|

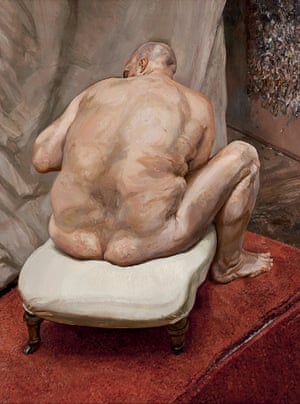

| Painting of Ria almost finished: Lucian Freud photographed in his studio with model Ria Kirby by his assistant, David Dawson, 2007. Photograph: © David Dawson |

‘I was Lucian Freud’s spare pair of eyes’

Former Observer art critic William Feaver was a friend of Lucian Freud for 30 years. As the first volume of his biography of the painter is published, he recalls their time together, and Freud’s journey from obscurity to global fame

William Feaver

Sunday 8 September 2019

The phone went. After midnight, so it could only be him. “Hello Villiam. How goes it?” That faintly Germanic tinge and, as always, straight to the point: “I’ve got her a dog.”

Alice, my youngest daughter, just 13, had been ill for some time and felt wretched. A whippet, Lucian knew (“Don’t you agree?”), would do her good, whippets being brisk yet graceful, affectionate enough – he disliked the slobbery characteristics of lesser breeds – and, he’d found, exemplary sleeper-sitters. Pluto, a whippet bitch bought some years before for Lucian’s daughter Bella, but soon adopted by him, had long been adored, not to say coveted, by Alice.

And so it was that a few weeks later we collected the elegantly piebald Meri from Jan in Dorset, who, long before becoming a premier whippet breeder, had been friendly with Elvis during his military service in West Germany. There were photos to prove it.

This dog-in-the-night incident was typical of Lucian: sure instinct coupled with exotic connections and sudden generosity. With him on the line, how blurred at any hour of day or night were the distinctions between personal and impersonal, between the private and the renowned.

I knew him for nearly 40 years and for 30 of these counted him as a friend. Yet I never referred to him as anything but the full Lucian, just as I was always Villiam to him, though occasionally with mutual acquaintances he was prepared to refer to me as Bill. Early on in his life, of course, the name Freud had stood him proud – it had been his password, while the family diminutives “Lux”, “Luce” and “Lou” had conferred street cred, or so he thought, when used by his Paddington pub acquaintances. He liked to feel that he could flit from one end of the social scale to the other, dukes to dustmen in a blink. He had the confidence that comes of intense curiosity coupled with wide engagement.

The first time we met was in late 1973. I’d been summoned down from Newcastle by the Sunday Times Magazine to produce what was to be the first ever feature article about this not yet celebrated 50-year-old, a painter unconnected with the standard avant garde. Why me? In 1970, Alan Ross’s London Magazine had published an essay of mine, Stranded Dinosaurs, in which I deplored the lack of attention paid to a number of middle-generation painters working in London – Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud and others – without realising that they themselves might go to the trouble of reading what I’d written.

And now, I was told, there was to be a Freud show at the Hayward Gallery, serving as second feature to what, obviously, would be the bigger draw: a Munch exhibition on the main floor. It was a stopgap, I later learned; somebody else’s retrospective having fallen through.

I, too, was a stopgap enlisted from afar. Mark Boxer, an editor at the Sunday Times Magazine, had thought up a list of probing questions for me to use, but failed to alert me to the fact that someone before me had been commissioned to do the article and that his inquiries had flustered Freud to an alarming degree. Most likely I would likewise be found objectionable, but it was worth a try.

I’d known virtually nothing about the man or his work until three years before, when I’d seen several paintings in West Hartlepool of all places, shown courtesy of the dealer Anthony d’Offay and on the initiative of the curator of the municipal museum, who had encountered Freud as a tutor at the Slade.

