Jewelry has been a form of visual communication from the start of human history, and from the beginning it has always assumed a form of personal adornment while it projected a type of status symbol up to the position of kings and emperors. It is likely that from an early date Jewelry was also worn as a protection from the dangers of life, and as a conduit for dealing with mystical aspects of culture. Jewelry made from shells, stone and bones has survived from prehistoric times. In the ancient world the discovery of how to work metals was an important stage in the development of the art of jewelry. Over time, metalworking techniques became more sophisticated and decoration more intricate. In many cultures, as we shall see, jewelry was frequently included in burials and at times was offered to various temples by believers. The contextual information uncovered through excavations provides important clues about beliefs, customs, cultures, relationships, and the use of jewelry as talismans. Of course, one has to be extremely careful in these types of analysis, as Megan Cifarelli(2009) has argued at times various exhibitions provide misleading information. For example, in the absence of detailed contextual information for the following Mesopotamian necklace an exhibition text was focusing on"the use of materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, shell, and agate" Cifarelli argues:

Much archaeological jewelry comes from tombs and hoards. The best-known ornaments in early Neolithic graves in central Europe are those of the marine spondylus shell, imported from the Aegean, or to a lesser extent from the Adriatic coast. These ornaments are clearly connected to the richest burials and must have been of extremely high value. They are the most important evidence of long-distance connections through Europe in early to middle Neolithic times (Séfériades 1995; Müller 1997; Kalicz and Szénászky 2001).

Today, the Akan tradition in Ghana in Africa still believes in life after death – Saman Adzi, where one continues life in relative luxury to when living. This is why families bury their dead with basic items like clothing, jewellery, hankies and money for the journey into the next world. Other burial items differ from family to family. As early as the 15th century, European merchants wrote about the richness of African gold objects used for adornment and intended for public display. Gold deposits were discovered in all regions of Africa, and became the most important commodity during pre- colonial times. The region of the Akan, spreading from the forest zone and costal areas of Ghana to the southern shores of the Ivory Coast, is the richest auriferous zone in West Africa. Several individual tribes make up the Akan people, the Asante and Baule being among the most famous, all united by their common ancestry and language. The royal courts of the Akan people were reportedly the most splendid in Africa. Oral tradition and iconography in Akan works of art are very closely connected. Verbal and visual symbolism tells stories or proverbs. Imagery of royal power on court ornaments carry out messages that helps keep the balance and continuity within the society.

Burying valuable objects with the dead has also been a practice in China and other Asian countries for several thousand years. In addition to gold, silver and other valuables, burial objects include daily necessities, arts and crafts, the four treasures of study (writing brush, ink stick, ink slab and paper), books and paintings, tools of production and scientific and technological devices, and these have turned many tombs into priceless underground treasure houses, telling the vogues of the times. At the Cambodian sites of Vat Komnou/Angkor Borei (Takeo province) and Village (Kampong Cham province) about 100 burials of the 4th century BC to the 2nd century AD with many offerings have been discovered.

Further, about 50 burials excavated at Go O Chua in Long An province in southern Vietnam provide additional information from the late phase of the Pre-Angkor period. With its unusually rich offerings, the burial site of Prohear surpasses all expectations. The burial sites of this region show clear cultural similarities (e.g. high pedestalled bowls of the same shape and ornamentation), but also display strikingly distinctive local features. Thus, the wealth of gold offerings is without comparison at any other burial site of the early Iron Age period in this region and the great number of bronze drums from the site - although mostly undocumented - is hitherto unique for the southern parts of mainland Southeast Asia, far away from the Dong Son cultural area.

In 2003, an archaeological expedition dug up a burial mound in the Shiliktinskaya Valley to find a Golden Man – a presumed leader of the Saka tribe, a branch of the Scythian nomads that populated Central Asia and southern Siberia in the 1st millennium BC. The pagan Saka fought the ancient Persians, and grew rich through trading across the great steppes of Central Asia. Some of their wealth ended up in the tombs of their chieftains, who were buried wearing jewelry and gold-plated armor – like the man in the Shiliktinskaya mound, the third such find in Kazakhstan since 1970.

