|

| Hiroshima |

Story of cities #24: how Hiroshima rose from the ashes of nuclear destruction

In August 1945, a 16-kilotonne atomic bomb killed 140,000 people and reduced a thriving city to rubble. Hiroshima has been reborn as a place of peace and prosperity, but will memories of those dark days die with the last survivors?

Justin McCurry in HiroshimaMonday 18 April 2016

The people of Hiroshima have developed a verbal shorthand for describing their city’s layout. A particular street is “about 1.5 kilometres away”; a building “500 metres north”. No further explanation is required. The unspoken reference point is the hypocentre of the world’s first nuclear attack.

At first glance, visitors arriving by bullet train to Hiroshima’s main railway station might have little inkling of the city’s singularly tragic past. On a warm spring evening, groups of European tourists pause outside restaurants offering special deals on oysters – a local delicacy – and board pleasure boats to Miyajima, an island famous for its wild deer and “floating” Shinto shrine. But reminders of history’s antithesis to these quotidian pleasures are never far away.

South-west of the station, visitors to the city’s Peace Memorial Museum fall silent in front of steps retrieved from the ruins of Sumitomo Bank, the “shadow” of a human etched into the stone. Display cases show the shredded remains of a junior high-school uniform, the irradiated contents of a lunchbox and the frame of a tricycle – the small boy riding it was incinerated by the blast.

These harrowing exhibits are among the few physical reminders of the devastation that greeted survivors after the US B-29 bomber Enola Gay released Little Boy, a 16-kilotonne atomic bomb, over Hiroshima at 8.15am on 6 August 1945.

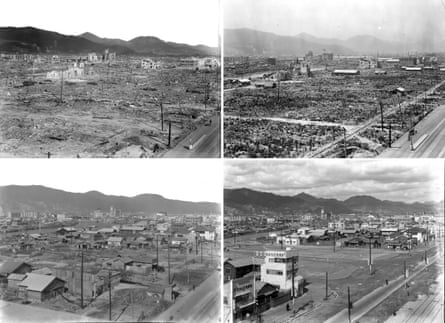

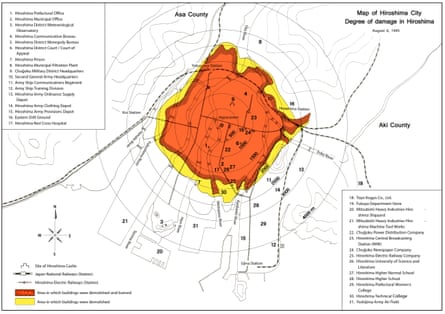

Less than a minute later, the bomb exploded 600 metres above Shima Hospital, creating a wave of heat that momentarily reached 3,000-4,000 degrees centigrade on the ground. Winds of up to 440 metres per second roared through the entire city. Within half an hour, almost every building within a two-kilometre radius of the hypocentre was in flames. About 90% of the city’s 76,000 buildings were partially or totally incinerated, or reduced to rubble. Of the 33m square metres of land considered usable before the attack, 40% was reduced to ashes.

The bombed city was barely recognisable. What a day earlier had been a sprawling military city and transportation hub, wedged between mountain ranges to the north and the Seto inland sea to the south, was now a nuclear wasteland. Wooden homes had been burnt to the ground by firestorms; the city’s rivers were filled with the corpses of people desperately seeking water before they died. With the exception of a handful of concrete buildings, Hiroshima had ceased to exist.

A day after the attack, Keiko Ogura, then an eight-year-old schoolgirl, could barely believe her eyes as she looked down on her hometown from a hill. “The entire city had been burned to the ground,” says Ogura, one of many hibakusha – the Japanese name given to people exposed to radiation – who pass on their experience to visitors. “None of us could comprehend what had happened … we kept asking ourselves how an entire city could have been destroyed by a single bomb.”

Ogura, whose home narrowly escaped the firestorms, recalls seeing people shorn of their skin, almost indistinguishable from what remained of their clothes. While her father cremated hundreds of corpses in the open, Ogura gave water to the severely injured, only to watch them die in front of her.

“That was the beginning of a trauma that would stay with me for many years,” she says. “Talking about it now is a way of healing the psychological scars. It feels like I am doing something useful on behalf of the people who died.”

The blast instantly killed 80,000 of the Hiroshima’s 420,000 residents; by the end of the year, the death toll would rise to 141,000 as survivors succumbed to injuries or illnesses connected to their exposure to radiation.

Yet even as they struggled to comprehend the horror visited on their homes, businesses, public buildings and fellow citizens, evidence emerged of remarkable acts of courage and resourcefulness. Incredible though it may seem, looking at the handful of black-and-white photos taken in the immediate aftermath of the attack, Hiroshima’s resurrection began just hours after it was effectively wiped from the map.

