Ian McEwan: ‘I’m going to get such a kicking’

Decca Aitkenhead

Sometimes, Ian McEwan wonders if he will be shot. He pictures the scene at a public book signing. “Someone’s going to come up, especially in the States, shooting at my chest, you know. It would be quite easy. It has often crossed my mind, especially after there’s been some kind of mass shooting.”

Has he ever had cause for alarm? “Occasionally someone comes towards me and I think, uh-oh, where’s the guard? Some glowering, frowning guy who’s somewhat overweight shambles up to the table, and you think, yes, he’s got something on his mind.” And? He smiles. “And he turns out to be utterly charming. Yes, so I always get those wrong.”

McEwan’s other worry about doing a book tour is that he will end up repeating himself. “I start out all right. But then you get a bit tired of your own voice. And then this feeling begins to creep in. You begin to feel a bit like a sort of brush salesman of old, selling encyclopedias or double glazing. It’s a sort of feeling of repeating yourself, and disliking yourself for it. It’s a certain kind of self-loathing.”I hadn’t imagined him prone to self-loathing. “I’m not generally,” he agrees, and begins to chuckle. “We made up a medical syndrome, [my wife] Annalena and I, for people who are too bumptious and fond of themselves. It was called Self-loathing Deficiency Complex.”

Nutshell is McEwan’s 17th book, in a career that is practically a publishing industry all of its own. He is the leading light today in a circle of friends (Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie, the late Christopher Hitchens) whose early promise in the 1970s established their reputation as Britain’s golden generation of writers. To many fans they remain, to this day, literary royalty. To their critics they became a smug, misogynistic clique with a bad case, you might say, of Self-loathing Deficiency Complex.I’d wondered which version I would find. The fastidious figure I meet in a discreet London hotel is polite and rather formal at first, but soon relaxes into gentle self-deprecation, and is the only person I have ever known to interrupt one of his own anecdotes to ask, “Is this interesting?” There is no particular need for him to keep mentioning Annalena, but he does, and each time makes me like him more. At one point he observes, “Without women readers the novel would be dead,” but it is perfectly obvious that economic self-interest is not why he has no problem with women. If McEwan has a prejudice against anyone, I think it may be against men – or, rather, a certain type of man. The first glimpse comes in an anecdote he tells with evident pleasure, about what happened when he once tried to give away unwanted books to strangers in a park.

“The women were all, ‘Oh lovely, thank you.’ And the men were,” he adopts a lumpen cockney accent, ‘Nah, you’re all right, mate. Nah, sorry mate, nah.’” He laughs in wonderment. “Not one book.”More than one of McEwan’s earlier novels features an uneducated but dangerously virile man (Tarpin in Solar, Jed Parry in Enduring Love)who imperils the comfortable middle-class world of an intellectually highbrow fellow. In his new book – a short, crisp work of 199 pages – we meet a sweet-natured, romantically minded but fatally passive poetry publisher called John, married to a beautiful young wife called Trudy, who is heavily pregnant with his child and having an affair with his boorishly unsophisticated but sexually irresistible brother Claude. The adulterous pair conspire to murder John and inherit the £7m marital home, in a plot that borrows heavily from Hamlet and Macbeth – save for one radical innovation. The story is narrated by the foetus inside Trudy’s womb.

To McEwan’s knowledge, no story has ever been written from the perspective of a foetus before. “And yet it seemed obvious once I started it.” The idea came to him one day from nowhere, while he was daydreaming. “Suddenly there appeared before me the opening sentence of the novel, which I don’t think I’ve changed, apart from adding ‘So’ in front of it: ‘So, here I am upside down in a woman.’ I thought, who on Earth would say such a thing? Then I immediately thought it would be a lovely rhetorical challenge to write a novel from the point of view of a foetus. The idea struck me as so silly that I just couldn’t resist it.”

The only person he could think of who was more helpless than a foetus was Hamlet (“able to think a lot, but trapped”) which gave McEwan his plot. He solved the problem of how a foetus could know enough about the outside world to make sense of what he overheard by making Trudy an avid listener to Radio 4 and podcasts. “But really, once you start asking one question, you think, well how did he get all this grammar? Who’s he talking to? Where’s his computer?” McEwan breaks off into laughter.

“I said to Annalena, ‘I might have to go abroad when this is published, far away.’ I just thought, I’m going to get such a kicking for this. But, the more I thought that, the more I enjoyed it. I was committed from the first sentence. I just had so much fun. I’ve written novel after novel rooted in a shared and plausible world. I have researched novels, and I’m very committed to a form of social realism, so this was like a holiday of the senses. I didn’t have to research a thing.”

