|

| ‘I want to see the devil in us all’ … a 1980 self-portrait. |

'He was a sexual outlaw': my love affair with Robert Mapplethorpe

Look at the pictures. Robert left a legacy of thousands of beautiful photographs of faces, flowers and fetishes when he died of Aids on 9 March 1989 at the age of 42. He had assaulted American concepts of race, sex, gender and morality. Born in Floral Park, New York, in 1946, he was on trial all of his short life, anti-gay legislation making him a sexual outlaw. His work too was on trial: it ran gauntlets of homophobia to hang today in such international sanctuaries as the Tate in Britain, and the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In 1990, at the height of US hysteria over Aids, a witch hunt in Cincinnati put seven of his frames on trial, aiming to sort art from obscenity. Robert’s photos won.

He changed popular culture. The sort of sex pictures he dared to shoot are now shot every day by millions, minus his style, on Snapchat and Grindr. It is a victory that he is being celebrated this year in two major exhibitions in the US, and in the documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, out next month.

The romantic comedy of our bromance bloomed the instant Robert opened his gorgeous portfolio, mind and body for me when I was editor of Drummer, a San Francisco magazine targeted at gay men with an interest in leather. It was the Titanic 1970s, when the first-class party sped on, innocent of the iceberg of Aids that lay dead ahead. Everyone was polyamorous. He was more beautiful than the pouty Botticelli rock star Jim Morrison. We became bi-coastal lovers for more than two years and remained friends for ever. We fricated our edginess together. We were both re-quivering Catholics mixing the sacred and the profane. An acolyte of Rimbaud, he was keen on my book about Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan. It was sex, love, art, letters, phonecalls and business. It was life.

He described ideal passion as “intelligent sex”. One night, during stoned pillow talk, he exhaled a stream of Kool menthol smoke: “I want to be a story told in beds at night around the world.” We both giggled.

In San Francisco in the late 1970s, Robert lived a free life shooting some of his most famous leather photographs. Liberated from the controlled environment of his Manhattan studio, and unobserved by critical New York eyes, he found joy in gonzo locations. I watched him at work in the Twin Peaks condo where he shot my other lover, physique champion Jim Enger. I drove him to scout the cement bunkers on the Marin Headlands for the “piss-photo” shoot that gave us Jim and Tom, Sausalito – a shot, now owned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in which one man urinates into another’s mouth. I vouched for him when he wanted to shoot the dominatrix Cynthia Slater in the dark dungeon of the Catacombs fisting palace.

His pictures seduced me. In 1978, I gave him his first Drummer cover, providing my friend Elliot Siegal as his model. We published nine of his fetish photos and profiled him in what was his first coverage in the gay press: “His camera eye peels faces, bodies and trips. He photographs princesses like Margaret, bodybuilders like Arnold Schwarzenegger, rock stars like his best friend Patti Smith, and night trippers nameless in leather, rubber and ropes.”

Drummer needed his homomasculine photos of leathermen as urgently as he needed its 40,000 subscribers – to grow his fanbase when people still thought his last name rhymed with “apple” rather than “maypole”. He was drawn to Drummer because, at the age of 16, the Irish-Catholic boy from Long Island had had an epiphany while looking at beefcake photos of leathermen in gritty Times Square porn shops. He cut and pasted these “found” photos into the collages that were his first artworks, before he picked up his first camera, a Polaroid, in 1970.

The homomasculine power of those pictures excited him so viscerally that he swooned with a gut punch of carnal mysticism. The forbidden photos also outed his sadomasochistic identity in exactly the way that some Catholic boys suddenly discover that the muscular bearded Jesus hanging stripped and crucified over the altar is hot. He laboured throughout his career to inject that sex rush, that religious feeling, that existential frisson, into his holy pictures of leather sex, black men, celebrity women and flowers brilliant as night-blooming sex organs.

He was 29 when we first met, and he immediately gave me my favourite photo of himself. It is perhaps his only smiling selfie: a faun with tousled hair, his bare torso verging into the frame, one nipple revealed, his right arm outstretched horizontally across the white background, his right palm open, awaiting the rosy crucifixion he so desired.

Letters bonded us. On 10 April 1978, he wrote me a letter from Colorado. The London Times had sent him to photograph Allen Ginsberg “who’s had so many pictures taken already”. He moaned: “Ginsberg was a Jewish drag.” The poet made Robert sit through his lecture on William Blake. “Ginsberg did say (still in the lotus position) that he was getting into S&M. No blood, however. I’m going to turn out the lights and try to muster enough energy to ‘Jack’ off. Love, Robert.”

