I Tried to Be a Communist

“I asked for a definition of what was expected from the writers—books or political activity. Both, was the answer.”

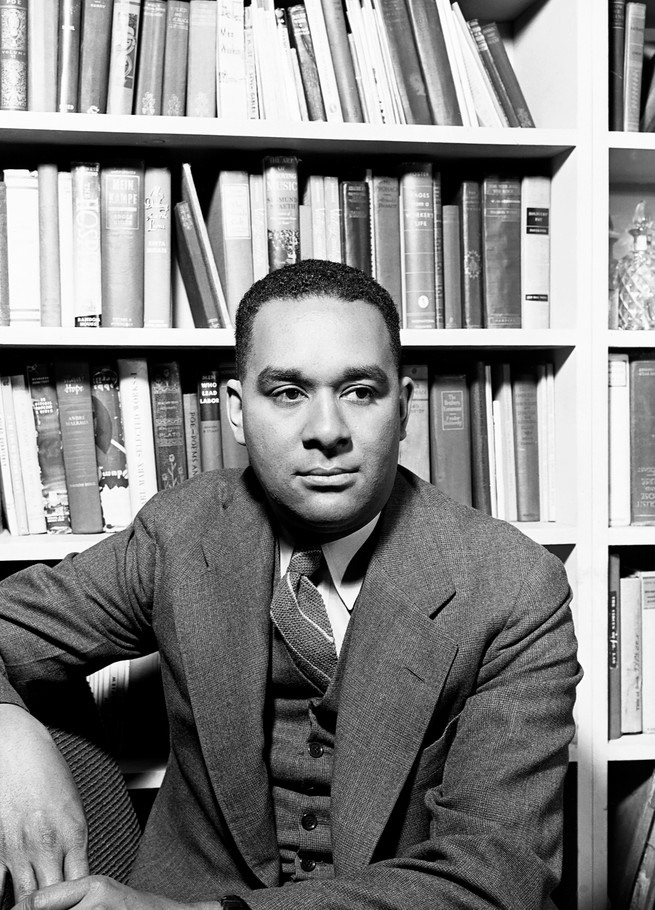

Editor’s Note: The Atlantic published “I Tried to Be a Communist” in two parts, in the August and September 1944 issues. In the essay, the author Richard Wright, who had published the novel Native Son in 1940, recounted what first drew him to the Communist Party in the 1930s, and what ultimately drove him away from it.

In the June 2021 issue of the magazine, Imani Perry considers The Man Who Lived Underground, a previously unpublished novel written by Wright in the early 1940s. Some of Wright’s contemporaries were critical of what they saw as the incursion of politics into his art; Ralph Ellison, Perry notes, thought that Wright “wrote fiction that was too ideological and not sensitive enough to nuance.” But, Perry argues, “Wright deserves to be looked at with fresh eyes.” “I Tried to Be a Communist,” which shows Wright wrestling with the uneasy relationship between Communism and his writing, is a good place to start.

1

One thursday night I received an invitation from a group of white boys I had known when I was working in the post office to meet in one of Chicago’s South Side hotels and argue the state of the world. About ten of us gathered, and ate salami sandwiches, drank beer, and talked. I was amazed to discover that many of them had joined the Communist Party. I challenged them by reciting the antics of the Negro Communists I had seen in the parks, and I was told that those antics were “tactics” and were all right. I was dubious.

Then one Thursday night Sol, a Jewish chap, startled us by announcing that he had had a short story accepted by a little magazine called the Anvil, edited by Jack Conroy, and that he had joined a revolutionary artist organization, the John Reed Club. Sol repeatedly begged me to attend the meetings of the club.

“You’d like them,” Sol said.

“I don’t want to be organized,” I said.

“They can help you to write,” he said.

“Nobody can tell me how or what to write,” I said.

“Come and see,” he urged. “What have you to lose?”

I felt that Communists could not possibly have a sincere interest in Negroes. I was cynical and I would rather have heard a white man say that he hated Negroes, which I could have readily believed, than to have heard him say that he respected Negroes, which would have made me doubt him.

One Saturday night, bored with reading, I decided to appear at the John Reed Club in the capacity of an amused spectator. I rode to the Loop and found the number. A dark stairway led upwards; it did not look welcoming. What on earth of importance could happen in so dingy a place? Through the windows above me I saw vague murals along the walls. I mounted the stairs to a door that was lettered: the chicago john reed club.

I opened it and stepped into the strangest room I had ever seen. Paper and cigarette butts lay on the floor. A few benches ran along the walls, above which were vivid colors depicting colossal figures of workers carrying streaming banners. The mouths of the workers gaped in wild cries; their legs were sprawled over cities.

“Hello.”

I turned and saw a white man smiling at me.

“A friend of mine, who’s a member of this club, asked me to visit here. His name is Sol ——,” I told him.

“You’re welcome here,” the white man said. “We’re not having an affair tonight. We’re holding an editorial meeting. Do you paint?” He was slightly gray and he had a mustache.

“No,” I said. “I try to write.”

“Then sit on the editorial meeting of our magazine, Left Front,” he suggested.

“I know nothing of editing,” I said.

“You can learn,” he said.

I stared at him, doubting.

“I don’t want to be in the way here,” I said.

“My name’s Grimm,” he said.

I told him my name and we shook hands. He went to a closet and returned with an armful of magazines.

“Here are some back issues of the Masses,” he said. “Have you ever read it?”

“No,” I said.

“Some of the best writers in America publish in it,” he explained. He also gave me copies of a magazine called International Literature. “There’s stuff here from Gide, Gorky —“

I assured him that I would read them. He took me to an office and introduced me to a Jewish boy who was to become one of the nation’s leading painters, to a chap who was to become one of the eminent composers of his day, to a writer who was to create some of the best novels of his generation, to a young Jewish boy who was destined to film the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. I was meeting men and women whom I should know for decades to come, who were to form the first sustained relationships in my life.

I sat in a corner and listened while they discussed their magazine, Left Front. Were they treating me courteously because I was a Negro? I must let cold reason guide me with these people, I told myself. I was asked to contribute something to the magazine, and I said vaguely that I would consider it. After the meeting I met an Irish girl who worked for an advertising agency, a girl who did social work, a schoolteacher, and the wife of a prominent university professor. I had once worked as a servant for people like these and I was skeptical. I tried to fathom their motives, but I could detect no condescension in them.

2

Iwent home full of reflection, probing the sincerity of the strange white people I had met, wondering how they really regarded Negroes. I lay on my bed and read the magazines and was amazed to find that there did exist in this world an organized search for the truth of the lives of the oppressed and the isolated. When I had begged bread from the officials, I had wondered dimly if the outcasts could become united in action, thought, and feeling. Now I knew. It was being done in one sixth of the earth already. The revolutionary words leaped from the printed page and struck me with tremendous force.

It was not the economics of Communism, nor the great power of trade unions, nor the excitement of underground politics that claimed me; my attention was caught by the similarity of the experiences of workers in other lands, by the possibility of uniting scattered but kindred peoples into a whole. It seemed to me that here at last, in the realm of revolutionary expression, Negro experience could find a home, a functioning value and role. Out of the magazines I read came a passionate call for the experiences of the disinherited, and there were none of the lame lispings of the missionary in it. It did not say: “Be like us and we like you, maybe.” It said: “If you possess enough courage to speak out what you are, you will find that you are not alone.” It urged life to believe in life.

