2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

Review by Penelope Gilliatt

AFTER MAN

by Penelope Gilliatt

I think Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is some sort of great film, and an unforgettable endeavor. Technically and imaginatively, what he put into it is staggering: five years of his life; his novel and screenplay, with Arthur C. Clarke; his production, his direction, his special effects; his humor and stamina and particular disquiet. The film is not only hideously funny — like Dr. Strangelove — about human speech and response at a point where they have begun to seem computerized, and where more and more people sound like recordings left on while the soul is out. It is also a uniquely poetic piece of sci-fi, made by a man who truly possesses the drives of both science and fiction.

Kubrick’s tale of quest in the year 2001, which eventually takes us to the Moon and Jupiter, begins on prehistoric Earth. Tapirs snuffle over the Valhalla landscape, and a leopard with broken-glass eyes guards the carcass of a zebra in the moonlight. Crowds of apes, scratching and ganging up, are disturbingly represented not by real animals, like the others, but by actors in costume. They are on the brink of evolving into men, and the overlap is horrible. Their stalking movements are already exactly ours: an old tramp’s, drunk, at the end of his tether and fighting mad. Brute fear has been refined into the infinitely more painful human capacity for dread. The creatures are so nearly human that they have religious impulses. A slab that they suddenly come upon sends them into panicked reverence as they touch it, and the film emits a colossal sacred din of chanting. The shock of faith boots them forward a few thousand years, and one of the apes, squatting in front of a bed of bones, picks up his first weapon. In slow motion, the hairy arm swings up into an empty frame and then down again, and the smashed bones bounce into the air. What makes him do it? Curiosity? What makes people destroy anything, or throw away the known, or set off in spaceships? To see what Nothing feels like, driven by some bedrock instinct that it is time for something else? The last bone thrown in the air is matched, in the next cut, to a spaceship at the same angle. It is now 2001. The race has survived thirty-three years more without extinction, though not with any growth of spirit. There are no Negroes in this vision of America’s space program; conversation with Russian scientists is brittle with mannerly terror, and the Chinese can still be dealt with only by pretending they’re not there. But technological man has advanced no end. A space way station shaped like a Ferris wheel and housing a hotel called the Orbiter Hilton hangs off the pocked old cheek of Earth. The soundtrack, bless its sour heart, meanwhile thumps out The Blue Danube, to confer a little of the courtliness of bygone years on space. The civilization that Kubrick sees coming has the brains of a nuclear physicist and the sensibility of an airline hostess smiling through an oxygen-mask demonstration.

Kubrick is a clever man. The grim joke is that life in 2001 is only faintly more gruesome in its details of sophisticated affluence than it is now. When we first meet William Sylvester as a space scientist, for instance, he is in transit to the Moon, via the Orbiter Hilton, to investigate another of the mysterious slabs. The heroic man of intellect is given a nice meal on the way — a row of spacecraft foods to suck through straws out of little plastic cartons, each decorated with a picture of sweet corn, or whatever, to tell him that sweet corn is what he is sucking. He is really going through very much the same ersatz form of the experience of being well looked after as the foreigner who arrives at an airport now with a couple of babies, reads in five or six languages on luggage carts that he is welcome, and then finds that he has to manage his luggage and the babies without actual help from a porter. The scientist of 2001 is only more inured. He takes the inanities of space personnel on the chin. “Did you have a pleasant flight?” Smile, smile. Another smile, possibly pre-filmed, from a girl on a television monitor handling voice-print identification at Immigration. The Orbiter Hilton is decorated in fresh plumbing-white, with magenta armchairs shaped like pelvic bones scattered through it. Artificial gravity is provided by centrifugal force; inside the rotating Ferris wheel people have weight. The architecture gives the white floor of the Orbiter Hilton’s conversation area quite a gradient, but no one lets slip a sign of humor about the slant. The citizens of 2001 have forgotten how to joke and resist, just as they have forgotten how to chat, speculate, grow intimate, or interest one another. But otherwise everything is splendid. They lack the mind for acknowledging that they have managed to diminish outer space into the ultimate in humdrum, or for dealing with the fact that they are spent and insufficient, like the apes.

