The 100 best nonfiction books: No 15 – The Double Helix by James D Watson (1968)

An astonishingly personal and accessible account of how Cambridge scientists Watson and Francis Crick unlocked the secrets of DNA and changed the world

Robert McCrumb

Monday 9 May 2016

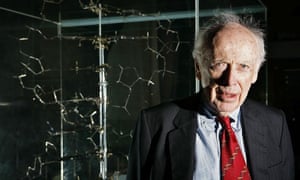

‘Uncompromisingly honest’: James Watson in 2007. Photograph: Edmond Terakopian/PA

But Watson had not abandoned his quest for glory. Covertly, he continued to work after hours at the Cavendish on the “helical” structure of DNA. By late 1952, Pauling had still made no new announcement. This was encouraging. “If Pauling had found a really exciting answer,” writes Watson, “the secret could not be kept for long. One of his graduate students must certainly know what his model looked like, and the rumour would have quickly reached us.” As it turned out, the news from California was far better than the Cambridge team could have expected. When, finally, Pauling did publish his latest theory, it contained a basic and fundamental flaw. Watson could not conceal his exhilaration: “Though the odds still appeared against us, Linus had not yet won his Nobel.”

In retrospect, though progress seemed agonisingly protracted and uncertain, Crick and Watson’s breakthrough occurred at warp speed, driven by “the American’s” obsessive ambition. Watson, indeed, never stopped testing new hypotheses for the structure of DNA against Crick’s wiser scepticism. Eventually, chance took a hand. It was a casual conversation Watson had with “an American crystallographer”, who had fortuitously been assigned to his lab, that provided the germ of the idea that would survive Crick’s scrutiny. On Watson’s account, it was during the late winter of 1953 that “Francis winged into the Eagle to tell everyone that we had found the secret of life”.

The “double helix”, commissioned by Watson, confronting Crick as a model in the lab, was at once supremely beautiful, wonderfully elegant and fundamentally simple. In Watson’s words: “Immediately [Crick] caught on to the complementary relation between the two chains and saw how an equivalence of adenine with thymine and guanine with cystosine was a logical consequence of the regular repeating shape of the sugar-phosphate backbone.”

Towards the end of March 1953, Crick and Watson began to write the 900-word article for Nature that would change biochemistry for ever, and add their names to the roll call of great scientists: “We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.” Rarely have two English sentences contained so much exhilarated understatement.

Watson’s research career, described in The Double Helix, a wide-eyed, whirlwind account of unheated university lodgings, handwritten correspondence, chance encounters in pubs or on the Cambridge train and unexpected phone calls, is a world away from the science of today. It is more than slightly personal and unequivocally “heroic”; it celebrates contingency and chance and the unscientific qualities of pride, secrecy, chauvinism and low cunning. It is raw, rash and unputdownable. In taking an impossibly complex subject and rendering an account for the ordinary reader, it has inspired a generation of accessible science writing as well as, perhaps, the popularising work of writers such as Malcolm Gladwell (Blink; Outliers) and Michael Lewis (The New New Thing).

A signature sentence

“Excitedly, I pilfered Bernal and Fankuchen’s paper from the Philosophical Library and brought it up to the lab so that Francis could inspect the TMV X-ray picture.”

Three to compare

Erwin Schrödinger: What Is Life? (1944)

Francis Crick: Of Molecules and Men (1966)

Brenda Maddox: Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA (2002)

The Double Helix is published by Phoenix House (£9.99).

001 The Sixth Extintion by Elizabeth Kolbert (2004)

002 The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion(2005)

002 The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion(2005)

003 No Logo by Noami Klein (1999)

004 Birthday Letters by Ted Hughes (1998)

005 Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama (1995)

006 A brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking (1988)

007 The Right Stuff by Tom Wolfe (1979)

008 Orientalism by Edward Said (1978)009 Dispatches by Michael Herr (1977)

010 The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins

011 North by Seamus Heaney (1975)

012 Awekenings by Oliver Sacks (1973)

013 The Female Eunuch by Germaine Greer (1970)

014 Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom by Nick Cohn (1969)

015 The Double Helix by James D Watson (1968)

016 Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag (1966)017 Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965)

018 The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan (1963)

020 Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962)

021 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S Kuhn (1962)

022 A Grief Observed by CS Lewis (1961)

021 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S Kuhn (1962)

022 A Grief Observed by CS Lewis (1961)

026 Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin (1955)

028 The Hedgehog and the Fox by Isaiah Berlin (1953)

029 Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett (1952 / 53)

036 Black Boy by Richard Wright (1945)

No comments:

Post a Comment