I read into the night; then, toward dawn, I swung from bed and inserted paper into the typewriter. Feeling for the first time that I could speak to listening ears, I wrote a wild, crude poem in free verse, coining images of black hands playing, working, holding bayonets, stiffening finally in death. I felt that in a clumsy way it linked white life with black, merged two streams of common experience.

I heard someone poking about the kitchen.

“Richard, are you ill?” my mother called.

“No. I’m reading.”

My mother opened the door and stared curiously at the pile of magazines that lay upon my pillow.

“You’re not throwing away money buying those magazines, are you?” she asked.

“No. They were given to me.”

She hobbled to the bed on her crippled legs and picked up a copy of the Masses that carried a lurid May Day cartoon. She adjusted her glasses and peered at it for a long time.

“My God in heaven,” she breathed in horror.

“What’s the matter, Mama?”

“What is this?” she asked, extending the magazine to me, pointing to the cover. “What’s wrong with that man?”

With my mother standing at my side, lending me her eyes, I stared at a cartoon drawn by a Communist artist; it was the figure of a worker clad in ragged overalls and holding aloft a red banner. The man’s eyes bulged; his mouth gaped as wide as his face; his teeth showed; the muscles of his neck were like ropes. Following the man was a horde of nondescript men, women, and children, waving clubs, stones, and pitchforks.

“What are those people going to do?” my mother asked.

“I don’t know,” I hedged.

“Are these Communist magazines?”

“Yes.”

“And do they want people to act like this?”

“Well —“ I hesitated.

My mother’s face showed disgust and moral loathing. She was a gentle woman. Her ideal was Christ upon the cross. How could I tell her that the Communist Party wanted her to march in the streets, chanting, singing?

“What do Communists think people are?” she asked.

“They don’t quite mean what you see there,” I said, fumbling with my words.

“Then what do they mean?”

“This is symbolic,” I said.

“Then why don’t they speak out what they mean?”

“Maybe they don’t know how.”

“Then why do they print this stuff?”

“They don’t quite know how to appeal to people yet,” I admitted, wondering whom I could convince of this if I could not convince my mother.

“That picture’s enough to drive a body crazy,” she said, dropping the magazine, turning to leave, then pausing at the door. “You’re not getting mixed up with those people?”

“I’m just reading, Mama,” I dodged.

My mother left and I brooded upon the fact that I had not been able to meet her simple challenge. I looked again at the cover of the Masses and I knew that the wild cartoon did not reflect the passions of the common people. I reread the magazine and was convinced that much of the expression embodied what the artists thought would appeal to others, what they thought would gain recruits. They had a program, an ideal, but they had not yet found a language.

Here, then, was something that I could do, reveal, say. The Communists, I felt, had oversimplified the experience of those whom they sought to lead. In their efforts to recruit masses, they had missed the meaning of the lives of the masses, had conceived of people in too abstract a manner. I would try to put some of that meaning back. I would tell Communists how common people felt, and I would tell common people of the self-sacrifice of Communists who strove for unity among them.

The editor of Left Front accepted two of my crude poems for publication, sent two of them to Jack Conroy’s Anvil, and sent another to the New Masses, the successor of the Masses. Doubts still lingered in my mind.

“Don’t send them if you think they aren’t good enough,” I said to him.

“They’re good enough,” he said.

“Are you doing this to get me to join up?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “Your poems are crude, but good for us. You see, we’re all new in this. We write articles about Negroes, but we never see any Negroes. We need your stuff.”

I sat through several meetings of the club and was impressed by the scope and seriousness of its activities. The club was demanding that the government create jobs for unemployed artists; it planned and organized art exhibits; it raised funds for the publication of Left Front; and it sent scores of speakers to trade-union meetings. The members were fervent, democratic, restless, eager, self-sacrificing. I was convinced, and my response was to set myself the task of making Negroes know what Communists were. I got the notion of writing a series of biographical sketches of Negro Communists. I told no one of my intentions, and I did not know how fantastically naïve my ambition was.

3

Ihad attended but a few meetings before I realized that a bitter factional fight was in progress between two groups of members of the club. Sharp arguments rose at every meeting. I noticed that a small group of painters actually led the club and dominated its policies. The group of writers that centered in Left Front resented the leadership of the painters. Being primarily interested in Left Front, I sided in simple loyalty with the writers.

Then came a strange development. The Left Front group declared that the incumbent leadership did not reflect the wishes of the club. A special meeting was called and a motion was made to reelect an executive secretary. When nominations were made for the office, my name was included. I declined the nomination, telling the members that I was too ignorant of their aims to be seriously considered. The debate lasted all night. A vote was taken in the early hours of morning by a show of hands, and I was elected.

Later I learned what had happened: the writers of the club had decided to use me to oust the painters, who were party members, from the leadership of the club. Without my knowledge and consent, they confronted the members of the party with a Negro, knowing that it would be difficult for Communists to refuse to vote for a man representing the largest single racial minority in the nation, inasmuch as Negro equality was one of the main tenets of Communism.

As the club’s leader, I soon learned the nature of the fight. The Communists had secretly organized a “fraction” in the club; that is, a small portion of the club’s members were secret members of the Communist Party. They would meet outside of the club and decide what policies the club should follow; in club meetings the sheer strength of their arguments usually persuaded non-party members to vote with them. The crux of the fight was that the nonparty members resented the excessive demands made upon the club by the local party authorities through the fraction.

The demands of the local party authorities for money, speakers, and poster painters were so great that the publication of Left Front was in danger. Many young writers had joined the club because of their hope of publishing in Left Front, and when the Communist Party sent word through the fraction that the magazine should be dissolved, the writers rejected the decision, an act which was interpreted as hostility toward party authority.

I pleaded with the party members for a more liberal program for the club. Feelings waxed violent and bitter. Then the showdown came. I was informed that if I wanted to continue as secretary of the club I should have to join the Communist Party. I stated that I favored a policy that allowed for the development of writers and artists. My policy was accepted. I signed the membership card.

One night a Jewish chap appeared at one of our meetings and introduced himself as Comrade Young of Detroit. He told us that he was a member of the Communist Party, a member of the Detroit John Reed Club, that he planned to make his home in Chicago. He was a short, friendly, black-haired, well-read fellow with hanging lips and bulging eyes. Shy of forces to execute the demands of the Communist Party, we welcomed him. But I could not make out Young’s personality; whenever I asked him a simple question, he looked off and stammered a confused answer. I decided to send his references to the Communist Party for checking and forthwith named him for membership in the club. He’s O.K., I thought. Just a queer artist.

After the meeting Comrade Young confronted me with a problem. He had no money, he said, and asked if he could sleep temporarily on the club’s premises. Believing him loyal, I gave him permission. Straightway Young became one of the most ardent members of the organization, admired by all. His paintings — which I did not understand —impressed our best artists. No report about Young had come from the Communist Party, but since Young seemed a conscientious worker, I did not think the omission serious in any case.

At a meeting one night Young asked that his name be placed upon the agenda; when his time came to speak, he rose and launched into one of the most violent and bitter political attacks in the club’s history upon Swann, one of the best young artists. We were aghast. Young accused Swann of being a traitor to the worker, an opportunist, a collaborator with the police, and an adherent of Trotsky. Naturally most of the club’s members assumed that Young, a member of the party, was voicing the ideas of the party. Surprised and baffled, I moved that Young’s statement be referred to the executive committee for decision. Swann rightfully protested; he declared that he had been attacked in public and would answer in public.

