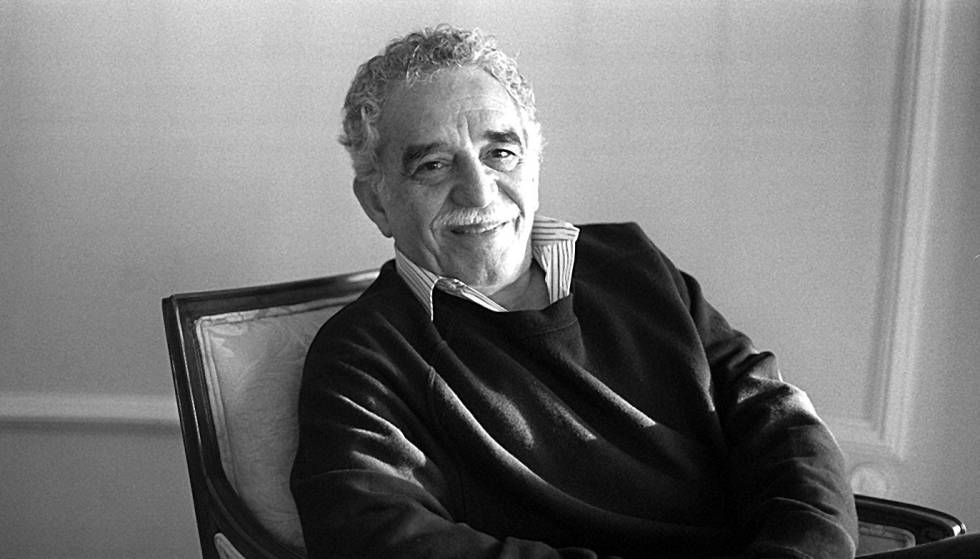

Gabriel García Márquez’s attention to detail, remembered 20 years on

Journalist who worked with the Nobel winner on ‘News of a Kidnapping’ recalls making of the book

English version by Heather Galloway

Bogotá, 30 September 2016

Darío Arizmendi, director of Caracol Radio’s morning show 6AM, got hold of Luzangela Arteaga, who was scarcely 30 years old at the time, hauled her out of the production studio and told her: “I am a great friend of Gabo, he’s working on something special, I don’t know what, but he asked me if I could find him someone who’s good on detail, who is reserved, someone special. I thought of you. You’re going to Cartagena tomorrow.”

Those two years with García Márquez were a lesson in journalism that Arteaga will never forget

Now 51, Arteaga recalls how she arrived in the Colombian coastal city, dialed the number Arizmendi had given her and went to Gabriel García Marquez’s “totally white” house. The person she encountered there was “very serious, analytical and entirely different from who he was subsequently.”

The writer asked Arteaga to follow him and they immediately sat down at a desk. “Look, this is what I’m working on,” he said before reading her a rough sketch of the first chapter of his next book, News of a Kidnapping, which was published 20 years ago.

For the next two years, Arteaga would shadow Márquez as he put together the powerful piece of non-fiction that would take him back to his journalistic roots.

Maruja Pachón and her husband Alberto Villamizar had suggested that García write a book about the former’s own kidnapping and six months of captivity two years earlier. The writer was working on the first draft when he realized that it made no sense if he didn’t link this experience to the other nine kidnappings that had taken place around the same time in Colombia, a country then plagued by drug cartels and by the drug lord Pablo Escobar.

This was where Arteaga came in. “That day at his house he told me about all the details he wanted to check,” she recalls. “As far as he was concerned, it was amazing that all the protagonists of something so frightening should open up and tell him about it.”

But that wasn’t enough. “He needed to give authenticity to what he was writing by confirming the minutest detail; he needed to know how cold it was, what traffic lights there were, how many bullets were fired – he wanted to know absolutely everything. That was my job for the next two years,” she says.

After endless interviews during which García Márquez made sure he squeezed all the details out of the interviewees, the author’s cousin and private secretary Margarita transcribed the hours of recordings. Afterwards, he met up with Arteaga: “A meeting with the maestro meant a task that would last another two months,” she says.

They sat down together to go over the notes on the transcriptions and to talk about the settings; about the details, always the details. It was in the detail that Arteaga recognized that Gabo’s greatness lay. “There was no room for doubt,” she recalls. “And if there was, we would pursue the matter until there wasn’t. If it wasn’t confirmed, it wouldn’t be included.”

Arteaga shadowed García Márquez as he put together the powerful piece of non-fiction

Gabo’s attention to detail was immeasurable. “He wanted to go to the cottage where they kept Maruja and Beatriz, he wanted to go into the bathroom… or get into the car that took them to the place where they joined Marina. As it says in the book, they had told him they could breathe and see out a little. He wanted to know how far they could see. I looked for that car for two years but it was impossible to find,” says Arteaga.

Although she laughs about it now, it was an exhausting job. “I worried constantly about imprecision and I took care that everything I showed him was backed up by a document,” she says, showing examples of the papers she has kept – newspaper and magazine cuttings, documents, rights of petition. Not all were needed. Some were collected merely out of curiosity, such as the summaries she had to do of the novels that the ex-vice president of Colombia, Pacho Santos, read during his period of captivity.

The working day was long and though it had a strict starting point, there was no end. As the book began to take shape and their relationship grew, Arteaga found herself increasingly on call, such as the Sunday she spent on the telephone from the time she was giving her daughters their lunch until night fell.

“He called from Mexico. He had been speaking to Beatriz and she had told him this detail about the perfume one of the kidnappers had given her and how he had called her ‘my love’. He was totally outraged. He felt what they told them intensely; it went so deep, he felt the same rage and frustration as them.”

During those two years, the young Arteaga couldn’t leak a word of what she was doing to his journalist colleagues, pretending instead that her insistent queries were simply the product of an inquiring mind.

A FEAST OF STORIES

A feast of stories for curious minds is the slogan for the fourth edition of the García Márquez awards organized by the author’s foundation and inspired by the Journalism Academy UAM/ El País. With the approach of the FARC peace deal referendum that will mark a turning point in Colombia’s tumultuous history, journalism will dominate the news in the country’s second-biggest city, Medellín.

Distinguished guest Martin Baron, editor of The Washington Post, will be talking about peace, music, literature and Latin American journalism. Celebrating its 40th anniversary, EL PAÍS will have its own stand where it will show the documentary it made on 23-F – Spain’s failed coup d’état – and also offer journalism workshops in the city’s schools.

Two decades have passed since then and Arteaga has been dusting off the documents she accumulated at that time, ready for a talk she will give on it in Medellín during the New Iberoamerican Journalism award ceremony organized by the Gabriel García Márquez Foundation. It will be a way of celebrating the 20thanniversary of the book that the author first read in front of a group of students at the EL PAÍS journalism academy in Madrid.

Those two years were a lesson in journalism that Arteaga will never forget. Just as she will never forget one of her last encounters with Gabo. Shortly after News of a Kidnapping was published, Darío Arizmendi knew that the author was about to catch a flight. “Go to the airport and get an interview,” he told Arteaga.

Arteaga arrived at the airport and greeted Gabo warmly.

- I’m not going to answer any more of your questions, laughed Márquez.

- At least you can’t blame me for trying, maestro.

-No, he said. I would have blamed you if you hadn’t.

No comments:

Post a Comment