The film is hypnotically entertaining, and it is funny without once being gaggy, but it is also rather harrowing. It is as eloquent about what is missing from the people of 2001 as about what is there. The characters seem isolated almost beyond endurance. Even in the most absurd scenes, there is often a fugitive melancholy — as astronauts solemnly watch themselves on homey B.B.C. interviews seen millions of miles from Earth, for instance, or as they burn their fingers on their space meals, prepared with the utmost scientific care but a shade too hot to touch, or as they plod around a centrifuge to get some exercise, shadowboxing alone past white coffins where the rest of the Crew hibernates in deep freeze. Separation from other people is total and unmentioned. Kubrick has no characters in the film who are sexually related, nor any close friends. Communication is stuffy and guarded, made at the level of men together on committees or of someone being interviewed. The space scientist telephones his daughter by television for her birthday, but he has nothing to say, and his wife is out; an astronaut on the nine month mission to Jupiter gets a prerecorded TV birthday message from his parents. That’s the sum of intimacy. No enjoyment — only the mechanical celebration of the anniversaries of days when the race perpetuated itself. Again, another astronaut, played by Keir Dullea, takes a considerable risk to try to save a fellow-spaceman, but you feel it hasn’t anything to do with affection or with courage. He has simply been trained to save an expensive colleague by a society that has slaughtered instinct. Fortitude is a matter of programming, and companionship seems lost. There remains only longing, and this is buried under banality, for English has finally been booted to death. Even informally, people say “Will that suffice?” for “Will that do?” The computer on the Jupiter spaceship — a chatty, fussy genius called HAL, which has nice manners and a rather querulous need for reassurance about being wanted — talks more like a human being than any human being does in the picture. HAL runs the craft, watches over the rotating quota of men in deep freeze, and plays chess. He gives a lot of thought to how he strikes others, and sometimes carries on about himself like a mother fussing on the telephone to keep a bored grown child hanging on. At a low ebb and growing paranoid, he tells a hysterical lie about a faulty piece of equipment to recover the crew’s respect, but a less emotional twin computer on Earth coolly picks him up on the judgment and degradingly defines it as a mistake. HAL, his mimic humanness perfected, detests the witnesses of his humiliation and restores his ego by vengeance. He manages to kill all the astronauts but Keir Dullea, including the hibernating crew members, who die in the most chillingly modern death scene imaginable: warning lights simply signal “Computer Malfunction,” and sets off electrophysiological needles above the sleepers run amok on the graphs and then record the straight lines of extinction. The survivor of HAL’s marauding self-justification, alone on the craft, has to battle his way into the computer’s red-flashing brain, which is the size of your living room, to unscrew the high cerebral functions. HAL’s sophisticated voice gradually slows and he loses his grip. All he can remember in the end is how to sing “Daisy” — which he was taught at the start of his training long ago — grinding down like an old phonograph. It is an upsetting image of human decay from command into senility. Kubrick makes it seem a lot worse than a berserk computer being controlled with a screwdriver.

