Peter Hujar Captured

His Lover and Friends

in These Subversive Photographs

In the 1960s, artist lofts in downtown Manhattan became community hubs and creative incubators. established his second Factory on Union Square West. converted a Spring Street garment factory into a spare, minimalist mecca. At ’s East 12th Street apartment and studio space, NewYorkers both famous and anonymous lay on the photographer’s bed and stripped down for his camera.

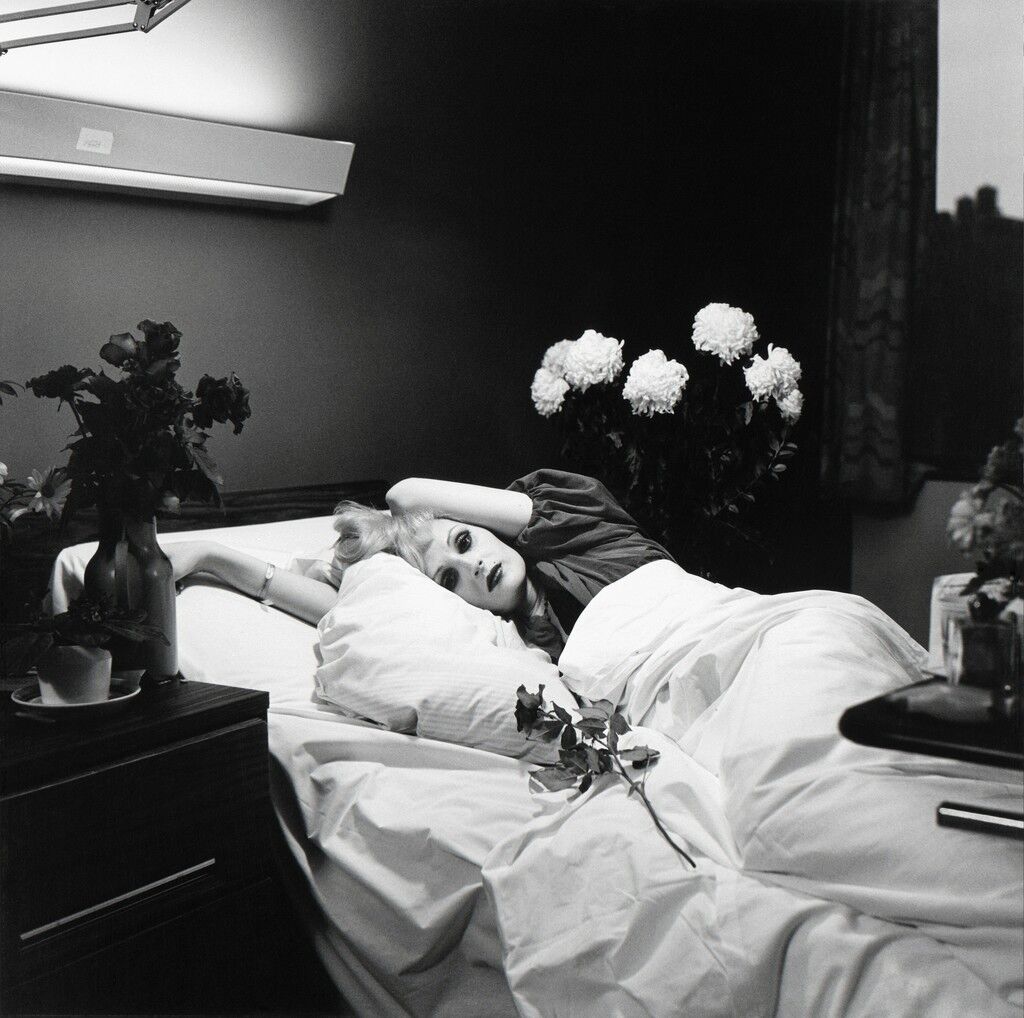

Before he died in 1987, at 53 years old, from AIDS-related pneumonia, Hujar took incisive studio portraits of drag queens, queer intellectuals, and artists; meditative photographs of the rippling Hudson River; male nudes dappled with light; and affectionate animal portraits that recalled his childhood years on a New Jersey farm. (In 2014, Hujar’s friend and fellow photographer said, “He’s the best photographer of animals I’ve ever met.”) Hujar photographed some of the most famous images of his lover and friend, the artist . He shot critic Susan Sontag and captured the last images of Warhol superstar Candy Darling from her hospital bed.

