, invoking her one-time teacher with a mix of adoration and seasoned skepticism. “What she meant, and what I have found, is that there are these things that are only going to occur to you while you’re writing. I wouldn’t be going for a walk and have all these thoughts. But when I’m actually writing, things occur to me.”

Near the end of “The Vulnerables,” Nunez’s narrator shifts her attention to the state of books: their worth, who reads them, the futility of hurling language at so many existential threats. Perhaps every generation thinks theirs is the scariest and hardest, but this is the one we’re inside of. It often feels terrifying. Near the end of the book, a doctor uses the word “deranged.”

Novels can feel small by contrast — solipsistic, absurd. Nunez and I talked a long time about the state of contemporary fiction, its lack of humor, how pointless it can often seem to devote one’s life to it. (“But then we can’t stop, can we?” Nunez said.) In person as in her novels, Nunez seldom states something she doesn’t later complicate.

“I do think that there’s no real reason to think of your work having a large effect out there in the world,” she says. “First of all, there’s so much work out there. There’s so many novels, there’s so much writing, and it passes quickly.”

But then, a few minutes later, with as much clarity: “There is this beautiful quote where Czeslaw Milosz says: ‘Before you print a poem, you should reflect on whether this verse could be of use to at least one person in the struggle with himself and the world.’ And that I think is a lot to ask, and also enough to ask.”

Strong is a critic and the author, most recently, of the novel “Flight.”

No comments:

Post a Comment