It was voted that Swann should have the floor. He refuted Young’s wild charges, but the majority of the club’s members were bewildered, did not know whether to believe him or not. We all liked Swann, did not believe him guilty of any misconduct; but we did not want to offend the party. A verbal battle ensued. Finally the members who had been silent in deference to the party rose and demanded of me that the foolish charges against Swann be withdrawn. Again I moved that the matter be referred to the executive committee, and again my proposal was voted down. The membership had now begun to distrust the party’s motives. They were afraid to let an executive committee, the majority of whom were party members, pass upon the charges made by party member Young.

A delegation of members asked me later if I had anything to do with Young’s charges. I was so hurt and humiliated that I disavowed all relations with Young. Determined to end the farce, I cornered Young and demanded to know who had given him authority to castigate Swann.

“I’ve been asked to rid the club of traitors.”

“But Swann isn’t a traitor,” I said.

“We must have a purge,” he said, his eyes bulging, his face quivering with passion.

I admitted his great revolutionary fervor, but I felt that his zeal was a trifle excessive. The situation became worse. A delegation of members informed me that if the charges against Swann were not withdrawn, they would resign in a body. I was frantic. I wrote to the Communist Party to ask why orders had been issued to punish Swann, and a reply came back that no such orders had been issued. Then what was Young up to? Who was prompting him? I finally begged the club to let me place the matter before the leaders of the Communist Party. After a violent debate, my proposal was accepted.

One night ten of us met in an office of a leader of the party to hear Young restate his charges against Swann. The party leader, aloof and amused, gave Young the signal to begin. Young unrolled a sheaf of papers and declaimed a list of political charges that excelled in viciousness his previous charges. I stared at Young, feeling that he was making a dreadful mistake, but fearing him because he had, by his own account, the sanction of high political authority.

When Young finished, the party leader asked, “Will you allow me to read these charges?”

“Of course,” said Young, surrendering a copy of his indictment. “You may keep that copy. I have ten carbons.”

“Why did you make so many carbons?” the leader asked.

“I didn’t want anyone to steal them,” Young said.

“If this man’s charges against me are taken seriously,” Swann said, “I’ll resign and publicly denounce the club.”

“You see!” Young yelled. “He’s with the police!”

I was sick. The meeting ended with a promise from the party leader to read the charges carefully and render a verdict as to whether Swann should be placed on trial or not. I was convinced that something was wrong, but I could not figure it out. One afternoon I went to the club to have a long talk with Young; but when I arrived, he was not there. Nor was he there the next day. For a week I sought Young in vain. Meanwhile the club’s members asked his whereabouts and they would not believe me when I told them I did not know. Was he ill? Had he been picked up by the police?

One afternoon Comrade Grimm and I sneaked into the club’s headquarters and opened Young’s luggage. What we saw amazed and puzzled us. First of all, there was a scroll of paper twenty yards long — one page pasted to another — which had drawings depicting the history of the human race from a Marxist point of view. The first page read: A Pictorial Record of Man’s Economic Progress.

“This is terribly ambitious,” I said.

“He’s very studious,” Grimm said.

There were long dissertations written in longhand: some were political and others dealt with the history of art. Finally we found a letter with a Detroit return address and I promptly wrote asking news of our esteemed member. A few days later a letter came which said in part: —

dear sir:

In reply to your letter, we beg to inform you that Mr. Young, who was a patient in our institution and who escaped from our custody a few months ago, had been apprehended and returned to this institution for mental treatment.

I was thunderstruck. Was this true? Undoubtedly it was. Then what kind of club did we run that a lunatic could step into it and help run it? Were we all so mad that we could not detect a madman when we saw one?

I made a motion that all charges against Swann be dropped, which was done. I offered Swann an apology, but as the leader of the Chicago John Reed Club I was a sobered and chastened Communist.

4

The communist party fraction in the John Reed Club instructed me to ask my party cell—or “unit,” as it was called—to assign me to full duty in the work of the club. I was instructed to give my unit a report of my activities, writing, organizing, speaking. I agreed and wrote the report.

A unit, membership in which is obligatory for all Communists, is the party’s basic form of organization. Unit meetings are held on certain nights which are kept secret for fear of police raids. Nothing treasonable occurs at these meetings; but once one is a Communist, one does not have to be guilty of wrongdoing to attract the attention of the police.

I went to my first unit meeting—which was held in the Black Belt of the South Side—and introduced myself to the Negro organizer.

“Welcome, comrade,” he said, grinning. “We’re glad to have a writer with us.”

“I’m not much of a writer,” I said.

The meeting started. About twenty Negroes were gathered. The time came for me to make my report and I took out my notes and told them how I had come to join the party, what few stray items I had published, what my duties were in the John Reed Club. I finished and waited for comment. There was silence. I looked about. Most of the comrades sat with bowed heads. Then I was surprised to catch a twitching smile on the lips of a Negro woman. Minutes passed. The Negro woman lifted her head and looked at the organizer. The organizer smothered a smile. Then the woman broke into unrestrained laughter, bending forward and burying her face in her hands. I stared. Had I said something funny?

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

The giggling became general. The unit organizer, who had been dallying with his pencil, looked up.

“It’s all right, comrade,” he said. “We’re glad to have a writer in the party.”

There was more smothered laughter. What kind of people were these? I had made a serious report and now I heard giggles.

“I did the best I could,” I said uneasily. “I realize that writing is not basic or important. But, given time, I think I can make a contribution.”

“We know you can, comrade,” the black organizer said.

His tone was more patronizing than that of a Southern white man. I grew angry. I thought I knew these people, but evidently I did not. I wanted to take issue with their attitude, but caution urged me to talk it over with others first.

During the following days I learned through discreet questioning that I had seemed a fantastic element to the black Communists. I was shocked to hear that I, who had been only to grammar school, had been classified as an intellectual. What was an intellectual? I had never heard the word used in the sense in which it was applied to me. I had thought that they might refuse me on the ground that I was not politically advanced; I had thought they might say I would have to be investigated. But they had simply laughed.

I learned, to my dismay, that the black Communists in my unit had commented upon my shined shoes, my clean shirt, and the tie I had worn. Above all, my manner of speech had seemed an alien thing to them.

“He talks like a book,” one of the Negro comrades had said. And that was enough to condemn me forever as bourgeois.

5

In my party work I met a Negro Communist, Ross, who was under indictment for “inciting to riot.” Ross typified the effective street agitator. Southern-born, he had migrated north and his life reflected the crude hopes and frustrations of the peasant in the city. Distrustful but aggressive, he was a bundle of the weaknesses and virtues of a man struggling blindly between two societies, of a man living on the margin of a culture. I felt that if I could get his story I could make known some of the difficulties inherent in the adjustment of a folk people to an urban environment; I should make his life more intelligible to others than it was to himself.

I approached Ross and explained my plan. He was agreeable. He invited me to his home, introduced me to his Jewish wife, his young son, his friends. I talked to Ross for hours, explaining what I was about, cautioning him not to relate anything that he did not want to divulge.

“I’m after the things that made you a Communist,” I said.

Word spread in the Communist Party that I was taking notes on the life of Ross, and strange things began to happen. A quiet black Communist came to my home one night and called me out to the street to speak to me in private. He made a prediction about my future that frightened me.

“Intellectuals don’t fit well into the party, Wright,” he said solemnly.

“But I’m not an intellectual,” I protested. “I sweep the streets for a living.” I had just been assigned by the relief system to sweep the streets for thirteen dollars a week.

“That doesn’t make any difference,” he said. “We’ve kept records of the trouble we’ve had with intellectuals in the past. It’s estimated that only 13 per cent of them remain in the party.”

“Why do they leave, since you insist upon calling me an intellectual?” I asked.

