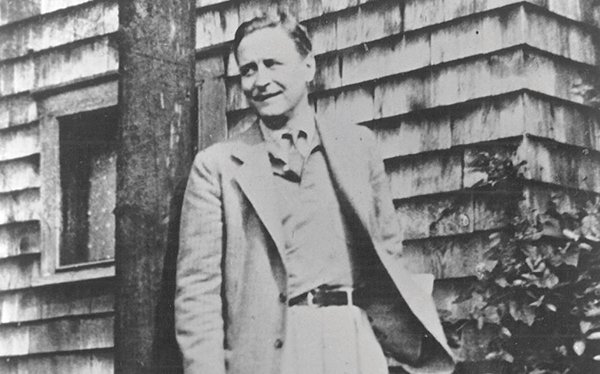

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Asheville Days

by Ray Hardee

May 2, 1989

By the time F. Scott Fitzgerald and his troubled wife Zelda reached Asheville in 1935, they were already in a period of serious decline. And not even the good mountain air nor the gentle setting at the Grove Park Inn could do much to change their fortunes.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was not without problems during his 1935 stay in Asheville's Grove Park Inn. His wife Zelda was seriously ill. A victim of schizophrenia, he had suffered two severe breakdowns and was not improving. His novel “Tender is The Night,” published in 1935, had received bad reviews, and sales were poor. His debts were great, and his drinking problem was awful. There were long periods when he could not control his nerves or concentrate on his writing. He longed for the good days of the 1920s when Zelda had her health and they were living on the French Riviera in luxury and he was receiving fame and fortune from his novels. He was to discover that he could never return to this life again.

Fitzgerald went to Asheville to look for a place of anonymity, a place to collect his thoughts. He had driven south from Baltimore almost aimlessly, stopping first at Hendersonville and Tryon, and then Asheville. He suggested to friends that he picked Asheville for treatment of a "mild case" of tuberculosis. This was more fiction than fact. He had suffered a bad siege of the flu, but his real problem was alcoholism.

William Johnson remembers his father Ulysses Johnson speaking of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Ulysses Johnson was the bell captain at Grove Park Inn while Fitzgerald was there.

"Fitzgerald was very courteous,” Johnson says. "He autographed some books for my father.”

Fitzgerald always stayed in the same suite of rooms at the Grove Park Inn, numbers 441 and 443. One housekeeper remembers a co-worker taking out baskets full of typed paper daily while cleaning the suite. She was also taking out a lot of empty beer bottles.

Tony Buttitta, who wrote “After the Good Gay Times" (Viking Press, 1974), recounts some of Fitzgerald 's experiences in Asheville in the summer of 1935. Buttitta operated a small bookstore in the old George Vanderbilt Hotel where he first met Fitzgerald. They became more than acquaintances but less than good friends. Fitzgerald needed someone to talk to–a sounding board. Buttitta, a struggling young writer, was impressed with Fitzgerald, and very honest with him in their discussions.

Fitzgerald had an affair with a wealthy married woman who was staying at the Grove Park Inn. He called her Rosemary (not her true name) after the character Rosemary Hoyt in “Tender is The Night.” Rosemary had come to Asheville with her sister, who had a nervous condition. Rosemary, whose husband had remained at their home in Memphis, was prepared to leave her husband for Fitzgerald. She offered to pay Fitzgerald’s expenses for his wife Zelda and his daughter. Fitzgerald was attracted to Rosemary but realized that the situation could not endure. However, he could not break off the affair. This was done for him by Rosemary's sister, who had confronted Rosemary and told her if she did not break off the affair she would tell her husband.

During all of these events, Fitzgerald was trying to put his writing career back together. He was writing magazine articles which were mostly rejected. He would commit himself to write and then say that he needed alcohol for inspiration, claiming that his writing was sterile and flat if he wrote sober. But then he would get drunk and not write anything. After a binge of heavy drinking, Fitzgerald would go on the wagon. He would replace the whiskey with beer and sometimes he would replace the beer with Coke or black coffee. Usually he stayed with beer, which he consumed in amounts of up to 30 bottles a day.

Fitzgerald felt that his stories were out of style. His novels represented the jazz age. Critics were calling his work trivial and immature. During the 1930s the novel for the working class (proletariat) was being praised. Fitzgerald felt that he was out of step with this genre and was frustrated. Tony Buttitta tried to assure Fitzgerald that his novels were not dated, but that they would endure the test of time the same as the works of Faulkner and Wolfe.