My first sighting of him was by arrangement one afternoon at the d’Offay gallery in London. I noted the good cut of the shabby overcoat and we shook hands, whereupon he smiled evasively and nipped off down Bond Street, only to reappear after dark some hours later in Islington, ringing the bell and banging the door of the flat where, he’d been told, I was staying the night. I invited him in but he lingered on the step, an impressive car behind him parked obliquely in the otherwise empty street. His breath steamed and no, he said, he simply wanted to make an arrangement for the following day: 19 Thorngate Road, a cul-de-sac, he stressed, in Maida Vale. At 10. “Thanks awfully,” he added.

What a day it turned out to be. Initially there was just the one painting to see in a bedroom studio: Large Interior W9, two women ignoring, or possibly unaware of, one another. The seated elderly one was his mother, he told me; she was facing away from a youngish, rapt, naked but blanketed figure behind, on a bed, arms clasped behind her head. We looked and looked, then without warning Lucian ducked behind a screen, struggled a little, or so it seemed, re-emerged in a green cord suit and off we went in the Bentley, speeding to Soho, where a double yellow line afforded parking space outside a restaurant. There we lunched, Lucian paying from a wad in his back pocket.

As we left – by which time there was a swatch of parking tickets to be tossed in the gutter – he greeted a young woman, not introduced, and gave her a lift to a bank. In she went, quickly reappearing with a plump carrier bag, handed this over and left us, murmuring something I didn’t quite catch.

Back in Thorngate Road, Lucian nipped upstairs and shoved the bag into his cupboard. He seemed pleased. “I’m going bankrupt,” he explained.

First thing that morning, I’d told him his private life was no concern of mine. He was to remind me of this frequently over the years, for from then onwards I was attracted and entertained by his stories, his thoughts, his attitudes and ardent way of life in and around the paintings.

In the course of that freezing November afternoon, as he drove me from place to place where pictures were to be seen, I felt myself becoming attuned. We stopped off at a garage owned, he said, by an acquaintance of his, a former jockey and sporadic antique dealer – he wanted him to check the throttle, or something. By mid-afternoon snow was falling, and so, leaving the car, we continued by taxi to a mews in Belgravia, where he showed me an impressively tall painting of the view from a window of decrepit backs of houses, overlooking a patch of waste ground strewn with mattresses and builders’ debris. I then produced my tape recorder and, without feeling any need to refer to Mark Boxer’s questionnaire, began what was to be the first ever Lucian Freud interview.

“Freud lives and moves one step ahead of the redevelopers,” I subsequently wrote. Temporary housing meant he had no phone, and so, itching to check through my article with me and anticipating a prolonged trunk call, he called on a girlfriend, who to her husband’s annoyance let him use hers. There were one or two details he thought worth adjusting, but, to my surprise, no complaints, and our conversation warmed up to such a degree that within half an hour it settled into anecdote and throwaway remarks, such as were to enliven innumerable calls to come.

Good to talk on the phone. Not that I ever had his number. He wasn’t connected until the late 70s (and thereafter frequently had the number changed) and so, while the initiative was his, I could always interrogate him, often at length, and fell into the habit of taking notes as I listened. In the course of that first call he went through what I’d written briskly, adding parentheses. Concerning the waste ground picture, he remarked that it related to the death of his father in 1970. It was a painting of temporariness. The lifespan of things.

“I feel a bit hopeful about my work at the moment – but then it varies terribly from day to day. I felt much more hopeful two days ago.”

Not long after the article “Lucian Freud: the Analytical Eye” appeared, I succeeded Bruce Chatwin as the Sunday Times Magazine’s art adviser, an enjoyable perch, working alongside two old friends of Lucian, Francis Wyndham and Bruce Bernard, before moving to the Observer, where, as art critic, I remained for 23 years.

In that period the term “School of London”, proposed by the painter RB Kitaj and applied to associates of Bacon and Freud – among them Auerbach, Andrews, Leon Kossoff (and Kitaj) – became recognised as a tag useful for promotional reasons yet tiresome for those stuck with the label. It did at least signal a robust faith in the persistence of painting, its essential purpose being, in the widest and deepest sense, modern life portrayed.

