|

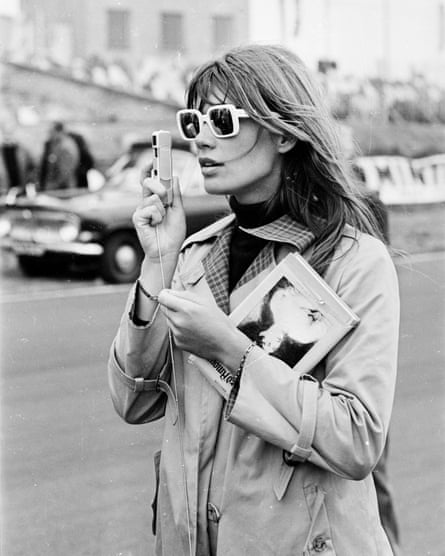

| Francoise Hardy at Brands Hatch during the filming John Frankenheimer’s 1966 racing drama Grand Prix. Photograph: Victor Blackman |

INTERVIEW

Françoise Hardy: ‘I sing about death in a symbolic, even positive way’

Françoise Hardy is reciting the first lines of Serge Gainsbourg’s song La Javanaise for my benefit. We are sitting at a small table in the middle of an otherwise empty room in a stylish Paris hotel. Eyes closed, her hand tracing a repeated arc in the air, she enunciates every word as if teaching a hapless pupil – “J’avoue j’en ai bavé, pas vous…” she intones softly, “Avant d’avoir eu vent de vous…”

These seductive lines, she says, are the perfect example of the “sonority” of a song lyric, the elusive element she values above almost all else in her music. “For me, everything begins with the melody,” she says, growing animated. “Without the melody, there can be no words, but I also need this sonority, this poetic sound that the words make when they combine with the melody. This has always been my obsession. I know that I am very limited vocally, but I also know why I am still here – it is purely because I am so selective when finding the melodies.”

As the sad, sonorous songs on her new album, Personne d’Autre, attest, Françoise Hardy is very much still here. At 74, she occupies a singular place in pop culture, being both an enduring style icon – in January this year, Vogue celebrated her birthday with a feature entitled “10 style lessons to take from Françoise Hardy for the season ahead” – and a singer whose songs have lent themselves to constant re-evaluation by several generations of fans and critics alike. She has collaborated with Blur and Iggy Pop and has a fondness for the music of the Jesus and Mary Chain and cult Brooklyn band Cigarettes After Sex, whose sound, she says, “I have been looking for all my life”. She cites her 1971 album, La question, a collaboration with the late Brazilian musician Tuca, as her personal favourite of her own recordings, and it remains a classic among her fans for its lyrical sensuality and sophisticated arrangements. Her songs and her limited voice have taken her further than she ever expected to go, given that she was a somewhat reluctant pop star from the start, a singer who hated many of the early recordings that made her name.

Hardy shot to fame in the mid-1960s with a million-selling debut single, Tous les garçons et les filles, a song whose chorus, I suggest, had that lyrical sonority she rates so highly. “Oh no!” she exclaims, looking momentarily horrified. “I was so young then and untutored. I did not know anything about this stuff. Absolutely nothing. Some of those early songs are just terrible. At that time, musical sophistication was really very far from my mind.” Nevertheless, the hit singles flowed throughout the decade, she released a dozen bestselling albums in France, and her face appeared on Paris Match and other magazines so regularly that she became the French cover girl of the 1960s.

Fifty years on, she still exudes a quintessentially French elegance. She is dressed in a simple black T-shirt and tailored black jacket over dark blue jeans. Her signature fringe and long hair having long since given way to a chic, snow-white bob, and a crimson silk kerchief offsets her ivory pale skin. There is a calmness about her that is palpable and perhaps spiritual – in response to my proffered hand, she responds with a Zen-like bow, her hands clasped together as if in prayer. She is a survivor in more ways than one, having come through a long battle with lymphoma that, four years ago, saw her taken to hospital in a coma after a fall. Her life hung in the balance for several weeks until, with her son’s permission, the doctors tried a new kind of chemotherapy. Last year, in a television interview, she spoke of her almost miraculous recovery with mixed feelings: “I regretted waking up because I almost had the death I was dreaming about. So the question I asked myself when I woke up was: ‘Why this reprieve?’”

Today, she looks thin but healthy, her eyes radiating a quizzical alertness that can be almost unsettling when she occasionally fixes you with a slightly reproving stare. “I don’t really like what journalists do with what I tell them,” she tells me as if by way of warning, “but it’s not a problem and, anyway, it makes for an entertaining break.”

