|

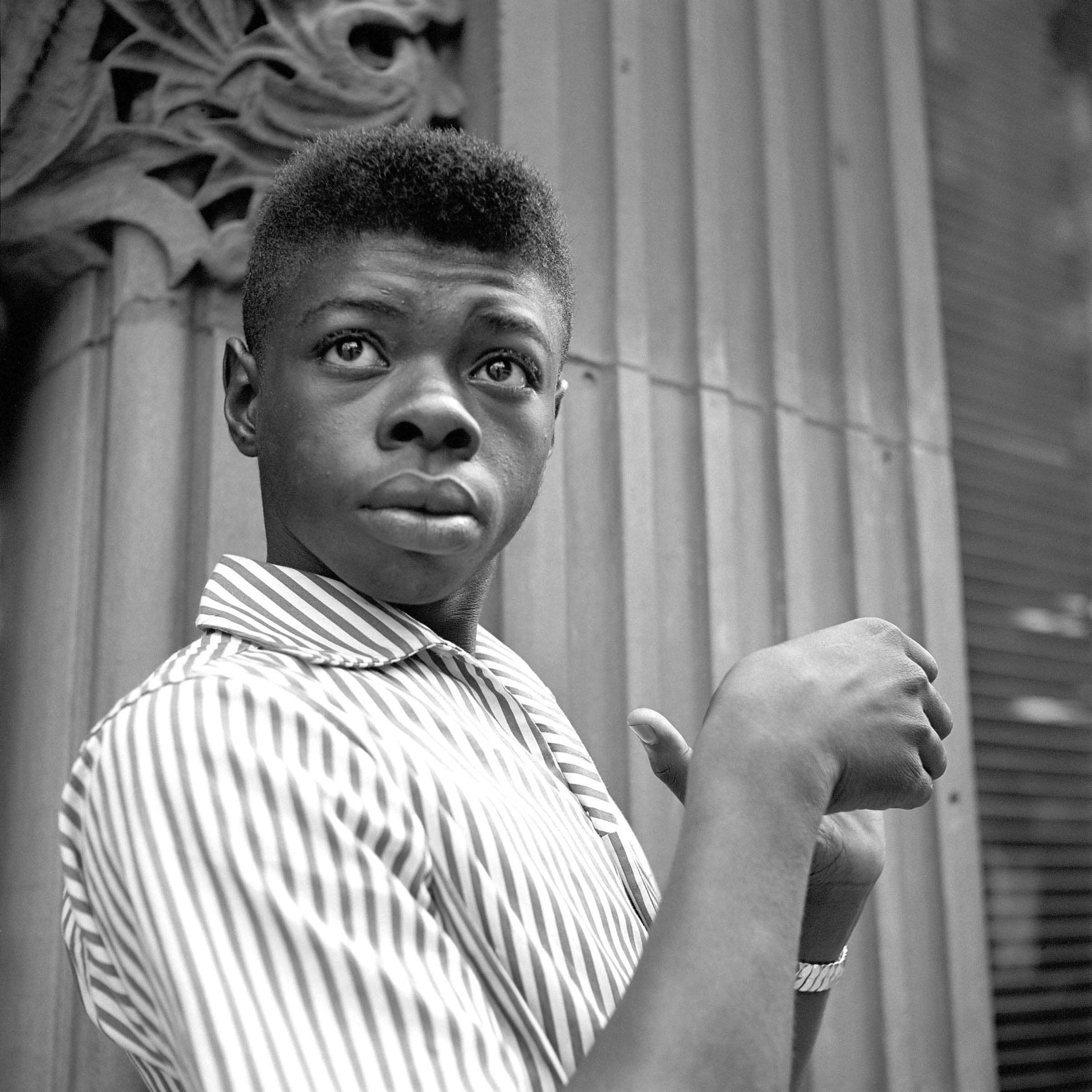

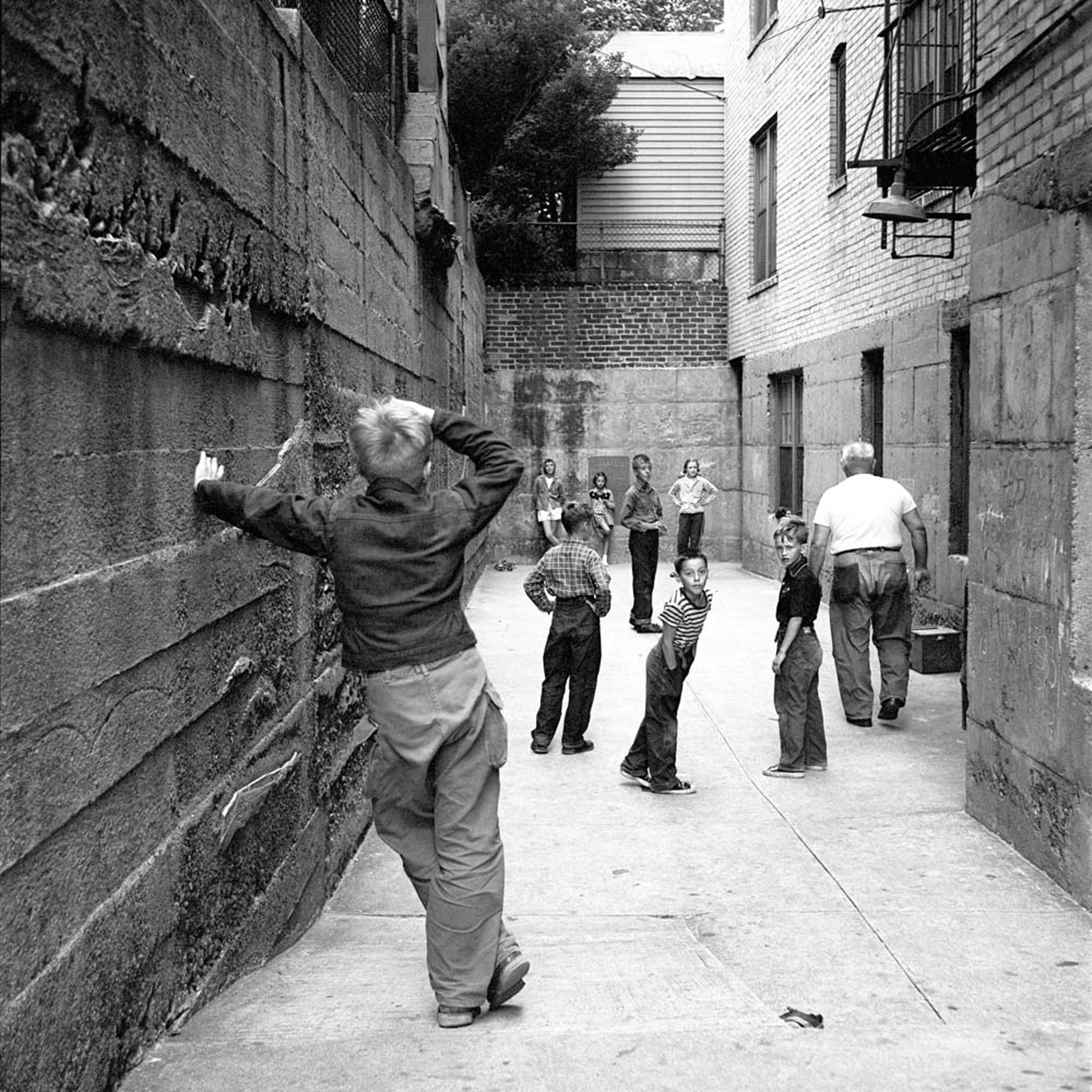

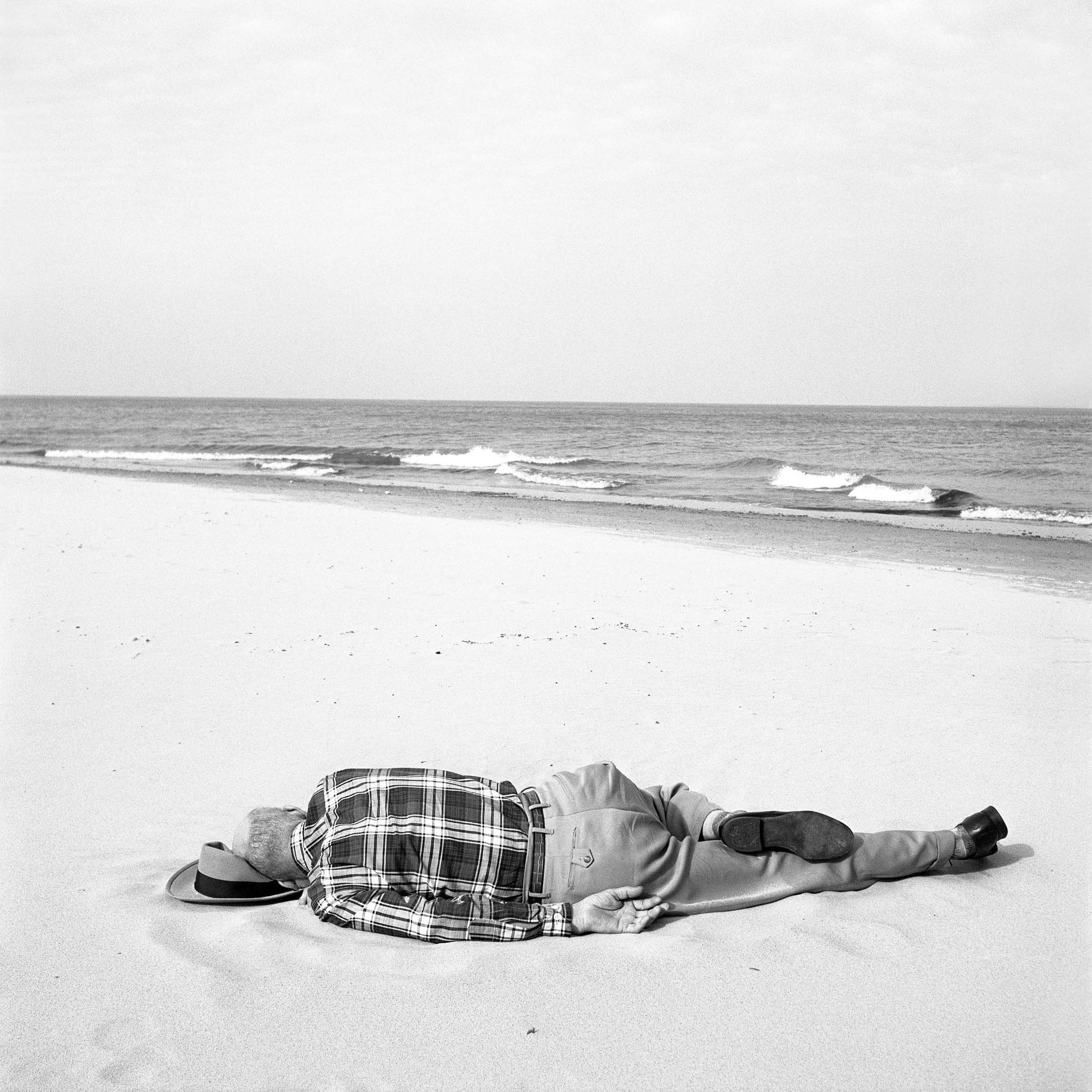

| Photo by Vivian Maier New York, 4 December 1954 |

Vivian Maier, the secret photographer

She cradles a Rolleicord camera to her breast, her eyes staring into her reflection. Until recently, the woman behind the camera was unknown, living a quiet life as a nanny in Chicago and dying, alone in a nursing home, in 2009 at the age of 83. When Vivian Maier’s cache of 100,000 images were unearthed, her work was compared with the greats of street photography. A film was made, Finding Vivian Maier, which introduced a new generation to her work. But Maier herself was the draw; who, exactly, was the mysterious French nanny? What drove her relentless imagery, and why did she keep it so resolutely hidden?

