|

| Iris Murdoch David Levine |

She May Have Died in 1999, but Iris Murdoch Is the Perfect Novelist for Our Time

Her absolute refusal to judge her characters is an antidote to contemporary literary certainty.

For much of 2021, while putting the finishing touches on my own book, I served as a reader for a literary prize. I was excited—honored, even—to do it, and looked forward to deeply immersing myself in the fiction of this moment. And did I ever: I read at least the first chapters of more than 200 novels, turning my reading year into a kind of supersize survey course of contemporary literature. At first it felt great, as if I were tuned in to the frequency of our age. By the fall, though, I felt as though I was overdosing on the contemporary. It’s not that the literature of today wasn’t good—I read several wonderful books!—so much as that contemporary literature cannot help but be, well, contemporary.

Though most of the books were marked by either swooning lyricism or Didionesque aphoristic minimalism, this goes deeper than prose style. The problems, and the perspective on those problems, remained remarkably consistent from book to book. The moral and political frameworks of the novels—their ideas of what society is and how people should relate to it—had a uniformity as well. This would probably be true of any 200 novels taken from any single year, but in 2021 what this perspective often looked like was one of certainty—one of providing answers instead of asking questions, one of making sure the reader knew what the author’s position was and that that position was correct. In an era where all consensus seems to have broken down, and a year marked with incredible turmoil in every area of American life, such certainties have their uses, but when it comes to art, they often make the resulting work feel claustrophobic. There’s little room for the reader to do anything but nod in agreement and, often, be impressed by that swooning lyricism. As 2021 went on, I felt trapped in the now, during a year few of us enjoyed at all. I knew I needed a release, and, as surely as someone who had just decoded the clues for an escape room, I knew from where this release would come: the novels of Iris Murdoch.

And I wasn’t the only one. Coincidentally—or was it?—I saw Murdoch’s work being referenced in the social media feeds of many writers and critics I respected. It became widespread enough that the New Republic’s Alex Shepard asked on Twitter, “Who will write the trend piece we all need: why is everyone reading Iris Murdoch?” Murdoch didn’t write about climate change, or white supremacy, or how the online world has transformed human relations. So what is it about her books that turns out to be so perfect for our present-day anxieties?

Murdoch, an Irish-British novelist and philosopher whose career in fiction began with 1954’s Under the Net, has been providing all of us an escape, but her work is hardly escapist. Indeed, Murdoch believed, as she wrote in her essay “Against Dryness,” that the novel “can arm us against consolation and fantasy” and “give us a new vocabulary of experience, and a truer picture of freedom.” “Against Dryness” was written in 1961, when Murdoch herself had overdosed on the contemporary literature of her period, which she felt was often either too journalistic and sprawling or too “crystalline,” by which she meant a “small quasi-allegorical object portraying the human condition.” In either scenario, she also felt novelists were too besotted with post-Hemingway minimalist writing—that their prose lacked style and eloquence, and was used for “essentially didactic, documentary” reasons instead of as an imaginative medium.

