Watership Down author Richard Adams: I just can’t do humans

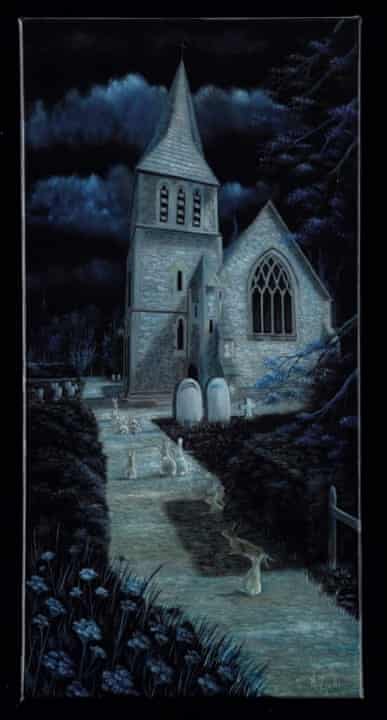

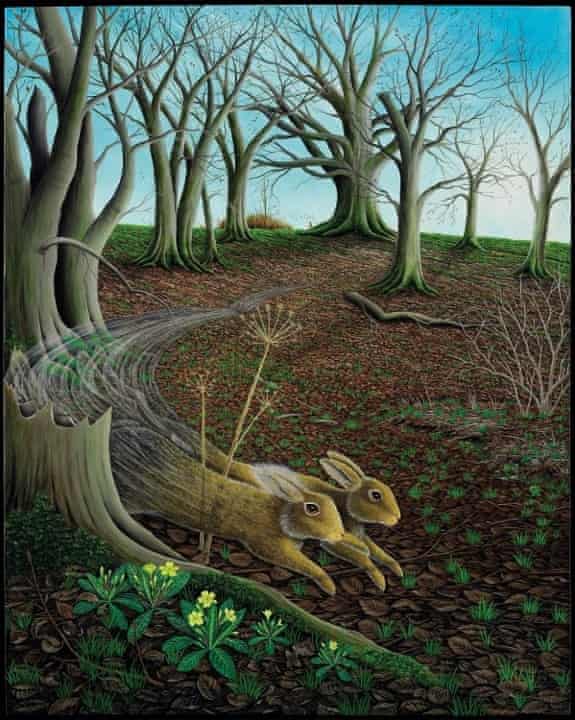

Watership Down, a story Richard Adams made up to scare his kids in the car, was rejected seven times before it became a classic. As a new illustrated edition is published, the author tells Alison Flood why he loves making children wince and weep

R

|

| Bedtime chiller … Richard Adams, now 94, at home in Hampshire. Photograph: Graham Turner/Guardian |

Adams, 94, is ensconced in an armchair in front of the fire in his 18th-century home in Whitchurch, Hampshire, where he and his wife Elizabeth have lived for the last 30 years. Appropriately enough, there are a few small rabbit statues under one of the tables. Next door, in a vast and higgledy-piggedly library, books are stacked to the ceiling. Elizabeth is watching him chat from the sofa, as is Ros, one of his daughters. “Yes,” says Ros, “he told us scary stories. And I wasn’t able to sleep.”

Watership Down was one of the first of these stories. Adams was 52 and working for the civil service when his daughters began pleading with him to tell them a story on the drive to school. “I had been put on the spot and I started off, ‘Once there were two rabbits called Hazel and Fiver.’ And I just took it on from there.” Extraordinarily, he had never written a word of fiction before, but once he’d seen the story through to the end, his daughters said it was “too good to waste, Daddy, you ought to write that down”.

He began writing in the evenings, and the result, an exquisitely written story about a group of young rabbits escaping from their doomed warren, won him both the Carnegie medal and the Guardian children’s prize. “It was rather difficult to start with,” he says. “I was 52 when I discovered I could write. I wish I’d known a bit earlier. I never thought of myself as a writer until I became one.”