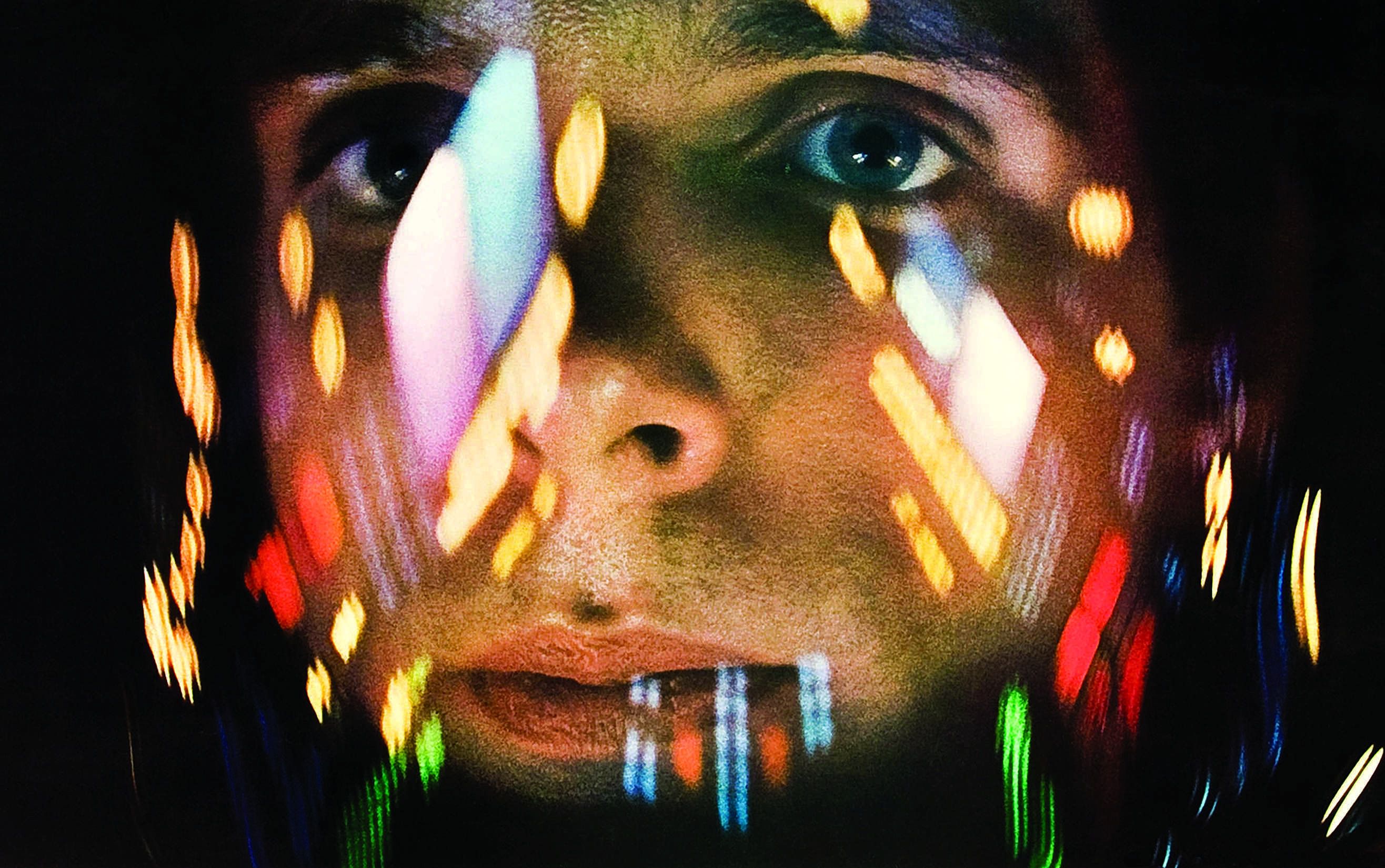

The startling metaphysics of the picture are symbolized in the slabs. It is curious that we should all still be so subconsciously trained in apparently distant imagery. Even to atheists, the slabs wouldn’t look simply like girders. They immediately have to do with Mosaic tablets or druidical stones. Four million years ago, says the story, an extraterrestrial intelligence existed. The slabs are its manifest sentinels. The one we first saw on prehistoric Earth is like the one discovered in 2001 on the Moon. The lunar finding sends out an upper- harmonic shriek to Jupiter and puts the scientists on the trail of the forces of creation. The surviving astronaut goes on alone and Jupiter’s influence pulls him into a world where time and space are relative in ways beyond Einstein. Physically almost pulped, seeing visions of the planet’s surface that are like chloroform nightmares and that sometimes turn into closeups of his own agonized eyeball and eardrum, he then suddenly lands, and he is in a tranquilly furnished repro Louis XVI room. The shot of it through the window of his space pod is one of the most heavily charged things in the whole picture, though its effect and its logic are hard to explain.

In the strange, fake room, which is movingly conventional, as if the most that the ill man’s imagination can manage in conceiving a better world beyond the infinite is to recollect something he has once been taught to see as beautiful in a grand decorating magazine, time jumps and things disappear. The barely surviving astronaut sees an old grandee from the back, dining on the one decent meal in the film; and when the man turns around it is the astronaut himself in old age. The noise of the chair moving on the white marble in the silence is typical of the brilliantly selective soundtrack. The old man drops his wineglass, and then sees himself bald and dying on the bed, twenty or thirty years older still, with his hand up to another of the slabs, which has appeared in the room and stands more clearly than ever for the forces of change. Destruction and creation coexist in them. They are like Siva. The last shot of the man is totally transcendental, but in spite of my resistance to mysticism I found it stirring. It shows an X-raylike image of the dead man’s skull re-created as a baby, and approaching Earth. His eyes are enormous. He looks like a mutant. Perhaps he is the first of the needed new species.

It might seem a risky notion to drive sci-fi into magic. But, as with Strangelove, Kubrick has gone too far and made it the poetically just place to go. He and his collaborator have found a powerful idea to impel space conquerors whom puny times have robbed of much curiosity. The hunt for the remnant of a civilization that has been signaling the existence of its intelligence to the future for four million years, tirelessly stating the fact that it occurred, turns the shots of emptied, comic, ludicrously dehumanized men into something more poignant. There is a hidden parallel to the shot of the ape’s arm swinging up into the empty frame with its first weapon, enthralled by the liberation of something new to do; I keep remembering the shot of the space scientist asleep in a craft with the “Weightless Conditions” sign turned on, his body fixed down by his safety belt while one arm floats free in the air.

