|

| Harry Dean Stanton |

Harry Dean Stanton: 'Life? It's one big phantasmagoria'

The wine, the women, the song… The great Harry Dean Stanton talks to Sean O'Hagan about jogging with Dylan, Rebecca de Mornay leaving him for Tom Cruise and why Paris, Texas is his greatest film

Sean O'Hagan

Saturday 23 November 2013 20.00 GMT

H

arry Dean Stanton is singing "The Rose of Tralee". His wavering voice echoes across the rows of people gathered in the Village East cinema in New York, where a special screening of a new documentary about his life and work, Partly Fiction, has just finished. You can tell that the director, Sophie Huber, and the cinematographer, Seamus McGarvey, who are sitting beside him, are used to this sort of thing from Harry, but the rest of us are by turns delighted and a little bit nervous on his behalf. Now that he's 87, Stanton's voice is as unsteady as his gait, but he steers the old Irish ballad home in his inimitable manner and the audience responds with cheers and applause.

"Singing and acting are actually very similar things," says Stanton when I ask him about his other talent, having seen him perform about 15 years ago with his Tex-Mex band in the Mint Bar in Los Angeles. "Anyone can sing and anyone can be a film actor. All you have to do is learn. I learned to sing when I was a child. I had a babysitter named Thelma. She was 18, I was six, and I was in love with her. I used to sing her an old Jimmie Rodgers song, 'T for Thelma'." Closing his eyes, he breaks into song: "T for Texas, T for Tennessee, T for Thelma, that girl made a wreck out of me." He smiles his sad smile. "I was singing the blues when I was six. Kind of sad, eh?"

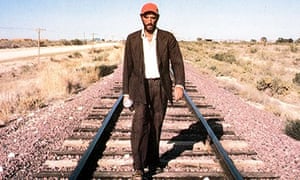

There is indeed a peculiar kind of sadness about Harry Dean Stanton, a mix of vulnerability, honesty and seeming guilelessness that has lit up the screen in his greatest performances. It's there in his singing cameo in 1967's prison movie Cool Hand Luke, in his leading role in Alex Cox's underrated cult classic Repo Man in 1984 and, most unforgettably, in his almost silent portrayal of Travis, a man broken by unrequited love in Wim Wenders's classic, Paris, Texas. "After all these years, I finally got the part I wanted to play," Stanton once said of that late breakthrough role. "If I never did another film after Paris, Texas I'd be happy."

Now, with mortality beckoning, Stanton still gives off the air of someone who, as he puts it, "doesn't really give a damn". In his room in a hip hotel on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the aircon is on full blast despite his runny nose and troubling cough, and he smokes like a train as if oblivious to the law and the health police. He looks scarecrow thin, but dapper, in his western suit, embroidered shirt and ornately embossed cowboy boots: a southern dandy even in old age. His hearing is not so good, but his voice remains unmistakable, that soft trace of his southern upbringing in rural Kentucky still detectable. "I've worked with some of the best of them," he says. "Not just directors like Sam Peckinpah and David Lynch, but writers like Sam Shepard and singers like Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson. I could have made it as a singer, but I went with acting, surrendered to it, in a way."

Before Paris, Texas, Stanton had appeared in around 100 films and since then he has acted in more than 50 more, though often as a supporting actor. The lead roles did not materialise in the way he expected them to, perhaps because he is so singular, both in looks and acting ability. When given the right script and a sympathetic director, though, he is as charismatic as anyone, as his role in David Lynch's The Straight Story showed. Recently he has shone fitfully in Martin McDonagh's Seven Psychopaths, and in the HBO series Big Love as a self-proclaimed Mormon prophet. He has also appeared in action pics such as The Last Stand with Arnie Schwarzenegger and in the Marvel blockbuster Avengers Assemble. He appears not to care too much about the kind of fame and huge earning power that other actors without an iota of his onscreen presence command.

"Harry is a walking contradiction," says Huber, who has known him for 20 years. "He has this pride in appearing to not have to work hard to be good. He definitely does not want to be seen to be trying. It's part of his whole Buddhist thing." His worldview is a mixture of various Buddhist and other more esoteric eastern philosophies, shaped in the late 60s by the writings of Alan Watts, the Beat poet and Zen sage, and adapted over the years to suit Stanton's singular, slightly eccentric lifestyle.