The lights came back on in the Ujina area on 7 August, and around Hiroshima railway station a day later. Power was restored to 30% of homes that had escaped fire damage, and to all households by the end of November 1945, according to records kept by the Hiroshima Peace Institute.

Water pumps were repaired and started working again four days after the bombing, although damaged pipes created vast puddles among the ashes of wooden homes. The central telephone exchange bureau was destroyed and all of its employees killed, yet essential equipment was retrieved and repaired, and by the middle of August 14 experimental lines were back in operation.

Eighteen workers and a dozen finance bureau employees at the Hiroshima branch of the Bank of Japan, one of the city’s few concrete buildings, died instantly, yet the bank reopened two days later, offering floor space to 11 other banks whose premises had been destroyed. Tellers worked under open skies in clear weather, and beneath umbrellas when it rained.

A limited streetcar service resumed on 9 August, the same day Nagasaki was destroyed by a plutonium bomb, killing more than 70,000 people. With the need to move people and supplies into the city growing more urgent by the hour, the Ujina railway line started moving again on 7 August; a day later, trains on the Sanyo Line started running the short distance between Hiroshima and Yokogawa stations.

Higashi Police Station, despite being inside the two-kilometre radius, was commandeered by the prefectural government and turned into the nerve centre for search and rescue and relief operations.

Historians say the quick resumption of services was a civic effort, helped by the arrival of large numbers of volunteers. “I do not think the restoration of basic services was simply due to coercion from the authorities,” says Yuki Tanaka, a historian and former professor at Hiroshima City University. “Hiroshima received a lot of help from people in neighbouring towns and cities such as Fuchu, Kure, and even Yamaguchi. In this sense, the response was similar to that seen after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, when many people throughout Japan went to the devastated areas and helped the victims.”

Weeks after Hiroshima felt the unforgiving force of nuclear fission, nature compounded the city’s misery. Makurazaki, an unusually powerful typhoon, swept through the city on 17 September, flooding large areas and ruining many of the temporary hospitals set up on the outskirts. “The only good thing that came of it was that it washed a lot of the residual radiation into the sea,” says Tanaka. “After the typhoon, radiation levels fell considerably.”

It was inevitable, given the scale of destruction, that early attempts to re-establish a semblance of civic life on the scorched earth of ground zero were marked by chaos and confusion. The mayor, Senkichi Awaya, was among the dead, leaving the city without a leader; thousands of public servants, teachers and health professionals were also among the victims. On 6 August the municipal government office employed about 1,000 people; the following day just 80 reported for duty.

“They alone had to deal with emergency medical treatment, establish a food supply and retrieve and cremate corpses,” says Tanaka. “They were incredibly difficult times.” Attempts to care for the dying and seriously wounded verged on the futile: 14 of Hiroshima’s 16 major hospitals no longer existed; 270 of 298 hospital doctors were dead, along with 1,654 of 1,780 registered nurses. Demand for housing turned the area near the hypocentre into a shantytown of 10,000 homes that were little more than wooden shacks, with sanitary facilities shared among several households.

US soldiers arrived in Hiroshima in 1946, but direct control of the city was given to troops from the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, headquartered in the nearby port city of Kure. “There are no records of foreign troops actually helping with reconstruction, but they were vital to the flow of emergency supplies,” says Ariyuki Fukushima of the Peace Memorial Museum’s curatorial division. “And the [US-led] occupation forces facilitated the recovery in a broad sense, since they gave final approval to public works projects.”

Although it was initially one of five Japanese cities under consideration by US president Harry Truman and his advisers, there are compelling reasons why the Americans targeted Hiroshima. Having begun as a castle town at the end of the 1500s under the rule of the feudal warlord Mori Terumoto, by the end of the 19th century it served as a regional garrison for the Imperial Japanese Army; as a major manufacturing centre, it helped fuel the Japanese empire’s military efforts in the Asia-Pacific.

Slow transformation

It was only after the strained tones of Emperor Hirohito confirmed Japan’s surrender in a radio broadcast on 15 August 1945 that reconstruction replaced war as the nation’s clarion call. With factories commandeered for the war effort now back in private ownership, local authorities launched a five-year recovery plan to dramatically raise production. Ironically, it was another conflict, on the Korean peninsula, that gave the local economy a fillip, as demand soared for canned food, cars and other goods. A second boom came in 1952, when the departing Allied occupation authorities lifted the ban on Japanese shipbuilding.

