|

| Marcel Proust |

Top 10 fictional takes on real lives

From Woody Allen reimagining Van Gogh as a dentist, to Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, the joint winners of the Republic of Consciousness prize select the best reimaginings

Wed 3 Apr 2019 15.41 BST

Abiography is the story of a real life. A novel is an invention. The overlap is clear, because stories about real people, where individual consciousness meets the historical record, are inventively inflected, and in any case, as Proust said, “the facts of life do not penetrate to the sphere in which our beliefs are cherished.” But invented stories should still respect real sources: in Murmur, my fantasia on themes inspired by the life of the logician and computer science pioneer Alan Turing, I had no wish to attribute to a genius things he did not say, and so there is a Turing avatar, Alec Pryor, doing the wondering for me. Alex Pheby’s work, too, has always dealt with the ways life and writing intersect, and with the combination of lucid perception and fantasy to be found in both fiction and the experience of mental illness. Here is our joint selection of 10 fictional works inspired by real lives.

1. Swann’s Way (Vol One of In Search of Lost Time) by Marcel Proust

Is A la recherche du temps perdu an autobiographical novel? Discuss. The Narrator is perhaps best understood as a persona of the author, and the whole project as an attempt by Proust to understand, dramatically, and more ambitiously than any novelist before him, the simultaneously real and inexistent life of the mind. I am a late-adopter of Proust, and still reading the novel sequence. Swann’s Way leads from the narrator’s late 19th-century childhood in Combray to his love for Swann’s daughter Gilberte, and on (or rather back) to Swann’s passion for Odette de Crecy. The reader is pulled over the threshold of the affair along with Swann, so that, like him, we can’t tell for certain if anything has begun. WE

Is A la recherche du temps perdu an autobiographical novel? Discuss. The Narrator is perhaps best understood as a persona of the author, and the whole project as an attempt by Proust to understand, dramatically, and more ambitiously than any novelist before him, the simultaneously real and inexistent life of the mind. I am a late-adopter of Proust, and still reading the novel sequence. Swann’s Way leads from the narrator’s late 19th-century childhood in Combray to his love for Swann’s daughter Gilberte, and on (or rather back) to Swann’s passion for Odette de Crecy. The reader is pulled over the threshold of the affair along with Swann, so that, like him, we can’t tell for certain if anything has begun. WE

2. Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar

On the brink of death, the Roman emperor Hadrian writes to his successor, Marcus Aurelius, about his life, his victories, and his philosophy: a proto-stoicism of self-critical candour that values stability above triumph. It is this political sangfroid, the reverence for ancient ideals of culture and conservation ranged against the tumult of events themselves, that gives the emotional centre of the book – Hadrian’s relationship with the Greek boy Antinous – its surprising depth. Yourcenar’s research is fully absorbed, and the lapidary style, learned but intimate, evokes a monumental figure in glimpses, or perhaps cries. Above all, said Yourcenar, her novel was to be thought of as the “portrait of a voice”. WE

On the brink of death, the Roman emperor Hadrian writes to his successor, Marcus Aurelius, about his life, his victories, and his philosophy: a proto-stoicism of self-critical candour that values stability above triumph. It is this political sangfroid, the reverence for ancient ideals of culture and conservation ranged against the tumult of events themselves, that gives the emotional centre of the book – Hadrian’s relationship with the Greek boy Antinous – its surprising depth. Yourcenar’s research is fully absorbed, and the lapidary style, learned but intimate, evokes a monumental figure in glimpses, or perhaps cries. Above all, said Yourcenar, her novel was to be thought of as the “portrait of a voice”. WE

3. An Imaginary Life by David Malouf

I read this short, brilliant novel by the Australian poet and novelist about the Roman poet Ovid’s exile in Tomis, when I was first wondering what Turing would make of his own predicament. (Turing was convicted of gross indecency with another man, and sentenced to a corrective hormonal regimen, or “organotherapy”, in 1952.) In the unspoken alliance he forms with a wild boy, the sceptical but passionate Ovid confronts bodily decay, the limits of language, and a spirit-world informed by the shamanic people among whom he now lives. It is a fiction “with its roots in possible event”, Malouf tells us, but it is also a gloss on the Metamorphoses themselves. WE

I read this short, brilliant novel by the Australian poet and novelist about the Roman poet Ovid’s exile in Tomis, when I was first wondering what Turing would make of his own predicament. (Turing was convicted of gross indecency with another man, and sentenced to a corrective hormonal regimen, or “organotherapy”, in 1952.) In the unspoken alliance he forms with a wild boy, the sceptical but passionate Ovid confronts bodily decay, the limits of language, and a spirit-world informed by the shamanic people among whom he now lives. It is a fiction “with its roots in possible event”, Malouf tells us, but it is also a gloss on the Metamorphoses themselves. WE

