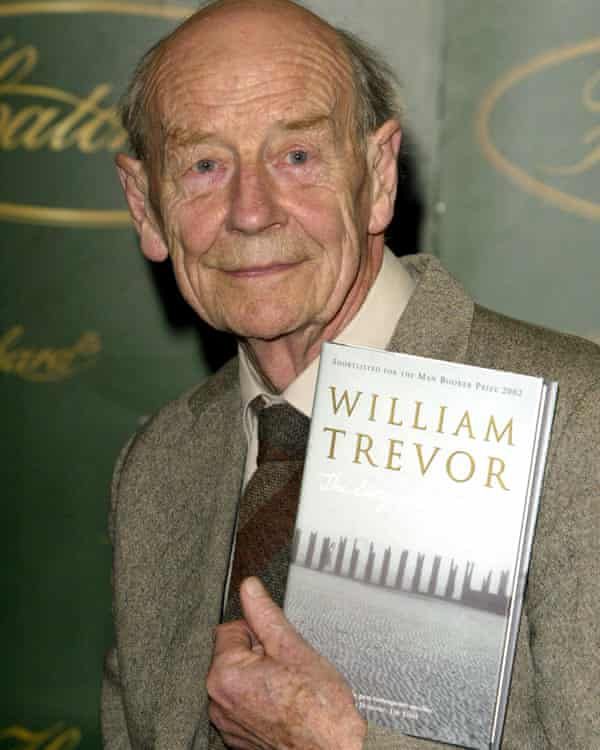

Julian Barnes on William Trevor's final stories – a master of the short form

The great Irish writer displays all his trademark evasive precision in Last Stories, a posthumous collection

Julian BarnesSaturday 19 May 2018

W

My wife, who was his long-term literary agent, told me that he liked to sit on park benches and eavesdrop on conversations; but that he never wanted to listen to a whole story, so would get up and move on as soon as he had heard the small amount he needed to trigger his further imaginings. This always struck me as a perfect example of how a fiction writer often works. You need a little, not a lot; and there is nothing more unhelpful than the guy (and it always is a guy) who greets you with: “I’ve got a great story you could use.”

I was slow getting to Trevor’s work, put off in my early 20s by a theatrical adaptation in some cavernous provincial theatre of The Old Boys. What was it about, I wondered, and why were people laughing at all these old (or old-looking) actors? It was my fault, doubtless; or at least, my youth’s fault. Trevor writes as an adult for adults, expecting you to understand both life and prose; he is the subtlest purveyor of the partial truths we humans mostly live by. And when I finally read The Old Boys, I saw it as one of the rare examples of a novelist early in his career taking on the question of age, and emotion in age, long before he is personally cognisant of it; Trevor does so with the same kind of wiry savagery displayed by Muriel Spark in Memento Mori (his second novel, her third). He understood and could ventriloquise young and old, male and female; village, town and country; the socially low, middle and occasionally high. As for the young: 1976’s The Children of Dynmouth features one of the creepiest of manipulative boys in the whole of fiction; shelve it alongside The Turn of the Screw.

Fiction writers can be located on various spectra. By style: the range goes from the look-at-me merchants, whose every phrase gleams like a monogrammed slipper, to those who operate with discretion, quietness, invisibility. By authorial control: should characters expect to be whipped like galley slaves, as Nabokov whimsically put it, or to be empathetically inhabited and animated? By public visibility: from writers who act as public figures, make political or social interventions, and delight in social media, to those “merely” absorbed in the life around them, about which they issue occasional bulletins. Connected to this, there are writers who invite our curiosity about their own lives, personality and sexual doings, versus those who self-effacingly insist that the work is sufficient unto itself. On all of these spectra, Trevor belongs on the far right-hand side. You can’t imagine him, even if he had lived another 50 years, ever having a Google alert on himself.

There is another division between fiction writers, of a more ruthlessly binary kind. There are those who are essentially novelists but who occasionally lapse into the short story; and those who are short story writers but who may veer into the novel. The novelists often fail at the shorter form’s difficult mix of spareness and intensity; the short story writers often sway and ramble when let loose in larger acres. Trevor was one of the very rare exceptions, genuinely ambidextrous in his 14 novels, two novellas and 13 collections of stories.

Many of these Last Stories – published after his death in 2016 on what would have been Trevor’s 90th birthday – begin at a point where the characters’ lives might seem to be over, or at least much diminished. They start with a death, a widowing, the end of a marriage, a sudden acknowledgment that henceforth the past rules. A piano teacher realises that all the main events of her life – a father’s death, a secret love affair – have taken place in the very room where she now gives lessons. A publisher’s reader, whose husband was stolen years ago by her best friend, now trusts to a stable routine for getting through her “leftover life to kill”. Some protagonists have walked away from their previous commitments; others have been the ones abandoned. There is much inner solitude in this world; happiness is temporary and conditional; often there has been damage a long way back, damage that cannot be mended. And having the best of intentions may be a recipe for disaster. In “An Idyll in Winter”, a young tutor stirs the imagination of a 12-year-old girl in a Big House on the Yorkshire Moors; a decade and more later, he returns, now a cartographer, married with two children, while she, still unattached, runs the farm after the death of her parents. He visits, leaves, returns, stays, vacillates, lets down both women, and leaves for ever. His desire not to hurt hurts; his marriage dies. Meanwhile, the estate workers silently pity their employer, and she cannot explain to them how love will continue in the man’s absence, despite his absence, even perhaps because of his absence. Her love “will not wither ... there’ll be no long slow dying, or love made ordinary”. This may sound romantic, but in fact offers a terrible choice: the presence and acceptance of love, then its descent into familiarity and ordinariness, versus the absence or refusal of love and its vivid continuation.