The Bronze Age civilization that flourished on the Mediterranean island of Crete is known as the Minoan. Because Crete lay near the coasts of Asia, Africa, and the Greek continent and because it was the seat of prosperous ancient civilizations and a necessary point of passage along important sea-trading routes, the Minoan civilization developed a level of wealth which, beginning about 2000 bce, stimulated intense goldworking activities of high aesthetic value. From Crete this art spread out to the Cyclades, Peloponnesus, Mycenae, and other Greek island and mainland centres. Stimulated by Minoan influence, Mycenaean art flourished from the 16th to the 14th century. Middle Minoan period, in Greece, when rapid social changes took place, with palaces emerging for the first time, but also being destroyed and having to be rebuilt. The Minoan society was changing rapidly and the people associated with the palaces needed consensus from the larger population, to affirm their social ranking and maintain control.

The emerging social tensions increased the power of religion as a stabilizing force for maintaining the social structural of order. The recurring iconography of a Minoan goddess descending on a throne seems to became a key symbol of the legitimization of the new social order. In the Bronze Age, Mycenaean people had strong spiritual beliefs about an afterlife and the fact that we are seeing bodies that have been embalmed and items buried with them, gives evidence for this. They believed that once you die, your body needs to be respectably buried for it to be able to move on and that you also needed objects from the material world to take up with you in the after life. This was not only for use in the afterlife, but they thought that to get to the afterlife, you had to cross a river that charged a fare, so if you did not have items to pay, then you would not get to go to the next life. A profusion of gold jewelry was found in early Minoan burials at Mókhlos and three silver dagger blades in a communal tomb at Kumasa. Silver seals and ornaments of the same age are not uncommon.

The first evidence of jewelry making in Ancient Egypt dates back to the 4th millennia BC, to the Predynastic Period of along the Nile River Delta in 3100 BC, and the earlier Badarian culture (named after the El-Badari region near Asyut) which inhabited Upper Egypt between 4500 BC and 3200 BC. From 2950 BC to the end of Pharaonic Egypt at the close of the Greco-Roman Period in 395 AD, there were a total of thirty-one dynasties, spanning an incredible 3,345 years!

As the exhibition text indicates, none of these materials was available locally, suggesting that they were valued not just for their beauty but because they were difficult to obtain. Gold, lapis lazuli, and carnel;ian were imported as raw materials: gold from Anatolia, Iran, and Egypt; carnelian from Iran and Indus Valley; lapis from the Badakhshan region of what is now Afghanistan. Two types of carnelian beads, those etched with alkali and long, biconical tubes, were likely crafted at Indus Valley Sites (...) Excavators have often published finds of beads as reconstructed "nrcklace" without articulating any rationale for the reconstructions, and these hpothetical reconstructions are perpetuated by scholars and museum displays. One such 'necklace is highlighted in the Mesopotamia case; it is a symmetrical grouping of beads typical of the late Early Dynastic period / Akkadian era and consisting of gold tubes, lapis lazuli in biconical and globular forms, long biconical carnelian tubes, etched and plain carnelian barrels, and carnelian lentoids etched with a white ring. Despite the persistent necklace reconstruction, paralles from Mohenjo Daro and possibly Ur suggest that these weighty carnelian tubes were used for hip and waist gridles rather than necklace..

|

Mesopotamian carnelian, lapis lazuli, and gold beads, restored as a necklace, mid third millennium BC from Irak, Kish. Chicago, The Field Museum of Natural History. |

|

| Native American Indian ring |

|

Native Indian American jewelry |

|

African beads, jewelry and crafts |

|

African bridal jewellery |

.  |

| African Collar |

Much archaeological jewelry comes from tombs and hoards. The best-known ornaments in early Neolithic graves in central Europe are those of the marine spondylus shell, imported from the Aegean, or to a lesser extent from the Adriatic coast. These ornaments are clearly connected to the richest burials and must have been of extremely high value. They are the most important evidence of long-distance connections through Europe in early to middle Neolithic times (Séfériades 1995; Müller 1997; Kalicz and Szénászky 2001).

