|

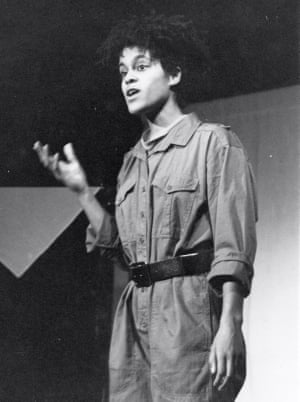

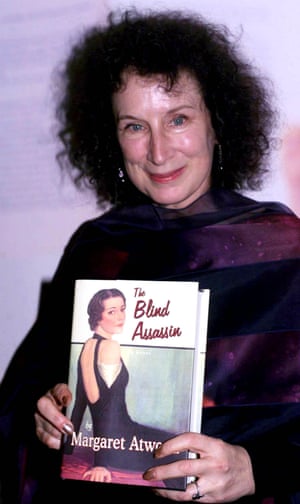

| Bernardine Evaristo and Margaret Atwood Photograph: Graeme Robertson/The Guardian |

Booker winners Bernardine Evaristo and Margaret Atwood on breaking the rules

The judges staged a ‘joyful mutiny’ to name the pair joint winners of the literary prize. And that’s not all that unites them

by Claire Armitstead

15 October 2019

It was clear that things were not going to plan when, just half an hour before the guests began to arrive, the judges of this year’s Booker prize had yet to make a decision. Five hours after they had begun their deliberations, they finally emerged in a state of “joyful mutiny” to announce that they had decided to break with convention, throw out the rule book and anoint two winners rather than the usual one.

By happy coincidence, Bernardine Evaristo is the same age that Margaret Atwood was when, in 2000, she first won the Booker prize with The Blind Assassin. “And I’m happy that we’ve both got curly hair,” quipped Atwood as they took to the stage arm in arm. They talk about it again the following morning, comparing notes about hair etiquette and handy products for curls. “People used to review my hair back in the day,” says Atwood.

At first glance, the two prizewinning novels seem worlds apart. Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other is a polyphonic look at the lives of 12 black British women that spans the past 100 years, while Atwood’s The Testaments plunges us back into Gilead, the totalitarian state she created in 1985, when Evaristo was a radical lesbian theatremaker still in her 20s. Did the younger woman read The Handmaid’s Tale when it first came out?

“Obviously I knew about it, because lots of women around me had read it,” says Evaristo, “but I didn’t read it until the late 90s because I was reading African American women in my 20s, as they were the ones who I needed to read: Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde. They’re the ones who spoke to me. But when I did read it, I just thought it was a fantastic, chilling story. And so powerfully feminist.”

Both winning novels continue that feminist tradition, though both could also be seen to contain critiques of it. In The Testaments, as in The Handmaid’s Tale, women are oppressed by women – notably the scary Aunt Lydia – while in Girl, Woman, Other, the teenage Yazz dismisses her mother as a feminazi: “To be honest, even being a woman is passé these days,” she sneers.

Both authors laugh: “So, yeah, she’s a teenager,” says Evaristo. “Of course she has to counter the mom,” agrees Atwood. “And, in fact, the same thing happened in The Handmaid’s Tale back in 1985. Offred has this feminist mom of the 60s and 70s who she considers really extreme and passé, and her mother keeps saying: ‘Just you wait.’”

Yazz’s mother is Amma, who is a theatremaker, as Evaristo once was. We meet the character on the eve of her big success – a premiere of her play The Last Amazon of Dahomey, at the National Theatre – but the novel traces her back to a 1980s London of squats and lesbian collectives. How autobiographical is it all?

“She’s a version of my younger self,” confirms Evaristo. “I wanted to write about that 1980s era of, particularly, black women feminists who were creating art together, who felt like outsiders in society and who were very brave and also very confrontational – you know, because that was a very confrontational era. I used to heckle; Amma heckles. And Amma is lesbian. And I was lesbian in the 80s.

“A lot of the women creating theatre and art and dance and so on were lesbian or bisexual and working in a quite segregated way, but feeling empowered by each other – not having to explain themselves to other people, not feeling that they needed to bring men in. Then, I think, a lot of people reach a stage where they no longer need that; and also sexuality changes; my own sexuality changed.”

Evaristo was the fourth of eight children born to an English mother and a Nigerian father in south-east London in 1959. Although Atwood grew up in Canada 20 years earlier and spent her early childhood running wild during field trips with her entomologist father, there are similarities in their upbringings, not least in the traditional attitudes to gender in schools. “In the 50s and early 60s, girls took home economics, boys took woodwork and never the twain would meet,” says Atwood. “That’s the education I had. But, since I grew up in the woods and had a tomboy mother, who was not interested in those things at all, it didn’t take on me.” Evaristo says: “I went to a girls grammar school and did domestic science, and my brothers did woodwork or whatever they called it.”

Both women grew up in the heydey of the nuclear family, and their novels are an examination of less conventional families. “I have a gay man and a gay woman who raise a child separately; they’re not living together. I wanted to present a sort of queer family,” says Evaristo. “Amma has a support network around her; she chooses lots of people to be godparents so that she always has babysitters, for example.

“But,” she adds, “in the black British community, there is a bit of an issue with single-parent families – women raising children on their own. I do have one woman in the book who is raising her children on her own because her man is going off. But I also have some nuclear families.”

The nuclear family, Atwood chips in, was part of the burden of the 20th century. “In the 19th century, families were very extended. And then it became nuclear, which was actually very hard on women because they were expected to be in this house all by themselves with their Hoover and their washing machine. And that was supposed to be enough, but it meant that they didn’t have any support.

