|

| Elizabeth Bowen |

Elizabeth Bowen

THE HEAT OF THE DAY

A revised version of this article appears in the book London Fictions, edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White - and published by Five Leaves in April 2013.

Jane Miller

April 2013

The Heat of the Day is famous for being Elizabeth Bowen’s London wartime novel, though she wrote other novels set in London, and several of her best short stories deal, sometimes as ghost stories, with the strange hiatus amid the continuities which characterised London life during and just after the Blitz. There was very little about her times, or the places her characters inhabit, that Elizabeth Bowen took for granted or assumed her readers would know already, and in this novel London is minutely scrutinised and accounted for from the first Sunday of September 1942 to the same Sunday two years later. More than that, though. Place and time are palpable forces in a novel which traffics in rain and sunlight, in the ‘tired physical smell’ of London, in the total darkness of the Blackout and in the vivid contrasts between night-time bombing and the light-hearted relief people felt during daylight hours, as the substance and temper of its characters’ emotional life. Anxiety, suspicion, fear envelop the lovers at the centre of the novel, who are curiously sketchy, despite their moments in bed and their elegant dressing-gowns. Yet they are also believably happy together, in love as neither has ever been before and unexpectedly at ease with one another. So that London is for both of them a place of nightmare, darkness and danger, but also the dodgy home and encourager of love. Bowen apparently found this the most difficult of all her novels to write. She started it as the bombs were still falling in 1944, and it was not published until 1949. The novel is, in some ways, a casualty of war itself, damaged in certain places, the prose often fractured and eliptical, with verbs and articles left out, and odd breaches of idiom: contortions which catch the contortions of the time. It is also capable of inducing precisely the excitement and the anxiety lurking at its heart.

|

| Charles Ritchie, 1957 |

Stella and Robert, the novel’s lovers, are ‘creatures of history, whose coming together was of a nature possible in no other day.’ This is not so much a grand claim for the peculiarity of their situation as a simple truth about how things were in London during the Second World War: ‘War time, with its makeshifts, shelvings, deferrings, could not have been kinder to romantic love.’ Elizabeth Bowen herself had a passionate affair through most of the war with a young Canadian diplomat called Charles Ritchie, to whom she dedicated the novel. Social and family life became difficult for all Londoners. For the middle classes there was not only food rationing but very few servants. It was sometimes possible to be private, though, anonymously and anomalously housed, and, at the same time, to communicate outside with people you’d never have known in normal life.