Fitzgerald did not see Thomas Wolfe while he was in Asheville but had met him earlier in Paris. He felt that Wolfe's talent was tremendous. He met Wolfe's mother incognito at the Old Kentucky Home. Mrs. Julia Wolfe had dominated the conversation and said that she didn't rent rooms to drunks. He really hadn't wanted to rent a room, but just to see the place. He felt sorry for Tom having to endure Mrs. Wolfe in his childhood.

Fitzgerald asked Tony Buttitta to check out Highland Hospital to see if it would be suitable for Zelda. At this time Zelda was in an institution in Baltimore. Fitzgerald took Zelda to Highland in 1936 where she stayed for several intervals until her death there in a fire in 1948.

Mrs. Laura Guthrie Hearne wrote a daily journal on Fitzgerald's activities in Asheville from June through September,1935. Her diary is now a permanent part of the F. Scott Fitzgerald memorabilia at Princeton University.

Mrs. Hearne, a graduate of the School of Journalism at Columbia University, went to Asheville from New York in 1932 for her health. Her doctor in Asheville advised her to stay as long as she could, so she began telling fortunes at Grove Park Inn to help pay some of her expenses. She lived in a small garage apartment just off of Macon Avenue near Grove Park Inn. The hostess at Grove Park Inn would notify Mrs. Hearne when different groups and conventions were arriving. Mrs. Hearne wore a gypsy costume and she would read the palms of the guests and predict their fortunes. It was more of a diversion for entertainment for the guests than anything serious.

Mrs. Hearne first met Scott Fitzgerald in June 1935 at Grove Park Inn. She had been telling the fortunes of some members of a hairdressers' convention. The hostess introduced Mrs. Hearne to Fitzgerald and asked her to read his hands. They became good friends and she worked as his secretary while he was in Asheville that summer.

Fitzgerald initiated an innocent flirtation with Mrs. Hearne. Although Mrs. Hearne may have been attracted to Fitzgerald, she would not respond to any situation that was less than honorable. She was very much a lady and because of this she gained Fitzgerald's respect and confidence.

Her journal corroborated the affair of Fitzgerald and Rosemary. She referred to Rosemary as Gloria Dart (again, not her true name). Mrs. Hearne obviously did not approve of the affair, but she did not condemn Fitzgerald. She was fatalistic about the event and commiserated with Fitzgerald when he wanted to talk about it.

She asked Fitzgerald how many drafts he wrote of his novels. He replied that he always wrote four revisions. She asked what advice he would give to writers, and Fitzgerald said the first thing to do was learn to listen. In writing, he said to, "state the problem, don't solve it . . . be natural . . . be yourself.”

Zelda was the one true love of F. Scott Fitzgerald's life. He had loved her with an almost unselfish devotion. Zelda's affair with a French aviator while they were living on the Riviera in the 1920s was the beginning of their estrangement. Fitzgerald could never quite resolve himself to this event.

Their life together had been happy in many ways prior to her illness. Fitzgerald told Laura Hearne that in 1929 he and Zelda, dressed in evening clothes, had leaped off the balcony of a French restaurant into a pool. They went to a lot of parties and raised a lot of hell in typical college sophomore tradition. They enjoyed life completely in their own reckless manner. They drank too much. They truly loved one another.

Zelda told Scott that she hoped never to become ambitious. He felt that once Zelda committed herself to something, she would be possessed to master it. Fitzgerald said that he had chided Zelda on occasions for her indolence. He was to regret this later–saying he had pushed her into something she could not accomplish.

Zelda decided to study ballet at the age of 27. Fitzgerald did not discourage her at first, but when he realized that she intended to become a star of the first rank he tried to explain how difficult it would be for her. She was consumed with her ambition to become a dancer. She worked feverishly at training until she had her first anxiety attack and the beginning of her illness.

Fitzgerald referred to Zelda as "my invalid" with a tender affection. He told Tony Buttitta that Zelda was only a ghost of what she had been. His concerns about her apparently contributed to his drinking problem.

In Asheville he had pressure to continue his work in order to meet expenses. He was slowly beginning to believe that he could continue his writing, that he still retained his talent and it was secure. Writing was the one thing that he did know: he was a professional.

Towards the end of 1935, Fitzgerald had gained some control of his drinking and his writing improved. He sold three articles which appeared in the February, March and April 1936 issues of Esquire. These were an account of his near breakdown in 1935. He also published "Image on the Heart" in McCall's in 1936–an account of Zelda and the French aviator.

Asheville had been a place of solace for a troubled F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1935. He could never go home again to his old lifestyle, but he did go home to a new realization of his writing talent.

Ray Hardee, a native of West North Carolina, has a B.A. in literature from UNC Asheville. This is his first piece for Blue Ridge Country.

From The Archives: This article originally appeared in the May/June 1989 issue of Blue Ridge Country.

No comments:

Post a Comment