Kubrick’s tale of quest in the year 2001, which eventually takes us to the Moon and Jupiter, begins on prehistoric Earth. Tapirs snuffle over the Valhalla landscape, and a leopard with broken-glass eyes guards the carcass of a zebra in the moonlight. Crowds of apes, scratching and ganging up, are disturbingly represented not by real animals, like the others, but by actors in costume. They are on the brink of evolving into men, and the overlap is horrible. Their stalking movements are already exactly ours: an old tramp’s, drunk, at the end of his tether and fighting mad. Brute fear has been refined into the infinitely more painful human capacity for dread. The creatures are so nearly human that they have religious impulses. A slab that they suddenly come upon sends them into panicked reverence as they touch it, and the film emits a colossal sacred din of chanting. The shock of faith boots them forward a few thousand years, and one of the apes, squatting in front of a bed of bones, picks up his first weapon. In slow motion, the hairy arm swings up into an empty frame and then down again, and the smashed bones bounce into the air. What makes him do it? Curiosity? What makes people destroy anything, or throw away the known, or set off in spaceships? To see what Nothing feels like, driven by some bedrock instinct that it is time for something else? The last bone thrown in the air is matched, in the next cut, to a spaceship at the same angle. It is now 2001. The race has survived thirty-three years more without extinction, though not with any growth of spirit. There are no Negroes in this vision of America’s space program; conversation with Russian scientists is brittle with mannerly terror, and the Chinese can still be dealt with only by pretending they’re not there. But technological man has advanced no end. A space way station shaped like a Ferris wheel and housing a hotel called the Orbiter Hilton hangs off the pocked old cheek of Earth. The soundtrack, bless its sour heart, meanwhile thumps out The Blue Danube, to confer a little of the courtliness of bygone years on space. The civilization that Kubrick sees coming has the brains of a nuclear physicist and the sensibility of an airline hostess smiling through an oxygen-mask demonstration.

Kubrick is a clever man. The grim joke is that life in 2001 is only faintly more gruesome in its details of sophisticated affluence than it is now. When we first meet William Sylvester as a space scientist, for instance, he is in transit to the Moon, via the Orbiter Hilton, to investigate another of the mysterious slabs. The heroic man of intellect is given a nice meal on the way — a row of spacecraft foods to suck through straws out of little plastic cartons, each decorated with a picture of sweet corn, or whatever, to tell him that sweet corn is what he is sucking. He is really going through very much the same ersatz form of the experience of being well looked after as the foreigner who arrives at an airport now with a couple of babies, reads in five or six languages on luggage carts that he is welcome, and then finds that he has to manage his luggage and the babies without actual help from a porter. The scientist of 2001 is only more inured. He takes the inanities of space personnel on the chin. “Did you have a pleasant flight?” Smile, smile. Another smile, possibly pre-filmed, from a girl on a television monitor handling voice-print identification at Immigration. The Orbiter Hilton is decorated in fresh plumbing-white, with magenta armchairs shaped like pelvic bones scattered through it. Artificial gravity is provided by centrifugal force; inside the rotating Ferris wheel people have weight. The architecture gives the white floor of the Orbiter Hilton’s conversation area quite a gradient, but no one lets slip a sign of humor about the slant. The citizens of 2001 have forgotten how to joke and resist, just as they have forgotten how to chat, speculate, grow intimate, or interest one another. But otherwise everything is splendid. They lack the mind for acknowledging that they have managed to diminish outer space into the ultimate in humdrum, or for dealing with the fact that they are spent and insufficient, like the apes.