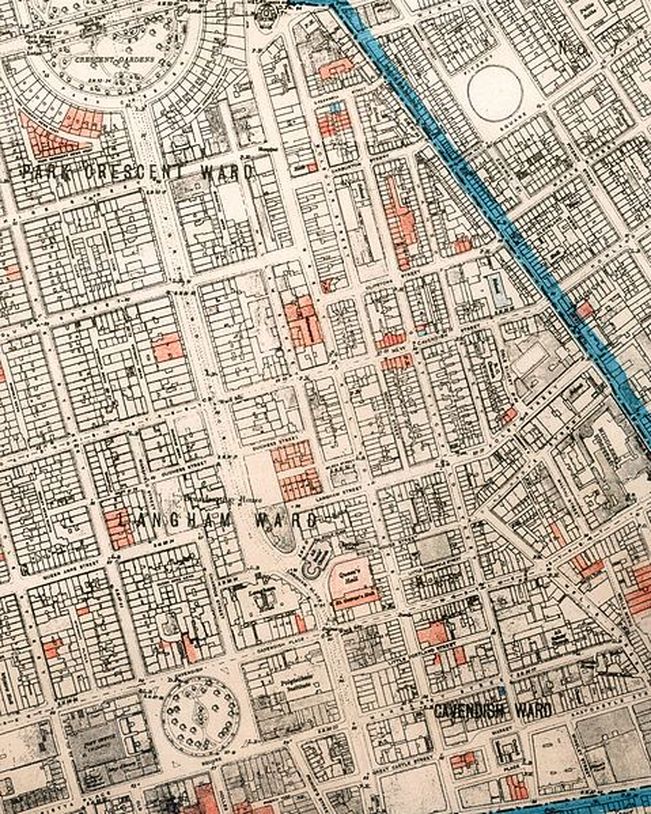

Within its two-year span, the novel shifts nervously back and forth in time, making little forays out of the city as if to escape the bombing, always uncertain of the events it narrates and of their sequence, and returning from its excursions, it can seem, on the orders of some badgering inquisitor, determined to achieve at least a glimmer of clarity, an explanation in the face of all this. ‘Ghostly’ is a word that crops up a good deal, and ‘haunting’. Many of her wartime stories, ‘In the Square’, ‘The Demon Lover’ and ‘Mysterious Kôr’, for instance, focus on the phantasmogorical effect on people of living amongst bombed houses and an only partly recognisable landscape. The Heat of the Day starts in Regent’s Park, autumnal, slightly fly-blown, with its bandstand still just bandstanding to an assortment of mostly lonely derelict people. A plump, ungainly young woman, working-class and speaking a form of English derived, it sometimes seems, from a rare variant of dyslexia, makes an awkward friendly pass at her neighbour, who, shifty and unkind, testily puts her down. It is a London of solitary strangers and drifting leaves, a ‘tarnished’ version of the Regent’s Park that glitters in winter sunshine at the beginning of Bowen’s earlier, pre-war novel, also set in London, The Death of the Heart. This, we quickly realise, is to be a London transformed by the war.

|

| Weymouth Street, W1 |

Stella has lived stylishly on the edge of Regent’s Park in a Nash terrace house of exactly the kind that figures in the earlier novel and which Bowen herself inhabited until she was bombed out in 1944. Stella’s house has been bombed too, just as Bowen’s was, so that we meet her first in the elegant, characterless flat she has rented at the top of a high house that empties itself of its doctors at night and at weekends, near to the park and the shell of her old house. Weymouth Street must have possessed the heavy impersonal grandeur in those days that it still does. Stella works all day in a secret branch of government (as Bowen herself did) and here she is on that Sunday evening, in the middle of a querulous conversation with the man we’ve already met in the park earlier in the day, as he snubbed the young woman who’d hoped to go home with him. He is the one being snubbed now, by this attractive fortyish woman to whom he appears to be offering himself, having surprisingly invaded the bleak refuge her flat provides. He is offering himself, it turns out, in exchange for the information that Stella’s lover Robert (who is also engaged in secret government work) is selling secrets to the enemy, a fact he is prepared to withhold, or which he might, at least, delay in divulging - in the interest of catching bigger fry - if she accepts him as her lover.

Harrison, as his name turns out to be, is an alarming presence, insistently and disagreeably material, yet ghostly in his comings and goings, so that neither Stella nor the reader can be sure whether he is telling the truth about her lover, let alone about his own role and his ability to intervene as he is proposing to do. The scene gives us our first taste of the novel’s jumpiness and terror and of its central theme: love is no guarantee of truth or trust and provides no protection against betrayal. Is it, indeed, ever possible to know whether someone is telling the truth? Harrison, it turns out, is called Robert too. How is Stella to adjudicate between these two Roberts, or, perhaps, even distinguish between them?

She keeps quiet about Harrison’s accusation for two months, and the reader is no clearer than she is about whether her lover really is a spy. Her anxiety permeates the novel as we watch her getting on with her life and trying to ignore Harrison’s blandishments. We return to the young woman in the park, Louie, and her cannier friend, Connie, and listen, somewhat disbelievingly, perhaps, to their chatter. Connie is a reader of newspapers and is clear about the progress of the war. She has reminded Louie, as Louie later remembers, of ‘the advantage I should be at if I could speak grammar’. Louie’s husband, Tom, is a soldier in India, and her parents have been killed by a direct hit on their house. She is not a Londoner, and her sturdy, optimistic nature is out of its element in this injured and complicated city. From loneliness and an apparently innocent desire for company of any sort, Louie occasionally approaches men and takes them home with her. She failed with Harrison, as we’ve seen.