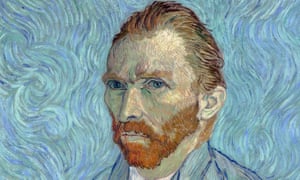

4. If the Impressionists Had Been Dentists: A transposition of temperament by Woody AllenThis piece is one of many Allen wrote in the 1970s for the New Yorker. Vincent Van Gogh corresponds with his brother Theo about suffering, money worries and lust. He is identifiably Van Gogh, and also a dentist: “I took some dental x-rays this week that I thought were good. Degas saw them and was critical. He said the composition was bad. All the cavities were bunched in the lower left corner. I explained to him that that’s how Mrs Slotkin’s mouth looks, but he wouldn’t listen. He said he hated the frames and mahogany was too heavy.” WE

5. The Blue Flower by Penelope FitzgeraldThe last, and arguably best, of Fitzgerald’s novels is a lattice of bright moments from the life of Fritz von Hardenburg (1772–1801), the romantic poet Novalis: the first view of the von Hardenburg household on washday; the fingers of a fellow student severed in a duel and kept warm in Fritz’s mouth; the moment of his heart’s surrender to 12-year-old Sophie von Kühn; the matter-of-fact end – consumption – that brushes all the characters aside. The frame holding these pieces together is a style, felt but unattributable, like a hand lodged suddenly and not quite reassuringly in the small of one’s back. WE

6. You Could Do Something Amazing with Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat] by Andrew HankinsonA formally adventurous object lesson in combining real life and the artifices inherent in fiction, this book forces the reader, by a brilliant use of second person narration, to empathise with killer Raoul Moat, as he fled capture across the north east of England in 2010. The book treads an uneasy line through Moat’s last days, patching documented fact and transcripts together with an almost Choose Your Own Adventure style. Simultaneously literary experimentation and a fascinating account of a case. AP

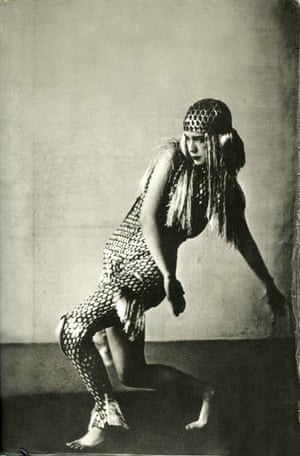

7. Dotter of her Father’s Eyes by Mary and Bryan TalbotThis takes what little is known about the youth of Lucia Joyce – dancer daughter of James Joyce and Nora Barnacle – and maps it against Mary Talbot’s own life, with Bryan’s restrained and precise illustrations intertwining the two stories. While Mary’s and Lucia’s stories are very different, there are similarities in their relationships with their parents, in worlds often dismissive of women. Mary beautifully weaves a universal tale out of the particularities of both of their experiences. The book is capable, through a kind of sacrificial revelation of the author’s own autobiography, of addressing the troubling story of Lucia without appropriation, and of working with the very limited information available to create something that feels fully realised. AP

8. Artemisia by Anna BantiIn 1944, Anna Banti’s first attempt at Artemisia was destroyed by war, and the book she eventually published three years later is the recreation of that lost manuscript. This resulting self-proclaimed “historical-literary symbiosis” is all at once a novel, a history and a biography, told through a series of journeys both through 17th-century Europe and the life of the artist Artemisia Gentileschi. Gentileschi’s life was difficult and Banti recreates it in a way that is not only intoxicatingly beautiful but also deeply troubling, simultaneously evoking her own experience in wartime fascist Italy. AP

9. Novels in Three Lines by Félix FénéonBetter known as the man who championed Seurat and first published Joyce in France, Fénéon was an anarchist, critic and prolific writer. Novels in Three Lines represents most of his contributions to the 1906 faits-divers newspaper column in Le Matin, tiny vignettes on the subject of provincial scandals and crimes. Gathered by his lover and discovered after his death, these hundreds of three-line miniatures are constructed as well as many novels and often provide as much narrative pleasure: “The corpse of the sixtyish Dorlay hung from a tree in Arcueil, with a sign reading, ‘Too old to work.’” AP

10. Memoirs of My Nervous Illness by Daniel Paul SchreberWhile Memoirs of My Nervous Illness is only rarely read as a piece of fiction, and its author would have been very resistant to it being described as such, Schreber’s writing says more about the human condition than most novels. His fraught and be-devilled experiences in German 19th-century lunatic asylums provide fascinating insights into what “reality” means for all of us, and how it can escape our grasp. His memoirs are written with a lucidity that prevents us from holding Schreber at arm’s length, forcing us to take what he felt were his “religious beliefs” seriously. Like the best novels, this book makes us look at the ideas that underpin our own realities and question their validity. AP

No comments:

Post a Comment