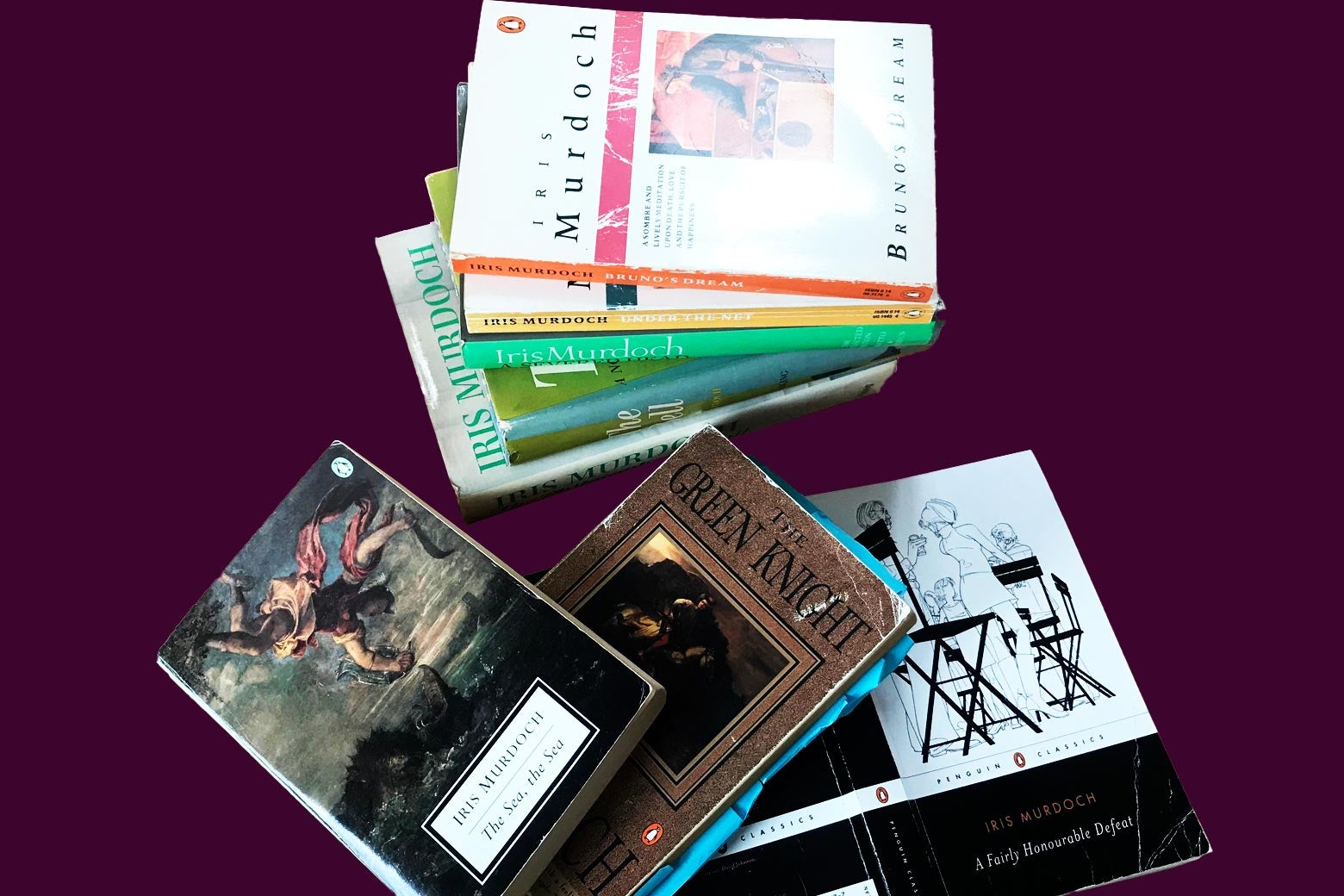

Murdoch attacked these problems in a body of work that is bewilderingly vast. Over the course of 40 years, she wrote 26 novels and multiple works of philosophy, alongside poems, short stories, plays, and voluminous private correspondence. Throughout, her idea of “eloquence”—prose that has imaginative verve, precision, and clear style without stooping to beauty for its own sake—shines through. Even minor novels like 1966’s The Time of the Angels have breathtaking passages like one in which Muriel, a young poet in her 20s who helps take care of her chronically ill cousin Elizabeth, looks in a mirror in her cousin’s room. “The room appeared again,” Murdoch writes, “but altered, as if seen in water, a little darkened in a silver-gilded powdery haze.” Only a few sentences later, it is revealed to us—although not to Muriel—that Muriel is obsessed with her cousin, caught between wanting to become her and wanting to possess her. The passage carries the reader along using subtle alliteration and assonance:

Muriel now looked into her own eyes, bluer than Elizabeth’s but not so beautifully shaped. As she saw that her breath was blurring the glass she leaned closer and pressed her lips to the cold mirror. As she did so, and her mirrored lips moved to meet her, a memory came. She had once and only once kissed Elizabeth on the lips and then there had been a pane of glass between them. It was a sunny day and they had gazed at each other through the glass panel of the garden door and kissed. Elizabeth was fourteen. Muriel recalled the child’s figure flying then down the green garden, and the cold hardness of the glass to which her own lips had remained pressed.

When Muriel removes her mouth from the mirror, she stares into it, entranced, as if “one might see suddenly shimmering into form the apparition of a supernatural princess” within its depths. This moment is beautiful, but its beauty is necessary: It sets up one of the motifs of the novel, with Elizabeth as a fairy-tale princess, blonde, sequestered, largely devoid of personality but still an object of obsession for everyone around her.

Perhaps due to her prolific output, Murdoch’s body of work circles the same set pieces, ideas, themes, characters, and obsessions again and again, combining and recombining them as she explores the struggle to be good in a world without God, the limits of self-awareness, and the disruptive power of love and sex. Cracking one of her books, you will likely find some of the following: academics and writers, manipulative charismatic geniuses, incest real or imagined, saintly teenagers, angry young men, civil servants, creaky old houses, descriptions of food, odd encounters with animals, and near or actual drownings. (Sadly, you will also encounter depictions of Jews that make us seem like creatures from another dimension, so alien as to be almost unfathomable, existing beyond normal categories of good and evil.) Rather than making the books feel repetitive, Murdoch’s circling of her various obsessions means that every time you finish one of her novels, your new understanding brightens and sharpens the experience of the books you’ve read before. The books become like Lay’s potato chips: Bet you can’t read just one.

