|

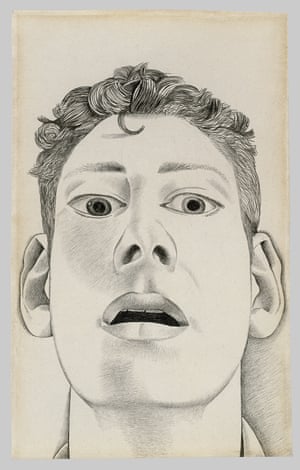

| Freud's Reflection With Two Children (Self Portrarit), 1965 |

Lucian Freud: The Self-portraits; Gauguin Portraits review – violence and mania

Lucian Freud: The Self-portraits; Gauguin Portraits review – violence and mania

Royal Academy; National Gallery, London

Lucian Freud’s presence pulses menacingly throughout a thrilling show of self-portraits, while Gauguin, in a neighbouring blockbuster, sees himself as the suffering outsider

RACHEL COOKE

Sunday 27 October 2019

The first picture in the Royal Academy’s exhibition of self-portraits by Lucian Freud dates from 1948 and is titled Startled Man. It is a pencil drawing, but you would no more refer to it as a sketch than you would refer to a three-course dinner as a snack. Freud would have been 25 when he made it and, if not already married (to Kitty Garman, one of Jacob Epstein’s daughters), then soon to be so – and in some ways, its immaculacy seems to speak to that moment. The artist’s depiction of his youthful self is boyishly sensual: his lips like pillows, his skin as smooth as a sheet stretched over a mattress. Freud’s new status must, at the time, have seemed surprising, not to say alarming, and here he bottles that incredulity for posterity. You can almost hear the sharp intake of breath.

But look more closely, and something else emerges. Freud’s head is tipped back, as if there were invisible hands at his throat, or someone yanking his hair from behind. This creeping violence sets the tone for much of what follows. Freud’s self-portraits (there are 56 here, some of them rarely seen in public) are all sorts of things: tender, witty, experimental and – yes, that dread word – visceral. To walk around this show is to be powerfully aware both of his intense single-mindedness – the sheer quality of his concentration – and of his abiding fascination with the idea of the shifting, slippery self; the experience is a little like being watched. But if some red thread does link them, it is surely this inescapable menace.

The curators, Jasper Sharp of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, and the artist David Dawson, Freud’s longtime studio assistant, suggest that his self-portraits have an elusive quality, one that brings to mind a game of hide and seek. I know what they mean – in Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1978, it is as if Freud is being swallowed by fog, like some Victorian spectre – but it’s also the case that I’ve seldom felt the presence of an artist in a gallery so strongly as here. Even when he’s barely in the picture – just a pair of feet in the corner (Naked Portrait With Reflection, 1980), or a shadow falling across an unmade bed (Flora With Blue Toenails, 2000-01) – his presence is palpable, a pulse throbbing in your ear.

In Man With a Feather (Self-Portrait), 1943, Freud paints himself in a dark jacket and a narrow tie: gangsterish accoutrements that are at stark odds both with his blank, rather innocent face and the feather that he holds in his hand. In Hotel Bedroom, 1954 (the last painting he ever did sitting down), he looms over his second wife, Caroline Blackwood, like a cliff. In Reflection With Two Children (Self-Portrait), 1965, his daughter and son Rose and Ali Boyt are tiny in one corner, while he gazes into the mirror he placed on the floor for the purposes of painting the picture, huge and God-like.

Though Freud insisted that his work was “purely autobiographical”, he wasn’t keen on the idea of narrative; his fixation was with boiling people down to their essence. But this painting tells its own story. Here is a battle (for time, for space, or perhaps even for primacy) in which he appears as the victor. Finally, there is Self-Portrait With a Black Eye, 1978, made after an altercation with a taxi driver, in which the physical result of violence is the source of both pride and irresistible curiosity (another kind of man, and even of artist, would have been resting with a steak on his face, not standing in front of his easel).

This is a magnificent and utterly absorbing exhibition: stopped clocks, and all that. Like a diver, you go down and down, only to emerge with a slight sense of the bends: outside, the world is not, after all, controlled by the deity that is Freud. It covers a life, and because of this it presents the remarkable scope of the artist’s talents, from the enamelled exquisiteness of the early work to the impasto of the late; from the smaller canvases he favoured at the start of his career to the outsize ones he made towards the end. Thanks to this, too, it’s moving in a very human way.

Here, paint represents years: the thicker it grows, the greater the intimations of mortality. Somewhere towards the end, he makes Painter Working, Reflection, 1993, a self-portrait that is seemingly without vanity – the slippers the nude Freud wears in it have a singular pathos – but that also, by sheer dint of its size, demands that you pay attention to the ruined realms of its subject’s body. It is marvellous and noble and strange, and you feel better for having gawped at it: ready, as it were, for the long fight ahead.

Gauguin Portraits at the National Gallery is a blockbuster show. I don’t mean this as a criticism. But some of these images are so well known by now, even if only in their generality, that it’s hard, sometimes, truly to see them. For focus, I concentrated my gaze on the artist’s self-portraits, of which, thanks to his self-obsession, there are several. Lively and provocative, they are also quite deranged: egomania in mustard yellow and liverish green. In Christ in the Garden of Olives, 1889, Gauguin depicts himself as Christ on the eve of his betrayal, thereby drawing parallels between Jesus’s persecution and the isolation he himself experienced as an artist for whom success was elusive. In Self-Portrait, 1890-94, meanwhile, he presents himself as a “savage from Peru”.

No wonder, then, that I turned to his Anthropomorphic Pot, 1889, with a smile. I’ve always liked Gauguin’s ceramics – they are free-thinking in ways that his paintings only aspire to be – and this is a particularly endearing example: grotesque, humorous, and then, as you realise that the Gauguin-like figure that forms the vessel has its thumb in its mouth, finally rather touching. Here is an artist suddenly at ease: doing as he pleases, cartwheeling in clay.

• Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits is at the Royal Academy, London, until 26 January 2020

• Gauguin Portraits is at the National Gallery, London, until 26 January 2020

No comments:

Post a Comment