"Harry is a walking contradiction," says Huber, who has known him for 20 years. "He has this pride in appearing to not have to work hard to be good. He definitely does not want to be seen to be trying. It's part of his whole Buddhist thing." His worldview is a mixture of various Buddhist and other more esoteric eastern philosophies, shaped in the late 60s by the writings of Alan Watts, the Beat poet and Zen sage, and adapted over the years to suit Stanton's singular, slightly eccentric lifestyle.

Lately, though, at screenings of Huber's documentary, he has reacted angrily to Wim Wenders's onscreen observation that Stanton was insecure about playing the lead role in Paris, Texas. "I asked him: 'Harry, how come you are angry at that scene? I thought you didn't have an ego,'" says Huber. "He just nodded and said: 'Yeah, I guess I should shut up.' But it had obviously got to him."

Stanton tells me more than once that he has no ego and no regrets, but you have to wonder if that is true. He is, as Partly Fiction shows, a kind of lone drifter in Hollywood, perhaps the last of that generation of great American postwar character actors, and certainly one of the most singular.

Back in the late 60s, he shared a house in Hollywood with Jack Nicholson, and they partied hard with the David Crosby, Mama Cass Elliot and the burgeoning Laurel Canyon rock aristocracy of the time. Now, still an unrepentant bachelor, he speaks fondly on camera about the great lost love of his life, the actor Rebecca de Mornay – "She left me for Tom Cruise."

When a wag in the audience asks him what Debbie Harry was like "in the sack", he shoots back: "As good as you think!" adding that the Nastassja Kinski was pretty good, too.

Stanton spends most evenings, when he is not working in Dan Tana's bar in East Hollywood, drinking with a small bunch of regulars and telling anyone who can't quite place his face that he is a retired astronaut. "He's an outsider but has lots of good friends," says Huber. "He's happy compared to most 87-year-olds. He says he doesn't care about dying, but some days, I suspect, he thinks about it a lot. You never really know what's going on in his head."

Stanton spends most evenings, when he is not working in Dan Tana's bar in East Hollywood, drinking with a small bunch of regulars and telling anyone who can't quite place his face that he is a retired astronaut. "He's an outsider but has lots of good friends," says Huber. "He's happy compared to most 87-year-olds. He says he doesn't care about dying, but some days, I suspect, he thinks about it a lot. You never really know what's going on in his head."

This is exactly how Stanton likes it, of course. In Huber's slow, almost meditative film, Stanton looms large while revealing little. The New York Times reviewer concluded: "You won't learn much, but you'll be strangely happy that you didn't." Stanton quotes the line back to me, grinning. "She got it," he says approvingly. "That's a very Buddhist thing to say."

Huber describes Partly Fiction as "a portrait of his face" and those expressive eyes and weathered features, shot close-up in black and white by McGarvey's luminous cinematography, do indeed speak volumes about how Stanton has made silence and stillness his most powerful means of onscreen communication. There is a great scene where David Lynch, his equal in eccentricity, talks about what Stanton does "in between the lines" and how he is "always there – whatever 'there' needs to be".

Stanton smiles when I mention it. "I guess he was talking about being still and listening. Being attentive even when it's not your line. For me, acting is not too different from what we are doing right now. We're acting in a way, but we are not putting on an act. That's the crucial difference for me. I just surrender to it in much the same way I surrender to life. It's all one big phantasmagoria anyway. In the end I've really got nothing to do with it. It just happens, and there's no answer to it."

In all kinds of ways, Stanton has travelled lunar miles from his smalltown upbringing in East Irvine, Kentucky. Born in 1926, he is the eldest of three sons to Ersel, who worked as a hairdresser, and Sheridan, a tobacco farmer and Baptist. Stanton describes his childhood as strict and unhappy. "My father and mother were not that compatible. She was the eldest of nine children and she just wanted to get out. I don't think they had a good wedding night, and I was the product of that. We weren't close. I think she resented me when I was a kid. She even told me once how she used to frighten me when I was in the cradle with a black sock."

