|

| Anita Loos |

Anita Loos – sharp, shameless humour of the 'world's most brilliant woman'

The writer of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was an extraordinary, barbed genius of the silent era, Hollywood and Broadway

Pamela Hutchinson

Monday 16 January 2016

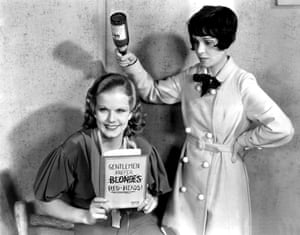

Piquant wit … the screenwriter and novelist Anita Loos.

Anita Loos, the screenwriter and author, claimed – in typically waggish style – to be furious at the women’s lib movement. “They keep getting up on soapboxes and proclaiming that women are brighter than men,” she said. “That’s true, but it should be kept very quiet or it ruins the whole racket.” Loos was a veteran of silent-era Hollywood, when women worked at all levels of the film industry – directing, editing, producing and designing. Scriptwriting, Loos’s forte, was the most feminine department: a “manless Eden” of female screenplay writers, scenario authors, story editors, intertitle artists and “script girls”. Loos may not have been the most successful screenwriter during Hollywood’s silent years (that honour falls to Frances Marion), but she was one of its greatest wits, most popular characters and one of its key storytellers.

Anita Loos, the screenwriter and author, claimed – in typically waggish style – to be furious at the women’s lib movement. “They keep getting up on soapboxes and proclaiming that women are brighter than men,” she said. “That’s true, but it should be kept very quiet or it ruins the whole racket.” Loos was a veteran of silent-era Hollywood, when women worked at all levels of the film industry – directing, editing, producing and designing. Scriptwriting, Loos’s forte, was the most feminine department: a “manless Eden” of female screenplay writers, scenario authors, story editors, intertitle artists and “script girls”. Loos may not have been the most successful screenwriter during Hollywood’s silent years (that honour falls to Frances Marion), but she was one of its greatest wits, most popular characters and one of its key storytellers.

Loos is best known today for her wickedly funny novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, written during her Hollywood years, which follows the escapades of gold-digging, flaxen-haired showgirl Lorelei Lee and her man-mad brunette chum Dorothy. For many, this breathless novel epitomises the highs and the lows of the jazz age, though it’s now most famous in its 1953 musical film incarnation starring Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell.

The book is typical of Loos’s sharp and shameless humour: for all that Lorelei appears to be a mercenary and a “dumb blonde”, the real butts of the joke are the men who fall for her charms. Loos was inspired to write it when she saw her friend, the literary critic and satirist HL Mencken, lose his cool when faced with a blond beauty.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes had been filmed before the musical, in 1928, when its roaring 20s satire would have been even more pointed. Loos, by then a fixture at Paramount, wrote the screenplay (with her husband, John Emerson) and the intertitles (with Herman Mankiewicz, who would go on to write Citizen Kane).

The 1928 Gentlemen Prefer Blondes had impeccable comic credentials, being directed by Keystone alumnus Mal St Clair, and starring two more former employees of Mack Sennett: Ruth Taylor and Ford Sterling. Alice White picked up the part of sidekick Dorothy after Loos nixed the studio’s original, and intriguing, choice of Louise Brooks. Brooks is said to have given a joyless performance in her screen test (“I stunk”), and Loos dismissed her, with an offensive turn of phrase that was, sadly, characteristic, saying: “If I ever write a part for a cigar-store Indian, you will get it.” The film was something of a flop, and we may never get to judge it for ourselves as it has long been considered lost.

But Loos’s Hollywood story began more than a decade before Lorelei first shimmied on to the pages of Harper’s magazine, where her novel was originally serialised. As a young woman in California, Loos was an avid moviegoer, long before a trip to the nickelodeon was considered a cultural event. She had strong opinions about which films were better than others and fancied that she could make a fair fist of writing movies herself.