There are glimpses into Stella’s life. We are told that she left her husband, and needn’t have bothered to divorce him, as he died just afterwards. She has a twenty-year-old son, Roderick, one of Bowen’s oddly affectless young men, who spent a futile year at Oxford before being called up. She visits the estate in Ireland he is due to inherit from a cousin of his father’s, and Roderick later visits this cousin’s wife, who lives in an old people’s home. It is this old woman, who may be mad and is certainly unreliable, who reveals to Roderick that Stella was left by her husband for a ‘common’ nurse he loved and wanted to marry. Stella has misled the world and her son by preferring it to be thought she had callously left her husband, when the truth was that he rejected her as a very young mother for someone else. Her son feels betrayed by this untruth, with its curious mixture of innocence and self-serving denial, which prefigures Robert’s possible treachery and Stella’s possible reaction to it.

An unsettling visit to Robert’s mother and sister in the Home Counties offers some insight into Robert’s life. They live in an elaborately horrible house, ugly, demanding and impersonal, perpetually up for sale, and the uncomfortable setting for a family controlled by women and destructively dismissive of men and of sex. Robert’s father appears to have died defeated by all this, and ‘unstated indignities suffered by the father remained burned deeply into the son’s mind’. The bond between Stella and Robert draws on their shared experience of growing up unloved and knowing at first as well as second-hand what it is to be found wanting sexually.

|

| London during the wartime blitz |

When Elizabeth Bowen’s novels were reissued as paperbacks in 1999 to celebrate the centenary of her birth, the rereadings they occasioned were mostly serious and admiring; the savaging she had received earlier from critics like Elizabeth Hardwick, Raymond Williams and Angus Wilson, amongst others, refuted or forgotten. She was not, and would not have wanted to be, received into the feminist literary fold, though she sometimes figured on lists of women writers denied their due. The charges against her were of snobbery, of having ‘the moral intransigence of the interior decorator’ (Hardwick), of ‘special pleading’, so that ‘the reality of society is excluded’ (Williams), and of inhabiting ‘the land of the middlebrow’ (Wilson). These charges seemed to many of her readers unfair and malicious, and to some extent familiar and typical of how serious novels written by women were often read. It is certainly true that Bowen wrote mostly about middle and upper-class people, that she was perhaps over-exercised by the differences among members of those groups and often clumsy in her treatment of working-class characters. But there was also something direct and honest about her sense of class, so that, for instance, Stella at one point wonders whether her class is perhaps the only thing she has going for her; and when Louie and she are brought together by Harrison, both women are immediately and self-consciously aware of the class differences manifested in their clothes, their speech and their demeanour. Stella notices Louie’s crooked seams and ‘flimsy gloves’, while Louie goes home to ponder the meaning of the word ‘refined’. Each woman is intrigued by the other, however, and not in the least repelled.

Bowen’s novels are full of servants and other working-class characters, and they are by no means all walk-on parts, though they are sometimes possessors of peculiar speech habits. They often stand in the novels for energy, straightforwardness and a capacity for warmth and feeling that Bowen clearly admired. In Death of the Heart, for instance, the seaside household of the Heccomb family is portrayed as lively, humorous and good at enjoying themselves, in absolute contrast to the repressed and mannered tastefulness of the Quayne family in Regent’s Park. While Portia, the unhappy orphan at the centre of the novel, relies on the kindness of the housekeeper in a house where she is continually let down by her adoptive family and their friends. The two young working-class women in The Heat of the Day are affectionally drawn, and the birth of Louie’s illegitimate baby at the end of the novel is a positive, life-affirming moment, strikingly at odds with references throughout the novel to false or phantom pregnancies, which yield questions and secrets rather than living infants.