“Most of them drop out of their own accord.”

“Well, I’m not dropping out,” I said.

“Some are expelled,” he hinted gravely.

“For what?”

“General opposition to the party’s policies,” he said.

“But I’m not opposing anything in the party.”

“You’ll have to prove your revolutionary loyalty.”

“How?”

“The party has a way of testing people.”

“Well, talk. What is this?”

“How do you react to police?”

“I don’t react to them,” I said. “I’ve never been bothered by them.”

“Do you know Evans?” he asked, referring to a local militant Negro Communist.

“Yes. I’ve seen him; I’ve met him.”

“Did you notice that he was injured?”

“Yes. His head was bandaged.”

“He got that wound from the police in a demonstration,” he explained. “That’s proof of revolutionary loyalty.”

“Do you mean that I must get whacked over the head by cops to prove that I’m sincere?” I asked.

“I’m not suggesting anything,” he said. “I’m explaining.”

“Look. Suppose a cop whacks me over the head and I suffer a brain concussion. Suppose I’m nuts after that. Can I write then? What shall I have proved?”

He shook his head. “The Soviet Union has had to shoot a lot of intellectuals,” he said.

“Good God!” I exclaimed. “Do you know what you’re saying? You’re not in Russia. You’re standing on a sidewalk in Chicago. You talk like a man lost in a fantasy.”

“You’ve heard of Trotsky, haven’t you?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you know what happened to him?”

“He was banished from the Soviet Union,” I said.

“Do you know why?”

“Well,” I stammered, trying not to reveal my ignorance of politics, for I had not followed the details of Trotsky’s fight against the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, “it seems that after a decision had been made, he broke that decision by organizing against the party.”

“It was for counter-revolutionary activity,” he snapped impatiently; I learned afterwards that my answer had not been satisfactory, had not been couched in the acceptable phrases of bitter, anti-Trotsky denunciation.

“I understand,” I said. “But I’ve never read Trotsky. What’s his stand on minorities?”

“Why ask me?” he asked. “I don’t read Trotsky.”

“Look,” I said. “If you found me reading Trotsky, what would that mean to you?”

“Comrade, you don’t understand,” he said in an annoyed tone.

That ended the conversation. But that was not the last was not the last time I was to hear the phrase: “Comrade, you don’t understand.” I had not been aware of holding wrong ideas. I had not read any of Trotsky’s works; indeed, the very opposite had been true. It had been Stalin’s National and Colonial Question that had captured my interest.

Of all the developments in the Soviet Union, the way scores of backward peoples had been led to unity on a national scale was what had enthralled me. I had read with awe how the Communists had sent phonetic experts into the vast regions of Russia to listen to the stammering dialects of people oppressed for centuries by the tsars. I had made the first total emotional commitment of my life when I read how the phonetic experts had given these tongueless people a language, newspapers, institutions. I had read how these forgotten folk had been encouraged to keep their old cultures, to see in their ancient customs meaning and satisfactions as deep as those contained in supposedly superior ways of living. And I had exclaimed to myself how different this was from the way in which Negroes were sneered at in America.

Then what was the meaning of the warning I had received from the black Communist? Why was I a suspected man because I wanted to reveal the vast physical and spiritual ravages of Negro life, the profundity latent in these rejected people, the dramas as old as man and the sun and the mountains and the seas that were taking place in the poverty of black America? What was the danger in showing the kinship between the sufferings of the Negro and the sufferings of other people?

6

Isat one morning in Ross’s home with his wife and child. I was scribbling furiously upon my yellow sheets of paper. The doorbell rang and Ross’s wife admitted a black Communist, one Ed Green. He was tall, taciturn, soldierly, square-shouldered. I was introduced to him and he nodded stiffly.

“What’s happening here?” he asked stiffly.

Ross explained my project to him, and as Ross talked I could see Ed Green’s face darken. He had not sat down and when Ross’s wife offered him a chair he did not hear her.

“What’re you going to do with these notes?” he asked me.

“I hope to weave them into stories,” I said.

“What’re you asking the party members?”

“About their lives in general.”

“Who suggested this to you?” he asked.

“Nobody. I thought of it myself.”

“Were you ever a member of any other political group?”

“I worked with the Republicans once,” I said.

“I mean, revolutionary organizations?” he asked.

“No. Why do you ask?”

“What kind of work do you do?”

“I sweep the streets for a living.”

“How far did you go in school?”

“Through the grammar grades.”

“You talk like a man who went further than that,” he said.

“I’ve read books. I taught myself.”

“I don’t know,” he said, looking off.

“What do you mean?” I asked. “What’s wrong?”

“To whom have you shown this material?”

“I’ve shown it to no one yet.”

What was the meaning of his questions? Naïvely I thought that he himself would make a good model for a biographical sketch.

“I’d like to interview you next,” I said.

“I’m not interested,” he snapped.

His manner was so rough that I did not urge him. He called Ross into a rear room. I sat feeling that I was guilty of something. In a few minutes Ed Green returned, stared at me wordlessly, then marched out.

“Who does he think he is?” I asked Ross.

“He’s a member of the Central Committee,” Ross said.

“But why does he act like that?”

“Oh, he’s always like that,” Ross said uneasily.

There was a long silence.

“He’s wondering what you’re doing with this material,” Ross said finally.

I looked at him. He, too, had been captured by suspicion. He was trying to hide the fear in his face.

“You don’t have to tell me anything you don’t want to,” I said.

That seemed to soothe him for a moment. But the seed of doubt had already been planted. I felt dizzy. Was I mad? Or were these people mad?

“You see, Dick,” Ross’s wife said, “Ross is under an indictment. Ed Green is the representative of the International Labor Defense for the South Side. It’s his duty to keep track of the people he’s trying to defend. He wanted to know if Ross has given you anything that could be used against him in court.”

I was speechless.

“What does he think I am?” I demanded.

There was no answer.

“You lost people!” I cried, and banged my fist on the table.

Ross was shaken and ashamed. “Aw, Ed Green’s just supercautious,” he mumbled.

“Ross,” I asked, “do you trust me?”

“Oh yes,” he said uneasily.

We two black men sat in the same room looking at each other in fear. Both of us were hungry. Both of us depended upon public charity to eat and for a place to sleep. Yet we had more doubt in our hearts of each other than of the men who had cast the mold of our lives.

I continued to take notes on Ross’s life, but each successive morning found him more reticent. I pitied him and did not argue with him, for I knew that persuasion would not nullify his fears. Instead I sat and listened to him and his friends tell tales of Southern Negro experience, noting them down in my mind, not daring to ask questions for fear they would become alarmed.

In spite of their fears, I became drenched in the details of their lives. I gave up the idea of the biographical sketches and settled finally upon writing a series of short stories, using the material I had got from Ross and his friends, building upon it, inventing. I wove a tale of a group of black boys trespassing upon the property of a white man and the lynching that followed. The story was published in an anthology under the title of “Big Boy Leaves Home,” but its appearance came too late to influence the Communists who were questioning the use to which I was putting their lives.

My fitful work assignments from the relief officials ceased and I looked for work that did not exist. I borrowed money to ride to and fro on the club’s business. I found a cramped attic for my mother and aunt and brother behind some railroad tracks. At last the relief authorities placed me in the South Side Boys’ Club and my wages were just enough to provide a bare living for my family.

Then political problems rose to plague me. Ross, whose life I had tried to write, was charged by the Communist Party with “anti-leadership tendencies,” “class collaborationist attitudes,” and “ideological factionalism”—phrases so fanciful that I gaped when I heard them. And it was rumored that I, too, would face similar charges. It was believed that I had been politically influenced by him.