A Murdoch novel pointedly refuses to stick to any one genre, opting instead to follow character and theme into whatever new container the book requires. For example, The Sea The Sea, which won the 1978 Booker Prize, reads at first like a recipe blog by an old man obsessed with tinned fish and ends feeling more like The Tempest, but not before it has taken a detour into a kidnapping plotline that must be read to be believed. Murdoch develops action and theme through analogy, sticking multiple characters in situations that reflect one another, and seem to comment on one another. Just as Hamlet contains multiple false kings, multiple sons who have lost fathers, and multiple attempts at flawed earthly justice, A Fairly Honourable Defeat, written in 1970, is a solar system of romantic relationships that slip out of their natural orbits and tumble toward a black hole of doubt and remorse. It’s also probably an allegory for the midcentury power struggles between analytic philosophy and moral philosophy in British academia. And a sex farce in which no one has any sex.

That’s the thing about Murdoch—there’s always another layer, one revealed through opposition and dialectic. She called literature a way to “re-discover a sense of the density of our lives,” and she revels in setting points of view, ways of being, perspectives on her themes against one another. And she refuses to take sides, letting the conflict that ensues create a deeper meaning than what would be possible if she indulged in moral clarity. It is this refusal to moralize, and her careful silence about her own beliefs, that sets her so deeply apart from contemporary writers. She feels no anxiety about proving that she “gets it.” It turns out to be quite a relief to read a novel that isn’t written from a defensive crouch but is instead truly open to multiple good, bad, and absurd attitudes. Murdoch remains true to her characters and their own blinkered perspectives, only openly judging them when they do something embarrassing. This can, at times, be quite provocative. In The Bell, Murdoch gradually reveals that Michael Meade, first presented as a closeted gay man, is in fact a pederast. But since Michael cannot admit this to himself, it is up to the reader to look beyond his own self-conception to get to the truth. (Murdoch, who was queer and whose letters reveal a discomfort with the gender binary, often featured gay men in her novels.) Meanwhile, Dora Greenfield, a young artist who has made a bad marriage because she does not know what she wants, is a frequent target of the book’s gentle derision.

Murdoch’s characters often seem surprised, as any psychologically realistic human being would be, to be stuck in a Gothic novel or a sex farce. Drawing from the great naturalistic writers of the 19th century, Murdoch wanted to reveal the ways that we do not know ourselves, do not understand the world or even our own actions. Or, as she put it in “Against Dryness,” “We are not isolated free choosers … but benighted creatures sunk in a reality whose nature we are constantly and overwhelmingly tempted to deform by fantasy.” Her narrators are unreliable, she means, because we are unreliable.

The Bell contains a hilarious sequence in which Dora confronts a familiar ethical dilemma: Should you give up your seat on the train for an old woman? She justifies not doing so by telling herself the woman probably doesn’t want the seat anyway: “Dora hated pointless sacrifices. She was tired after her recent emotions and deserved a rest. Besides, it would never do to arrive at her destination exhausted. She regarded her state of distress as completely neurotic. She decided not to give up her seat.” In the very next sentence, Dora stands up and offers an old woman her seat. The self-justification gives way to action, an action that reveals a side of the character she herself was unable to see and, thus, one she remains not fully capable of understanding.

Murdoch’s novels contain the satisfactions we often go to fiction to find—catharsis, memorable characters, entertaining stories, delightful sentences, vivid images—but they stop short at catering to a reader’s comfort. They thus provide two very different kinds of pleasure simultaneously. On the surface, they’re great fun to read. At the same time, Murdoch’s restraint, her refusal to flatter you with a judgment that mirrors your own previously held opinion, means the books also require that the reader bring herself to the text. We are not simply nodding audience members, but active participants in the reading process. A second version of the novel, one that is born of both the text and our own intelligence and sense of ethics, emerges as we read. This process doesn’t feel like work, even though our minds are firing a little hotter than they often do while reading. Instead, it feels deeply satisfying, and stimulating. It’s not a coincidence that every time I or one of my friends finishes a Murdoch novel, we immediately seek out someone else who has read the same book to talk about it. What we really want to do is compare our separate, private versions of the novel to one another’s, and marvel, once again, at how she pulled it all off.

In late 2020, Oxford Languages, keeper of the Oxford English Dictionary, released a report on the pandemic’s effect on English. Our vocabularies, it turned out, had changed dramatically. Suddenly we were all talking about “lockdown” and “flattening the curve,” and we coined new phrases like blursday and doomscroll. Together, these words paint a picture of our souls over the past few years: stuck in place, one day smudging into the next, constantly obsessing over our anxieties until we reach a state of anhedonic paralysis. Art can help us break out of this, but to do so it must resist both scrolling further into doom and providing easy answers.

Iris Murdoch knew this. “Only the very greatest art,” she wrote in “Against Dryness,” “invigorates without consoling, and defeats our attempts, in W.H. Auden’s words, to use it as a magic.” She might not believe in magic, but her provocative, singular, strange, and beautifully constructed books do cast a kind of spell, one that can help us recover a little bit of our souls at the exact moment it feels like everything around us is conspiring to render us numb.

No comments:

Post a Comment