To create his rabbit characters, he drew from people he had met and from the world of literature. Bigwig was based on an officer he had known in the war, a great fighter at his best when given explicit orders, while Fiver was derived from Cassandra, the figure from Greek mythology who had the power of prophecy. Kipling, writes Adams in an introduction to a beautifully illustrated new edition of the book, showed him that he could let his rabbits think and talk, but keep them otherwise entirely rabbity. Meanwhile, RM Lockley’s The Private Life of the Rabbit taught him about the animal’s characteristics. And Watership Down is a real place, in Hampshire.

At first, Adams had no idea he had written something special. He sent the manuscript out to publishers, seven of whom rejected it. “It happened time after time. I got so disappointed I couldn’t bear to take the manuscript back. I used to send Elizabeth to collect it.” Eventually, he sent the pages to the small publisher Rex Collings, who took it on. The first print run, in 1972, was just 2,500 copies – all Collings could afford. But the reviews were staggering, and it has now sold in the millions. “I’ve become a different person with that book. It’s there and I’m behind it, somehow. I don’t go around swanking about it, I try not to. But I have become the person who told those stories.”

Interpretation after interpretation has been laid on Watership Down, from allegory to a take on religion. Adams rejects them all. “It was meant to be just a story, and it remains that. A story, a jolly good story I must admit, but it remains a story. It’s not meant to be a parable. That’s important, I think. Its power and strength come from being a story told in the car.”

They might just be rabbits, but the protagonists of Watership Down travel to some dark places, from Bigwig getting trapped in the snare (a harrowing, unforgettable scene that Elizabeth tried to convince her husband to remove) to the young bucks drawn into the creepy, cult-like atmosphere of Cowslip’s warren. And then, of course, there are the confrontations with the scheming rabbit General Woundwort, founder of the Efrafa warren. “Yes, I remain pleased with Woundwort. He is terrifying. He’s the making of it, really. It wouldn’t be the same without him.”

He does his reciting-from-memory thing again. “The text says, ‘General Woundwort was never seen again.’ But he has spoken of being able to survive in the wild. And it says, ‘So it may perhaps be that, after all, that extraordinary rabbit really did wander away to live his fierce life somewhere else.’”

Before Adams had even found a publisher, he had already started on Shardik, his remarkable tale of a wounded bear who is found by a hunter and believed to be the reincarnation of God. Paid homage to by Stephen King in his Dark Tower series, the book has also just been reissued, the cover bearing a quote hailing it as his masterpiece. Adams isn’t quite so sure about that today. “Shardik – it’s readable, isn’t it?” he says, adding that his best work might be The Plague Dogs, about two hounds on the run from a horrific animal-research centre.

Adams was still working at the civil service when he wrote Shardik, and his family remember him striding around the house muttering the inexplicable phrase “Shardik, the power of God!” under his breath. “I was a different person in those days,” he says. “I probably seem very self-confident, probably quite annoying, to you now, but in those days I wasn’t self-confident. It was a struggle to get anything done and know it was all right.”

Collings published Shardik to a positive, if more muted, reception. “They were all expecting more rabbits, but of course they didn’t get them. That was why Shardik, well, it wasn’t a failure, but for a lot of people it wasn’t what they were expecting. It didn’t get the reception it might have.”

The writing got easier. Adams even wrote a prequel to Shardik about a girl who is sold into slavery (there’s lots of sex). Most recent was Daniel, his 2006 novel about a boy born on a plantation in 1759, which he isn’t entirely impressed by today. “I just thought I’d better try to write a novel about real people in a real setting, so I made myself do it, but I didn’t expect it to be an outstanding success, and it isn’t. I can’t write about real people. I proved that to myself with Daniel. I’m a fantasist.”

Nothing, anyway, has lived up to his debut. “I try to look at it in a positive way, to say to myself, ‘Look at Watership Down – if you can do that, you can do any ruddy thing.’ Of course you can’t expect to have another success like that, but it does give you the confidence and the enjoyment to go on writing.”

Today, he works every other day. “I’m ancient now. I couldn’t write under the sort of pressure I had with my early books.” Despite his experience of Daniel, the work in progress is about a boy, kidnapped when he was younger, now a cabin boy with the Spanish armada. “I mean to tell the story from the boy’s point of view, with plenty of action,” he says. “And plenty of, yes, horrible things.”

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment