|

| Egon Schiele, Mujer sentada con la pierna doblada, 1917 Národni Galarie, Praga. |

Klimt / Schiele review – their obsessions were mutual

Royal Academy, London

Ferociously brilliant young Egon Schiele and established master Gustav Klimt share the spotlight in this compelling Viennese double bill

Laura Cumming

Sunday 4 November 2018

Egon Schiele drew Gustav Klimt many times in life, but also in death. Three drawings exist of Klimt in the morgue, his handsome face deformed by a massive stroke at the age of 55. Not many months later, Schiele himself was carried off by Spanish flu in the space of three devastating days. He was 28. Both men died in Vienna in the year 1918.

Death steals like a cold breath through the Royal Academy’s centennial commemoration of their art. It is there in the gaunt faces of Klimt’s old women and his syphilitic femme fatales. It is there in the emaciated bodies of Schiele’s teenage prostitutes, prematurely aged, and in the bony fingers that clutch at the bare ribs of his female nudes. It is the look of an era, of a society cursed by decadence and poverty, hunger, disease and war. But it is also art nouveau in late-stage mutation, an aesthetic of nervous whiplash lines and extraordinarily adroit drawings where a whole human being may be summarised in a few incisive curves.

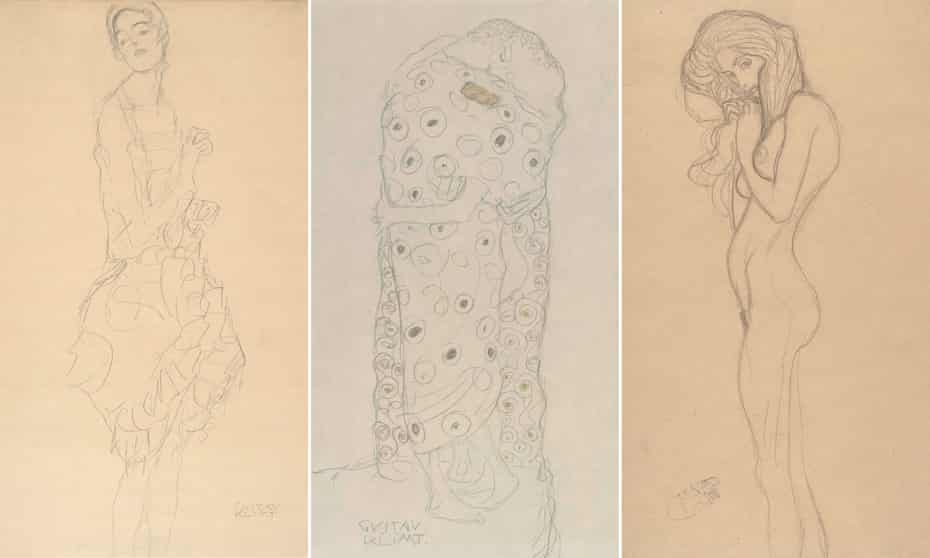

Klimt was an established star and Schiele a cocksure student when the two first met in 1908. But it is immediately obvious from this show that their obsessions were already mutual. Figures partially clothed or flagrantly exposed, subject to erotic rapture or isolation, entwined in almost unreadably elaborate embraces or laid bare on the ground (and the page): all are drawn with an extreme linearity characterised by gracefulness in Klimt’s case, or by Schiele’s fierce and burning clarity.

At first this show appears to emphasise what they share. Klimt draws people as lithe shapes, his sumptuous line reducing all the troublesome complexities of limbs, muscle and flesh, let alone inner being, to a sequence of contours. Schiele takes the contours and makes them harsh, sharp and angular. Klimt’s figures are radically cropped; his lean and sinuous nudes, looking like Kate Moss with big hair, are often cut off at the arms or knees, as if they were standing in water. Schiele goes even further, describing an entire arm with little more than the creased sleeve at the elbow. His wife is a floating face, ink-drawn and cupped in a fine sliver of hand, but so concise that the mind’s eye turns it into a complete portrait.

But the contrasts between the two artists soon become apparent. Klimt’s line is all rhythmic flow, sweeping softly around the anatomy, rounding out the sharp angles of pelvis, rib or shoulder blade. Klimt doesn’t just skim, he euphemises. This is partly because his drawings are almost invariably studies for full-scale paintings, armatures for those extravagant pile-ups of gold and high-chrome pattern. It is quite strange to see his figures stripped of the glitz, in isolation on the page, resembling faint pencil ghosts.

Klimt’s drawings of Viennese bankers and socialites are strikingly faceless, presumably for the same reason. They will only come into being as portraits in oil. And the sketches of his elderly mother establish only the most cursory likeness because she is posing for the figure of age in some extravagantly over-produced allegory. Klimt’s paintings are not born of spontaneous, rapid or natural observation, some of the virtues generally associated with drawing. Whereas for Schiele, with all his prodigious graphic gifts, drawing – and indeed each and every drawing – is an end in itself.

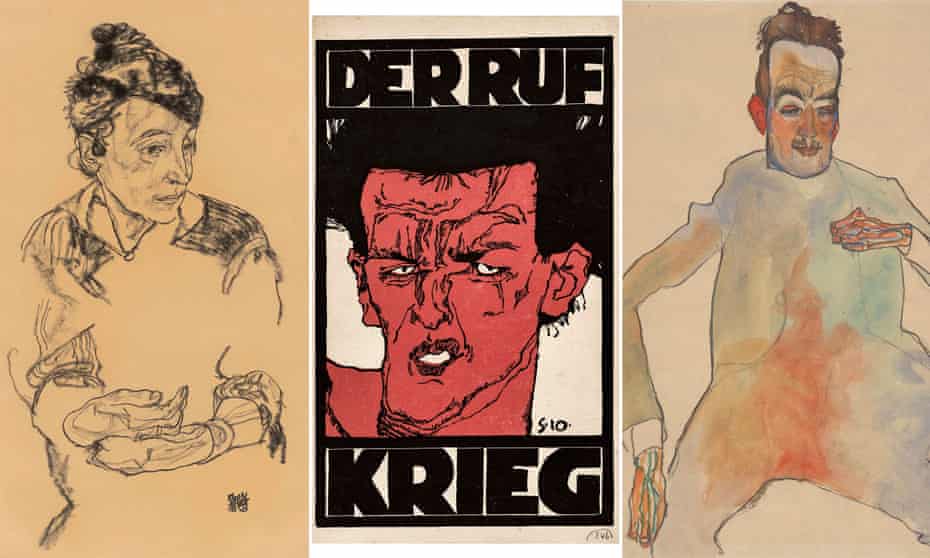

It is marvellous to see what Schiele learns from Klimt: all that concision, and editing, taken to electrifying extremes. Here is a terrific red head (in both respects) of the artist Max Kahrer, his beard crackling, the hair practically alight. The drawing is in profile, the eye brilliantly indicated with a single dash and yet you would know him anywhere, a belief confirmed by a front-on sketch of Kahrer two galleries later. And where Mrs Klimt is a type, Schiele’s mother, Marie, is patient, wistful, gently self-conscious in a poignant sketch in black chalk made not long before her son’s death.

Schiele draws a cellist playing music, his invisible instrument brilliantly implied by the splayed knees and the bowing, plucking gestures of the delicate hands. Body hair is a fine squiggle, speeding or slowing according to its origin in the arm pit or chest. His graphic notations are so superb that the hue and colour of a girl’s eyes – pale green, as it seems – are entirely communicated through the elliptic spirals controlled by his pencil.

And his own face, grimacing beneath its famous shock of hair, turns red with rage on the cover of The Call magazine at the prospect of war across Europe in 1912. The Royal Academy has stunning self-portraits from each year of Schiele’s single-decade career. These include the great and startling Self-Portrait With Eyelid Pulled Down, which looks as if it was drawn in blood. Much less familiar is a watercolour sketch made in prison, when the artist was awaiting trial on false charges of kidnap and indecency. He lies tormented on the bed: face a rictus of suffering, body a frail grey balloon.

Klimt never drew his own face. He had, he said, no interest in his inner self. And a curious lesson of this enthralling exhibition is that Schiele, who left so many portraits of himself as martyr and victim, doesn’t single himself out in this respect. Numerous drawings show the skull beneath the skin, the poor, bare, forked animal as a fragile contraption held together by pulleys and wires, subservient to the forces of sex and death. Although both artists produced unexpurgated images of men and women masturbating, or in full intercourse, only Klimt’s drawings were bound in leather for the delectation of the gentleman customer. Schiele’s scenes always feel far more stricken than erotic.

And it is this kind of comparison that makes the show so compelling. It could hardly be a definitive account of their respective drawings, since all the loans come from one museum – the magnificent Albertina in Vienna. But the judicious selection and extremely intelligent interleaving of images by theme, time and place brings into unusually close focus not only the art of these two great Viennese modernists, but the nature of drawing itself. Klimt so silky and so luxuriously addicted to the human form, almost whispering it into shape; Schiele so quick to the body immediately before him in the room, his lines so agile and potent – the distance between one kind of drawing and another is all there, measured even in the different pressures of a pencil point.

No comments:

Post a Comment