“So I think extended families and families that you make, rather than those you are handed on a plate, give people much more support. And, for instance, if you go to indigenous society, you will find a lot more generational support. So, grandmothers and elders are pretty important.”

Which brings us to the role of older women in the novels. Aunt Lydia could hardly be described as a positive role model, Atwood agrees, “but all occupying forces raise a contingent from within the people being oppressed to do the controlling, because it’s more effective and a lot cheaper. So of course they would raise a contingent of women. And so it has been throughout colonial history. As I say, nothing went into the book that didn’t have precedent in real life. Somebody reading the original Handmaid’s Tale once said: ‘This book was just like my girls school.’ Well, that’s nuns, you know …”

In Evaristo’s world, three of the strongest and most endearing women are elderly. “I really wanted to write an intergenerational novel, and to have women at every stage in their lives. I wanted them all to have their faculties intact and to be, to a certain extent, enjoying their lives and enjoying their independence.

“Older women don’t really feature much in fiction, which is such a shame, because we’re actually much more interesting than younger women, because we’ve lived full lives. But when young women write older women, they’re usually mad!”

Atwood nods. “When I went to the US right after the Trump election, these younger women were saying: ‘This is the worst thing that’s ever happened.’ No, it’s not. It’s not. Many worse things have happened.

“I also say that if your heart is broken when you’re 18, by 28, you’ve got some perspective; at 38, you’ll probably think it’s funny. And when you’re my age, you cannot remember who it was who broke your heart.”

Atwood nods. “When I went to the US right after the Trump election, these younger women were saying: ‘This is the worst thing that’s ever happened.’ No, it’s not. It’s not. Many worse things have happened.

“I also say that if your heart is broken when you’re 18, by 28, you’ve got some perspective; at 38, you’ll probably think it’s funny. And when you’re my age, you cannot remember who it was who broke your heart.”

Which brings both writers to their own ages. “Am I middle-aged now?” wonders Evaristo, who was at the Booker ceremony with her husband, whom she met on a dating site 13 years ago. “You know,” she ponders, “there’s this myth that old people don’t have energy. I think that if you look after yourself, you have energy.”

“Actually,” adds Atwood, “you often have more energy, because it isn’t going into the things it goes into when you’re younger such as” – she breaks into a loud stage whisper – “hormonal changes every month. There’s a middle period when you’re taking care of everybody – your kids, your parents – and you are really stretched. Then, as you get older, bad things happen, people die, but you are no longer caregiving to such an extent.”

Role models are key, says Evaristo. “It’s good for younger women to see older women who are leading fulfilled lives. I had a friend who was in her 90s who had been movement tutor at my drama school. And she was still teaching into her late 80s, working in Europe and running workshops. And she always had plans.

“It was so important for me to show that ageing is something to be welcomed and enjoyed. Because what can you do about it? I know that sounds really idealistic, but that’s what I try to tell myself, especially now that I’m 60.”

The forms that both women have chosen to express all these themes are also energetic. “Well,” says Atwood drily, “when you have totalitarianism, you’re going to have a lot of plot, because totalitarianism generates plots. And I don’t mean just the plot of the novel.”

Evaristo writes in a style which she calls “fusion fiction”. “I wanted to tell 12 women’s stories, so I had to find a form to fit that. It’s kind of patterned on the page, a bit like poetry, and there were very few full stops, but there are gaps between the lines that indicate some kind of breathing spaces. It allowed me to write each woman’s story in a way that was inside their heads and outside. And also to go back into the past and forward to the present.”

Although she has not written a play since the 80s, Evaristo acknowledges theatre’s influence on her work and says she is hoping to go back to it. When I wonder what influence the TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale has had on Atwood’s work, Evaristo points out that diversity quotas in casting have literally altered the complexion of Gilead. We also know that the TV series of The Handmaid’s Tale introduced the character of the missing baby Nicole, whose wherebouts is a central mystery in The Testaments.

Atwood doesn’t disagree: “There’s been a lot of discussion of the TV series, that they didn’t go the whole hog – because they would then have sent all the black people off to national homelands, as the South Africans did during apartheid. Perhaps North Dakota. I don’t know what you know about North Dakota, but it’s an inhospitable place to have a national homeland.”

Does television change the sort of stories that are told? “It changes the way stories are seen,” says Atwood. “It’s not like radio, where you can’t actually tell what colour the person is. If The Handmaid’s Tale were on radio, it wouldn’t work. You wouldn’t have all these protesters dressed as handmaids. It’s very visual.”

“Yeah,” says Evaristo, “I think, in terms of TV drama and stage drama cross-casting, as they call it, has been incredible. Especially recently. For example, Adjoa Andoh, a friend of mine, recently played Richard II at the Globe.”

|

| Sharing hope for the future: Evaristo and Atwood lock arms. Photograph: Graeme Robertson/The Guardian |

Both novels end on a note of optimism. Does this reflect the writers’ own attitudes. “What we think of as a family has changed,” says Atwood. “It’s been a big fight in in North America and especially for gay people. But we have gay marriage now.”

Evaristo shakes her head. “I think we’re in difficult political times. I normally have a very positive perspective on everything. But, at the moment, I find it very hard to have a positive perspective on the political climate in this country, let alone anywhere else.

“But with the characters I did not want to present 12 black women who are defeated by life, even though that is sometimes the case. So there is definitely hope in each of their narratives without it getting saccharine.”

Atwood agrees: “A pessimistic ending would be you kill everybody off. The ending of The Testaments is not optimistic for everybody in the story, but it does signal the beginning of the end. Or as Churchill said: ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’ Maybe the end of the beginning is optimistic enough under the circumstances.”

No comments:

Post a Comment