|

Elite gold jewelry in the La Tène style from a 'chieftain's' grave at Waldalgesheim, in the Rhineland, Germany |

Today, the Akan tradition in Ghana in Africa still believes in life after death – Saman Adzi, where one continues life in relative luxury to when living. This is why families bury their dead with basic items like clothing, jewellery, hankies and money for the journey into the next world. Other burial items differ from family to family. As early as the 15th century, European merchants wrote about the richness of African gold objects used for adornment and intended for public display. Gold deposits were discovered in all regions of Africa, and became the most important commodity during pre- colonial times. The region of the Akan, spreading from the forest zone and costal areas of Ghana to the southern shores of the Ivory Coast, is the richest auriferous zone in West Africa. Several individual tribes make up the Akan people, the Asante and Baule being among the most famous, all united by their common ancestry and language. The royal courts of the Akan people were reportedly the most splendid in Africa. Oral tradition and iconography in Akan works of art are very closely connected. Verbal and visual symbolism tells stories or proverbs. Imagery of royal power on court ornaments carry out messages that helps keep the balance and continuity within the society.

|

Akan Gold Bead Necklace |

|

18th century African Beaded Necklaces |

Burying valuable objects with the dead has also been a practice in China and other Asian countries for several thousand years. In addition to gold, silver and other valuables, burial objects include daily necessities, arts and crafts, the four treasures of study (writing brush, ink stick, ink slab and paper), books and paintings, tools of production and scientific and technological devices, and these have turned many tombs into priceless underground treasure houses, telling the vogues of the times. At the Cambodian sites of Vat Komnou/Angkor Borei (Takeo province) and Village (Kampong Cham province) about 100 burials of the 4th century BC to the 2nd century AD with many offerings have been discovered.

Further, about 50 burials excavated at Go O Chua in Long An province in southern Vietnam provide additional information from the late phase of the Pre-Angkor period. With its unusually rich offerings, the burial site of Prohear surpasses all expectations. The burial sites of this region show clear cultural similarities (e.g. high pedestalled bowls of the same shape and ornamentation), but also display strikingly distinctive local features. Thus, the wealth of gold offerings is without comparison at any other burial site of the early Iron Age period in this region and the great number of bronze drums from the site - although mostly undocumented - is hitherto unique for the southern parts of mainland Southeast Asia, far away from the Dong Son cultural area.

|

Gold jewelry from different Cambodian burials |

|

Jewelry found in the burial mound of the first “Golden Man” in 1970 |

The Bronze Age civilization that flourished on the Mediterranean island of Crete is known as the Minoan. Because Crete lay near the coasts of Asia, Africa, and the Greek continent and because it was the seat of prosperous ancient civilizations and a necessary point of passage along important sea-trading routes, the Minoan civilization developed a level of wealth which, beginning about 2000 bce, stimulated intense goldworking activities of high aesthetic value. From Crete this art spread out to the Cyclades, Peloponnesus, Mycenae, and other Greek island and mainland centres. Stimulated by Minoan influence, Mycenaean art flourished from the 16th to the 14th century. Middle Minoan period, in Greece, when rapid social changes took place, with palaces emerging for the first time, but also being destroyed and having to be rebuilt. The Minoan society was changing rapidly and the people associated with the palaces needed consensus from the larger population, to affirm their social ranking and maintain control.

