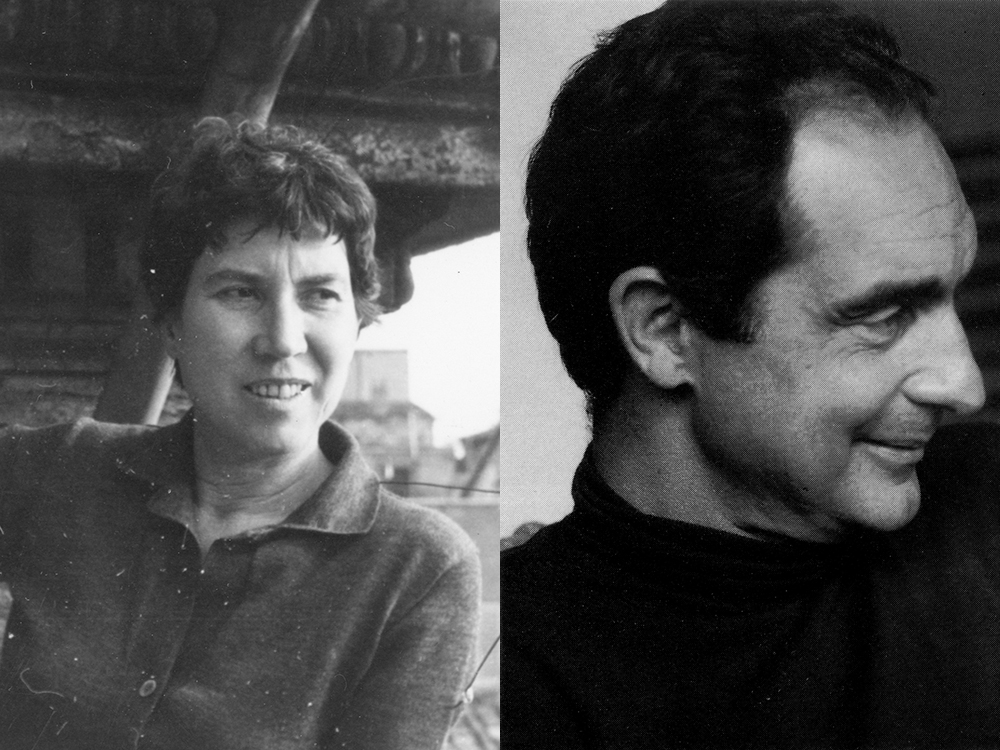

NATALIA GINZBURG AND ITALO CALVINO. GINZBURG PHOTO: COURTESY OF ARCHIVIO STORICO EINAUDI. CALVINO PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S ESTATE.

Natalia Ginzburg, the Last Woman Left on Earth

On September 21, 1947, Italo Calvino—then the twenty-four-year-old book critic for Piemonte’s L’Unitá newspaper—published a review of Natalia Ginzburg’s second novel, The Dry Heart. The review, which is presented below in English for the first time, opens with this proposal: “Natalia Ginzburg is the last woman left on earth. The rest are all men—even the female forms that can be seen moving about belong, ultimately, to this man’s world.” For a moment, if you’re familiar with Calvino’s surreal masterpiece Invisible Cities, written twenty-five years later, you feel as if you’re teetering on the edge of one of that book’s bewildering scenes—all glimpse and symbol, hallucination posing as anthropology. But no, the young writer is merely trying to find the perfect words to describe the entirely singular aesthetic of a novelist who is vexingly (to him, it would seem) female. Calvino’s review stands in the Ginzburg archives as one of the most bizarre, yet also astute, as he pinpoints the way her made-up worlds are hyperrealistic voids, her characters both humane and remote, her Minimalism dependent on small mundane artifacts, her domesticity suffocating and vast. “It’s a shame we’ll never know Ginzburg’s reaction to this review,” the Ginzburg biographer Sandra Petrignani writes, “that positioned her in a new world of fiction, modern precisely because it is ancient.”

Ginzburg is singular, and her organic, turgid, droll, intelligent Minimalism is difficult to capture with descriptives. Her writing just is. Or, as the novelist Rachel Cusk has put it, her voice “comes to us with absolute clarity amid the veils of time and language. Writings from more than half a century ago read as if they have just been—in some mysterious sense—composed.” And though in his review Calvino takes pains to distinguish Ginzburg from the lacy histrionics of women’s writing (take heed, Virginia Woolf), his real point then, and for the next thirty years of their close friendship, was to absolve Ginzburg of the matter entirely: she writes like a man. Ginzburg took his judgment for what it was, a compliment.

Postwar Italian literature, arguably the country’s most fertile literary moment, was dominated by great writers—great male writers. Calvino would soon go on to become one of them, joining the ranks of Cesare Pavese, Alberto Moravia, Elio Vittorini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Primo Levi, and Carlo Levi. The last woman on earth was hardly an outsider. A principal editor at the prestigious publishing house Einaudi alongside Pavese and Calvino (who left journalism for publishing), she was at the heart of a vibrant literary scene. The intellectual lions of this world were stubbornly defined by politics above all else: they were not Jewish writers or Catholic writers, not Holocaust survivors, feminists, depressed writers, or gay writers. They were just writers. If you were to ask them to define themselves as a group, they would have answered antifascist—which would explain nothing about the literature any one of them produced.

