Italo Calvino was born in Cuba in 1923 to Italian parents. He died in Italy in 1985.

I discovered Calvino’s work around 1988 at the University of Texas at Austin, in an English class called “Magic Realism,” which is as good of a label as any for his writing. I prefer “fantastic literature” or “fabulism,” but consider the terms broadly synonymous. We studied Calvino alongside the work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and other international authors.

At the Italian Cultural Institute of New York in 2017, commemorating Calvino’s Six Memos for the New Millennium, it was stated that “Italo Calvino is one of the few Italian writers of the late 20th century who was well known also outside Italy. And not only in the literary world. His fiction and non-fiction works — often not always easy to distinguish — inspired writers, architects, designers, philosophers, etcetera.”

Calvino’s Life

Calvino’s parents were botanists who did pioneering work cultivating previously exotic crops like grapefruit and avocado. Born in Cuba, his parents named him “Italo” so he would never forget he was Italian. Ironically, they wound up raising him in Italy anyway. He became self-conscious about his name because he thought it sounded “belligerently nationalist” – as if an American named “Americo” etc. So, it is doubly ironic that he is often cited as Italy’s greatest modern writer.

He was definitely not a nationalist. Witnessing the rise of Mussolini, Calvino evaded the draft, instead joining the Italian resistance (“the partisans”) hiding in the mountains. As a result, the Nazis kidnapped his parents and held them hostage for months. They even pretended to shoot his father in front of his mother three separate times, of which Calvino later wrote, “The historical events which mothers take part in acquire the greatness and invincibility of natural phenomena.”

In an autobiographical note in his book The Uses of Literature, Calvino wrote, “Having grown up in times of dictatorship, and being overtaken by total war when of military age, I still have the notion that to live in peace and freedom is a frail kind of good fortune that might be taken from me in an instant.” (This quote parallels a quote from J.G. Ballard, who was also swept up in World War II: “It held a deeper meaning for me, the sense that reality itself was a stage set that could be dismantled at any moment, and that no matter how magnificent anything appeared, it could be swept aside into the debris of the past.”)

On his personal life, Calvino was notoriously reticent to comment. Asked by an English interviewer for background information, he is said to have responded, “Oh, the English. You have an extraordinary genius for biography. For you the history of literature is a collection of books about the lives of people, while we Italians are more interested in ideas.”

Nevertheless, in The Uses of Literature, he wrote, “The ideal place for me is the one in which it is most natural to live as a foreigner. Therefore, Paris is the city where I found my wife [Chichita Singer, an Argentinian], set up home, and raised a daughter [Giovanna]. My wife is a foreigner, too, and when the three of us are together, we talk in three different languages.” Calvino lightheartedly elaborated about the young Giovanna in a 1972 letter to a friend: “She speaks three languages… and has no wish to learn to read or write.”

In 1985, the 61-year-old Calvino was preparing lectures to give at Harvard (Six Memos for the New Millennium) when he died of a stroke. His wife said he had planned to write 16 more books. She died that same year.

The Evolution of his Style

When the war ended, Calvino wrote the novel The Path to the Spider’s Nests, a fictionalization of his experiences in the resistance. It is not a great novel, but it is a good first novel from a young man. It is written in a “neo-realist” style, a style he later abandoned as he found his voice. In the introduction to The Path to the Spider’s Nests, Calvino’s recollections of the immediate post-war days include “a moral tension that was in the air, and a literary tendency which epitomized our generation immediately after the Second World War.” He speaks of an Italian “literary explosion” that was “not so much an artistic phenomenon, more a physical, existential, collective need …. The rebirth of freedom of speech manifested itself first and foremost in a craving to tell stories …. The greyness of everyday life seemed something that belonged to another epoch; we existed in a multi-colored world of stories.”

That young generation of new writers became known as the neo-realists, of whom Calvino says, “We were all content-driven, yet there were never such obsessive formalists as ourselves; we claimed to be a school of objective writers, but there were never such effusive lyricists as us … out of that naïve desire to create literature characteristic of a ‘school’.”

