Notes on a scandal … Lewis Morley's 1963 photograph of Christine Keeler. Photograph: Lewis Morley/National Portrait Gallery

Notes on a scandal … Lewis Morley's 1963 photograph of Christine Keeler. Photograph: Lewis Morley/National Portrait GalleryChristine Keeler's nude photograph: still sexy and subversive, 50 years on

The notorious post-Profumo shot, now on show at the National Portrait Gallery, has long inspired artists to take a pop at sexism

JONATHAN JONES

Wed 1 May 2012

An iconic nude has just gone on view at the National Portrait Gallery. Lewis Morley's photograph of Christine Keeler is included in a display to mark the 50th anniversary of the Profumo affair, the Tory sex scandal that rocked – or perhaps it is fairer to say delighted – 1963 Britain.

The display reveals that Morley photographed Keeler as publicity and screen-testing for a film about the events that led to the resignation of John Profumo, secretary of state for war in Harold Macmillan's government. She was obliged to be photographed naked by her contract with the film company, so Morley devised the famous shot in which she straddles a modernist chair and gazes smokily at the onlooker. It is a brilliant tease and still very sexy.

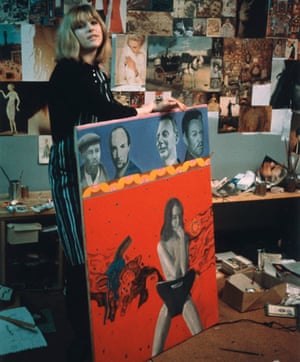

Joe Orton struck the pose for his own portrait, at once mocking its seduction and using it to allude to his own rebellious identity as a gay writer. A less famous quotation is in a lost painting by Pauline Boty, which is revisited at the NPG through photographs of Boty with her work. Boty, the most celebrated woman in the pop art movement of early 60s Britain, created several paintings about the Profumo affair, including one in which she copies the classic photograph of Keeler. It is now mysteriously missing.

Looking at pictures of Boty, who died from cancer in 1966, alongside the incandescent image of Keeler raises questions about women, art, beauty and the 1960s. Boty was herself regarded as a beauty, and it is no coincidence that visual documentation of her art often seems to portray her with it. Meanwhile, Keeler was in a tradition of unrespectable women in the public eye that goes back to Restoration royal mistresses such as Nell Gwyn. Compare her with Charles II's lover for yourself at the National Portrait Gallery.

So then: was the art of the pop era good or bad for women? Becoming an icon gave Keeler a career that still continues. Meanwhile, Boty was treated in the media of the time as a swinging London star who just happened to paint. She herself portrayed Keeler, so she must have found her notorious image subversive and fascinating. All this added to the heady mix of liberation and oppression that by 1970 would lead to the publication of The Female Eunuch– and the rise of a new feminist movement.

DRAGON

No comments:

Post a Comment