Aged 24, she posted a short film scenario she had written to DW Griffith’s Biograph studio in New York. Not only did Griffith like The New York Hat, and pay her $25 for it, but the film he made from her story is one of his finest short features. Twenty-year-old Mary Pickford gives a typically nuanced performance in the lead role of a motherless child swept up in small-town scandal, and Lionel Barrymore makes his first screen performance as the local minister whose kindness causes the disgrace. By most people’s standards, The New York Hat would be precocious, but the vain Loos so often embroidered the truth that, in the telling of this story, she often claimed to have attained her movie debut as a teenager, even as young as 12 years old. Loos told some of the finest and funniest stories about Hollywood, but many should be taken with a sprinkling of salt.

The New York Hat (1912)

Loos wrote many more scenarios for Griffith, posting them from her home in San Diego, where she lived with her mother. Some of them he used, but many he considered unfilmable as silent pictures. “The laughs were all in the lines,” he complained, “there was no way to get them on to the screen.” For that very reason, he gave Loos the prestigious job of writing the intertitles for his epic Intolerance (1916), a vast portmanteau film taking in a contemporary crime drama, the fall of the Babylonian empire, a Bible story and the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572.

Loos’s amusing, compact intertitles leaven the film’s heavy material with crisp dramatic statements and comical jibes such as: “When women cease to attract men they often turn to Reform as a second choice.” Loos had found an excellent way to exploit her natural skill with a one-liner. A year later, Photoplay reported that Griffith had called her “The most brilliant woman in the world”, and praised her skilful writing, saying: “The most important service that Anita Loos has so far rendered the screen is the elevation of the subcaption [sic], first to sanity then to dignity and brilliance combined.”

Loos became renowned for her cleverness at writing piquant intertitles, first for a series of Douglas Fairbanks’s early films: her verbal wit a match for his physical gags. Four feet 11in tall, with a chic, gamine hairdo and a terribly expensive wardrobe, Loos was a distinctive presence and soon became as famous as many a movie star: the “soubrette of satire”. She had a collaborator by this time, the director John Emerson, to whom she was devoted and would later marry, although he was a notorious philanderer and far from her intellectual equal. Loos and Emerson worked as a writer-director team for many years. Emerson often insisted on taking a screenwriting credit when the words were Loos’s alone, and there have even been some controversial suggestions that when Emerson was indisposed, Loos took his place behind the camera. When they worked in New York, they stayed at the Algonquin hotel, where Loos was friendly with, though not an insider in, Dorothy Parker’s famous Round Table.

Loos spent years as a successful Hollywood screenwriter, at Paramount, United Artists and MGM. She developed a knack for talent spotting, and moved happily into sound films, not least because the witticisms that were confined to titlecards in her silent movies found a home in fast-talking screenplays of the 30s. Fashion-obsessed, gossipy and loyal, she forged last Hollywood friendships with a number of stars, included those she “spotted”, from the Talmadge sisters (she wrote a very affectionate biography of them), to Jean Harlow and Paulette Goddard. When Emerson’s health failed in 1937, she discovered that he had frittered away much of their income and requested a divorce, realising that after all she would have to make a success of her career alone. And she did.

Loos died in her 90s, in 1981. Her legacy comprises a vast body of silent work, as well as sound-era successes including the sizzling pre-code flick Red-Headed Woman (1932), starring Jean Harlow, and the breakneck cattiness of The Women (1939). She also adapted her Gentlemen Prefer Blondes for a triumphant Broadway musical production starring Carol Channing in 1949, and two years later made a New York sensation of Colette’s Gigi, which ran for more than a year, with a young Audrey Hepburn in the lead role.

Much of Loos’s writing success came from the fact that she was a born raconteur, the life and soul of many a Hollywood party, with a hawkish eye on the glamorous, or scandalous, events that surrounded her. Hence the pinpoint satire of Lorelei Lee. In one of her biographical volumes, A Girl Like I, Loos wrote that: “I’ve enjoyed my happiest moments when trailing a Mainbocher evening gown across the sawdust-covered floor of a saloon.” Those Hollywood memoirs, while not always to be trusted, are among the most entertaining ever written, because Loos remains great company, and because her story proves how far a young woman in a young industry could get on brains and high spirits alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment