When Gabriel García Márquez wanted to be a foreign correspondent in Madrid

English version by Asia London Paloma

J.A. Aunion

Bogotá, 26 April 2019

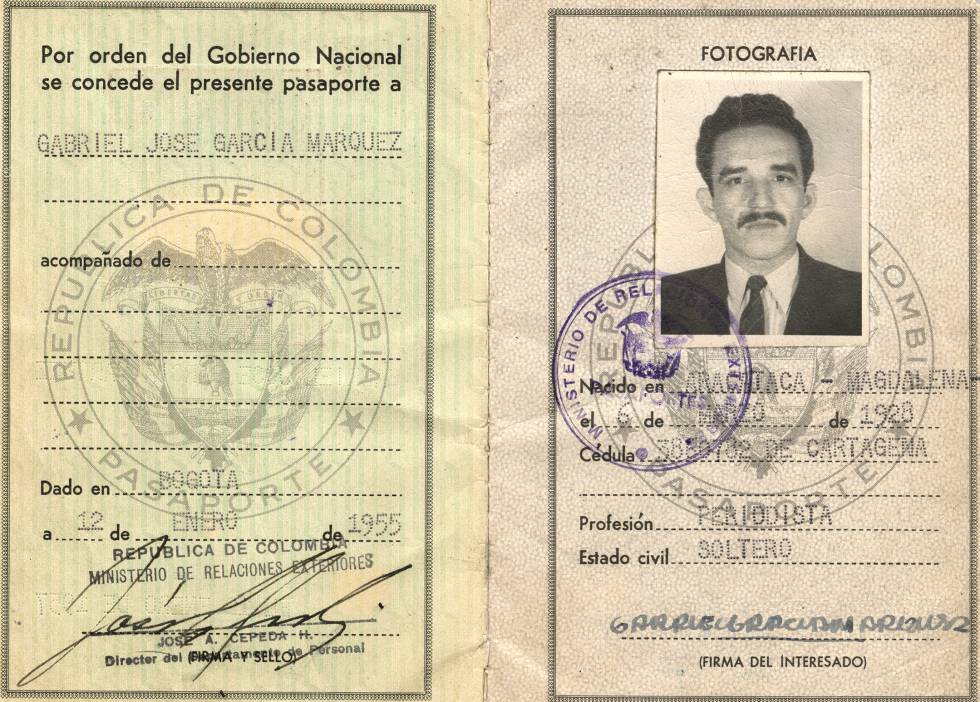

When the young journalist Gabriel García Márquez was forced to leave Colombia in 1955 – he had upset the government of dictator Rojas Pinilla with a series of articles linking smuggling to a boat accident that involved members of the military – he was forced to live in exile in Europe, wandering through cities such as Geneva, Rome and Paris, according to his biographer Dasso Saldívar.

It appears that García Márquez could have established himself professionally in Madrid

ÁLVARO SANTANA ACUÑA, RESEARCHER AT WHITMAN COLLEGE

In 1955, a young García Márquez also traveled to Madrid, which at the time was the capital of the Francisco Franco dictatorship, and asked El Espectador, a newspaper in the Colombian capital Bogotá, if he could remain as a foreign correspondent.

“It was one of the ideas he proposed to his bosses in Colombia at that time. It’s still a little unclear and needs to be studied more, but it appears that García Márquez could have established himself professionally in Madrid,” explains Álvaro Santana Acuña, a researcher at the Whitman College in Washington.

Acuña is referring to a letter written by the Colombian author in 1955, which has been conserved by the Harry Ransom Center of Humanities at the University of Texas, in Austin. Acuña found the letter after studying the years-long correspondence between García Márquez and Guillermo Cano, the editor of El Espectador, who was assassinated by Pablo Escobar’s hitmen in 1986. “García Márquez was in Madrid and asked Cano for a column on Spanish issues, for example an article on [Spanish writer] Pío Baroja,” says Acuña.

The letters García Márquez sent to Cano were acquired by the Harry Ransom Center at the end of 2018 in a bid to expand its already extensive archive on the author, who was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1927, and died in Mexico four years ago in April 2014.

García Márquez’s personal files include 78 boxes of documents, 43 photo albums and 22 notebooks

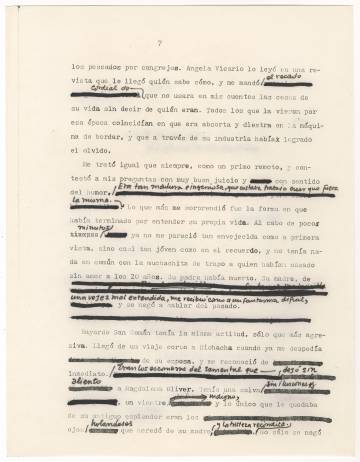

The correspondence with Cano provides information about a little-known time in the writer’s life, for instance his economic hardships in Paris and the feature articles he wrote while in Eastern Europe. “He considered some of them, those on life in communist countries, to be his best work,” says Acuña. The correspondence also includes a letter in which García Márquez informs Cano that he is writing a novel called Cien Años de Soledad (or, One Hundred Years of Solitude). The letter includes a small excerpt from the book that was published in El Espectador in 1966. “In the letter, he recognizes that it is the first time in his life that he’s published a fragment of a novel that hasn’t been published yet. He does this following the trend set by some of the greatest authors of the era, such as Carlos Fuentes or Mario Vargas Llosa.”

This decision to publish excerpts is fundamental to understanding how García Márquez became a professional writer – a subject that is the focus of a book Acuña will publish next year, and which is based on his research at the Harry Ransom Center. Since 2014, the center’s archive has included García Márquez’s personal files: 78 boxes of documents, 43 photo albums and 22 notebooks and notes, which have been partially digitized and are open to public consultation. These documents allow Acuña to “reconstruct the process in which García Márquez passes from a talented Colombian writer to a Latin American and global author,” he says.

García Márquez actively sought out the opinion of friends, colleagues and critics including Colombian poet Álvaro Mutis, Spanish actress María Luisa Elío and her filmmaker husband Jomi García Ascot, critic Emmanuel Carballo and writer Carlos Fuentes, to whom he sent the first 80 pages of Cien Años de Soledad. From the first chapter published in El Espectador in May 1966 to the final edition released in 1967, “42 significant changes” were made to the iconic novel.

Unpublished documents

The writer’s eager search for feedback will also be explored at an exhibition called “Gabriel García Márquez, the creation of a global author,” which is directed and curated by Acuña, and will open next year at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. The exhibition will feature “unpublished and little-known documents,” says Acuña, who explains there will be a section on the author’s life, another on the creation of Cien Años de Soledad and its impact, an area focused on his political activism, and another on his other works like El amor en los tiempos del cólera (or, Love in the Time of Cholera) and Crónica de una muerte anunciada (or, Chronicle of a Death Foretold).

Another part of the exhibition will look at his influence on writers across the world, including Toni Morrison and Haruki Murakami, and the authors who influenced him. “In the Harry Ransom Center there are documents that we will be able to show from, for example, James Joyce, Jorge Luis Borges and William Faulkner,” explains Acuña.

The exhibition is set to open in the first week of February 2020, and will remain at the center in Austin until June. The organizers are already in talks with museums in Mexico about showing the exhibit there at the beginning of the summer.

No comments:

Post a Comment