One night a group of black comrades came to my house and ordered me to stay away from Ross.

“But why?” I demanded.

“He’s an unhealthy element,” they said. “Can’t you accept a decision?”

“Is this a decision of the Communist Party?”

“Yes,” they said.

“If I were guilty of something, I’d feel bound to keep your decision,” I said. “But I’ve done nothing.”

“Comrade, you don’t understand,” they said. “Members of the party do not violate the party’s decisions.”

“But your decision does not apply to me,” I said. “I'll be damned if I’ll act as if it does.”

“Your attitude does not merit our trust,” they said.

I was angry.

“Look,” I exploded, rising and sweeping my arms at the bleak attic in which I lived. “What is it here that frightens you? You know where I work. You know what I earn. You know my friends. Now, what in God’s name is wrong?”

They left with mirthless smiles which implied that I would soon know what was wrong.

But there was relief from these shadowy political bouts. I found my work in the South Side Boys’ Club deeply engrossing. Each day black boys between the ages of eight and twenty-five came to swim, draw, and read. They were a wild and homeless lot, culturally lost, spiritually disinherited, candidates for the clinics, morgues, prisons, reformatories, and the electric chair of the state’s death house. For hours I listened to their talk of planes, women, guns, politics, and crime. Their figures of speech were as forceful and colorful as any ever used by English-speaking people. I kept pencil and paper in my pocket to jot down their word-rhythms and reactions. These boys did not fear people to the extent that every man looked like a spy. The Communists who doubted my motives did not know these boys, their twisted dreams, their all too clear destinies; and I doubted if I should ever be able to convey to them the tragedy I saw here.

7

Party duties broke into my efforts at expression. The club decided upon a conference of all the left-wing writers in the Middle West. I supported the idea and argued that the conference should deal with craft problems. My arguments were rejected. The conference, the club decided, would deal with political questions. I asked for a definition of what was expected from the writers—books or political activity. Both, was the answer. Write a few hours a day and march on the picket line the other hours.

The conference convened with a leading Communist attending as adviser. The question debated was: What does the Communist Party expect from the club? The answer of the Communist leader ran from organizing to writing novels. I argued that either a man organized or he wrote novels. The party leader said that both must be done. The attitude of the party leader prevailed and Left Front, for which I had worked so long, was voted out of existence.

I knew now that the club was nearing its end, and I rose and stated my gloomy conclusions, recommending that the club dissolve. My “defeatism,” as it was called, brought upon my head the sharpest disapproval of the party leader. The conference ended with the passing of a multitude of resolutions dealing with China, India, Germany, Japan, and conditions afflicting various parts of the earth. But not one idea regarding writing had emerged.

The ideas I had expounded at the conference were linked with the suspicions I had roused among the Negro Communists on the South Side, and the Communist Party was now certain that it had a dangerous enemy in its midst. It was whispered that I was trying to lead a secret group in opposition to the party. I had learned that denial of accusations was useless. It was painful to meet a Communist, for I did not know what his attitude would be.

Following the conference, a national John Reed Club congress was called. It convened in the summer of 1934 with left-wing writers attending from all states. But as the sessions got under way there was a sense of looseness, bewilderment, and dissatisfaction among the writers, most of whom were young, eager, and on the verge of doing their best work. No one knew what was expected of him, and out of the congress came no unifying idea.

As the congress drew to a close, I attended a caucus to plan the future of the clubs. Ten of us met in a Loop hotel room, and to my amazement the leaders of the clubs’ national board confirmed my criticisms of the manner in which the clubs had been conducted. I was excited. Now, I thought, the clubs will be given a new lease on life.

Then I was stunned when I heard a nationally known Communist announce a decision to dissolve the clubs. Why? I asked. Because the clubs do not serve the new People’s Front policy, I was told. That can be remedied; the clubs can be made healthy and broad, I said. No; a bigger and better organization must be launched, one in which the leading writers of the nation could be included, they said. I was informed that the People’s Front policy was now the correct vision of life and that the clubs could no longer exist. I asked what was to become of the young writers whom the Communist Party had implored to join the clubs and who were ineligible for the new group, and there was no answer. “This thing is cold!” I exclaimed to myself. To effect a swift change in policy, the Communist Party was dumping one organization, then organizing a new scheme with entirely new people!

I found myself arguing alone against the majority opinion and then I made still another amazing discovery. I saw that even those who agreed with me would not support me. At the meeting I learned that when a man was informed of the wish of the party he submitted, even though he knew with all the strength of his brain that the wish was not a wise one, was one that would ultimately harm the party’s interests.

It was not courage that made me oppose the party. I simply did not know any better. It was inconceivable to me, though bred in the lap of Southern hate, that a man could not have his say. I had spent a third of my life traveling from the place of my birth to the North just to talk freely, to escape the pressure of fear. And now I was facing fear again.

Before the congress adjourned, it was decided that another congress of American writers would be called in New York the following summer, 1935. I was lukewarm to the proposal and tried to make up my mind to stand alone, write alone. I was already afraid that the stories I had written would not fit into the new, official mood. Must I discard my plot-ideas and seek new ones? No. I could not. My writing was my way of seeing, my way of living, my way of feeling; and who could change his sight, his sense of direction, his senses?

8

The spring of 1935 came and the plans for the writers’ congress went on apace. For some obscure reason—it might have been to “save” me—I was urged by the local Communists to attend and I was named as a delegate. I got time off from my job at the South Side Boys’ Club and, along with several other delegates, hitchhiked to New York.

We arrived in the early evening and registered for the congress sessions. The opening mass meeting was being held at Carnegie Hall. I asked about housing accommodations, and the New York John Reed Club members, all white members of the Communist Party, looked embarrassed. I waited while one white Communist called another white Communist to one side and discussed what could be done to get me, a black Chicago Communist, housed. During the trip I had not thought of myself as a Negro; I had been mulling over the problems of the young left-wing writers I knew. Now, as I stood watching one white comrade talk frantically to another about the color of my skin, I felt disgusted. The white comrade returned.

“Just a moment, comrade,” he said to me. “I’ll get a place for you.”

“But haven’t you places already?” I asked. “Matters of this sort are ironed out in advance.”

“Yes,” He admitted in an intimate tone. “We have some addresses here, but we don’t know the people. You understand?”

“Yes, I understand,” I said, gritting my teeth.

“But just wait a second,” he said, touching my arm to reassure me. “I’ll find something.”

“Listen, don’t bother,” I said, trying to keep anger out of my voice.

“Oh, no,” he said, shaking his head determinedly. “This is a problem and I’ll solve it.”

“It oughtn’t to be a problem,” I could not help saying.

“Oh, I didn’t mean that,” he caught himself.

I cursed under my breath. Several people standing near-by observed the white Communist trying to find a black Communist a place to sleep. I burned with shame. A few minutes later the white Communist returned, frantic-eyed, sweating.

“Did you find anything?” I asked.

“No, not yet,” he said, panting. “Just a moment. I’m going to call somebody I know. Say, give me a nickel for the phone.”

“Forget it,” I said. My legs felt like water. “I’ll find a place. But I’d like to put my suitcase somewhere until after the meeting tonight.”

“Do you really think you can find a place?” he asked, trying to keep a note of desperate hope out of his voice.

“Of course I can,” I said.

