|

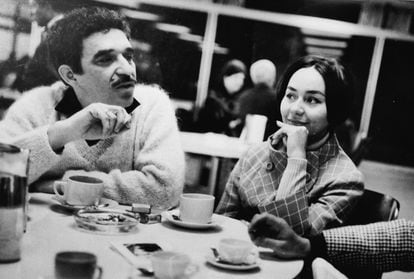

| Merces Barcha, Fidel Castro and Gabriel García Márquez |

The last days of Gabriel García Márquez

The son of the author of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ has written an intimate portrait of his father’s struggle with memory loss, and the death of his mother Mercedes Barcha, who passed away last year

Camila Osorio

México, 28 May 2021

When Gabriel García Márquez was writing One Hundred Years of Solitude in the 1960s, he said one of the most difficult moments was when he got to the death of the memorable Colonel Aureliano Buendía. “Gabo,” as the Colombian author was popularly known, left the study of his home in Mexico City and went to find his wife, Mercedes Barcha, in the bedroom. “I killed the colonel,” he told her, heartbroken. “She knew what that meant for him and they remained silent with the sad news,” says García Márquez’s son, Rodrigo García, remembering his parents’ grief. Now it is Rodrigo who is writing about his own grief in a new book about the death of his parents, Gabo y Mercedes: una despedida (or, Gabo and Mercedes: a farewell).

This loving tribute, published in Colombia and Spain by Random House, is the latest homage Rodrigo García has made to his father, who died in 2014, and his mother, Mercedes Barca, who passed away in August 2020. “My father always complained that one of the things that he hated most about death was the fact that it would be the only facet of his life that he wouldn’t be able to write about,” García wrote.

García’s book mixes the story of his parents’ final days with the deaths that García Márquez did indeed write about, such as that of independence leader Simón Bolívar in The General in His Labyrinth (“through the window he saw the diamond of Venus in the sky that was dying forever”), or the day that Úrsula Iguarán, the matriarch of One Hundred Years of Solitude, who “woke up dead on Maundy Thursday” – just like Márquez, who died on Maundy Thursday in 2014 at the age of 87.

“I didn’t have to think a lot to remember these passages,” says García in a press conference. “The obsession with loss and with death is very common among writers, it almost makes one thing that it’s part of a writer’s DNA: the obsession with loss and with the things that end, and how the end of life frames life experiences. That’s why I easily remembered all the deaths of his main characters.”

In the last few years, García, who is a film director, has been working on transforming his father’s books into movies: he is the executive producer of News of a Kidnapping (which is being produced by Amazon Prime and is currently being filmed in Colombia) and a Netflix-produced version of One Hundred Years of Solitude (which is in the pre-production stage). But the family has always been very careful not to reveal too much about their private life. “We are not public figures,” his mother, who was very protective of their privacy, used to say. In this way, the new book is a small window into the pain his parents suffered when García Márquez –who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 – was at the end of his life. “I know that I couldn’t publish these memories while she was able to read them,” says García. If his parents could read them now, “I would like to think they would be happy and proud, but I’m sure my mother would tell me, ‘what a gossip you are’,” he adds.

According to his son’s book, García Márquez struggled in his final days – his memories were beginning to slip away and he had a hard time recalling once-familiar faces. “Why is that woman here giving orders and running around the house as if it weren’t mine?” García Márquez says when he cannot recognize his wife in one of the passages in the book. “Who are those people on the other side of the room?” he asks a domestic worker of his two sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo. “This is not my home. I want to go home. To father’s home,” he says on another occasion, when he wants to return home to the house of his grandfather, a colonel who looked after him until he was eight years old and inspired the character of Aureliano Buendía.

But during his final days, García Márquez was also able to relive the most cherished moments of his childhood in Aracataca, the Colombian village where he was born in 1927. The award-winning author could also still recite from memory poems of the Spanish Golden Age. And when he could no longer do this, “he could still sing his favorite songs,” says García. The Nobel laureate spent his last days listening to vallenatos, the popular folk music from Colombia’s Caribbean region that he grew up with. “Even in the last months, when he couldn’t remember things, his eyes would light up with emotion with the first notes of a classical accordion,” writes García in the new book. “In the last few days, the nurses began to put on [vallenatos] at top volume in his bedroom, with the windows wide open.” The songs of Colombian vallenato composer Rafael Escalona filled the home in Mexico like lullabies to say goodbye. “They take me back to his past as nothing else can,” García writes.

Although the famous writer struggled with dementia, García says “the final stage [of his life] was easier.” “There is a terrible stage in which the person is aware that they are losing their memory. Seeing the person not only without their faculties, but also very anxious about losing them is awful and very hard,” he explains. “The final stage was sad, but calmer. He was calm, he wasn’t anxious, he was very distracted. He didn’t remember a lot of things, but he was good, peaceful, and that comforted us.”

Although most of García’s book is about his father’s death, the last chapter is dedicated to the passing of his mother, who was nicknamed La Gaba – a name García recognizes as “patriarchal.” “But despite everything, everyone who knew her knew that she had become a magnificent version of herself,” García writes in the book. He describes her as a “woman of her time”: a mother, wife and housewife who never went to university. Despite this, she was the one who managed her husband’s success, and was envied for her self-assuredness. In one scene in the book, García and his brother squirm in their seats when the Mexican president (who is not named, but for the time period would have been Enrique Peña Nieto), refers to the family as “the children and the widow.” In the scene, Mercedes Barcha threatens to “tell the first journalist who crossed her path that she was planning on getting married as soon as possible. Her last words on the subject are: ‘I am not a widow. I am myself,” García writes.

Mercedes Barcha died in 2020 in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, without the fanfare that surrounded Marquéz’s death. As her husband, García Márquez would have told his children that if they were to write about their mother’s death, they must ensure that the reader is left feeling completely stricken with grief. In the days after Barcha’s death, García says he kept waiting for her to call, a call in which she would ask him: “So, how was my death? No, calm down. Sit down. Tell it to me properly, without rushing.”

English version by Melissa Kitson.

No comments:

Post a Comment