Maier was a private but eccentric Mary Poppins-like figure, who spoke with a delicate French trill and was never without her medium format camera. She took thousands of photographs from the 1950s to 70s, but squirrelled them away in a room she forbade anyone to enter. She was poor, and in 2007 her possessions were auctioned off to recoup her debts – her archive of photographs among them. John Maloof, an estate agent and president of his local history society, discovered them at an auction and took a punt, hoping to find images for a book he was writing on the Portage Park area of Chicago. He found nothing relevant, and put the whole lot into storage for two years.

“I was one of the few buyers at that auction,” he remembers. “I Googled ‘Vivian Maier’ and nothing came up. It wasn’t until 2009, when I found a lab envelope with her name on it, that I was prompted to Google her name again. What came up was an obituary posted only a few days prior. Ever since, Vivian has become my life.”

Maloof has what is believed to be the bulk of Maier’s work and personal effects. But there are more negatives, prints, films, and tens of thousands of undeveloped rolls. Some of these belong to Jeff Goldstein, a Chicagoan who set about acquiring the items Maloof didn’t get. He set up an “educational and collaborative space” dedicated to Maier’s work, while Maloof is now working on a documentary and book about Maier’s life and photography.

Maier was born in New York City on 01 February 1926 to a French mother and an Austrian father, and spent her childhood shuttling between America and France. “Around 1930, her father disappears from records,” recounts Maloof, in a broad Chicago twang. “She and her mother are recorded as living with an award-winning portrait photographer named Jeanne Bertrand, who was born in the 1800s and knew the founder of the Whitney Museum. Vivian may have had some artistic influence rub off on her in these early years.”