The emerging social tensions increased the power of religion as a stabilizing force for maintaining the social structural of order. The recurring iconography of a Minoan goddess descending on a throne seems to became a key symbol of the legitimization of the new social order. In the Bronze Age, Mycenaean people had strong spiritual beliefs about an afterlife and the fact that we are seeing bodies that have been embalmed and items buried with them, gives evidence for this. They believed that once you die, your body needs to be respectably buried for it to be able to move on and that you also needed objects from the material world to take up with you in the after life. This was not only for use in the afterlife, but they thought that to get to the afterlife, you had to cross a river that charged a fare, so if you did not have items to pay, then you would not get to go to the next life. A profusion of gold jewelry was found in early Minoan burials at Mókhlos and three silver dagger blades in a communal tomb at Kumasa. Silver seals and ornaments of the same age are not uncommon.

|

Minoan Gold bracelet, the eyes and eyebrows were originally inlaid. |

The first evidence of jewelry making in Ancient Egypt dates back to the 4th millennia BC, to the Predynastic Period of along the Nile River Delta in 3100 BC, and the earlier Badarian culture (named after the El-Badari region near Asyut) which inhabited Upper Egypt between 4500 BC and 3200 BC. From 2950 BC to the end of Pharaonic Egypt at the close of the Greco-Roman Period in 395 AD, there were a total of thirty-one dynasties, spanning an incredible 3,345 years!

Figure on the left shows a pectoral that hangs from a single string of cylindrical beads of blue faience and gold, a rearing Uraeus guards, the Wadijet-eye and the hieroglyph Sa is placed beneath it on the inner side. Figure on the right shows a pectoral scarab that contains gold, silver, cornelian, lapis lazuli, calcite, obsidian and red, black, green, blue and white glass. The central necklace motifs consist of a bird with upward curving wings whose body and head have been replaced by a fine scarab. It represents the sun about to be reborn. Instead of a ball, the scarab is pushing about containing the scarab Wadijet-eye which is dominated by a darkened moon, holding the image of Tutankhamun become a god, guided and protected by Thoth and Horus. Heavy tassels of lotus and composite bud forms are the base of the pendant.

Wig of gold, onyx and stained glass. 1479-1425 BC. Used by one of the wives of Thutmose III

The earliest known record concerning the making of jewelry is found in Egypt. It is here along the stone walls of the chapel chambers of ancient tombs that the true history of jewelry begins. On these walls are reproductions of the Egyptian lapidary at work. This craftsman was essential to Egyptian jewelry for it was his job to cut and engrave the many small stones found in almost all Egyptian work. During this time, the jeweller was not only a skilled craftsman who made ornaments for personal adornment, but a goldsmith and engraver of metals for any purpose, including the minting of coins. Although the beginnings of jewelry as we know it can be traced to this time, Egyptians also had characteristic forms of jewelled ornaments for which we have no equivalent. The pectoral is one of these.Ancient Egyptians began making their jewelry during the Badari and Naqada eras from simple natural materials; for example, plant branches, shells, beads, solid stones or bones. These were arranged in threads of flax or cow hair. To give these stones some brilliance, Egyptians began painting them with glass substances. Since the era of the First Dynasty, ancient Egyptians were skilled in making jewelry from solid semiprecious stones and different metals such as gold and silver. The art of goldsmithing reached its peak in the Middle Kingdom, when Egyptians mastered the technical methods and accuracy in making pieces of jewelry. During the New Kingdom, goldsmithing flourished in an unprecedented way because of regular missions to the Eastern Desert and Nubia to extract metals. These substances were processed and inlaid with all sorts of semiprecious stones found in Egypt; for example, gold, turquoise, agate, and silver.