Robert was not just a photographer: he was an artist who was a photographer. He came alive, he said, after the Stonewall riot against the New York police, which began modern gay liberation in June 1969. He sped into the 1970s on charm, poppers and MDA. He made it his job to rub elbows and plough the pertinent at Warhol’s Factory, Studio 54 and Max’s Kansas City.

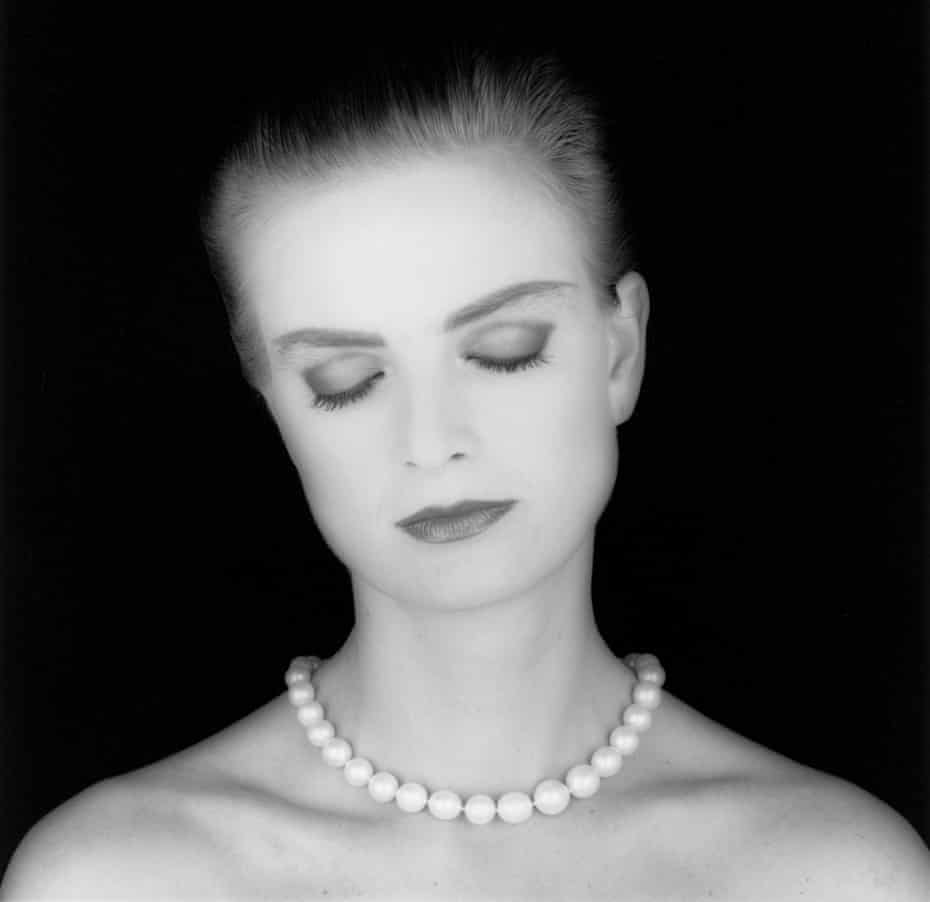

The bad boy had tuxedo elegance and leather attitude perfect for the jet set. He often wore a green velvet jacket for dressing straight at drop-dead soirees in London, New York, and Mustique with friends and faces he shot: Princess Margaret, Lord Snowdon, Carolina Herrera, David Hockney, Doris Saatchi, Bruce Chatwin, Lady Rose Lambton, Julian Sands, Marianne Faithfull, Yoko Ono, Keith Haring, Susan Sarandon, Thom Gunn, Philip Glass and punk Princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis. When he shot Katherine Cebrian, the elderly San Francisco grande dame, the bright silver studs on the back of his big leather belt spelled SHIT.

He was a hustler who did far more than shoot his own face and run into his darkroom to develop himself. In 1972, his first gay lover, David Croland, introduced him to the wealthy Manhattan art collector Sam Wagstaff. According to Robert, Sam said: “I’m looking for someone to spoil.” Robert grinned: “You’ve found him.” The new lovers shared the same birthday, 25 years apart. Robert gave his benefactor as good as he got. He introduced shy Sam to the leather demi-world at Manhattan sex clubs like the Mineshaft. He educated Sam about 19th- and early 20th-century British, French and American photographers. He caused Sam to change art history, persuading him to use his authority to convince reluctant connoisseurs (and buyers) that photography was as legitimate an art as painting and sculpture.