The idea of transforming a large area of Hiroshima into a memorial to the A-bomb dead gained traction in 1946, when the local Chugoku Shimbun newspaper ran a competition soliciting readers’ visions for the city. First prize was awarded to Sankichi Tōge, a poet, peace activist and A-bomb survivor – although some have speculated that his brother contributed many of the ideas in his essay. Tōge, who died in 1953 aged 36, envisioned a peace plaza memorial, a library, museum and a place where visitors from around the world could come together to dedicate themselves to peace. About 40% of the city should be covered in greenery, he said.

The city government was sympathetic to Tōge’s utopian vision, but lacked the money to act. Tax revenue had plummeted by 80% from pre-attack levels and parts of the city, including a military base near Hiroshima castle, still belonged to the state. The turning point came in 1949, when national politicians, recognising Hiroshima’s special status, passed the Peace Memorial City Construction Law, Article 1 of which states: “Hiroshima is to be a peace memorial city symbolising the human idea of the sincere pursuit of genuine and lasting peace.”

Sources of funding once closed to city planners were opened, and the central government agreed to turn over state and military-owned land free of charge. If the reconstruction law resolved questions of land ownership and removed the financial obstacles that had slowed Hiroshima’s recovery, Japan’s postwar economic miracle heralded an age of breakneck construction. In 1958, the city’s population returned to its pre-war level of 410,000. “That was a kind of springboard for recovery,” says Fukushima.

But work on the peace memorial city project exposed social divisions that predated the bombing. The demolition of thousands of wooden shacks in the area earmarked for development forced residents – among them forced Korean labourers and members of the burakumin underclass – to relocate to the banks of the Ota River. Within months, more than 3,000 people were living on the riverbank with no access to running water or electricity. Fires regularly swept through the ramshackle huts, which remained until the local government built high-rise flats in 1970.

As Tōge and others had envisaged, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park occupies prime real estate south-west of the main railway station, with the 100m-wide peace boulevard, which traverses the city centre, running along the park’s southern boundary. Designed by the Japanese architect Kenzō Tange and completed in the late 1950s, the three-acre site now houses a museum, a conference hall and a cenotaph honouring the victims of the bombing and every survivor who has since died. As of last August that number had reached 297,684.

City planners, though, faced a dilemma: how to incorporate Hiroshima’s tragic history within its postwar reincarnation. Kenji Shiga, director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, said some officials favoured removing every last physical remnant of the tragedy, while others insisted on preserving evidence of the atomic bomb’s destructive power.

The outcome of that debate is visible in the remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, better known these days as the A-bomb Dome. “Some people thought it should be torn down and that Hiroshima should be a completely new city,” says Shiga. “The hibakusha in particular didn’t want to see reminders of what had happened. That was one example of how difficult it was – and still is – to strike a balance between recognising the facts of history and building a modern city.”

The A-bomb Dome’s future was secured in the mid-1960s, when officials agreed to preserve it; in 1996 it became a Unesco world heritage site. Today, it stands as one of the few relics of a Hiroshima that not many of its 1.2 million residents are now old enough to remember. Younger citizens fret over the fortunes of the local baseball and football teams, the Hiroshima Toyo Carp and Sanfrecce Hiroshima. Their hometown is now considered so typical of Japan’s cities that firms often market new products here before deciding whether to sell them nationwide.

The A-bomb Dome, the Peace Park and preserved buildings such as the former Hiroshima branch of the Bank of Japan are the only architectural reminders of the attack. Elsewhere, Hiroshima looks much like any other Japanese city: featureless office and apartment blocks, pockets of neon-lit nightlife, and the ubiquitous convenience stores and chain coffee shops. Looking down from a pedestrian bridge at trams and taxis negotiating their way through streets lined with office buildings and chain restaurants, the overriding impression is of a prosperous, friendly city that has come to terms with its past. But with adult survivors now in their 80s and 90s, fears are growing that memories of the city’s dark history will die out along with the last of those who bore witness to the violent dawn of the atomic age.

The 183,519 registered hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are entitled to a monthly allowance and free medical care. Many are succumbing to illnesses that are associated with old age but which could be connected to their exposure to radiation, as documented by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, a Japan and US-funded body set up in 1975 to investigate the health effects among Japan’s nuclear survivors.

“The cancer rate among elderly A-bomb survivors is high,” according to Tanaka. “Many A-bomb survivors have been fighting various cancers and other illnesses typically caused by radiation, such as heart problems, cataracts and leukaemia. There are very few survivors who have not experienced health problems as they’ve grown older.”

The city they leave behind will be lasting testament to the horror they experienced, and to their determination to rebuild against the odds, according to Hiroshima’s mayor, Kazumi Matsui. “Humans destroyed Hiroshima, but humans also rebuilt it,” he says. “This is a holy site … somewhere people can come to compare the horrors of the past with the city Hiroshima has become today.”

No comments:

Post a Comment