Yet the word “choice” implies agency. Trevor’s characters rarely choose what happens to them; life chooses for them. What they want, or feel they want, does not govern what they get – or only for a brief, illusory time. After that they are delivered back into emotional marginality, glancing non-relationships and the dubious certitudes of memory. There are also slippages of identity and function to be endured. A picture restorer struck by bouts of amnesia wanders haltingly through his own city; a pair of itinerant “Polish painters” turn out to be something else entirely; a daughter, growing up with a father, assuming her absent mother to be dead, turns out to have a different origin story. Trevor’s characters are often lone, or alone, or lonely, even – especially – if they are in a relationship. And there are doubts and ambiguities at every turn. Did they go to bed together or not? Was it accident or suicide? Where does fault and responsibility actually lie? Trevor’s fiction is full of precise evasions – and evasive precisions. As VS Pritchett wrote of Chekhov, he “accepts all contradictions”.

Take “Mrs Crasthorpe”, one of the most powerful stories in the book. It is 22 pages long, and intercuts two lives – a frequent Trevor ploy. It opens with the title character, a “lone mourner” at her husband’s funeral. But – atypically – Mrs Crasthorpe defies her loneness, and declines to accept that her life is over; she imagines herself “always a rosebud”, and proposes to “relish” her widowhood. Living by cheerful pretence, she has removed 14 years from her age, and tells no one about her illegitimate (criminal, banged-up) son, or the lovers she took during her marriage. Meanwhile, elsewhere in London, a specialist printer called Etheridge tends his dying wife. After her death he moves to near Regent’s Park. One day, he is accosted in the street by Mrs Crasthorpe, who asks him for directions to a road that doesn’t exist. Another pretence, designed to delay and engage a polite Englishman who will naturally attempt to help. It is a trick that has worked for her before.

We think we can guess where the story might be going – at least, in other hands. She, being cheerful and attractive, will divert him from his grief, draw him out, attach him to her, and make him reliant, if at first only sexually, on her. He will not discover her true nature until it is too late; by which time, even so, she might succeed in making him happy.

But this is not Trevor’s way, nor is it his reading of life. A while later, Etheridge is sitting in a cafe, only to find Mrs Crasthorpe at the next table, pretending to half-recognise him. She is both lush and delicate; she employs the charms and conversational ploys that have usually worked in the past. She has a way of implying that they know one another a little better than they actually do. As they sit there, she muses on this “attractive stranger ... whom she’d made herself love a little”.

Naturally, the reader feels queasily apprehensive on Etheridge’s behalf. But Etheridge is not being charmed: quite the contrary. He finds Mrs Crasthorpe crassly babbling, and wonders if she might be drunk. But she is not stupid – or rather, she recognises when her prime tactic isn’t working. “We’re clearly not birds of a feather,” she remarks, “but if you should ever think we might know one another better …” and she writes her address down for him.

Again, another writer might leave it there – might leave it (in what would be a sub-Trevor way) with an ambiguous ending: might not Etheridge, in his loneliness, still succumb in one way or another? But this is the real Trevor. The story is in part a comparison of griefs: while Mrs Crasthorpe looks to enjoy “the pleasure of widowhood”, Etheridge knows only the uncomprehending regret of that state, and holds a “continuing anger at the careless greed of death”. When, years later, his eye catches the name “Crasthorpe” in a newspaper, he finds that “the curiosity Mrs Crasthorpe had failed to discover in her lifetime came now”. He seeks to imagine the rest of her life, “but too much was missing and he resisted further speculation. He sensed his own pity, not knowing why it was there.” But it is the reader’s pity too, as we go back over her story and better understand the panic behind the bravado, the yearning beneath the bright facade. And our eye returns to a few lines that we might have paused at but only half attended to: a moment when Mrs Crasthorpe cries, but not for effect:

She wept her private tears whenever she imagined the coat unbuttoned, the sudden twitch as it opened wide, the torch’s flash. She wept because she loved him as she did no other human being. She always had. She always would.

This relates to an incident whose significance escaped me for two readings. And it makes us understand that there is a third grief present in the story, this time for the living, not the dead. Trevor does not make a point of being demanding or obscure; but he is very subtle. And perhaps it is relevant that the 17th-century Etherege – with an E, not an I – wrote a play called She Would If She Could.

This pattern of readerly doubt and misprision is typical of a William Trevor story. We will be presented with an event – an accident in the street, a death, a funeral, a chance meeting, an abandonment – that will widen into a situation between two or more characters. There are only a limited number of fictional beginnings, and so we feel as if we have been here before. Automatically, we predict where the story might be going. But it doesn’t go where we predict, because, in a way we sense rather than observe, it has ceased to be a story. It has become life, and life wrongfoots us in stranger ways than fiction can. We submit to the deep, essential truth to life that Trevor has presented. And yet, at the same time, we realise it is still “only” a story.

None but those with a complete mastery of fiction can walk this line. William Trevor was not “an Irish Chekhov” or even “the Irish Chekhov”. He was and will remain the Irish William Trevor.

No comments:

Post a Comment