Hardy’s new album is an unapologetically melancholic affair, that sonorous voice delivering songs that, in her characteristically impressionistic way, articulate love lost, regret and mortality. “Time is accelerating nowhere,” she sings on Un seul geste (A Single Gesture), while both Train spécial and Le large (Sail Away) sound like wistful goodbyes. Is it an album about growing older? “Not intentionally,” she says after a pause, “but, in a way, yes, since that is what is happening. I always write about the same subjects, but when you are 74 you become more reflective. Also, you cannot sing the same kind of lyrics as when you were 20 or 30. That would be somehow undignified. For some people, of course, it does not matter, but for me it does.”

There are a couple of songs, I suggest, that seem to deal directly with mortality and her acceptance of the same. “Yes,” she says, “but I sing about death in a very symbolic and even positive way. There is an acceptance there, too. For instance, there is a song called Special Train, which I like very much, but at my age, I can really only sing about that one very special train that will take me out of this world. But, of course, I am also hoping that it will send me to the stars and help me discover the mystery of the cosmos.” (Hardy’s other abiding interest is astrology: she has written two books on the subject and also gives readings based on an individual’s astrological birth charts.)

On other songs, particularly the regretful A cache cache (Hide and Seek) and the plaintive Seras tu la? (Will You Be There?), written by the late Michel Berger, she seems to be addressing her lyrics to an absent partner. She mulls this over for a long moment. “They are maybe not directed at someone in particular,” she says, “but often I think of the past I had with my husband. What inspires me is a mixture of the memories of the past I had with him and the feelings I have today.” She is referring to the 1960s pop heart-throb turned actor Jacques Dutronc, from whom she is separated but not divorced, and who spends most of his time in their Corsican villa. They have a son, Thomas, who is an accomplished guitarist and her sometime collaborator. “The songs are not always biographical,” she elaborates, “but sometimes the melody can take you to places you did not mean to go – or even want to go.”

From the very beginning of her career, Hardy exuded an indefinable otherness, which set her apart from her contemporaries, singers like Johnny Hallyday and France Gall, whose manufactured sound defined the yé-yé style that characterised French pop in the early 1960s. Her songs, however jaunty they sounded, often evinced a kind of dreamy sadness – “I walk down the streets, my soul in sorrow” runs a line in her debut hit single, Tous les garçons et les filles. That wistfulness contrasted nicely with her perfectly pitched style, poise and captivating beauty. It was a combination that caused a generation of male adolescents on both sides of the Channel to fall head over heels in love with her – or, more precisely, with the idea of her that the songs suggested. That she seemed to be blithely unconcerned by their adoration, and apparently unaware of her own beauty, only added to her allure.

Hardy’s classic record covers from the 1960s, styled and shot by her then partner, photographer Jean-Marie Périer, often feature her unsmiling face, hair falling over her shoulders, eyes fixed on some distant point beyond the camera. Though she did not hang out with the bohemians and intellectuals of the rive gauche, there was nevertheless something about her persona that chimed with the romantic existentialism of the time. In 1966, Jean-Luc Godard cast her in a cameo in Masculin féminin, a defining New Wave film brimming with contemporary pop culture references, from Bob Dylan to James Bond. As her fame grew, she drew the attention of Mick Jagger, who described her in an interview as his ideal woman, and Bob Dylan, who included a beat poem to her on the sleeve of his fourth album, 1964’s Another Side of Bob Dylan – “for françoise hardy/at the seine’s edge/a giant shadow/of notre dame/seeks t’ grab my foot/sorbonne students/whirl by on thin bicycles...” For women, she was a role model of a different kind. “There was a French singer, Françoise Hardy,” the New York-born singer-songwriter Carly Simon recalled later. “I used to look at her pictures and try to dress like her.”

Her otherness, Hardy says, began in childhood. Born in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1944, her early years were marked by an absent, emotionally withdrawn father, and a mother who, she says, “lived the life of a nun”. In the immediate postwar years, after her parents’ separation, her mother worked long hours to pay for her daughter’s convent education. “My mother was a solitary figure who did not really have any friends,” she tells me, matter-of-factly. “At the weekends, my sister and I were sent to my grandparents’ house and that was it. The atmosphere was so strict and there was a lot of shame perhaps to do with my parents’ separation. My grandmother told me repeatedly that I was unattractive and a very bad person, which makes you think as a child that you will never meet anyone. It is hard even now for me to understand why she was like that.”

Was pop music initially an escape from that cloistered, claustrophobic family dynamic? “No, it was more what we call in France a coup de foudre [thunderbolt] in every sense of the word. It was unexpected and it was love at first sight.” She recounts how her mother pressurised her absent father to buy her a gift as a reward for excelling at the baccalaureate [the French school diploma]. “I was younger than any pupil in my year and yet I somehow achieved the highest marks.” At that time, in her mid-teens, she was “obsessed” with Radio Luxembourg, listening nightly to the pop songs it broadcast from Britain and America, in thrall to the stars of the pre-Beatles era: Elvis, Brenda Lee, Rosemary Clooney, Marty Wilde, Billy Fury and Cliff Richard. “I will never know why I chose a guitar because a transistor radio was all I ever wanted,” she says, still looking perplexed. “Plus, I knew absolutely nothing about how to play the guitar, so I was astonished to find that I could make so much from just three chords.” She began writing songs obsessively in her bedroom, sometimes knocking out three or four in a week. “Really, those three chords produced most of my songs for the next 10 years.”