The ancient Egyptians placed great importance on the religious significance of certain sacred objects, which was heavily reflected in their jewelry motifs. Gem carvings known as “glyptic art” typically took the form of scarab beetles and other anthropomorphic religious symbols. The Egyptian lapidary would use emery fragments or flint to carve softer stones, while bow-driven rotary tools were used on harder gems.

|

Bracelet from the Oxus treasure, Achamenid period, British Museum. London. |

|

Gold necklace, with king and flanking lions in carved lapis lazuli; Sassanian period, 5th - 6th century A.D. |

|

| Elements from a necklace, probably 14th century Iran Gold sheet, chased and inset with turquoise, gray chalcedony, glass; large medallion |

|

A Parthian empire collar necklace from a tomb in Tillia Tepe, Afghanistan. 1st. century AD |

|

Parthian gold jewelry discovered in graves located at Nineveh in northern Iraq. The Persian Empire collection of the British Museum. |

|

| Scythian Emulate |

|

Bead necklace, Achaemenid period, c. 350 BC Acropolis, Susa, Paris, Louvre Museum |

|

Pendant representing a naked Goddess. Electrum, made by a Rhodian workshop, ca. 630-620 BC. Found in the necropolis of Kameiros (Rhodes). |

|

Pendant, Phoenicia 600BC-500BC, Gold set with green glass, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

Collar known as The Shannongrove Gorget, maker unknown, Ireland, late Bronze Age (probably 800-700 BC). Victoria & Albert Museum, London. |

|

Medallion with Eros, hair ornament, second half of the 3rd century BC, Hellenised Orient, Paris , Louvre Museum |

|

Kingston Down brooch, Anglo-Saxon, early seventh-century. The ‘step’ pattern recalls the centre of the St Mark carpet page in the Lindisfarne Gospels. |

|

Ancient Greek jewlry from Pontika (now Ukraina) 300 bC. It is formed in a Heracles knot. |

|

A gold bracelet, weighing over 1.3 pounds and found on a victim in Pompeii, was part of a traveling exhibit displayed at the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois in 2005 |

|

A pair of first century earrings, from a tomb in Tillia Tepe, Afghanistan, when they were on display at the 'Afghanistan, Rediscovered Treasures' exhibition at Muse Guimet in 2006 in Paris, France. |

|

Gold, set with table-cut emeralds, and hung with an emerald drop from Colombia, currently exhibited at Victoria and Albert Museum |

|

Gold and pearl earring found in the City of David archaeological excavation below the Old City walls in East Jerusalem, Israel, in November, 2008. |

|

Antique Nose Ring from India, with Gold, Pearls and Jadau work. 19th century. [courtesy Wovensouls collection] |

|

Andhra Pradesh Royal earrings 1st Century BCE |

|

A gold broach with turquoise and a pearl, from the first century, was discovered in 1978 on the archeological site of Tillia Tepe in northern Afghanistan. |

|

First-century earrings from a tomb in Tillia Tepe, Afghanistan. Thierry Ollivier/Muse Guimet/Getty Images |

|

Gold earring from Mycenae, Late Helladic I (16th century BC). |

|

Ancient Egyptian collar necklace |

|

Rosette, maker unknown, Tuscany, 530 BC. Victoria & Albert Museum, London. |

|

Pendant Unknown maker England 1540 - 1560 Enamelled gold, set with a hessonite garnet and a peridot, and hung with a sapphire Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

Ivy Wreath. Mid 4th century B.C., Dion Archaeological Museum |

|

Oak Wreath. Mid 4th century B.C., Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum |

|

Earrings decorated with a siren and sea shells , Late fifth century B.C., London, British Museum |

|

Gold snake Bracelet , Greek-Hellenistic Period, first half of the 2nd century B.C, Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

Necklace with Sapphire Pendant, bow about 1660, chain and pendant probably 18-1900. Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

Breast ornament About 1620 - 1630, France (possibly) Enamelled gold, set with 208 table-cut and triangular point-cut diamonds, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

Bodice Ornament, About 1680 - 1700, Holland (possibly), Rose-cut diamonds and hessonite garnets set in gold and silver, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

Enamelled gold pendant in the form of a three masted ship hung with pearls, Designed and made by Reinhold Vasters, Aachen, Germany About 1860, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

The Danish crown Christian IV's crown of gold, enamel, diamonds and pearls, created 1595-1596 by Dirich Fyring in Odense. |

|

Kiani Crown of Iran was made for the coronation of Fathali Shah of Ghadjar Dinasty in 1797. |