Hujar rose to prominence after fellow New York stalwarts and , and he influenced younger peers such as Goldin and . While he never achieved the same level of mainstream fame, his reputation among New York’s creative milieu preceded him. “I want to be discussed in hushed tones,” Hujar said of his posthumous legacy. “When people talk about me, I want them to be whispering.”

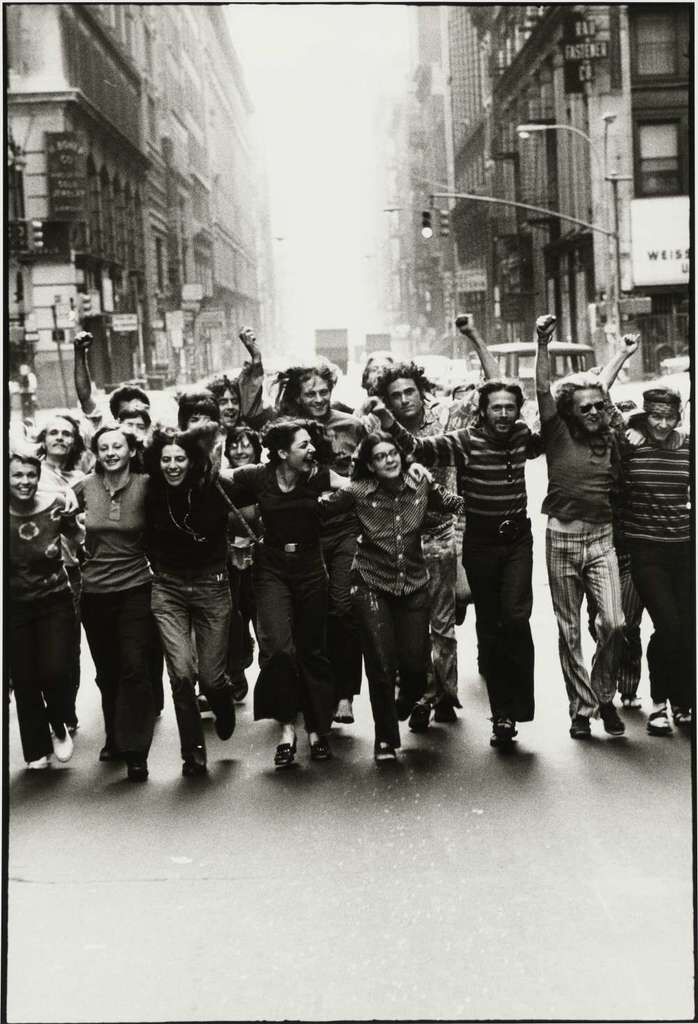

Pace Gallery’s new online exhibition “Cruising Utopia,” on view through July 28th, mixes Hujar’s portraits with his voyeuristic shots, taken while cruising the Christopher Street Piers. Here, we present six images from the show. All celebrate members of New York’s queer community and, incedentally, span from before the Stonewall riots to the year that the first AIDS case was discovered in the U.S.

