The 100 best nonfiction books: No 32 – The Last Days of Hitler by Hugh Trevor-Roper (1947)

The historian’s vivid, terrifying account of the Führer’s demise, based on his postwar work for British intelligence, remains unsurpassed

Monday 5 September 2016

“Now that the new order is past, and the thousand-year reich has crumbled in a decade, we are able at last, picking among the still smoking rubble, to discover the truth about that fantastic and tragical episode.” Some books simply exude excitement and self-confidence, as if the writer is on fire with ideas, or intoxicated with information. This is one of those titles.

From his commanding opening sentence, the author of this engrossing forensic masterpiece, a work of brilliant reportage, knows that the story he is about to unfold will be unputdownable, a scoop of historic proportions: history in the making. That, as we shall see, would come to haunt him at the end of a long and distinguished career.

In 1945, Hugh Trevor-Roper was a 31-year-old British intelligence officer, an academic historian who had been recruited to Bletchley Park to fight the secret war against the Nazis. When hostilities ended, Trevor-Roper found himself in occupied Germany. He was appointed by Dick White, then head of counterintelligence in the British zone, to find out what had happened to Hitler. The Nazi leader had, by then, been missing for more than four months since Germany’s unconditional surrender on 7 May, becoming the subject of many bizarre and outlandish rumours inimical to a secure postwar settlement.

Trevor-Roper, working under the pseudonym of “Major Oughton”, completed his report in record time. “The British Intelligence Report on the Death of Hitler” was delivered to the four-power intelligence committee in Berlin on 1 November 1945. To his credit, Dick White saw that there might be a book in it, and persuaded his protege to undertake a revision of his material once his official duties were over. The outcome of one spy’s intuition about a gifted subordinate, The Last Days of Hitler was published in March 1947 and became an immediate bestseller.

Trevor-Roper’s contemporary and rival, the historian AJP Taylor, later wrote in the Observer: “Trevor-Roper’s brilliant book demonstrated how a great historian can arrive at the truth even when much of the evidence is lacking or, as in this case, deliberately kept from him… This was all the doing of one incomparable scholar.”

The remarkable luxury Trevor-Roper enjoyed as an investigative historian was that most of his informants were still available for interview. The stage was set for an enthralling quest into the heart of darkness, the smouldering ruins of the postwar Reich, a plot worthy of any thriller.

Trevor-Roper’s narrative starts with a long scene-setter, describing Hitler, his court and the “vast system of bestial Nordic nonsense” with which the Nazi high command was obsessed. Goering, Speer, Himmler and Goebbels are memorably depicted with a rhetorical zest inspired by Trevor-Roper’s admiration for great British historians such as Gibbon and Macaulay. Himmler, for instance, becomes “an inexorable monster whose cold, malignant rage no prayers, no human sacrifices can ever for one moment appease”.

In resonant periods, Trevor-Roper establishes how, after the failure of the bomb plot of 20 July 1944, the Führer retreated further and further into his bunker, the secure catacomb beneath the Reich chancellery, from which Hitler could direct his last stand, the Götterdämmerung scenario made famous in movies such as Downfall.

After this compelling introduction, the narrative moves swiftly to the impending defeat of April 1945, and the shocking physical deterioration of the Führer’s final days, especially the drugs administered to him by a sinister cabal of Nazi doctors, to the point at which he became, in Trevor-Roper’s words, “a physical wreck”. Inside this murky hell-hole, there was, however, a figure of innocence, an Aryan maiden who would sacrifice herself for her hero.

At the moment when the young historian first investigated the bizarre and fascinating psychodrama of life in Hitler’s bunker, Eva Braun, who would marry her lover in the last days of April, was still an unknown. His portrait of Hitler’s devoted companion is one of the many mini-scoops scattered through these pages:

Braun had none of the colourful qualities of the conventional tyrant’s mistress, writes Trevor-Roper. But then neither was Hitler a typical tyrant. Behind his impassioned rages, his enormous ambition, his gigantic self-confidence, there lay not the indulgent ease of a voluptuary, but the trivial tastes, the conventional domesticity, of the petty-bourgeois. One cannot forget the cream buns.

|

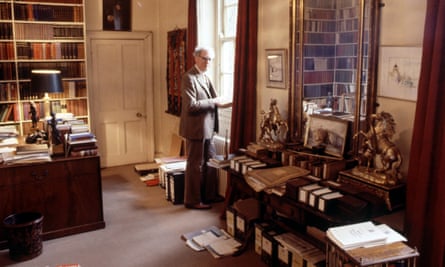

| Hugh Trevor-Roper at home in Oxford in 1980. Photograph: Graham Harrison/Rex Features |