He was still uncertain. He wanted to help me, but he did not know how. He locked my bag in a closet and I stepped to the sidewalk wondering where I would sleep that night. I stood on the sidewalks of New York with a black skin and practically no money, absorbed, not with the burning questions of the left-wing literary movement in the United States, but with the problem of how to get a bath. I presented my credentials at Carnegie Hall. The building was jammed with people. As I listened to the militant speeches, I found myself wondering why in hell I had come.

I went to the sidewalk and stood studying the faces of the people. I met a Chicago club member.

“Didn’t you find a place yet?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “I’d like to try one of the hotels, but, God, I’m in no mood to argue with a hotel clerk about my color.”

“Oh, hell, wait a minute,” he said.

He scooted off. He returned in a few moments with a big, heavy white woman. He introduced us.

“You can sleep in my place tonight,” she said.

I walked with her to her apartment and she introduced me to her husband. I thanked them for their hospitality and went to sleep on a cot in the kitchen. I got up at six, dressed, tapped on their door, and bade them good-bye. I went to the sidewalk, sat on a bench, took out pencil and paper, and tried to jot down notes for the argument I wanted to make in defense of the John Reed Clubs. But the problem of the clubs did not seem important. What did seem important was: Could a Negro ever live halfway like a human being in this goddamn country?

That day I sat through the congress sessions, but what I heard did not touch me. That night I found my way to Harlem and walked pavements filled with black life. I was amazed, when I asked passers-by, to learn that there were practically no hotels for Negroes in Harlem. I kept walking. Finally I saw a tall, clean hotel; black people were passing the doors and no white people in sight. Confidently I entered and was surprised to see a white clerk behind the desk. I hesitated.

“I’d like a room,” I said.

“Not here,” he said.

“But isn’t this Harlem?” I asked.

“Yes, but this hotel is for white only,” he said.

“Where is a hotel for colored?”

“You might try the Y,” he said.

Half an hour later I found the Negro Young Men’s Christian Association, that bulwark of Jim Crowism for young black men, got a room, took a bath, and slept for twelve hours. When I awakened, I did not want to go to the congress. I lay in bed thinking, “I’ve got to go it alone... I’ve got to learn how again...”

I dressed and attended the meeting that was to make the final decision to dissolve the clubs. It started briskly. A New York Communist writer summed up the history of the clubs and made a motion for their dissolution. Debate started and I rose and explained what the clubs meant to young writers and begged for their continuance. I sat down amid silence. Debate was closed. The vote was called. The room filled with uplifted hands to dissolve. Then came a call for those who disagreed and my hand went up alone. I knew that my stand would be interpreted as one of opposition to the Communist Party, but I thought: “The hell with it.”

9

With the john reed clubs now dissolved, I was free of all party relations. I avoided unit meetings for fear of being subjected to discipline. Occasionally a Negro Communist—defying the code that enjoined him to shun suspect elements—came to my home and informed me of the current charges that Communists were bringing against one another. To my astonishment I heard that Buddy Nealson had branded me a “smuggler of reaction.”

Buddy Nealson was the Negro who had formulated the Communist position for the American Negro; he had made speeches in the Kremlin; he had spoken before Stalin himself. “Why does Nealson call me that?” I asked.

“He says that you are a petty bourgeois degenerate,” I was told.

“What does that mean?”

“He says that you are corrupting the party with your ideas.”

“How?”

There was no answer. I decided that my relationship with the party was about over; I should have to leave it. The attacks were growing worse, and my refusal to react incited Nealson into coining more absurd phrases. I was termed a “bastard intellectual,” “an incipient Trotskyite”; it was claimed that I possessed an anti leadership attitude and that I was manifesting “seraphim tendencies”—a phrase meaning that one has withdrawn from the struggle of life and considers oneself infallible.

Working all day and writing half the night brought me down with a severe chest ailment. While I was ill, a knock came at my door one morning. My mother admitted Ed Green, the man who had demanded to know what use I planned to make of the material I was collecting from the comrades. I stared at him as I lay abed and I knew that he considered me a clever and sworn enemy of the party. Bitterness welled up in me.

“What do you want?” I asked bluntly. “You see I’m ill.”

“I have a message from the party for you,” he said.

I had not said good day, and he had not offered to say it. He had not smiled, and neither had I. He looked curiously at my bleak room.

“This is the home of a bastard intellectual,” I cut at him.

He stared without blinking. I could not endure his standing there so stone like. Common decency made me say, “Sit down.”

His shoulders stiffened.

“I’m in a hurry.” He spoke like an army officer.

“What do you want to tell me?”

“Do you know Buddy Nealson?” he asked.

I was suspicious. Was this a political trap?

“What about Buddy Nealson?” I asked, committing myself to nothing until I knew the kind of reality I was grappling with.

“He wants to see you,” Ed Green said.

“What about?” I asked, still suspicious.

“He wants to talk with you about your party work,” he said.

“I’m ill and can’t see him until I’m well,” I said.

Ed Green stood for a fraction of a second, then turned on his heel and marched out of the room. When my chest healed, I sought an appointment with Buddy Nealson. He was a short, black man with an ever ready smile, thick lips, a furtive manner, and a greasy, sweaty look. His bearing was nervous, self-conscious; he seemed always to be hiding some deep irritation. He spoke in short, jerky sentences, hopping nimbly from thought to thought, as though his mind worked in a free, associational manner. He suffered from asthma and would snort at unexpected intervals. Now and then he would punctuate his flow of words by taking a nip from a bottle of whiskey. He had traveled half around the world and his talk was pitted with vague allusions to European cities. I met him in his apartment, listened to him intently, observed him minutely, for I knew that I was facing one of the leaders of World Communism.

“Hello, Wright,” he snorted. “I’ve heard about you.”

As we shook hands he burst into a loud, seemingly causeless laugh; and as he guffawed I could not tell whether his mirth was directed at me or was meant to hide his uneasiness.

“I hope what you’ve heard about me is good,” I parried.

“Sit down,” he laughed again, waving me to a chair. “Yes, they tell me you write.”

“I try to,” I said.

“You can write,” he snorted. “I read that article you wrote for the New Masses about Joe Louis. Good stuff. First political treatment of sports we’ve yet had. Ha-ha.”

I waited. I had thought that I should encounter a man of ideas, but he was not that. Then perhaps he was a man of action? But that was not indicated either.

“They tell me that you are a friend of Ross,” he shot at me.

I paused before answering. He had not asked me directly, but had hinted in a neutral, teasing way. Ross, I had been told, was slated for expulsion from the party on the ground that he was “ anti leadership”; and if a member of the Communist International was asking me if I was a friend of a man about to be expelled, he was indirectly asking me if I was loyal or not.

“Ross is not particularly a friend of mine,” I said frankly. “But I know him well; in fact, quite well.”

“If he isn’t your friend, how do you happen to know him so well?” he asked, laughing to soften the hard threat of his question.

“I was writing an account of his life and I know him as well, perhaps, as anybody,” I told him.

“I heard about that,” he said. “Wright. Ha-ha. Say, let me call you Dick, hunh?”

“Go ahead,” I said.

“Dick,” he said, “Ross is a nationalist.” He paused to let the weight of his accusation sink in. He meant that Ross’s militancy was extreme. “We Communists don’t dramatize Negro nationalism,” he said in a voice that laughed, accused, and drawled.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“We’re not advertising Ross.” He spoke directly now.

“We’re talking about two different things,” I said. “You seem worried about my making Ross popular because he is your political opponent. But I’m not concerned about Ross’s politics at all. The man struck me as one who typified certain traits of the Negro migrant. I’ve already sold a story based upon an incident in his life.”

Nealson became excited.

“What was the incident?” he asked.