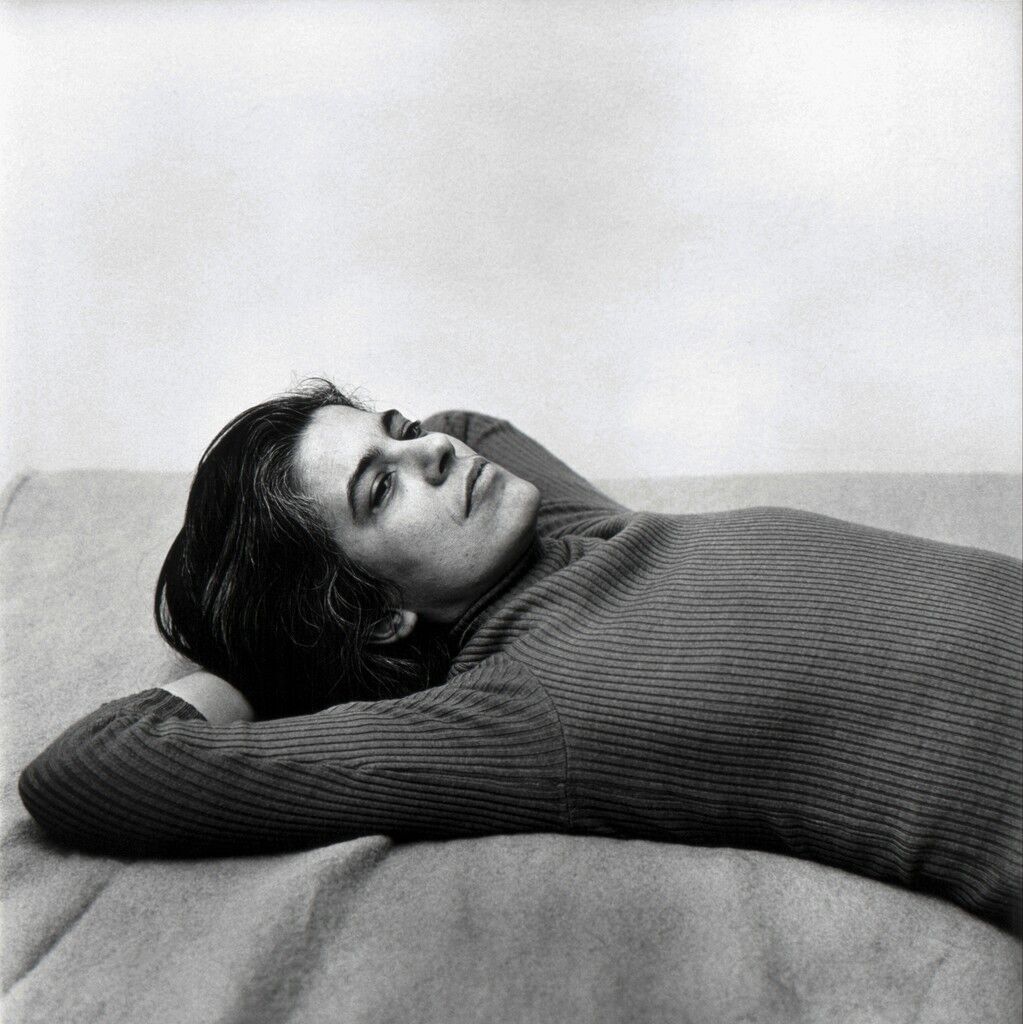

Susan Sontag (1975)

Hujar’s portrait of Susan Sontag reclining is arguably his most famous image. He shot the photograph while Sontag was regularly penning essays for the New York Review of Books about the photographic medium. In 1977, the essays were compiled and published in her famous treatise On Photography.

The pair met in 1963 and became close friends. Sontag took inspiration from Hujar’s images in her own writing, and wrote the introduction to his only book, Portraits in Life and Death, in 1976.

Hujar often asked his sitters to lie down so that he could find a revealing moment. Sontag did so in a ribbed turtleneck, her arms behind her head, the light diffused on her face as she gazed past the camera. In her soft grey portrait, the bed and wall become flat, neutral planes.

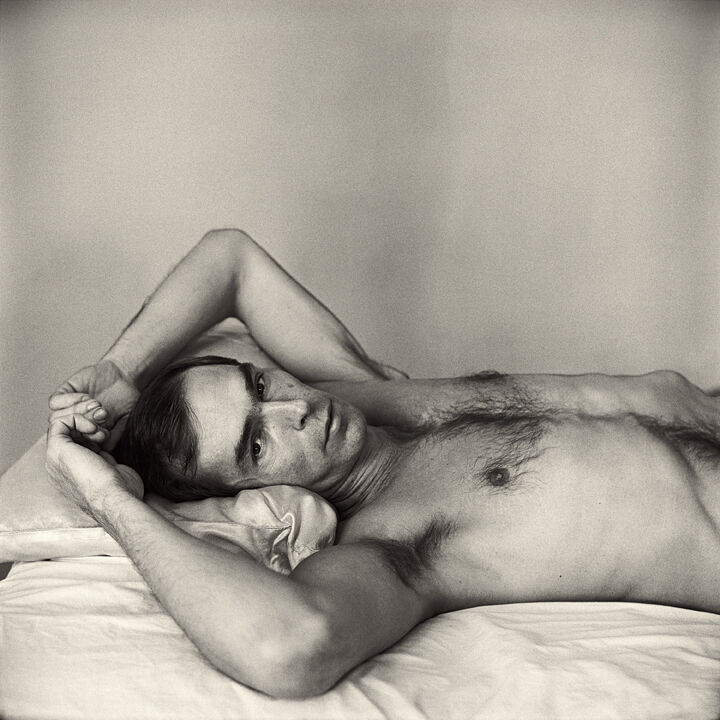

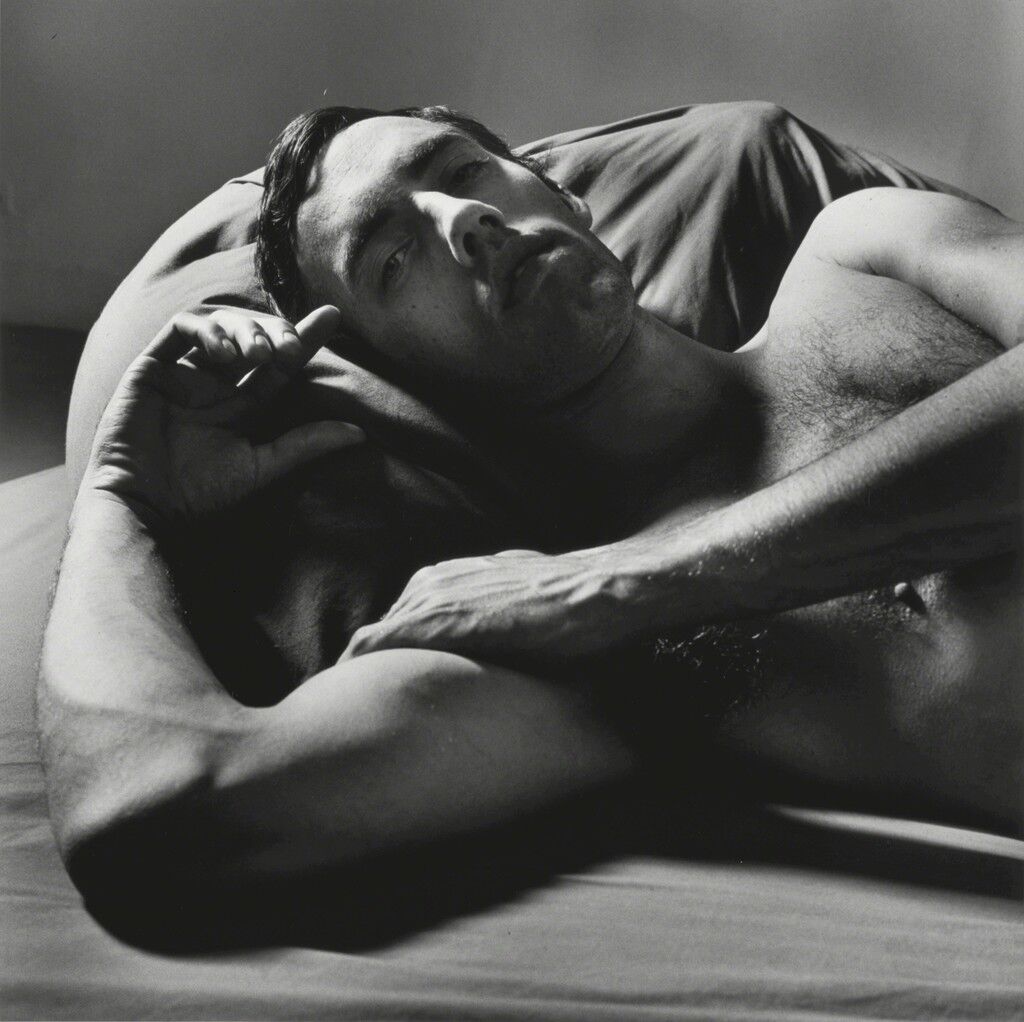

David Wojnarowicz