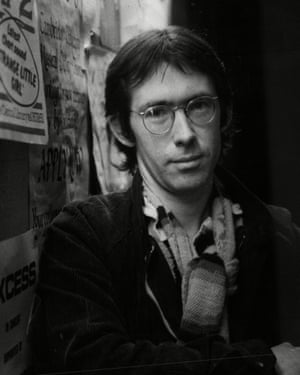

McEwan in Cambridge in 1980.The research McEwan undertakes is legendary. He spent two years shadowing a neurosurgeon for the novel Saturday, and had the Centre for Quantum Computation at the University of Cambridge check his physics in Solar. In fact, the novelist is so famous for his research that everyone always assumes he is gathering material, “even when I’m just having dinner”, and are “crushed and disappointed” to be told he isn’t, so these days he finds it easier just to say he is. Personally, I find the research distractingly clunky, and feel Nutshell is all the better for its absence. But I’m charmed to learn that he keeps an archive of all the letters readers write, alerting him pedantically to some obscure error or other… “Oh yes, I love that.” He always writes back and thanks them, and corrects the mistake in future editions. When I suggest he won’t be getting any letters like that about Nutshell, he looks doubtful. “Oh yes, I may get a letter from someone saying, ‘Excuse me, those foetuses can’t say a word.’”

McEwan’s work is a staple fixture of the English A-level syllabus, but “Nutshell won’t make it,” he grins, “because all those speculations from my narrator about what it means to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your face.” If students were asked for an explanation of what the novel is about, however, what would it be? “You mean is there a hidden message in there for us? Well, I hope it’s about the communication of pleasure, which is not sufficiently discussed, I think, nor sufficiently central to the way we talk about books.” I assume he is making some complicated subtextual reference, until he explains that the only real point of this book is to bring pleasure to its reader. “My best hope for it would be that. That’s its key.”

I had flattered myself that I’d found its purpose buried in a chapter towards the end, when Trudy rids herself of the disagreeable sensation of guilt by deciding that as she never really meant to do anything bad, that meant that she hadn’t, and therefore everything must logically be Claude’s fault. This leads into a dissertation on the contemporary trend for any dimension of identity – race, gender – to be reclassified as a matter of personal choice, determined not by objective facts but an individual’s feelings. From there the chapter goes on to marvel at university campuses where “trigger warnings” must be issued to protect students from any information they might conceivably find distressing, and any speaker wishing to express an opinion its audience might not share must be no-platformed. From all this, I infer that Nutshell is really an allegorical indictment of our post-factual age, in which feelings matter more than the truth.

I’m rather impressed by McEwan’s nerve, given all the trouble he got into earlier this year when he told an audience, “Call me old-fashioned, but most people with a penis are men.” The transgender community erupted in fury, and McEwan had to issue a public apology. “I might as well have said, ‘Hitler was right’, for the storm I got into,” he remarks ruefully.

This may or may not explain why, in Nutshell, “I have my foetus say how very disappointing [that] there are only two options here, pink or blue as it were.” But McEwan takes care to explain that he has no problem with gender reassignment. “What does it matter to me if people’s identity suddenly finds new routes to express itself? Where I get a little critical of it is where selfhood becomes all of your politics, in a world in which we are more troubled than at any point I can remember in my adult life.”

Do identity politics look like decadent narcissism to him? “It feels like that, coming to the university aspect of it. These children have grown up in an era of peace and plenty, and nothing much to worry about, so into that space comes this sort of resurgence that the campus politics is all about you, not about income inequality, nuclear weapons, climate change, all the other things you think students might address, the fate of your fellow humans, migrants drowning at sea. All of those things that might concern the young are lost to a wish for authority to bless them,” he says, “rather than to challenge authority.”

There is another possible interpretation of Nutshell, one I venture somewhat tentatively. In 2002 McEwan discovered that he had an older brother, born out of wedlock when his parents had a wartime affair while his mother was married to someone else, and given up for adoption. Their mother’s husband subsequently died in battle, McEwan’s parents married, and by the time McEwan met his brother, a bricklayer, their father had died and their mother was in the late stages of dementia. Has McEwan anticipated, I ask, that some people may see parallels between McEwan and Nutshell’s cultured poet, John, and wonder if there is anything of McEwan’s brother, David, in Claude – who covets the woman and the wealth which is rightfully John’s.

“I hadn’t thought of that.” McEwan looks surprised, and considers it in silence. “I mean, I can’t go anywhere with that. It never crossed my mind, and it would be quite a perverse reading, I think.” Fearing he will take offence, I apologise for the impertinence of the question, before asking if his mother’s estate was shared with David, but he doesn’t appear to mind at all. “Yes, yes, but there was hardly any estate.”

Prior to David’s appearance, McEwan’s personal life had been broadly unexceptional. The apparently only child of a not very happily married Scottish sergeant major and English housewife, he spent his early childhood in east Asia and north Africa, and his adolescence at a state boarding grammar school. After studying English at Sussex University he became an early graduate of Malcolm Bradbury’s creative writing course at the University of East Anglia, where he met his first wife, Penny Allen. The couple lived in London and had two sons, but divorced in 1995; unusually for the time, the sons stayed with their father, and two years later he married Annalena McAfee, then a Financial Times arts journalist he met when she came to interview him. They split their time between a Bloomsbury flat and a country home in Gloucestershire.

I’m curious to know if he feels a sense of fraternal connection with his unexpected brother.

“I do, but it’s a bit abstract when you haven’t grown up together. I spoke to him yesterday and we had a long chat on the phone.” He pauses for a moment to think. “Well, I wouldn’t be doing this with another bricklayer from Wallingford.”