Despite her acute shyness and lack of confidence, she willed herself to attend an open audition hosted by Pathé Marconi, then France’s premier record label. “It’s difficult to explain,” she says, frowning, “but even though I did not think I was very good, I somehow needed to have that confirmed. I needed to be told that I should give up. Also, I knew that if I did not take this chance, however humiliating the result might be, that I would regret it for the rest of my life. That is really how I found the courage to go.”

The audition was not a success, but neither was it the failure she anticipated – “I left feeling so happy that I had not been thrown out quickly.” She persevered, attending other auditions and soon afterwards, in 1961, she was offered a contract by the Disques Vogue record label. Her initial studio session lasted less than four hours and produced five finished songs. To her horror, the label chose a lightweight pop confection, Oh oh chéri, composed by Johnny Hallyday’s songwriting team, as the A-side of her debut single. But it was her self-penned song, Tous les garçons et les filles, that the radio stations and the public responded to. Released in 1962, it sold 2m copies in France and in Britain it just failed to make the top 20. Suddenly, aged 18 and still a shy convent schoolgirl at heart, Hardy became France’s biggest pop star. “I listened to that record and I was so dissatisfied,” she says, “and I have been dissatisfied very often ever since.”

In 1963, her frustration with the formulaic nature of French pop was such that she insisted on recording in London. There, she found a producer, Charles Blackwell, and a group of session musicians who listened to what she had to say. “I was happy from that moment,” she says. “I was free to make another kind of music, not this mechanical music I had been trapped in.” She returned to London over the next few years to record and also to play a concert at the Savoy, where she made one of her last ever live appearances in 1968. “If I could sing like Céline Dion, it would have been different,” she said years later.

In London, too, she mixed with the new pop royalty, having dinner “with two Beatles” and receiving regular visits at her hotel from a smitten Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones. Her then partner, Jean-Marie Périer, knew everyone on the London pop scene, but was seldom around due to his busy schedule. “I think I was a source of fascination for the English pop musicians,” she says, laughing her still girlish laugh. “I heard much later that there was a rumour that I was a lesbian, but really I was just shy and unsure. When Brian Jones introduced me to his girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg, I was very flattered and charmed, but then I heard that they were each trying to figure out which one of them I was interested in sexually. Of course, this was the very last thing I was interested in. I was unbelievably innocent.”

In Paris, in 1966, two years after Dylan had penned his mysterious poem to her, she famously crossed paths with him when he played the Olympia theatre on his first electric tour. Afterwards, she and Johnny Hallyday went to a gathering in Dylan’s suite at the opulent George V hotel. “It was truly a shock to see him,” she says, still looking perturbed after all these years. “He looked even worse than he did backstage. So thin, so pale, so strange. I honestly thought he did not have long to live.”

At one point, a very strung-out Dylan beckoned her into his bedroom, where he placed his latest record, Blonde on Blonde, on the turntable and played her two songs: I Want You and Just Like a Woman. His intentions, I suggest, could hardly have been clearer. “I know,” she says, hooting with laughter, “but I was too busy listening intently to the songs, which sounded like something entirely different to anything I had heard before. Plus, I was so impressed and petrified to meet him. Maybe if he had sung the songs to me, I would have got it.”

She then tells me a remarkable story. A few years ago, she says, an American couple made contact with her after years of trying. Back in the 1960s, they had owned a cafe in New York where Dylan used to go daily to compose lyrics. They told her that he had left behind some typewritten drafts, and two of them were letters about her. She now has them in her possession. “So, this is how, only a year or so ago, I realise that in the early 60s, Bob Dylan maybe really had a romantic fixation on me – as only young people can have.”

Can she reveal anything of what he wrote to her? “Oh, no, no. Never could I do that. I can say that the two drafts are very moving, but I cannot reveal what they say. Also I don’t understand everything of what he has written. I do think, from the poem he wrote, which I did not take too seriously at the time, and now these letters, that I had quite a place in his mind at that time and even in his heart. I think maybe I was very serious for him. And, it moves me very much.”

Françoise Hardy still remains something of an enigma, a singer still unconvinced of her singular gift and the effect it has had on those who fell under her spell. “It has always been a big surprise to me that people, even very good musicians, were moved by my voice,” she says. “I know its limitations, I always have. But I have chosen carefully. What a person sings is an expression of what they are. Luckily for me, the most beautiful songs are not happy songs. The songs we remember are the sad, romantic songs.”

Personne d’autre is out now on Parlophone France

No comments:

Post a Comment