The Imperial Crown of Russia

Crafted by Cartier in 1921 - this tiara is to be worn on the forehead, parallel to the line of the brows. It has 577 brilliant and rose cut diamonds, designed for the Tysckiewisz family. The central stone was once a jonquil yellow diamond of over 71 carats. It was eventually replaced with this large star sapphire. As a bit of a surprise, the central element is mounted en tremblant so that it can move slightly when worn. ~ Attire's Mind

|

| Gold Greek and Etruscan hinged bangle, 1880 to 1885 , Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

| Silver gilt necklace by August Kiehnle, circa 1885, Archeological revival style from the 4th century B.C.- Greek , Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

| A Tiara in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A Tiara in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A Ruby Tiara in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| The Shield of Nadir Shah |

|

| A necklace in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A circa 1770 watch with works by Pierre Viala, Geneva , Pforzheim, Schmuckmuseum |

|

| A gem encrusted pitcher in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

|

| A gem encrusted dish cover in the Iranian Crown Jewels |

The Empress Josephine tiara, created in ca.1890.

This exceptional jewel is referred to as 'The Empress Josephine Tiara' on account of the fact that the briolette-cut diamonds in the tiara were a gift from Tsar Alexander I of Russia to the Empress Josephine. The Tsar used to bring presents for Josephine when he visited her at La Malmaison, following her divorce from Napoleon.

This was one of the rare tiaras made by Fabergé jewelry house, crafted by their Finnish master jeweler August Holmström.

After the Russian Revolution the Leuchtenberg family sold the tiara and it was bought by the Belgium royals after World War I. When Queen Elisabeth of Belgium passed away her son Prince Charles Theodore inherited it in 1965. The tiara then passed nto Queen Maria Jose’s hands when Charles Theodore passed away in 1983. Princess Maria Gabriella inherited the tiara in 2001 and later put the tiara up for auction in 2007.

In 2007 it went up for auction at Christie's in London, fetching over £1 million and was bought by Fabergé super-collectors, the McFerrin family, and is on permanent loan to the museum along with 600 other Fabergé treasures.

Art Nouveau, and Jugendstil Jewelry

|

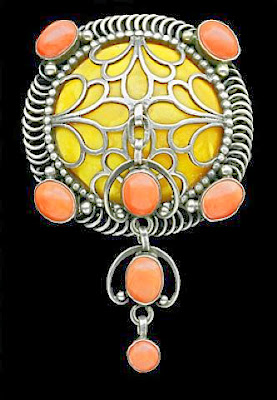

| Pendant-brooch, designed by C.R. Ashbee and made by the Guild of Handicraft, about 1900, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

Contemporary jewelry style has appeared in the 1930s , influenced by various artistic movements including Art Nouveau, cubism, minimalism, dadaism, pop arts and so on. The pieces of this genre moved from personal adornment to wearable art due in part to the advent of new materials that were created and manufactured around the same time including various synthetic materials and artificial gemstones. Moreover, other metals were used instead of the traditional gold and silver, such as stainless steel and copper, to make pieces more affordable as well as interesting.

|

| French 2nd Empire, Serpent Bangle Gold Enamel Ruby Diamond, c.1865 |

|

| Charles Boutet de Monvel (1855-1913),Peacock Pendant, Gilded silver Plique-à-jour Ruby Emerald Pearl, French, c.1904 |

|

| Jugendstil Buckle Silver Enamel Chalcedony, Max Joseph Gradl (1873-1934) for Theodor Fahrner, German, c.1900 |

|

| Meyle & Mayer (Pforzheim) Jugendstil Floral Locket Silver Enamel Mirror Pendant, Dragonfly German, c.1900 |

|

| Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942) - Guild of Handicraft, Brooch/Pendant, c. 1900 - Enamel on copper and silver with cabochon amethyst \ JV |