In around 1959, Maier packed her collection of medium format cameras in a large hard case and set off around the world for a year, on a trip that Maloof says was more than just a holiday. “I think this was her exploring,” he reckons. “Thailand, Egypt, Yemen, Italy, France, Taiwan, Vietnam, Morocco, Canada, the Philippines – she was everywhere. She was independent and intrepid, a very private, yet opinionated and strong woman.

“If you had Vivian Maier as a nanny, she would be the coolest adult you’d know,” he adds, referencing conversations he’s had with some of her former charges. “The kids all wanted to be with Vivian. She was a real eccentric who’d take kids on wild adventures exploring the city, take them to shows and plays and strawberry fields. If she found a dead snake on the kerb, she’d take it home and show them. And she always had her camera around to document this. As a kid, that’s pretty cool.”

Maier worked as a governess until the mid-1990s, never marrying or having children of her own. Taciturn to the point of silence, she gained a reputation for being secretive. “I think Vivian was so secretive because she was a nanny with no ties to any family, no close friends, never married, never had kids,” explains Maloof. “From what I know, she never had a love life. Photography was the only thing she had. And if you expose your only emotional outlet, it’s vulnerable. If she knew people would receive it they way they are today, she may have thought twice. But hindsight is always 20/20.”

Now that her work has been discovered, Maier’s legacy is secure. “Every street photography book will have to include her from now on,” says Deutsche Borse Photography Prize nominee Anna Fox. “In the history of photography, lots of people have been discovered after their deaths, but her photographs are amazing. I was quite taken aback when I first saw them. What’s most interesting is the accidental story and the incredible effort to get her work off the ground – because there’s little about her background and people that knew her, it adds to the mystery and intrigue. But the images are beautifully constructed and it’s clear she knew her references. There’s a glimmer of Diane Arbus, a glimmer of Robert Frank.”

Maier could have gleaned this knowledge from her large library of art and photography books, but there’s no record of her being formally trained and, as far as Maloof is aware, she never received any feedback from critics or experts. Despite this, she left a secret archive of masterful photographs behind – something which, for Fox, is typically female. “It’s a common story that only small amounts of photographic work by women gets out into the public,” she adds. “Despite the vast female majority of photography teachers and students, it’s still a male-dominated profession. Exhibitions and publications hardly reference women photographers. It can change, it will have to change.

“As a woman you have a privileged position,” she continues. “Women develop relationships with people they are photographing, and are less threatening with a medium format camera. There’s a subtle irony and gentleness that is a particular female gaze, although it makes more sense to look at photographers as photographers. Vivian’s images are so strong they stand up regardless of gender.”

It’s impossible to know how Maier felt about her obscurity, but her images sensitively record life’s have-nots and also-rans. More gentle than the work of Arbus, they bleed with empathy, retaining a respectful distance even as they hone in on outsiders’ private moments. She captures the faraway gaze of a young man caught in thought and the taut expression of a middle-aged woman sneaking a look at a disabled man, but the faces she records are always sombre. It’s always a film noir in Maier’s world.

And if Maier picked out obscure people and faces, she also picked out seemingly nondescript locations, even in America’s most photographed places. Having grown up in Chicago I’m all too aware of the visual clichés of the city, including offset skyline shots, skyscrapers in perspective at sunset and the bustling urban scene outside the flashing lights of the Chicago Theatre. Maier does none of these, capturing the city in a subtler way. “There’s always been an interest in street photography in Chicago, the city’s made for it,” informs Joe Gallina, manager at the Central Camera store where Maier processed her rolls. “But Vivian’s style stands out because she really captured the city. Her pictures are a social history.”

In December 2008, Maier slipped and fell on the ice. She never truly recovered and died on 21 April the following year in a suburban nursing home. While she was still alive, someone – it’s thought Maier herself – recorded her thoughts on life and death. Although the sound is tinny there’s a striking confidence in her voice. “Nothing is meant to last forever,” she says. “We have to make room for other people. It’s a wheel. You get on, you have to go to the end, and somebody has the same opportunity to go to the end, and so on. And somebody else takes their place.”

She could be talking about her own photography, which so nearly sank into obscurity. No doubt her work will also inspire other photographers to take up their cameras and get out into the streets; for now, it’s just good to celebrate her remarkable achievement. The writer Franz Kafka asked his friend Max Brod to destroy all his unpublished works after he died – an order Brod ignored. Vivian Maier may never have intended her work be seen by anybody, but by sharing the delicate power of her images, John Maloof, Jeff Goldstein and others have opened a photographic treasure trove.

See more of Maier’s work here or watch the film here.

Read our article about a new book of Maier’s colour photography: https://www.1854.photography/2018/11/vivian-maier-the-color-work/

No comments:

Post a Comment