Hitler’s 56th birthday fell on 20 April. Fifty feet underground, beneath the garden of the Reich chancellery, the Fuhrer struggled to direct an ever more desperate rearguard action as the allies, led by the Red Army, closed in on Nazi Berlin. On 22 April there was a three-hour conference of war at which, famously, Hitler’s rage exceeded all previous eruptions. He shrieked; he railed; he denounced; finally, in exhaustion, he declared that the end had come. By 27 April the heart of the city was cut off from the rest of Germany. Now the Russians were shelling it without mercy. As hope faded, Hitler’s court bade farewell. Incredibly, some were still reluctant to leave their master. However, at this juncture, there was a bitter distraction: the feuding at the top of the party between Bormann, Goering and Himmler added to the air of crisis surrounding life in the bunker.

After 27 April, Hitler’s days were numbered. Life in the bunker became progressively madder and more apocalyptic. Trevor-Roper extracts maximum theatricality from his narrative, describing the inferno of those last days. How, he asks, can the ordinary reader envisage the life that was led in those doomed, subterranean bunkers, amid perpetual shelling and bombing, often in total darkness, in which all count of the hours was lost; when meals took place at wayward hours, and the boundaries of night and day had been forgotten?

During the night of 27-28 April, with Red Army shelling cacophonously overhead, Hitler rehearsed with his court their plans for suicide and the various methods by which their corpses might be destroyed. Two days later, word came that Himmler had set himself up as a new Reichsführer, and was negotiating with the Swedes. In the delirium of treachery surrounding Hitler, this was the end.

And now the Wagnerian climax was complete, with a doomed protagonist to lend some weird poignancy to the drama. On Trevor-Roper’s account, Adolf Hitler presented a pathetic spectacle.

His look was abstracted, his eyes glazed over with a film of moisture. Some of those who saw him even suggested that he had been drugged… He walked in silence down the passage and shook hands with all the women in turn… The suicide of the Führer was about to take place. Thereupon an unexpected thing happened. The terrible sorcerer, the tyrant who had charged their days with melodramatic tension, would soon be gone, and for a brief twilight moment they could play. In the canteen of the chancellery, where the orderlies took their meals, there was a dance.

Soon after, a single shot was heard. After Eva Braun had taken poison, Hitler shot himself in the mouth. It was 3.30pm on 30 April 1945.

When it was first published, The Last Days of Hitler had a quasi-propaganda purpose: to prove, definitively, by brilliant detective work, that the Hitler was not only dead, but had killed himself.

This, triumphantly, Trevor-Roper achieved. His account has never seriously been challenged. More than that, he also contrived to interweave into his narrative a critique of the Nazi state and its origins that would help shape the prodigious historiography of the Hitler regime that blossomed like a pernicious weed throughout the second half of the 20th century.

So magisterial was Trevor-Roper, now Lord Dacre, in relation to Hitler studies that when in 1983 Britain’s Sunday Times, by then owned by Rupert Murdoch, acquired the rights to a set of notebooks purporting to be Hitler’s personal diaries, the now ageing but immensely distinguished historian was cynically deployed to authenticate the “Hitler Diaries”. In the media frenzy that surrounded the publication of “the scoop of the century”, Murdoch threw Trevor-Roper to the wolves, dismissing the elderly historian’s subsequent doubts with the memorably brutal: “Fuck Dacre. Publish.”

In the uproar that preceded the exposure of these documents as shameless forgeries, Trevor-Roper was first humiliated, then pilloried. (Initially, he had expressed doubts, then changed his mind under duress, and declared that they could be genuine, before finally agreeing that they were a fake.) His reputation never recovered.

He died in 2003, but his influence lingers. He wrote the first bestseller about Adolf Hitler, and has unquestionably inspired many subsequent generations of popular historians, journalists and novelists to follow the same mesmerising path into the Nazi state’s labyrinth of evil.

A signature sentence

“There, in scenes of Roman luxury, Goering feasted and hunted and entertained, and showed his distinguished guests round the architectural and artistic wonders of his house – a study like a medium-sized church, a domed library like the Vatican library, a desk 26ft long, of mahogany inlaid with bronze swastikas, furnished with two big golden baroque candelabra, and an inkstand all of onyx, and a long ruler of green ivory studded with jewels.”

Three to compare

Hugh Trevor-Roper: Hitler’s Table Talk (1951)

Robert Harris: Selling Hitler (1986)

Joachim Fest: Inside Hitler’s Bunker (2002)

The Last Days of Hitler is published by Pan (£9.99)

THE GUARDIAN002 The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion(2005)

009 Dispatches by Michael Herr (1977)

010 The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins

021 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S Kuhn (1962)

022 A Grief Observed by CS Lewis (1961)

No comments:

Post a Comment