“Some trouble he got into when he was thirteen years old,” I said.

“Oh, I thought it was political,” he said, shrugging.

“But I’m telling you that you are wrong about that,” I explained. “I’m not trying to fight you with my writing. I’ve no political ambitions. You must believe that. I’m trying to depict Negro life.”

“Have you finished writing about Ross?”

“No,” I said. “I dropped the idea. Our party members were suspicious of me and were afraid to talk.” He laughed.

“Dick,” he began, “we’re short of forces. We’re facing a grave crisis.”

“The party’s always facing a crisis,” I said.

His smile left and he stared at me.

“You’re not cynical, are you, Dick?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “But it’s the truth. Each week, each month there’s a crisis.”

“You’re a funny guy,” he said, laughing, snorting again. “But we’ve got a job to do. We’re altering our work. Fascism’s the danger, the danger now to all people.”

“I understand,” I said.

“We’ve got to defeat the Fascists,” he said, snorting from asthma. “We’ve discussed you and know your abilities. We want you to work with us. We’ve got to crash out of our narrow way of working and get our message to the church people, students, club people, professionals, middle class.”

“I’ve been called names,” I said softly. “Is that crashing out of the narrow way?”

“Forget that,” he said.

He had not denied the name-calling. That meant that, if I did not obey him, the name-calling would begin again.

“I don’t know if I fit into things,” I said openly.

“We want to trust you with an important assignment,” he said.

“What do you want me to do?”

“We want you to organize a committee against the high cost of living.”

“The high cost of living?” I exclaimed. “What do I know about such things?”

“It’s easy. You can learn,” he said.

I was in the midst of writing a novel and he was calling me from it to tabulate the price of groceries. “He doesn’t think much of what I’m trying to do,” I thought.

“Comrade Nealson,” I said, “a writer who hasn’t written anything worth while is a most doubtful person. Now, I’m in that category. Yet I think I can write. I don’t want to ask for special favors, but I’m in the midst of a book which I hope to complete in six months or so. Let me convince myself that I’m wrong about my hankering to write and then I’ll be with you all the way.”

“Dick,” he said, turning in his chair and waving his hand as though to brush away an insect that was annoying him, “you’ve got to get to the masses of people.”

“You’ve seen some of my work,” I said. “Isn’t it just barely good enough to warrant my being given a chance?”

“The party can’t deal with your feelings,” he said.

“Maybe I don’t belong in the party,” I stated it in full.

“Oh, no! Don’t say that,” he said, snorting. He looked at me. “You’re blunt.”

“I put things the way I feel them,” I said. “I want to start in right with you. I’ve had too damn much crazy trouble in the party.”

He laughed and lit a cigarette.

“Dick,” he said, shaking his head, “the trouble with you is that you’ve been around with those white artists on the North Side too much. You even talk like ’em. You’ve got to know your own people.”

“I think I know them,” I said, realizing that I could never really talk with him. “I’ve been inside of three fourths of the Negroes’ homes on the South Side.”

“But you’ve got to work with ’em,” he said.

“I was working with Ross until I was suspected of being a spy,” I said.

“Dick,” he spoke seriously now, “the party has decided that you are to accept this task.”

I was silent. I knew the meaning of what he had said. A decision was the highest injunction that a Communist could receive from his party, and to break a decision was to break the effectiveness of the party’s ability to act. In principle I heartily agreed with this, for I knew that it was impossible for working people to forge instruments of political power until they had achieved unity of action. Oppressed for centuries, divided, hopeless, corrupted, misled, they were cynical—as I had once been—and the Communist method of unity had been found historically to be the only means of achieving discipline. In short, Nealson had asked me directly if I were a Communist or not. I wanted to be a Communist, but my kind of Communist. I wanted to shape people’s feelings, awaken their hearts. But I could not tell Nealson that; he would only have snorted.

“I’ll organize the committee and turn it over to someone else,” I suggested.

“You don't want to do this, do you?” he asked.

“No,” I said firmly.

“What would you like to do on the South Side, then?”

“I’d like to organize Negro artists,” I said.

“But the party doesn’t need that now,” he said.

I rose, knowing that he had no intention of letting me go after I had organized the committee. I wanted to tell him that I was through, but I was not ready to bring matters to a head. I went out, angry with myself, angry with him, angry with the party. Well, I had not broken the decision, but neither had I accepted it wholly. I had dodged, trying to save time for writing, time to think.

10

My task consisted in attending meetings until the late hours of the night, taking part in discussions, or lending myself generally along with other Communists in leading the people of the South Side. We debated the housing situation, the best means of forcing the city to authorize open hearings on conditions among Negroes. I gritted my teeth as the daily value of pork chops was tabulated, longing to be at home with my writing.

Nealson was cleverer than I and he confronted me before I had a chance to confront him. I was summoned one night to meet Nealson and a “friend.” When I arrived at a South Side hotel I was introduced to a short, yellow man who carried himself like Napoleon. He wore glasses, kept his full lips pursed as though he were engaged in perpetual thought. He swaggered when he walked. He spoke slowly, precisely, trying to charge each of his words with more meaning than the words were able to carry. He talked of trivial things in lofty tones. He said that his name was Smith, that he was from Washington, that he planned to launch a national organization among Negroes to federalize all existing Negro institutions so as to achieve a broad unity of action. The three of us sat at a table, facing one another. I knew that another and last offer was about to be made to me, and if I did not accept it, there would be open warfare.

“Wright, how would you like to go to Switzerland?” Smith asked with dramatic suddenness.

“I’d like it,” I said. “But I’m tied up with work now.”

“You can drop that,” Nealson said. “This is important.”

“What would I do in Switzerland?” I asked.

“You’ll go as a youth delegate,” Smith said. “From there you can go to the Soviet Union.”

“Much as I’d like to, I’m afraid I can’t make it,” I said honestly. “I simply cannot drop the writing I’m doing now.”

We sat looking at one another, smoking silently.

“Has Nealson told you how I feel?” I asked Smith.

Smith did not answer. He stared at me a long time, then spat: “Wright, you’re a fool!”

I rose. Smith turned away from me. A breath more of anger and I should have driven my fist into his face. Nealson laughed sheepishly, snorting.

“Was that necessary?” I asked, trembling.

I stood recalling how, in my boyhood, I would have fought until blood ran had anyone said anything like that to me. But I was a man now and master of my rage, able to control the surging emotions. I put on my hat and walked to the door. “Keep cool,” I said to myself. “Don’t let this get out of hand.”

“This is good-bye,” I said.

I attended the next unit meeting and asked for a place on the agenda, which was readily granted. Nealson was there. Evans was there. Ed Green was there. When my time came to speak, I said: —

“Comrades, for the past two years I’ve worked daily with most of you. Despite this, I have for some time found myself in a difficult position in the party. What has caused this difficulty is a long story which I do not care to recite now; it would serve no purpose. But I tell you honestly that I think I’ve found a solution of my difficulty. I am proposing here tonight that my membership be dropped from the party rolls. No ideological differences impel me to say this. I simply do not wish to be bound any longer by the party’s decisions. I should like to retain my membership in those organizations in which the party has influence, and I shall comply with the party’s program in those organizations. I hope that my words will be accepted in the spirit in which they are said. Perhaps sometime in the future I can meet and talk with the leaders of the party as to what tasks I can best perform.”

I sat down amid a profound silence. The Negro secretary of the meeting looked frightened, glancing at Nealson, Evans, and Ed Green.

“Is there any discussion on Comrade Wright’s statement?” the secretary asked finally.