In many ways, this school of writers was an antischool. Fiercely united, they read one another’s work, edited and published one another, vacationed and socialized together, gossiped and discussed other writers. Many more times over the years, until Calvino died suddenly of a stroke in 1985, he and Ginzburg would continue to describe each other’s work in print. In a tribute after he died, Ginzburg spoke about reading Calvino through the years. In the first short stories of his that she read, “there flowed vibrant landscapes bathed in sun, though at times the events unfolding were the events of war, of blood and death, nothing ever clouded the great light of day … his style was, from the very beginning, linear and transparent, reality exposed as mottled, variegated, a thousand colors.” Then, right before Invisible Cities, “his most beautiful book,” there was a transformation. “Gradually, the vibrant green landscapes, the glittering snow, the great light of day disappeared from his books. There emerged in his writing a different light, no longer radiant but white, not cold but utterly deserted. His sense of irony was still there but imperceptibly so. He was no longer just happy to exist … it was as if he knew that his capacity to search, excavate, contemplate had abandoned him forever.” Calvino turned his gaze elsewhere, she wrote, trying to explain Calvino’s reach for transcendence, “to the immensity of human events.”

Natalia Ginzburg was thirty years old when she met Calvino; he was twenty-three. She was already a war widow with small children, and The Dry Heart had not yet been published. He’d stopped by the Einaudi offices to pick up books to review for L’Unita. The two stood in the hallway in front of a radiator, near a couch, talking. Ginzburg wrote, “I remember the radiator perfectly, the snow falling outside, but I can’t remember what we talked about.” They probably talked about Hemingway, she thought, about the story “Hills Like White Elephants,” which, they both agreed, they “would give ten years of life to have written” themselves. They couldn’t have imagined that winter day in 1946 when they, still strangers, would soon meet their hero together. That he would sit with them around a table and give them writing tips. That Hemingway would then read Ginzburg’s books and send word that he thought “they were glorious.” They couldn’t have imagined the friendship, the life in letters, that stretched years into the future. Below, I have translated Calvino’s 1947 review into English for the first time. —Minna Zallman Proctor

Natalia Ginzburg is the last woman left on earth. The rest are all men—even the female forms that can be seen moving about belong, ultimately, to this man’s world. A world where men make the decisions, the choices, take action. Ginzburg, or rather the disillusioned heroines who stand in for her, is alone, on the outside. There are generations and generations of women who have done nothing but wait and obey; wait to be loved, to get married, to become mothers, to be betrayed. So it is for her heroines.

Ginzburg comes an outsider to a world in which only the most conventional signs, tracing from an ancient era, can be deciphered. From emptiness there emerges, here and there, an identifiable object, a familiar object: buttons, or a pipe. Human beings exist only according to schematic representations of the concrete: hair, mustache, glasses. You can say the same about the emotions and behaviors; they reveal nothing. She doesn’t reveal so much as identify already-established words or situations: Ah ha, I must be in love … This feeling must be jealousy … Or, now, like in The Dry Heart, I will take this gun and kill him.

And yet Natalia Ginzburg is a strong woman. By which I mean a strong woman writer. The burden of which hangs, like a condemnation, over her books. And yet her acquiescence to such a burden does not make her language earnest, sentimental, or evasive. There is no womanly capitulation to the flurry of sensations or intermittent tricks of memory you find in Virginia Woolf, then imitated by other women writers, even Italian women writers.

Natalia Ginzburg believes in things, those scarce items that can be ripped from the vacuum of the universe: the mustache, some buttons. She believes in her feelings, in her actions, whether kind or desperate.

Whosoever has said that, because of the raw nakedness of Ginzburg’s language, she is influenced by the Americans, is being simplistic. The prose lineage she belongs to is that of open eyes, all scene, one where human connection is tacit. It is a great lineage, one that links Maupassant to Chekhov, and Chekhov to Mansfield. But young Katherine Mansfield knew how to play with sadness as well as boredom. Natalia Ginzburg doesn’t play; she surprises, she dreams. Moreover, as interwoven as they are with echoes of place, her novels invite association with the great women writers of Italian realism, Grazia Deledda, Caterina Percoto.

Ginzburg writes in the first person, on behalf of characters who are profoundly remote. Hers is not the first-person of lyrical diary keeping, but rather an externalization in which she participates body and soul. Deep down, however, she is still the same bored and lonely woman who never seems to find, or even bother to seek, meaning in her life. The proletarian girl from her first book, The Road to the City, who doesn’t know how to protect herself from emotions, whether her own or those of others, is refashioned in Ginzburg’s second novel, The Dry Heart. Here is a middle-class teacher, at first lonely and waiting to find a husband, then trapped in the disappointment of a bad marriage. The restless need for redemption that appears in the first novel as a longing for the city destined to fade, incarnates now as murder, a gesture of ultimate desperation.

That is how it ends, but the ending comes at the beginning. The novel opens with the crime: “And I shot him between the eyes.” After which the heroine sits on a park bench and recounts how she got to such a point and then turns herself in. To tell the story here would deprive you of the flavor, the stern clarity that drives the story right through, unfaltering, to the end—that’s the reason that you have to read it all in one sitting.

—Translated from the Italian by Minna Zallman Proctor

Italo Calvino (1923–1985) attained worldwide renown as one of the twentieth century’s greatest storytellers. Born in Cuba, he was raised in San Remo, Italy, and later lived in Turin, Paris, Rome, and elsewhere. Among his many works are Invisible Cities, If on a winter’s night a traveler, The Baron in the Trees, and other novels, as well as numerous collections of fiction, folktales, criticism, and essays. His works have been translated into dozens of languages. Read his Art of Fiction interview.

The author of Landslide and the editor of The Literary Review, Minna Zallman Proctor won the PEN/Renato Poggioli Award for her translation of Federigo Tozzi’s Love in Vain. Most recently, she translated Natalia Ginzburg’s Happiness, as Such (New Directions, 2019).

No comments:

Post a Comment