Bowen, it seems - or at least it is rumoured - was briefly a member of the British Communist Party, like many of her friends and fellow writers, and though this by no means guaranteed sympathy with or knowledge about working-class people, let alone identification with their far greater vulnerability in wartime London, it is not without significance. Bowen was an only child. Her father suffered for many years from a serious breakdown, so that her mother took Elizabeth to England, where she died when her daughter was only thirteen. Thereafter, her life was spent in boarding schools and with an aunt, though she did live with her father in Ireland during the holidays. All this certainly introduced her to one version of social exile, a particular form of rootlessness and homelessness, which is like the experience of many of her heroines. She was also, it has to be said, seduced by grand old houses, and the Irish one in this novel, which Stella’s son inherits, is clearly based on Bowen’s Court, which the author inherited from her father.

The Heat of the Day is also remembered as a novel about spying. It is sometimes compared with Graham Greene’s The Ministry of Fear and not always to Bowen’s advantage. Readers have wondered why Robert spies for the Nazis rather than the Russians, though it is likely that spying for the Russians would have carried too many distracting ambiguities in 1942. Nor do we know what kinds of secrets he was handing over or to whom. Are we to assume that Robert seriously impedes the war effort and may even have caused the death of friends and colleagues? Bowen wilfully denies us satisfaction on these points and concentrates instead on the dilemma Robert poses for Stella. When she does finally confront him with Harrison’s accusation and her own two-month delay in telling him about it, his first instinct is to lie, and he does this convincingly for a moment, and then blusteringly proposes marriage. Stella only knows for certain that he has been spying when Harrison is able to pinpoint the exact moment when she asked Robert if he was a spy: a moment that was followed, just as Harrison had predicted it would be, by instant moves to cover his tracks.

Stella finds herself telling Harrison about the lie she’s told about her marriage. They have dinner together in a basement bar off Regent’s Street, where lights blaze in frantic denial of the darkness outside, and she formally offers herself to him in a last-ditch attempt to deflect him from Robert, only to be turned down by him, as he had been by her. Robert, meanwhile, has mysteriously made off to his mother’s hated house, the scene of his father’s humiliations, which is suddenly coveted by a real-life buyer: presumably someone in pursuit of Robert, almost certainly Harrison. Robert returns to London and the final reckoning. Stella and he are in bed together for what they know to be the last time when he delivers a mystifying diatribe as explanation of his spying. He is, above all, contemptuous of the language of loyalty, he tells her. Words like ‘betrayal’ and ‘freedom’ are part of the ‘racket’, a ‘dead currency’ he has learned to immunize himself against. He has longed for ‘scale’, ‘vision’, grandeur. Wouldn’t she wish that for him too, even expect it of him? Stella is astonished, as the reader is, by his chaotic, vaporous words,

Freedom, Freedom to be what? - the muddled, mediocre, damned. Good enough to die for, freedom, for the good reason that it’s the very thing which has made it impossible to live, so there’s no alternative. Look at your free people – mice let loose in the middle of the Sahara.

It is possible that Robert’s wasted anger, his ranting and generalised ‘disaffection’, as he calls it, echoes some of the sentiments Bowen harvested while she was in Ireland during the Second World War, when she was required to report on the character of Irish neutrality. Roy Foster, in his Modern Ireland 1600-1972, quotes from one of her reports,

The most disagreeable aspect of this official ‘spirituality’ is its smugness, even phariseeism. I have heard it said (and have heard it constantly being said) that ‘the bombing is a punishment on England for her materialism.’…And there is still admiration for Franco’s Spain…The effect of religious opinion in this country (Protestant as well as Catholic) still seems to be, a heavy trend to the Right.

Robert’s disgust with the war seems less principled and even more negative than the testimony of Bowen’s Irish men and women, though it is possible that Bowen found his not invoking religious or spiritual reasons for the position he has taken up preferable to the Irish versions of it she had listened to. It is also clear that many people Bowen knew (including her lover, Charles Ritchie) felt no enthusiasm for the war, though they may not have expressed this quite as Robert does. His explanation appears arrogant as well as smug, and it is delivered in the voice of an officer and gentleman used to getting his way.

This war’s just so much bloody quibbling about some thing that’s predecided itself. Either side’s winning would stop the war; only their side’s winning would stop the quibbling. I want the cackle cut.