The novelist Cesare Pavese picked out an important element in Calvino’s writing which pointed the way to his future fabulist style. Calvino writes, “It was Pavese who was the first to talk of a fairy-tale tone in my writing. Up until then I had not been aware of this, but from that point onwards I became only too conscious of it, and tried to confirm that definition. The story of my literary career was already beginning to be mapped out.”

Calvino’s first couple of books were successful, but then his writing ground to a standstill as he wrestled with the question of style. Around 1950 he turned this around with a realization: “Instead of making myself write the book I ought to write, the novel that was expected of me, I conjured up the book I myself would have liked to read, the sort by an unknown writer, from another age and another country, discovered in an attic.” His style changed from neo-realist to fabulist, and his career took off again. He never looked back. At one early point he researched the oral tradition of Italian folk-tales, compiling hundreds from the work of folklorists. Then he omitted any which showed outside influence, for instance the Italian variant of “Snow White” features seven robbers; the notion of seven dwarves (Calvino suspected) was a Germanic one. He chose the 200 best, rewrote them for the general reader, and published them as the book Italian Folktales.

Calvino had already veered in this direction, but writing Italian Folktales undoubtedly was a learning experience, cementing his new style for the rest of his prolific career. Maria Popova (of Brain Pickings) has noted that Calvino tremendously admired Jorge Luis Borges; that makes sense since Borges is a master of the fabulist style – that writing which recalls fairy-tales, fables, and parables.

In Calvino’s case, his style is so much like Borges, that it has become Borges. I could say the same about Stanislaw Lem and his relation to Borges. The stories of the three writers share these qualities: 1.) Short or very short stories (a few pages long or less) exploring single ideas at the expense of character and setting. 2.) Logically constructed stories that almost mathematically convert ideas to their opposites, at the story level but also at the sentence level. 3.) A focus on infinities: in the world, the mind, everyday life – everything is related to the cosmos. 4.) Normally pretty funny.

Calvino (and Lem) expanded on Borges’ achievement: they took “fantastic literature” from the style of folk-tales and parables and applied it to science fiction. In Lem’s case, he wrote Borgesian science fiction and kind of had a superior air about it, including insulting Borges himself for not thinking of it first. In contrast, Calvino applied the Borgesian formula to more than one type of story: fantasy, science fiction, drama, love stories, etc.

Calvino’s science fiction stories may be found in the books Cosmicomics and t zero. It is as if they were written to satisfy a thought experiment, like all of his work. In this case the thought experiment is: what if you wrote fables to explain modern scientific knowledge? The result is a fable which could not have existed before the modern world. It is also a science fiction story which would not exist without the form of the fable. It’s such a preposterous idea that it can only be accomplished with a wink. For instance, the short story, “All at One Point” is about life in the singularity before the Big Bang, and how the creation of space came to be. It begins: “Naturally we were all there … where else could we have been? Nobody knew then that there could be space. Or time either. What use did we have for time, packed in there like sardines?”

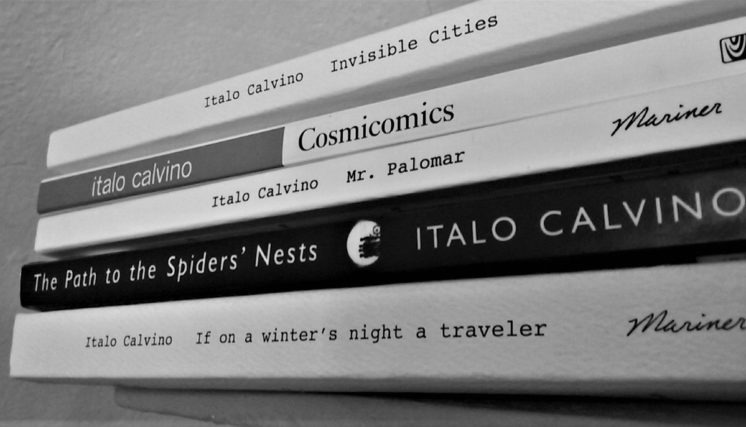

Another feature of Calvino’s work, shared by Lem and J.G. Ballard, is that of playing with story form, and inventing new forms. In Lem’s case, he developed the idea of writing reviews of, and introductions to, books which don’t exist. Ballard wrote “The Index,” an index to a book which does not exist. He also wrote “Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown,” a story one sentence long, but in which every word is heavily footnoted. While Calvino wrote If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, a novel consisting of the first chapters of novels that do not exist. And he also wrote Invisible Cities, a travelogue of non-existent cities. Cynically one might consider these new story forms as gimmicks; in my view they are evidence of raw creativity and outside-the-box thinking, from the kind of progressive genius that pushes the limits of imagination.