Sam bought Robert his first Hasselblad to shoot photographs for the new art market Sam had created. When Robert introduced me to Sam in the restaurant at One Fifth, the elegant art deco building in New York, I watched him take Sam’s hand and pull back in surprise at the diamond ring Sam had slipped him. “Welcome back from San Francisco,” Sam said. Robert, swear to God, bit the diamond with his teeth. Sam laughed and whisked us up, up and away to his immense all-white penthouse atop One Fifth, where we sat on the tile floor chatting about the hundreds of photos by early masters spread out around us.

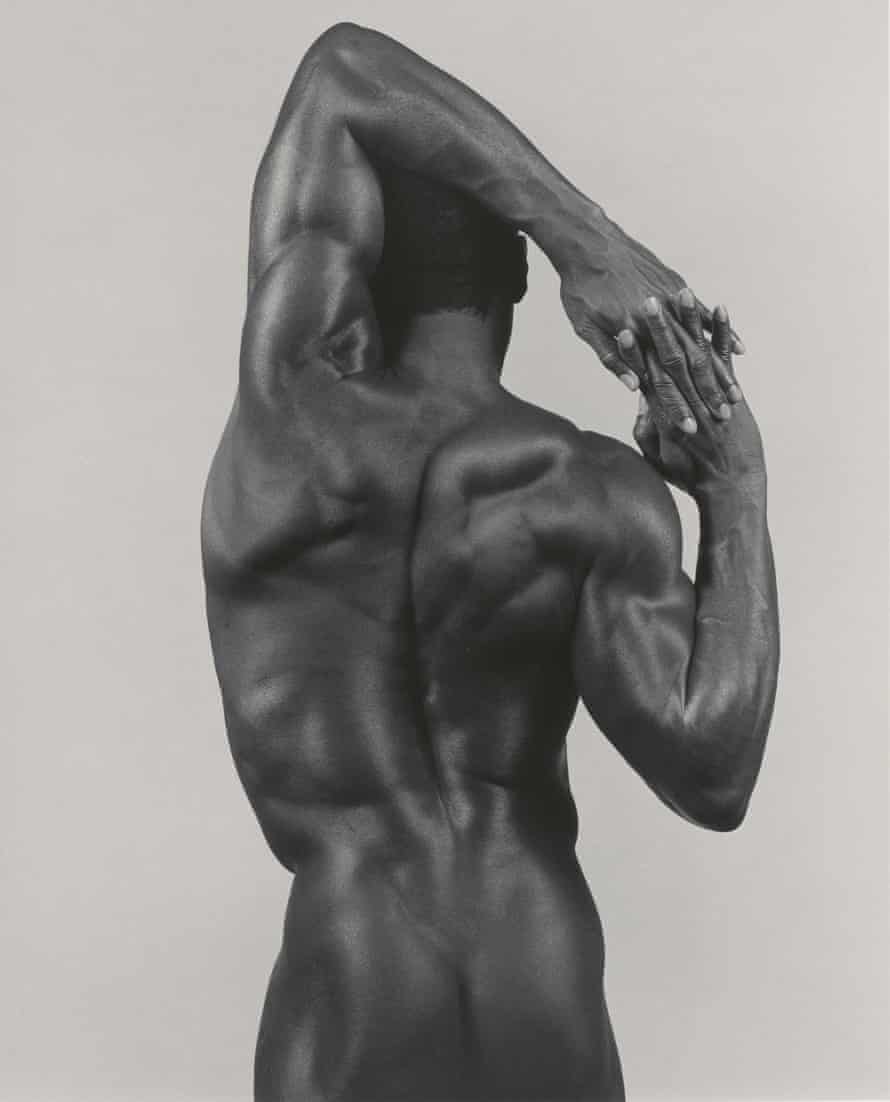

When the white photographer began cruising gay black bars, he turned race into a personal sex fetish. He also hired professional black models like his lover Milton Moore, whose penis he made exquisite in the now world-famous 1981 photo Man in Polyester Suit. He told Boyd McDonald of the Manhattan Review of Unnatural Acts that his favourite movie was Mandingo.

He sweated with white guilt trying to make his quest for black beauty keep him from the mortal sin of racism. He dedicated the last decade of his life to documenting famous black men, like the dancers Gregory Hines and Bill T Jones, while continuing to shoot unknown black models. He was an existential comedian. He knew that the most frightening thing in the world is a photo of a penis. He knew pictures of black men could add another level of terror to his work. So he upped the anxiety for his white liberal patrons and made the penises big and black. Provoking American paranoia, he took a side-on shot of a black model holding a gun just above his horizontal erection: Cock and Gun (1982). When his patrons blanched, he would double-dare them: “If you don’t like my pictures, perhaps you’re not as avant garde as you think.”