We are left to attribute his behaviour principally - as Stella does - to what he thinks of as his father’s weakness and humiliations. His work for the enemy, he tells her, ‘bred my father out of me, gave me a new heredity.’ We cannot know for certain whether his subsequent fall from her roof to his death is an act of suicide or murder, or an accident, nor whether it is to be considered brave, foolhardy or expedient. Stella firmly protects his name and his purpose as she gives evidence at the inquest on his death, and she is regarded as ‘a good witness’.

When a telegram arrives announcing the death of Louie’s husband, Tom, at the very moment that Connie is writing a letter to explain Louie’s pregnancy to him, Bowen declares that ‘questions to which we find no answers find their own.’ She depicts a world in which lying is ubiquitous and probably unavoidable. She believed, to some degree, in coincidence and in ghosts and haunting, and even more so in the unknown and the unknowable. She may also have believed in doubles. She expected us to make do with what we were given, and to see uncertainty as intrinsic to fiction as it is to life. And it is true that these mysteries are not disappointing. Towards the end of the novel Stella is sitting in a train going out of London and looking into the rooms and houses she passes,

Sometimes Stella was fortunate in being able to see through railings or over fences not only yards and gardens but right into back windows of homes. Prominent sculleries with bent-forward heads of women back at the sink again after Sunday dinner, and recessive living-rooms in which the breadwinner armchair-slumbered, legs out, hands across the eyes, displayed themselves; upstairs, at looking-glasses in windows, girls got themselves ready to go out with boys. One old unneeded woman, relegated all day to where she slept and would die, prised apart lace curtains to take a look at the train, as though calculating whether it might not be possible to escape this time.

Stella’s watching eye, dispassionate, imaginative, yet restrained in its claims to know the whole story, is a reflection of what Bowen could do as a novelist. She could tell you how things looked and how they seemed and also how it might be possible to extrapolate from that to how people thought and felt. But you could never really know another person, and though love mattered more than anything it didn’t help. Bowen’s refusal to clear up confusions works especially well in this novel, where London’s inhabitants are watched groping for order and understanding in darkness and rubble and dust, and contending, often blithely, with shattering changes to their expectations and habits. Stella’s disappointment is that Robert did not share, as she’d thought he had, her sense of there being a peculiar romance to wartime London. She loves the place and the time they’ve occupied together, with its dangers and horrors and possibilities. Their love affair, passionately sealed off from their earlier lives within the alien enclosure of Stella’s rented flat, seemed to protect them from the dangerous world outside, as it pressed clamorously on walls and windows, with thick sooty smells and blinded nights. But she had also believed that it linked them to the destinies of other people in the world outside. So altered were everybody’s lives by what was happening that they could feel as if they were all ‘inside the pages of a book’, or indeed a ‘garrison’, in which unusual pleasures and company were to be sought and found in compensation for the wreckage outside. Robert has undermined that vision.

Bowen evokes the tangled physical reality of the time, its extremes and opposites, in an awkward, broken language,

Out of mists of morning charred by the smoke from ruins each day rose to a height of unmisty glitter; between the last of sunset and first note of the siren the darkening glassy tenseness of evening was drawn fine. From the moment of waking you tasted the sweet autumn not less because of an acridity on the tongue and nostrils; and as the singed dust settled and smoke diluted you felt more and more called upon to observe the daytime as a pure and curious holiday from fear.

Stella is haunted by the intense beauty of daybreak and the horrors it can manage to disguise:

Most of all the dead, from mortuaries, from under cataracts of rubble, made their anonymous presence – not as today’s dead but as yesterday’s living – felt through London.

The novel ends on an ambiguous note of renewal. Stella tells Harrison that she is going to marry a distant cousin, a Brigadier, who has kindly ignored her shaky past and unusual connections; and Louie’s baby, Tom, is growing to look more and more like the man who was not his father. It is not a return to normality or peace, but some careful human adjustments and accommodations are being made to this extraordinary time.

Jane Miller is Professor Emeritus, London University Institute of Education and the author of, among other titles, Women Writing about Men, Many Voices and Relations.

No comments:

Post a Comment