Invisible Cities

Invisible Cities, on some days, is my favorite book ever written. Jeanette Winterson called it, “the book I would choose as pillow and plate, alone on a desert island.” I could not agree more; I return to it again and again.

It is a trim little book. The language is economical, yet lyrical and poetic, and very visual. It is called a novel but really (like many Calvino novels) it’s a series of short vignettes, in this case each describing a conceptual city. There is no plot and therefore the vignettes may be read in any order. There are also no characters besides the cities themselves. That is not quite true; the unifying idea is that Marco Polo is describing his travels to the Emperor Kublai Khan, and they have little philosophical dialogues sprinkled throughout about cities, perception, and the nature of reality. But these provide only the loosest of structure between vignettes, which easily stand alone as one-offs. The book is a philosophical work more than anything, but it is not difficult reading. Each fantasy city embodies some concept, or truth, or contradiction, which is then explored to its logical extreme. It is a travel journal through Calvino’s poetic imagination, a map of the mind. Although each describes a place that does not exist, one recognizes pieces of one’s own city throughout. Along the way you question who you are, your place in the world, and the degree to which perception is a mental construct. It may be read like a book of Zen koans, or philosophical aphorisms. Each suggests a new way of seeing, and of being. This book transports the reader like no other I have read. My copy is always close at hand; I will pick it up and read one at random, and then put it down again and think about it all day.

A game I play with myself is to imagine that historians of the future, sifting fragmentary ruins of our civilization, find a copy of Invisible Cities. But it is damaged and the author’s name cannot be determined. They analyze the text, and with their fragmentary knowledge of the literature of our time, these future literary detectives determine that it could have been written by any of the writers I have profiled in this series.

William S. Burroughs could have written it because he has a history of writing about fictional cities, “Interzone” being the most well-known, but also “The Composite City” which he hallucinated on yage. Detailed over several pages in The Yage Letters, Burroughs describes it as a place “where all human potentials are spread out in a vast silent market.” So it is tempting to ascribe Invisible Cities to Burroughs, but stylistically it doesn’t match his prose. Burroughs was not as lyrical. J.G. Ballard could also have written it, master as he was of visualizing imaginary spaces connected to infinities (“The Infinite Space,” “Report on an Unidentified Space Station”). And Ballard was a lyrical writer. However Invisible Cities fails to include many of Ballard’s standard obsessions, for instance: madness, murder, and transgressive sex acts. So Ballard is eliminated as a possibility. Next Stanislaw Lem is examined as a possibility, and at first this seems very promising. Lem is certainly inventive enough, and his stories have that fairy-tale feeling that is an essential ingredient. He can even be lyrical, however, ultimately it is decided that Lem’s prose contains a cutting edge of cynicism that disqualifies him from consideration — Invisible Cities does not bear a trace of cynicism. Then the possible authorship of Jorge Luis Borges is investigated. The future historians find Borges to be the perfect candidate, and mis-attribute authorship of Invisible Cities to him. It seems like a match. As I said above, Calvino’s style is so much like Borges that he became Borges. Borges is fabulist, lyrical, inventive, sprinkles his work with infinities, and is driven to explore ideas as opposed to characterizations – so a book essentially without characters could easily be one of his.

But then one of the historians notes the one feature that disqualifies Borges, and that is the length of the work. A short work to be sure, but Borges almost exclusively wrote short stories. And although Invisible Cities can be considered a collection of short pieces, they hang together and focus on shared themes. This is what makes Invisible Cities a novel – albeit a strange one – and Borges simply did not write novels, even strange ones. Whereas Calvino wrote almost nothing but strange little novels, built of shorter pieces, but buttressing each other’s themes as a novel’s chapters do. The only author who could have possibly written Invisible Cities is Italo Calvino, the Italian fascist-fighter with the belligerently nationalist name.

No comments:

Post a Comment