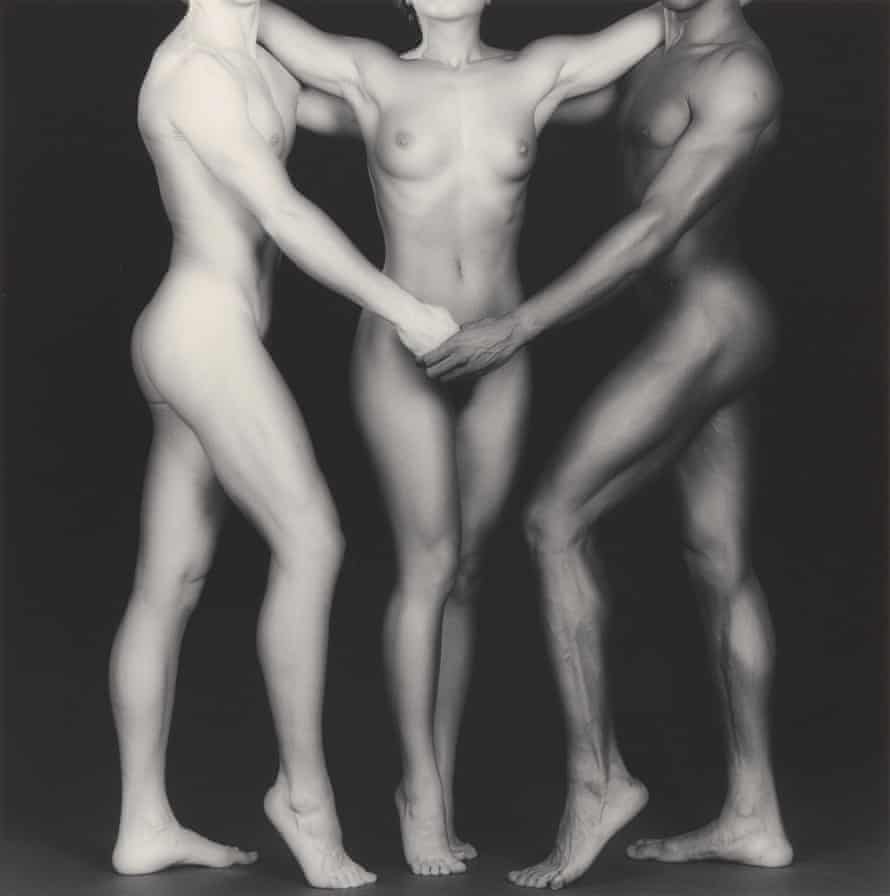

Ken and Lydia and Tyler, 1985

History forgets that Robert also exhibited under the radar in the gayly notorious Fey-Way Studios founded by the Oscar streaker Robert Opel, who ran his nasty bits past David Niven and Elizabeth Taylor on the live broadcast of the 1974 Academy Awards. At the opening, Opel exhibited one of Robert’s leather models, Larry Hunt, in a cage near Robert’s photo, titled Larry Hunt: Boots and Bench. Four months later, in July 1979, Opel was shot dead in his gallery, and Larry was abducted from a leather bar and killed. An urban legend about a “Mapplethorpe curse” arose, fed by the film Cruising with its S&M murders – and then Aids began hitting the headlines.

Suspecting the worst, Robert sped up the quantity and quality of his work to express his soul and build a legacy of more than 120,000 pictures. As his healthy beauty time-lapsed fast into the stoic beauty of the dying, he did not like eyes looking back at him through the camera. So he shot flowers and statues and objects that obeyed his direction and made no demands.

In 1984, Robert went to Heaven, the gay disco under Charing Cross in London, where he ran into his frenemy, film director Derek Jarman, who famously described Robert’s life as “the story of Faust”. Derek was going down one stairway as Robert, who did indeed say he had sold his soul, was climbing up another. Robert shouted: “I have everything I want, Derek. Have you everything you want?”

I intuited he would die young and wrote that about him in 1978. So I knew from the first to hold him fast. As I sit in my California garden among the tall calla lilies where Robert once sat, I miss his sweet face, lithe body and ironic voice, but his aura remains vivid – from his late-night phone calls, photos and letters.

“Jack,” he wrote on 26 July 1979, “if you’re not free for dinner tomorrow night, I’m going to beat you up. Love, Robert.” In his left-handed slant, he wrote on 20 April 1977: “I think you’re right about me needing a psychiatrist. I’m a male nymphomaniac. I’m never satisfied.” On 21 May 1978, as he was shooting photos of himself as both Satyr and Satan with horns on his head, to illustrate a leather-bound edition of Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, he wrote: “I want to see the devil in us all. That’s my real turn-on.” It was a private remark that echoed what Robert once said about his flower photos: “Beauty and the devil are the same thing.”

No comments:

Post a Comment