He laughs soundlessly but looks unbearably sad. "I brought all that stuff up with her just after I started seeing a psychiatrist. I did group therapy and all that and it all came out. So I called her one night and told her I hated her." He shakes his head and smiles ruefully. "We made up shortly before she died. Got pretty close then, actually. That's how it goes sometimes."

He laughs soundlessly but looks unbearably sad. "I brought all that stuff up with her just after I started seeing a psychiatrist. I did group therapy and all that and it all came out. So I called her one night and told her I hated her." He shakes his head and smiles ruefully. "We made up shortly before she died. Got pretty close then, actually. That's how it goes sometimes."

Was acting in some way an attempt to escape that grim childhood?

"Yes, I guess so. You can do stuff onstage that you can't do offstage. You can be angry as hell and enraged and get away with it onstage, but not off. I had a lot of rage for a time, but I let go of all that stuff a long time ago."

Stanton served in the US Navy during the Second World War, working as a ship's cook. "Most actors don't have that kind of life experience now," he says matter-of-factly. "I was lucky not to have been blown up or killed. I was there when the Japanese suicide planes were coming in. Fortunately they missed our boat. Took me a while to readjust after I went back home and went to college in Lexington, Kentucky." There he started acting in the college drama group while studying journalism. "I acted in Pygmalion with a Cockney accent. I knew right then what I wanted to do, so I quit college and went to the Pasadena Playhouse in 1949."

He landed his first job after answering a "singers wanted" advert in the local paper and toured for a while with a 24-piece choral group. "Twenty-four guys on a bus playing small towns. When I quit, there were only 12 guys left. The rest deserted along the way. We sang on street corners, in department stores and, at the end of a week, in a local venue. It's called paying your dues."

The dues-paying continued with myriad supporting roles on television in the 1950s, including appearances in popular western series such as Wagon Train and Gunsmoke. In 1967 he had a brief, but resonant, role as a guitar-strumming convict in Cool Hand Luke, starring Paul Newman. By the early 1970s, he had become a cult actor courtesy of two indie classics directed by the mercurial Monte Hellman: Two-Lane Blacktop and Cockfigher. In the former he befriended the singer James Taylor, who wrote a song, "Hey Mister, That's Me Up On The Jukebox", on Harry's favourite guitar. He later befriended Bob Dylan during the famously difficult shoot for Sam Peckinpah's elegiac western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in 1973. "Dylan and I got to be very close. We recorded together one time. It was a Mexican song. He offered me a copy of the tape and I said no. Shot myself in the foot. It's never seen the light of day. I'd sure love to hear it."

In Partly Fiction (which has yet to get a UK release date), Kris Kristofferson, who played the lead in that film, recalls Peckinpah throwing a knife in anger at Stanton when the actor messed up a crucial scene by running through the shot. "As I recall, he pulled a gun on me, too. It was because me and Dylan fucked up the shot."

In Partly Fiction (which has yet to get a UK release date), Kris Kristofferson, who played the lead in that film, recalls Peckinpah throwing a knife in anger at Stanton when the actor messed up a crucial scene by running through the shot. "As I recall, he pulled a gun on me, too. It was because me and Dylan fucked up the shot."

On purpose? "No, we were jogging and we ran right across the background." The vision of Dylan and Stanton jogging together seems altogether too absurd, but I let it pass. He describes Peckinpah as "a fucking nut, but a very talented nut". Likewise the maverick British director Alex Cox, who cast him in Repo Man in 1984. "He was another nut. Brilliantly talented and a great satirist, but an egomaniac."

That same year, Stanton made Paris, Texas, and created his most iconic role. "It's my favourite film that I was in. Great directing by Wenders, great writing by Sam Shepard, great cinematography by Robby Müller, great music by Ry Cooder. That film means a lot to a lot of people. One guy I met said he and his brother had been estranged for years and it got them back together."

Does he think he should have had bigger, better roles in the years since? He lights up another cigarette and stares into the middle distance, lost in some private reverie. "You get older," he says finally. "In the end, you end up accepting everything in your life – suffering, horror, love, loss, hate – all of it. It's all a movie anyway."

He closes his eyes and recites a few lines from Macbeth, sounding suddenly Shakespearean, albeit in his own wavering way. "A tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing." He opens his eyes again. "Great line, eh?" he says, smiling and reaching for a cigarette. "That's life right there."

No comments:

Post a Comment