Book of the month: Juan Marsé

Anne Morgan

September 30, 2019

I love meeting translators. Having built their careers around enabling people to access the work of other writers – lending readers their eyes, as I describe it in my book Reading the World – they are often very generous, knowledgeable and fascinating.

Nick Caistor is a case in point. With a string of famous works to his name, including novels by Paulo Coehlo, José Saramago and Dominique Sylvain, this three-time Premio-Valle-Inclán-winner and former BBC World Service Latin America editor is a mine of insights and stories. When I met him to record a (yet-to-be-released) podcast for the Royal Literary Fund this month, we had a wonderful discussion about the frustrations and joys of helping literature to travel, topped off by a delicious lunch from a Brazilian stall on the street market near his London flat.

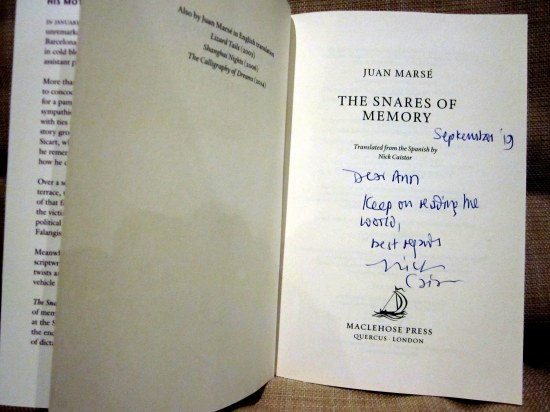

Caistor’s kindness didn’t end there. A few days later, a package dropped onto my doormat: his recent translation of Spanish Cervantes prize-winner Juan Marsé’s Esa puta tan distinguida (or The Snares of Memory, as Caistor has rendered it in English).

The premise is intriguing. In 1980s Barcelona, a writer is hired to create a film script based around the murder of a prostitute in a cinema projection booth more than thirty years before. In his efforts to achieve authenticity, the writer seeks out the convicted murderer, one Fermín Sicart, and, over the course of a series of taped discussions, attempts to get to the bottom of the crime. There is a problem, however. Though Sicart accepts his guilt, he cannot recall why he killed his victim. As the writer tries to grope his way towards an understanding of his subject, he is forced to interrogate his own motives and methods for translating this gruesome episode to the silver screen.

The book is surprisingly funny. Helped along by abrupt shifts in register that reliably undercut the writer’s loftier reflections, a strong current of bathos and formidable housekeeper Felisa, who has no compunction about interrupting the narrator’s work to harangue him about his unhealthy habits, offer her opinions or subject him to another of her ‘riddles’ taken from classic films, the narrative is extremely entertaining.

This is nowhere more true than during the passages in which the writer reflects on the difficulties and compromises of the creative process. For a fellow novelist, the section describing five hours spent crossing out sentences in a handful of barely legible pages is particularly enjoyable (not to say reassuring!). There is also a lot of fun in the passages that skewer the Spanish film industry. Beholden to politics and funding issues, the project lurches from one director and producer to another, morphing dramatically with each shift so that the writer is constantly obliged to reframe his vision in light of considerations that have nothing to do with the quality of the work.

The humour in no way detracts from the rigour and beauty of the prose, however. Indeed, Marsé and Caistor’s descriptions of writing and the mechanisms of self-censorship are among the most memorable I’ve read. In showing how ‘the story came to me from an undeniable personal tragedy, but was also rooted in the fraught memory of the dark days of the dictatorship, the resentment, humiliation, pain and desire for revenge that still persisted in many different guises in the collective subconscious’, the narrative makes the particular universal – one of the hallmarks of great literature.

Rather than getting in the way, the human elements of the story – the writer’s fretting about money, Sicart’s flashes of forgetfulness, and Felisa’s complaints about clearing up cigarette butts – elevate the work. They imbue the novel with life, allowing us to experience the emotional reality of the ideas it explores rather than simply presenting them on the page, while the intrigue of the plot draws us on.

‘Haven’t I told you a thousand times that the black or noir novel as they call it in French is the best way to investigate social conflicts, explore the human condition, to denounce implacably the injustices and corruption of our society?’ remarks an incidental character in a doctor’s waiting room midway through the book. In Marsé’s hands, this is certainly true.

The Snares of Memory (Esa puta tan distinguida) by Juan Marsé, translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor (MacLehose Press, 2019)

I'm Ann Morgan, a UK-based author, TED speaker, Royal Literary Fund fellow and editor. My first book, 'Reading the World' or 'The World Between Two Covers', as it's known in the US, was inspired by my year-long journey through a book from every country in the world, which I recorded on this blog. I'm also the author of two novels: 'Beside Myself' and 'Crossing Over'.

I'm Ann Morgan, a UK-based author, TED speaker, Royal Literary Fund fellow and editor. My first book, 'Reading the World' or 'The World Between Two Covers', as it's known in the US, was inspired by my year-long journey through a book from every country in the world, which I recorded on this blog. I'm also the author of two novels: 'Beside Myself' and 'Crossing Over'.

No comments:

Post a Comment