In the light of this, Freud’s Large Interior W11 (after Watteau), the centrepiece in As of Now, a group exhibition I put together for the Peter Moores Foundation at the Walker Art Gallery Liverpool in 1983, came to be regarded as something of a frontispiece to the School of London. The idea of a painting of several people in the artist’s recently acquired Holland Park studio, all intimately related to him and not quite connecting with one another, was a take on Watteau, a nod to Courbet’s epic The Painter’s Studio and a demonstration of what could be accomplished on a large scale under generous skylights. Paintings of the outrageous and seemingly larger-than-life dressing-up artist Leigh Bowery followed not long after.

Lucian got into the habit of asking me, as he asked one or two others (primarily Auerbach), to come and take a look at each painting on the go, once it developed beyond the stage of being, obstetrically speaking, viable. These viewings were usually early morning, so as not to intrude on working hours. Obviously I knew that I was summoned not to comment, really, but to be a spare pair of eyes, prompting Lucian to peer forward for a closer look as though checking for nits. He would talk about creating air around his figures, insisting that every square inch was of equal importance. “Background” wasn’t to be unfocused, as in a photograph; it had to be worked at like all else, paint being the means of convincing the onlooker that such a thing as a picture had more solid an existence (and better prospects) than we ourselves, or any old mattress, say. Any painting not fully charged was liable to end up talkative, so to speak, not telling.

Breakfasts were included, baked meats (woodcock in season) and every so often deep-fried parsley.

These previews were part of what had become a busy, compartmented schedule. As David Dawson, his assistant from the early 90s onwards, put it, “Lucian packed a lot into a day.” There were forays at all hours, studio appointments day and night, and he was uneasy if sitters or visitors overlapped. More than once in the early 90s, Bowery passed me on the stairs, unrecognisable – that’s to say ultra ordinary – in anorak and wig.

In the late 80s Lucian became unnerved when James Kirkman, his then dealer, proposed publishing a catalogue raisonné and that I should do the writing. I felt dubious about the idea. Premature, surely? As it was, Lucian soon put a stop to it. “Villiam, would you perhaps mind very much if we didn’t do the book?” We celebrated the cancellation with lunch at the River Cafe following a bobsleigh-style run in the Bentley through the backstreets of Fulham, Pluto swaying resignedly on the back seat as the G-forces kicked in.

Speed was itself celebratory. Whenever I was the driver, Lucian, clutching at the door handle, would advise me to accelerate from outside 36 Holland Park straight into busy Holland Park Avenue; the quicker one went, he explained, the less the likelihood of being entangled in idling traffic.

Circumstances changed drastically in the early 90s. Having left Kirkman, Lucian was taken on by William Acquavella in New York, whose eye for quality and nose for a deal helped extend the Freud reputation and swell prices to such a degree that, relatively speaking, his famously huge betting losses meant rather less to him than in earlier years.

He came to regret that he no longer had a London gallery to show in. The solution was to exhibit groups of new works instead in public galleries, before sending them off to New York, beginning with displays at the Whitechapel in 1993 (touring to the Prado and the Met), Dulwich Picture Gallery in 1994 and Kendal in 1996. I became increasingly involved in such shows, the most taxing being the 80th birthday retrospective at Tate Britain in 2002. (Talking of which, Lucian was keen to point out: “Tate Modern is wrong on every level. EVERY level.”)

In 1998 I made a start on what originally was to be a short Freud monograph. Lucian told people it was to be the First Funny Art Book, and daily on the phone he would ask: “How old am I now?” When he grumbled that these taped hours of picture talk and slander-rich gossip were distracting, and that he wanted to be known by his work alone, I would remind him that he liked Van Gogh’s letters, loved Delacroix’s diaries, and that he had often said how good it would be to know more about Titian and even, maybe, find out who Giotto really was. “Oh all right, then,” he would say, breezily unconvinced.

All went well until I showed him a couple of draft chapters and, understandably perhaps, he freaked. After quite some discussion we agreed that I should desist and that “a novel” might appear after his death. “Hello Villiam, how old am I now?” continued to be one of his standby opening gambits in phone conversations.