The film is hypnotically entertaining, and it is funny without once being gaggy, but it is also rather harrowing. It is as eloquent about what is missing from the people of 2001 as about what is there. The characters seem isolated almost beyond endurance. Even in the most absurd scenes, there is often a fugitive melancholy — as astronauts solemnly watch themselves on homey B.B.C. interviews seen millions of miles from Earth, for instance, or as they burn their fingers on their space meals, prepared with the utmost scientific care but a shade too hot to touch, or as they plod around a centrifuge to get some exercise, shadowboxing alone past white coffins where the rest of the Crew hibernates in deep freeze. Separation from other people is total and unmentioned. Kubrick has no characters in the film who are sexually related, nor any close friends. Communication is stuffy and guarded, made at the level of men together on committees or of someone being interviewed. The space scientist telephones his daughter by television for her birthday, but he has nothing to say, and his wife is out; an astronaut on the nine month mission to Jupiter gets a prerecorded TV birthday message from his parents. That’s the sum of intimacy. No enjoyment — only the mechanical celebration of the anniversaries of days when the race perpetuated itself. Again, another astronaut, played by Keir Dullea, takes a considerable risk to try to save a fellow-spaceman, but you feel it hasn’t anything to do with affection or with courage. He has simply been trained to save an expensive colleague by a society that has slaughtered instinct. Fortitude is a matter of programming, and companionship seems lost. There remains only longing, and this is buried under banality, for English has finally been booted to death. Even informally, people say “Will that suffice?” for “Will that do?” The computer on the Jupiter spaceship — a chatty, fussy genius called HAL, which has nice manners and a rather querulous need for reassurance about being wanted — talks more like a human being than any human being does in the picture. HAL runs the craft, watches over the rotating quota of men in deep freeze, and plays chess. He gives a lot of thought to how he strikes others, and sometimes carries on about himself like a mother fussing on the telephone to keep a bored grown child hanging on. At a low ebb and growing paranoid, he tells a hysterical lie about a faulty piece of equipment to recover the crew’s respect, but a less emotional twin computer on Earth coolly picks him up on the judgment and degradingly defines it as a mistake. HAL, his mimic humanness perfected, detests the witnesses of his humiliation and restores his ego by vengeance. He manages to kill all the astronauts but Keir Dullea, including the hibernating crew members, who die in the most chillingly modern death scene imaginable: warning lights simply signal “Computer Malfunction,” and sets off electrophysiological needles above the sleepers run amok on the graphs and then record the straight lines of extinction. The survivor of HAL’s marauding self-justification, alone on the craft, has to battle his way into the computer’s red-flashing brain, which is the size of your living room, to unscrew the high cerebral functions. HAL’s sophisticated voice gradually slows and he loses his grip. All he can remember in the end is how to sing “Daisy” — which he was taught at the start of his training long ago — grinding down like an old phonograph. It is an upsetting image of human decay from command into senility. Kubrick makes it seem a lot worse than a berserk computer being controlled with a screwdriver.

The startling metaphysics of the picture are symbolized in the slabs. It is curious that we should all still be so subconsciously trained in apparently distant imagery. Even to atheists, the slabs wouldn’t look simply like girders. They immediately have to do with Mosaic tablets or druidical stones. Four million years ago, says the story, an extraterrestrial intelligence existed. The slabs are its manifest sentinels. The one we first saw on prehistoric Earth is like the one discovered in 2001 on the Moon. The lunar finding sends out an upper- harmonic shriek to Jupiter and puts the scientists on the trail of the forces of creation. The surviving astronaut goes on alone and Jupiter’s influence pulls him into a world where time and space are relative in ways beyond Einstein. Physically almost pulped, seeing visions of the planet’s surface that are like chloroform nightmares and that sometimes turn into closeups of his own agonized eyeball and eardrum, he then suddenly lands, and he is in a tranquilly furnished repro Louis XVI room. The shot of it through the window of his space pod is one of the most heavily charged things in the whole picture, though its effect and its logic are hard to explain.

In the strange, fake room, which is movingly conventional, as if the most that the ill man’s imagination can manage in conceiving a better world beyond the infinite is to recollect something he has once been taught to see as beautiful in a grand decorating magazine, time jumps and things disappear. The barely surviving astronaut sees an old grandee from the back, dining on the one decent meal in the film; and when the man turns around it is the astronaut himself in old age. The noise of the chair moving on the white marble in the silence is typical of the brilliantly selective soundtrack. The old man drops his wineglass, and then sees himself bald and dying on the bed, twenty or thirty years older still, with his hand up to another of the slabs, which has appeared in the room and stands more clearly than ever for the forces of change. Destruction and creation coexist in them. They are like Siva. The last shot of the man is totally transcendental, but in spite of my resistance to mysticism I found it stirring. It shows an X-raylike image of the dead man’s skull re-created as a baby, and approaching Earth. His eyes are enormous. He looks like a mutant. Perhaps he is the first of the needed new species.

It might seem a risky notion to drive sci-fi into magic. But, as with Strangelove, Kubrick has gone too far and made it the poetically just place to go. He and his collaborator have found a powerful idea to impel space conquerors whom puny times have robbed of much curiosity. The hunt for the remnant of a civilization that has been signaling the existence of its intelligence to the future for four million years, tirelessly stating the fact that it occurred, turns the shots of emptied, comic, ludicrously dehumanized men into something more poignant. There is a hidden parallel to the shot of the ape’s arm swinging up into the empty frame with its first weapon, enthralled by the liberation of something new to do; I keep remembering the shot of the space scientist asleep in a craft with the “Weightless Conditions” sign turned on, his body fixed down by his safety belt while one arm floats free in the air.

The New Yorker, 13th April 1968

No comments:

Post a Comment