It’s been short, long, straight and punky – reflecting the twists and turns of my life and my homeland, Cameroon

The 10 Best Books of 2021

Imbolo Mbue

Saturday 4 February 2017

In the summer of 2002, I walked into a hair salon in New Jersey and asked a stylist to cut off all my hair. I was done having hair. Enough with the pain of straightening it with a chemical that scalded parts of my scalp and left others in blisters. Enough with the discomfort of braiding it – eight hours of tugging and wincing followed by painkillers to ease the soreness, or a full day of not being able fully to turn my head.

Free me from this burden, I told the stylist, who stared at me, confused, while I ranted. She tried to convince me merely to trim it, but I told her I wanted it all gone. Reluctantly, she obliged and I walked out that afternoon to the sensation of the wind on my bare scalp. The feeling was ineffable, my newfound freedom unquantifiable.

I regrew my hair into a short afro and cut it all off again before it reached the length where its coarseness made combing a battle. I did this several times, until I decided to stop with the cutting. Why was I running away from my hair’s texture, I asked myself: wouldn’t it be better – and healthier – to embrace it? It certainly wouldn’t be easier, I knew that, but I decided to experiment nonetheless, determined to confront every knot and tangle and find the beauty therein.

Last November, while detangling (a process that takes at least an hour and requires a lot of oil and patience), I received a phone call from a friend. There was an uprising in Cameroon, she said. Hundreds of our fellow anglophone Cameroonians were rioting and protesting. The government had unleashed its soldiers. Some protesters had been arrested. A few might be dead. Our struggle – “the anglophone problem” – was back in the spotlight. I sighed, too disturbed to respond. Hadn’t we had enough?

I was perhaps seven years old when I realised I was anglophone, and therefore a member of my country’s linguistic minority. Television had just arrived in Cameroon, and most of the programmes on our sole TV channel were in French. Not that I minded: it was the 80s and, like most children in our village, I was simply happy to have a screen to stare at. There were music videos from all over Africa, and white people kissing and laughing in places we knew little about. For adults who wanted to know what was happening beyond the village, the nightly news was broadcast in English, right after the French version. Scarcely knowledgeable about the outside world, I thought much of the globe was made up of bilingual countries. It was only when I was a preteen, living in my hometown of Limbe, that I began to comprehend the challenges of being English-speaking in a predominantly French-speaking country.

How did our country come to be so divided? Colonialism: how else? The Portuguese “discovered” us, but didn’t stay long. The Germans came next, ruling for decades. After the first world war, we became the property of France and Britain, and France took the bulk. French Cameroon gained independence in 1960, and the following year, the British-ruled part chose to reunite with it. Our nation was reborn as two fully autonomous states, and the constitution included clauses to ensure that the bigger, French-speaking partner did not overwhelm its smaller companion.

But overwhelm it did. Under the guise of “national unity”, Cameroon’s francophone president sponsored a referendum in 1972, and it became an autocratic, one-party state. Cameroon is now divided into 10 regions: eight francophone and two anglophone, with anglophones comprising roughly 17% of the population.

By the time I started secondary school in 1991, this minority was deep in post-reunification regret. Despite the government’s rhetoric about equality, it was clear to me, even as a child, that power emanated from the French-speaking regions. Virtually every high-ranking government official was francophone. The government-owned oil refinery in Limbe was run largely by francophones; few people from my community could get jobs there. Our president, Paul Biya, in power since 1982, is a francophone. His cabinet was made up almost exclusively of francophones.

Throughout my preteen years, I heard stories of the disadvantages my older relatives and neighbours had faced. Students who attended the country’s sole university, in the francophone capital of Yaoundé, returned home with reports of how they were ashamed to speak English on campus, ridiculed for their attempts at French, and derogatorily referred to as “anglo-fou”.

But these disadvantages had little impact on my daily life. I walked with friends to school in the morning, and in the evening we played sizo (rope-jumping) and dodging (a game like dodgeball).

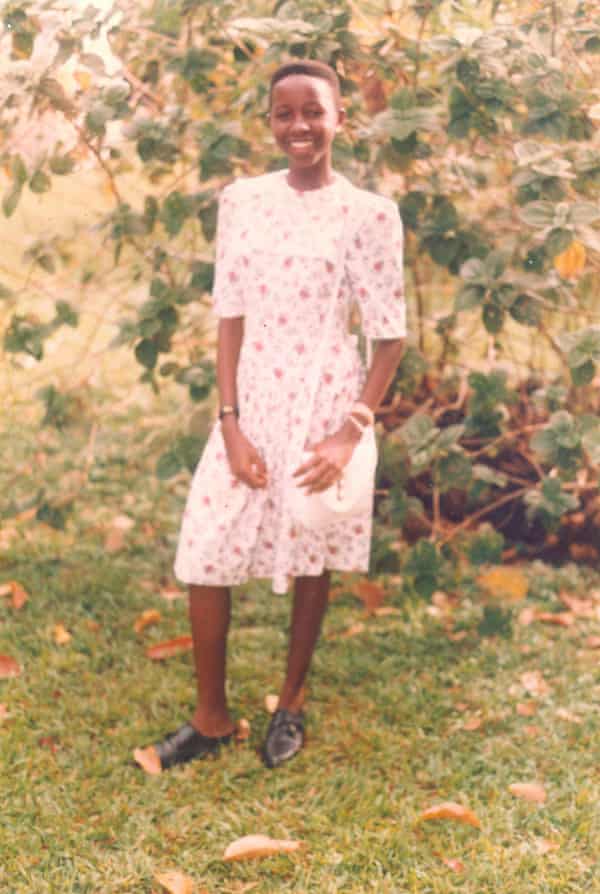

School pupils in anglophone Cameroon were forbidden from having long hair, unlike in francophone Cameroon, where the rules were much looser; so my friends and I made frequent visits to neighbourhood barbers, or asked family members to clip off our hair with scissors. Some of us sported a “rond-touche” (evenly cut head of hair), while others, myself included, had what we called a “punk”, our name for a high‑top fade – the higher the top, the more stylish. Once, I asked the barber to put two lines on each side, à la MC Hammer, for added flair. I loved my “punks” and how easy they were to comb. Francophone children had long hair, francophone adults ruled the country – but I couldn’t be more pleased to be an anglophone.