Which brings us to the aspect of McEwan’s work some readers, myself included, find troubling. The uneducated men of his novels often portray a caricature of menacing masculinity – not unlike, in fact, the “frowning, glowering, somewhat overweight” gunman he dreads appearing in a book signing queue to shoot him. The contempt and fear with which he can seem to regard men less educated than himself – men who say “Nah, mate” when offered a free book – makes me wonder how many he actually knows.

“Fewer and fewer. Like, I knew so few people who wanted to leave the EU. I just love ideas and I love reading books and I live in a world of constant curiosity about ideas, so my characters tend to be people who are like that on the whole. Not all characters, but on the whole that’s what I am. And I think that you just have to pursue your interests. My interests are generally having articulate characters, because I can explore the things that I’m interested in, that’s all.”

Does he ever worry that he comes across as a snob?

“Well. There’s always this word ‘elitism’. I think that elitism means having read some books, which I can’t possibly see as elitism… this is one of life’s pleasures. I don’t go to football matches. People I know do get enormous pleasure from them; I wouldn’t think of them as elitists. We seek our pleasures in accordance with our personalities and backgrounds. I came from a very unlettered home, which meant that my adolescence – fortunately, I think, as I look back on this now – was about all the things the friends I then got to know at university couldn’t bear. Their mum played the harpsichord, or their dad was a well-known philosopher. I was running towards these harpsichords. They for me were the light, so I haven’t really changed from that, so there are some advantages in not having a book-filled, classical music-filled home which you have to rebel against. So my rebellion was to go to all these new places where no one in my family ever trod, and I haven’t really stopped.” His parents had been working class, as are all of his aunts and uncles, “But I probably don’t know them well enough to write novels about them. I could do it, but what it’s like to be a manual labourer just doesn’t interest me enough. That’s the problem.”

He expects reviews of Nutshell to be “wildly varied”, but says he’s so used to no critical consensus that he no longer reads reviews. Annalena provides edited summaries instead, but the wild divergence of opinion can be “hilarious”. Solar, for example, enjoyed “fairly good” reviews in the UK, but “In the States it was disastrous. It was just unbelievable. I remember sitting on the edge of a hotel bed with Annalena, and she said, ‘Well, I advise you not to read the Boston Globe, or the New York Times, or the Washington Post. And don’t go anywhere near the Chicago Tribune, and stay away from the LA Times and the San Francisco Chronicle’.” The only newspaper she advised him to read, he laughs, was the Modesto Bee. Modesto is a small city in central California.

I’m not entirely convinced by McEwan’s tendency to declare any slight “hilarious”. For example, “I saw this phrase and had to turn my head away, but again it made me smile. Some troll-like person on The Spectator wrote that The Children Act was ‘unforgivably bad’. When I told Julian Barnes, he fell about laughing. I mean, how bad can I get?”

Moments later he offers a more convincing response. “‘Unforgivably bad?’ Well, fuck you.”

If not critical acclaim, for what then does he now write? “Ah, the dopamine moment is finishing them. It’s, you know, when you’re thinking you’ve got it to where you wanted it to be.” What about sales? “No. I don’t care about sales. I mean, it’s nice to have them. I wouldn’t go looking for low sales, but no.” His books still earn back their advance, but nowadays this can take five to 10 years, and he doesn’t mind if they don’t. “I don’t think The Innocent did, actually… ever.” He always knows a chair of an event has consulted Wikipedia when he is introduced with “the same sentences I hear all the time, remarking on my colossal sales. And it’s just not the case. That’s not it.” It only says so on Wikipedia, he assumes, because, “I think they’re talking about Atonement [which was adapted by Joe Wright into an Oscar-winning film in 2007]. Which was a dreamy experience. But I’ve never had it again since on anything like that scale.” Does he think he may yet write his best novel? He gives a wan smile. “That’s a really good question, because recognising the moment when you won’t is really difficult, and sad. There’s that often-used trope, ‘His best work is behind him.’” He cites it with a sadness that makes me wonder if it haunts him.

“Yes. Inevitably, you’re going to get less word rich, less thought rich. You’re not as clever as you were when you were 38.” But he hopes the trope doesn’t yet apply to him. “I just don’t know when I reach that point. I mean, at some point you’re going to reach it. Even if your best novel was your last one, you don’t know of course it’s your last one.”

Would he stop writing if he did? “That’s what I wonder about. It’s a bit like politicians; it always ends in tears. They never know when to get out.” Would he? “Well if I was Federer now, I’d stop.” He pauses. “It’s a question I can’t answer, but it’s painful to contemplate that you reach that moment when it’s just one long decline.” How would he know when he had? “Exactly. I don’t know how I’d know.”

I wonder if, at 68, he feels his generation of writers fulfilled their golden promise. The predictions of dazzling genius were never, he points out, made by them, least of all by himself. “But I think that, if you were to stack up all the novels, I think it’s a really substantial volume of work. Yes. But we made no claims. And we’re not dead yet.”

• This article was amended on 27 August 2016. Ian McEwan mistakenly said Modesto was a little town in southern California. This has been corrected.

No comments:

Post a Comment