Reclining (II) (1981)

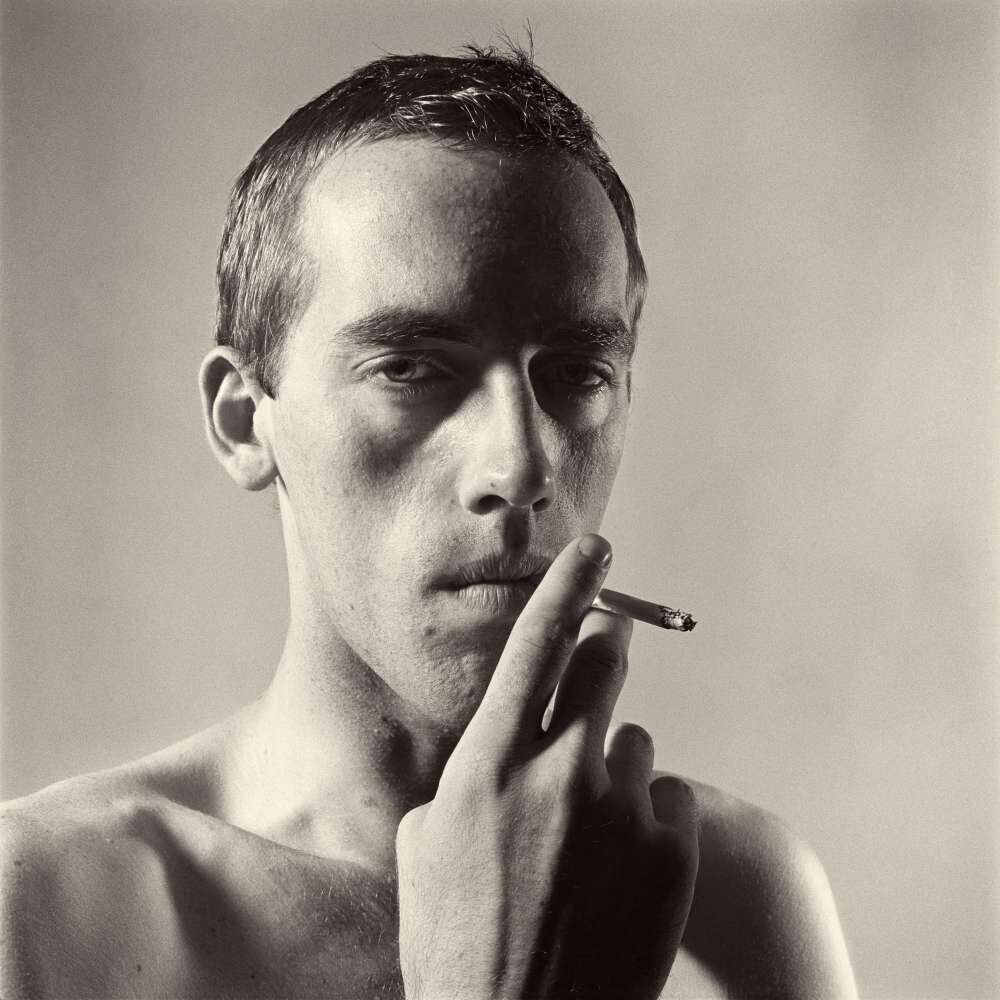

David Wojnarowicz Smoking (1981)

In 1980, Hujar met David Wojnarowicz in a bar while the latter was working as a hustler. Their relationship was dynamic: They were alternately lovers, friends, and companions during the last years of Hujar’s life. After becoming an artist and activist in his own right, Wojnarowicz died from AIDS complications in 1992, at age 37.

Six years after Hujar shot the famous Sontag photograph, Wojnarowicz lay in the same spot for a very different composition. In Hujar’s picture of Wojnarowicz reclining, the artist is propped up by a mussed pillow, his body tilted toward the viewer and dramatized with shadows.

Such sensuality rules many of Hujar’s images of Wojnarowicz. The photographer variously captured his subject smoking a cigarette and dispassionately eating an apple’s skin, the paring knife in his hand a sliver of danger.

In recent years, the creative pair has received renewed, linked attention. Wojnarowicz received a posthumous retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2018, and the Morgan Library and Museum mounted 140 prints of Hujar’s work for a traveling retrospective that contextualized Hujar’s work and gave him his due.

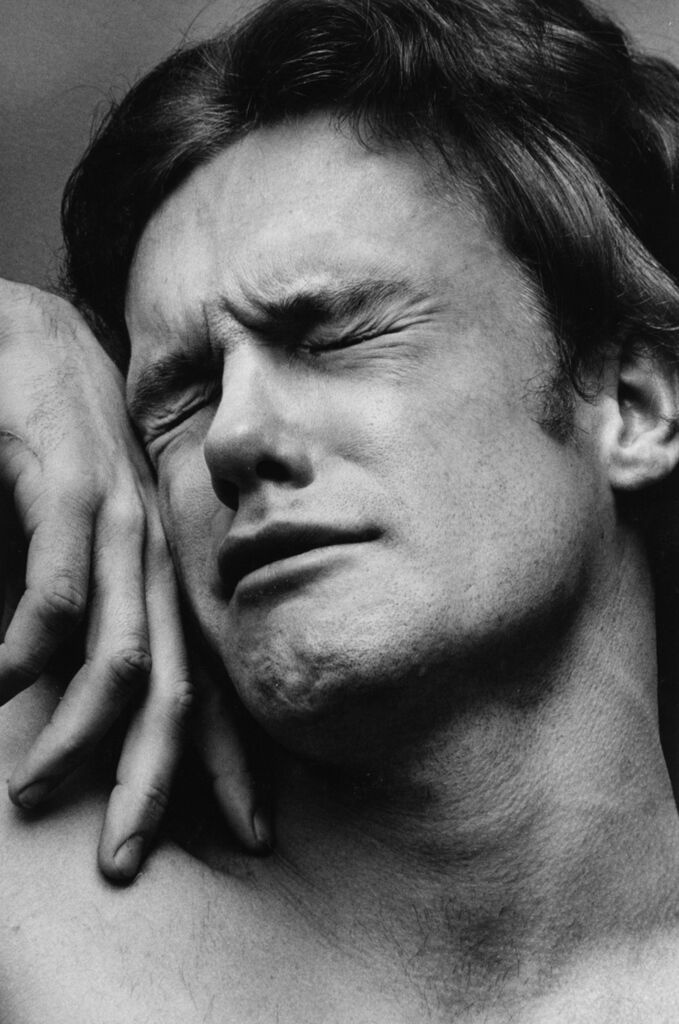

Orgasmic Man (1969)

In 1969, Hujar took bust portraits of different men mid-climax, capturing subjects at the peak of vulnerability and pleasure. The camera amplified the intensity of the moment and transformed a private act into an object for public viewing.