Anglophone adults, however, were growing increasingly unhappy with their second-class citizenship. When I was 11, an anglophone named Ni John Fru Ndi ran for president in Cameroon’s first multi-party elections, losing to Biya. Believing the election had been stolen – several third-party observers supported their claim – Ndi’s supporters rioted across the country the day the results were announced.

I remember running home from school that day with a cousin, passing through our town’s deserted open-air market where stalls had been turned upside down, baskets of green vegetables and smoked fish scattered all over by traders who had been forced to flee gunfire and teargas. I hid in my cousin’s house until the evening, when the rioting ceased and it was safe to go home.

Hundreds were beaten, imprisoned and killed for daring to protest, but Ndi and his followers did not relent. Though his party’s initials, SDF, stood for the Social Democratic Front, the hopeful among us decided that it stood for “suffer don finish”: pidgin English for “suffering is over”. That phrase soon became part of our local parlance, and we made up songs about it. “Oh my brothers, suffer don finish, oh,” we sang, “suffer don finish.” But no matter how often we sang, the end of suffering appeared nowhere in sight, even as we heard new reports of the arrest or imprisonment of protesters, opposition figures or journalists whose writings were deemed too subversive. That year, I learned a significant lesson: standing up against a government was a dangerous thing.

It was in this political climate that an anglophone secessionist movement arose, calling for the creation of a new country – Southern Cameroon. Could it really happen, I asked a teacher. Never, she replied: the government’s plan was to keep Cameroon united for ever. By the late 90s, the secessionist movement had mostly fizzled out. Around then, I finished high school and, thanks to the generosity of relatives, left Limbe to attend college in America.

I arrived in the States with my hair mid-length and straight because, well, I was on the verge of becoming an adult, and at home adult women grew their hair and chemically straightened it. After so many years of having a “punk,” it was good to graduate.

Many things about America fascinated me: burgers, department stores, the plethora of products designed to keep my hair straight. The first time I sat down to watch TV in my relatives’ apartment, I was struck that every show on every channel was in English: America was anglophone, like me. Eventually, of course, I realised I’d exchanged one minority status for another (racial), and the ordeals were strangely familiar.

My friends at college also had straight hair. If I didn’t go to the local African salon to get my hair braided, one of them straightened it for me in my dorm, my scalp scalding almost every time. Beautiful hair came at a price, but I figured a scalp dotted with blisters was mine: c’est la vie.

After college, unable to find a well-paid job, I wondered if I would be better off returning home. Family and friends reminded me that, because I spoke little French, I would have difficulty. So I decided to move to New York for graduate school, a big financial challenge. Not long after, I entered what I call my hair wilderness years.

I cut it to a short afro, coloured it, grew it, cut it and, years later, started braiding and chemically straightening it again, despite the inevitable scalding. I wished I didn’t have the thick, tangle-prone hair that shrunk upon contact with water; but I loved how it meant so little to me that I could cut it off or change its colour, and not feel I’d lost anything of worth. When I realised this indifference was in fact deep-seated negativity, I went to a men’s barbershop. Just as I had done 10 years earlier, I asked for them to buzz it all off.

Four years later, my hair journey continues, as does anglophone Cameroon’s journey to lasting equality. Our lawyers, students and teachers began protesting for constitutional rights. at the end of 2016. Online, I watch videos of soldiers beating peaceful protestors. On 21 November last year, in the Anglophone city of Bamenda, someone was killed; on 8 December, four more. More than 100 protesters were reportedly arrested and taken to Yaoundé; rumours are circulating that they will be tried for terrorism and could face the death penalty if found guilty.

The government denies the existence of an anglophone problem, only “a group of manipulated and exploited extremist rioters”. Students in the anglophone region have not yet returned to school, because teachers remain on strike. Soldiers are patrolling the streets. Most offices and businesses remain closed, and civil servants have declared that they won’t be returning to work until the government agrees to a dialogue. The government has shut down internet access across the anglophone regions.

Despite all this, Cameroon remains home, tangled and twisted as it might be. Even those of us who left it in search of a better life cannot wait to visit, because home is home. And our home is a beautiful one, with emerald hills and black sand beaches; dense rainforests and regal waterfalls. Our makossa music can keep you dancing all night, and our soccer team, though pitiful these days, once made history at the 1990 World Cup.

Our country so often makes no sense to us, but every chance we get, we cannot resist chanting, “Cameroon oh yay! Cameroon oh yay!” If we protest and risk death or imprisonment, it is because we believe our country has the potential to become “the land of promise, land of glory” we sing about in our national anthem.

My afro is now bigger than it’s ever been. I keep growing it, despite the fact that, with every added inch, the challenge of managing it multiplies. Ours is an idiosyncratic love affair, one I celebrate alongside my numerous identities which include: black, woman, immigrant, Cameroonian, anglophone, African, American, human. Perhaps I’ll cut off my hair again one of these days (to try a new style, or just because I feel like it). But, for now, just like my beloved homeland, it reminds me that, within a tangled, twisted, knotty situation, beauty resides.

No comments:

Post a Comment