We’d often talked about how good it would be to assemble a Constable exhibition in which we’d have portraits put on a par with the landscapes. The opportunity to do just that was given to us at the Grand Palais in Paris, an exhibition that opened shortly after the Tate retrospective closed. The title John Constable: le choix de Lucian Freud proved to be a highly effective come-on not only with a French public but with other painters, Jasper Johns among them, who envied such freedom to elevate paintings above academicism.

Lucian’s involvement was sporadic and exhilarating. We spent evenings going through the Constable catalogues and had sessions at the V&A, the British Museum Print Room and in the Tate stores. Lucian wrote several effective letters to secure loans and even succeeded, against the odds, in getting the Art Institute of Chicago to lend its big and splendidly convulsive Stoke-by-Nayland, a painting with which he identified most of all. It took him back to his wayward student days at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing: parochial landscape bursting into sublime unruliness.

Once again, a few years later, a proposal for a catalogue raisonné was floated, this time with the involvement of Acquavella Galleries. Again, Lucian regarded such a project as interference and (like my book) premature. To him it seemed reasonable enough to list as fakes such works as happened to have fallen into the hands of people he particularly disliked. Scholarly insistence on consistency and trifling accuracy was irritating, and this second attempt was, if anything, more intrusive than before. “I want to close it down,” he told me. “I mean down and out. It’s more and more depressing.”

Lunching one day at Clarke’s in Kensington Church Street, Lucian’s local, we noticed that Sister Wendy Beckett, the art-loving nun, was being thoroughly well dined some distance away in a window seat. Though fobbed off initially, she approached our table for the second time with an air of tentative humility, grabbed my hand and spluttered a plea: “There’s something I’ve longed to ask you two gentlemen. Do you believe that little cats and dogs go to heaven?” Lucian eyed her, wondering quite what to make of her, wimple and all. Momentarily lost for words, he cleared his throat, then, with a nod and evasive twitch, came up with a reasonable answer: “I have to say… I really don’t know.”

She retreated, yet she had been on to something. Maybe she scented the affinities. Certainly, Lucian’s feel for dogs and horses, for their innocence and appetites and what we may perceive as intuition, was revealed in his paintings of them. The one charity he always supported was the Injured Jockeys Fund.

The gambling and betting dwindled in appeal in later years. His greater disposable income became such that it was no longer much of a thrill to achieve dramatic losses. Yet the pursuit of speed, love of the chase, remained consistent urges. Lucian admired Lester Piggott to the point of hero worship, relishing what he knew of his taciturnity, his tax problems, his sardonic zest, the utter pluck of crouching above the saddle and willing the win. Tenacity, he maintained, was a form of honesty. And knowing when to lay off and let go was vital, hence his readiness to slash or put his foot through anything that veered into cliche or stodge. Often (particularly with self-portraits) a painting would seem predisposed to become a wrong ’un. All paintings, he always said, whatever (or whoever) the subject, are portraits, self-portraits even. “Paint ages like we do.”

I never sat for Lucian, though he did suggest it more than once. “Looks too much like Lytton Strachey,” he explained one evening, when someone in a North Kensington Spanish bar asked him why not. I didn’t because I hadn’t the time, and then sitting for Auerbach, two hours once a week from early 2003 onwards, proved a manageable alternative. So Lucian took to treating me as a handy channel of communication between the two of them. “Any messages?” he would ask. “Are you Franking tonight?”

Early on, when I asked him what he might do to occupy himself if old age, say, prevented him from painting, he said unhesitatingly that he would sit for Frank. That didn’t happen.

“What makes dukes tick?” I asked him idly one afternoon, hoping to provoke reminiscence. He’d made a point of being friendly with two or three at any one time over the years. He thought for a moment. “What d’ you mean?” he asked. “People aren’t clockwork.”

• The Lives of Lucian Freud: Youth, 1922-1968 by William Feaver is published by Bloomsbury, £35.

Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits is at the Royal Academy, London, 27 October to 26 January 2020

No comments:

Post a Comment