The works were included in the Barbican’s recent show “Masculinities,” which examined how masculinity has been performed and constructed through still and moving images. Orgasming for the camera may have been a performance in itself, but it was dropped as Hujar fired his shutter at the second his sitters abandoned themselves.

“Looking at his photographs of nude men…is the closest I ever came to experience what it is to inhabit male flesh,” Goldin once said.

In recent years, this particular photograph gained widespread notoriety as the cover image for Hanya Yanagihara’s best-selling novel A Little Life (2015).

Jay and Fernando [Two Men in Leather Kissing] (ca. 1966)

Hujar is often compared to his younger peer Mapplethorpe, as both depicted male sexuality and queer subcultures. But while Mapplethorpe combined a rigorous and pristine aesthetic with images that were often shocking—featuring self-penetration with a bullwhip or formally presenting leather daddies, for example—Hujar’s approach was more open and less focused on technical precision. His image of two leather-clad men kissing is tightly cropped and teems with the tension of their lips smashing together. The studio space was always a presence in Mapplethorpe’s images—suggesting desire and identity in a high art, and a performative setting—but in Hujar’s pictures, including Jay and Fernando, the location is neutral, which draws more focus to the encounter itself.

In 2018, Hujar’s friend, the social commentator Fran Lebowitz, spoke at length about Hujar’s relationship to Mapplethorpe, saying the younger photographer often looked to Hujar for guidance but took more than inspiration from him.

“Peter and I shared the distaste for Robert,” Lebowitz said. “But one of the reasons is that Peter thought Robert was silly, you know, which he was. And he thought that Robert copied him in certain ways, which of course he did.”

“Part of the reason [Hujar] was eclipsed was because of the great success of Mapplethorpe, who filled a niche and very spectacularly filled the image of a bad-boy photographer privy to those kinds of secrets of dark, nighttime gay lifestyle,” said Joel Smith, the Morgan’s curator of photography, in 2017. “It was easy for the mainstream culture to think of him as ‘the other one,’ or ‘the minor one.’ He did not have Mapplethorpe’s knack of promoting himself.”

Fran Lebowitz [at Home in Morristown] (1974)

Hujar had a complicated relationship with his own fame, which his friend and confidant Lebowitz knew intimately. “Peter Hujar has hung up on every important photography dealer in the Western world,” she said at his funeral. In interviews, she recounted his reluctance to play by the rules of the art world—once, he even threatened to break a barstool over an art dealer’s head.

Lebowitz—who is known for her dry, witty writing on American life and her three-decades-long writer’s block—also reclined in bed for Hujar. In 1974, the photographer took a portrait of Lebowitz in her home in Morristown, New Jersey. In the frame, the writer is nude under her blankets and propped up on her elbows on polka-dotted sheets, her gaze steadfast on the camera. “I hate having my photo taken, and none of the times that Peter took my picture was it an arduous experience,” she said in 2016 during a talk at Kasmin Gallery. She didn’t even recall the events leading up to the portrait in her home and added: “Until a year or two ago, I didn’t know that it existed.”

![Jay and Fernando [Two Men in Leather Kissing]](https://d7hftxdivxxvm.cloudfront.net/?resize_to=width&src=https%3A%2F%2Fd32dm0rphc51dk.cloudfront.net%2FLHog2_Ycbv17uZMnmymZjA%2Flarger.jpg&width=1200&quality=80)

![Fran Lebowitz [at Home in Morristown]](https://d7hftxdivxxvm.cloudfront.net/?resize_to=width&src=https%3A%2F%2Fd32dm0rphc51dk.cloudfront.net%2FT227cmm0TGEcfqwhKDZM8Q%2Flarger.jpg&width=1200&quality=80)

No comments:

Post a Comment