|

| Art Nouveau Aqua-Organic Brooch European. Circa 1900 Gold n |

|

| Art Nouveau Gold, Sapphire, and Plique-a-Jour Enamel Pendant, Marcus & Co. |

|

| Dorrie Nossiter (1893-1977). Arts & Crafts Pendant Necklace Gold Silver Jade Sapphire Tourmaline Pearl. British, c.1925 |

|

| Ludwig Knupfer for Theodor Fharner, Jugendstil Brooch Silver Enamel Chalcedony |

|

| Arts & Crafts silver necklace set with moonstones. English. Circa 1900. Central panel Frances Thalia How exhibited 1896-1928 & Jean Milne exhibited 1904-1917. |

|

| A domed silver Arts & Crafts brooch decorated with very fine wirework and gold bobbles set with a citrine and three mother- of- pearl plaques. British. Circa 1900. |

|

| A silver pendant of entwined, enamelled serpents surrounding a sapphire, the pendant with pearl drops. Scottish. Circa 1900. Unmarked |

|

| An Arts & Crafts, silver pendant set with a central red enamel plaque which is overlaid with flowering rose branches. Original chain and clasp. English. Circa 1910. |

|

| An Arts & Crafts, silver pendant set with carnelian stones. Original chain and clasp. English. Circa 1910. |

|

| Jugendstil Baltic Pendant, Silver Amber, Polish, c.1910 |

|

| Heinrich Levinger , Jugendstil Stylised Tree Pendant Possibly designed by Otto Prutscher, Silver Enamel Pearl-- Schmuck in Deutschland und Osterreich 1895-1914, Ulrike von Hase, 1977, p.328-329 |

|

| Buckle and belt tag, Henry Wilson About 1905, London Silver, cast, chased, enamelled and mounted with cabochon-cut stones. Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

| Brooch, Charles Desrosiers, Paris. 1901, Gold and enamel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

| Pendant, Archibald Knox, About 1900, Birmingham, Enamelled gold, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

|

| Archibald Knox |

|

| Archibald Knox Brooch for Liberty |

|

| Archibald Knox Brooch for Liberty |

|

| Necklace, Designed by Alfredo Castellani (1853 - 1930), Rome, Italy, 1925. Gold mounted with 21 scarabs of cornelian, Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

|

| Brooch, Possibly Van Cleef & Arpels, Paris, About 1930, Platinum and gold set with baguette- and brilliant-cut yellow diamonds, emeralds, sapphires and rubies, Victoria Albert Museum, London |

|

| Levinger & Bissinger Plaque-de-cou |

| Jean Auguste Dampt Stick Pin |

|

| Felix Rasumny Art Nouveau Brooc |

|

| Maurice Daurat Grasshopper Pendant |

|

| Auguste Gross, Art Nouveau Brooch |

|

| Joë Descomps Pendant / Brooch |

|

| René Beauclair, Fuchsia Brooch |

|

| Charles Boutet de Monvel Pendant |

|

| Henri Vever Cloak Clasp |

|

| Edouard -Aime Arnould Buckle |

|

| Rene Lalique Ring |

|

| Georges le Turcq Ring |

|

| Ferdinand Zerrenner Attrib. |

|

| Max J. Gradl Buckle for Fahrner |

|

| Wiener Werkstatte Brooch |

|

| Meyle & Mayer, Art Nouveau Locket |

|

| Georg Kleemann, Brooch for Fahrner |

|

| Georg Anton Scheid Brooch |

|

| Bernard Hertz Skonvirke Brooch |

|

| Murrle Bennett & Co Brooch |

|

| Gold, peridot and emerald brooch, David Webb |

|

| White enamel and diamond crab long chain, David Webb |

|

| Green fish, Gold, enamel, cultured pearl, ruby and diamond brooch , David Webb |

|

| White snake, enamel, ruby and diamond brooch, David Webb |

|

| White cow, enamel, emerald and diamond brooch, David Webb |

No comments:

Post a Comment