“I move that discussion on Wright’s statement be deferred,” Nealson said.

A quick vote confirmed Nealson’s motion. I looked about the silent room, then reached for my hat and rose.

“I should like to go now,” I said.

No one said anything. I walked to the door and out into the night and a heavy burden seemed to lift from my shoulders. I was free. And I had done it in a decent and forthright manner. I had not been bitter. I had not raked up a single recrimination. I had attacked no one. I had disavowed nothing.

The next night two Negro Communists called at my home. They pretended to be ignorant of what had happened at the unit meeting. Patiently I explained what had occurred.

“Your story does not agree with what Nealson says,” they said, revealing the motive of their visit.

“And what does Nealson say?” I asked.

“He says that you are in league with a Trotskyite group, and that you made an appeal for other party members to follow you in leaving the party.”

“What?” I gasped. “That’s not true. I asked that my membership be dropped. I raised no political issues.” What did this mean? I sat pondering. “Look, maybe I ought to make my break with the party clean. If Nealson’s going to act this way, I’ll resign.”

“You can’t resign,” they told me.

“What do you mean?” I demanded.

“No one can resign from the Communist Party.” I looked at them and laughed.

“You’re talking crazy,” I said.

“Nealson would expel you publicly, cut the ground from under your feet if you resigned,” they said. “People would think that something was wrong if someone like you quit here on the South Side.”

I was angry. Was the party so weak and uncertain of itself that it could not accept what I had said at the unit meeting? Who thought up such tactics? Then, suddenly, I understood. These were the secret, underground tactics of the political movement of the Communists under the tsars of Old Russia! The Communist Party felt that it had to assassinate me morally merely because I did not want to be bound by its decisions. I saw now that my comrades were acting out a fantasy that had no relation whatever to the reality of their environment.

“Tell Nealson that if he fights me, then, by God, I’ll fight him,” I said. “If he leaves this damn thing where it is, then all right. If he thinks I won’t fight him publicly, he’s crazy!”

I was not able to know if my statement reached Nealson. There was no public outcry against me, but in the ranks of the party itself a storm broke loose and I was branded a traitor, an unstable personality, and one whose faith had failed.

My comrades had known me, my family, my friends; they, God knows, had known my aching poverty. But they had never been able to conquer their fear of the individual way in which I acted and lived, an individuality which life had seared into my bones.

11

Iwas transferred by the relief authorities from the South Side Boys’ Club to the Federal Negro Theater to work as a publicity agent. There were days when I was acutely hungry for the incessant analyses that went on among the comrades, but whenever I heard news of the party’s inner life, it was of charges and countercharges, reprisals and counterreprisals.

The Federal Negro Theater, for which I was doing publicity, had run a series of ordinary plays, all of which had been revamped to “Negro style,” with jungle scenes, spirituals, and all. For example, the skinny white woman who directed it, an elderly missionary type, would take a play whose characters were white, whose theme dealt with the Middle Ages, and recast it in terms of Southern Negro life with overtones of African backgrounds. Contemporary plays dealing realistically with Negro life were spurned as being controversial. There were about forty Negro actors and actresses in the theater, lolling about, yearning, disgruntled.

What a waste of talent, I thought. Here was an opportunity for the production of a worth-while Negro drama and no one was aware of it. I studied the situation, then laid the matter before white friends of mine who held influential positions in the Works Progress Administration. I asked them to replace the white woman—including her quaint aesthetic notions—with someone who knew the Negro and the theater. They promised me that they would act.

Within a month the white woman director had been transferred. We moved from the South Side to the Loop and were housed in a first-rate theater. I successfully recommended Charles DeSheim, a talented Jew, as director. DeSheim and I held long talks during which I outlined what I thought could be accomplished. I urged that our first offering should be a bill of three one-act plays, including Paul Green’s Hymn to the Rising Sun, a grim, poetical, powerful one-acter dealing with chain-gang conditions in the South.

I was happy. At last I was in a position to make suggestions and have them acted upon. I was convinced that we had a rare chance to build a genuine Negro theater. I convoked a meeting and introduced DeSheim to the Negro company, telling them that he was a man who knew the theater, who would lead them toward serious dramatics. DeSheim made a speech wherein he said that he was not at the theater to direct it, but to help the Negroes to direct it. He spoke so simply and eloquently that they rose and applauded him.

I then proudly passed out copies of Paul Green’s Hymn to the Rising Sun to all members of the company. DeSheim assigned reading parts. I sat down to enjoy adult Negro dramatics. But something went wrong. The Negroes stammered and faltered in their lines. Finally they stopped reading altogether. DeSheim looked frightened. One of the Negro actors rose.

“Mr. DeSheim,” he began, “we think this play is indecent. We don’t want to act in a play like this before the American public. I don’t think any such conditions exist in the South. I lived in the South and I never saw any chain gangs. Mr. DeSheim, we want a play that will make the public love us.”

“What kind of play do you want?” DeSheim asked them.

They did not know. I went to the office and looked up their records and found that most of them had spent their lives playing cheap vaudeville. I had thought that they played vaudeville because the legitimate theater was barred to them, and now it turned out they wanted none of the legitimate theater, that they were scared spitless at the prospects of appearing in a play that the public might not like, even though they did not understand that public and had no way of determining its likes or dislikes. I felt—but only temporarily—that perhaps the whites were right, that Negroes were children and would never grow up. DeSheim informed the company that he would produce any play they liked, and they sat like frightened mice, possessing no words to make known their vague desires.

When I arrived at the theater a few mornings later, I was horrified to find that the company had drawn up a petition demanding the ousting of DeSheim. I was asked to sign the petition and I refused.

“Don’t you know your friends?” I asked them.

They glared at me. I called DeSheim to the theater and we went into a frantic conference.

“What must I do?” he asked. “Take them into your confidence,” I said. “Let them know that it is their right to petition for a redress of their grievances.”

DeSheim thought my advice sound and, accordingly, he assembled the company and told them that they had a right to petition against him if they wanted to, but that he thought any misunderstandings that existed could be settled smoothly.

“Who told you that we were getting up a petition?” a black man demanded.

DeSheim looked at me and stammered wordlessly. “There’s an Uncle Tom in the theater!” a black girl yelled.

After the meeting a delegation of Negro men came to my office and took out their pocketknives and flashed them in my face.

“You get the hell off this job before we cut your bellybutton out!” they said.

I telephoned my white friends in the Works Progress Administration: “Transfer me at once to another job, or I’ll be murdered.”

Within twenty-four hours DeSheim and I were given our papers. We shook hands and went our separate ways.

I was transferred to a white experimental theatrical company as a publicity agent and I resolved to keep my ideas to myself, or, better, to write them down and not attempt to translate them into reality.

12

One evening a group of Negro Communists called at my home and asked to speak to me in strict secrecy. I took them into my room and locked the door.

“Dick,” they began abruptly, “the party wants you to attend a meeting Sunday.”

“Why?” I asked. “ I’m no longer a member.”

“That’s all right. They want you to be present,” they said.

“Communists don’t speak to me on the street,” I said. “Now, why do you want me at a meeting?”

They hedged. They did not want to tell me.

“If you can’t tell me, then I can’t come,” I said. They whispered among themselves and finally decided to take me into their confidence.

“Dick, Ross is going to be tried,” they said.

“For what?”

They recited a long list of political offenses of which they alleged that he was guilty.

“But what has that got to do with me?”

“If you come, you’ll find out,” they said.

“I’m not that naive,” I said. I was suspicious now. Were they trying to lure me to a trial and expel me? “This trial might turn out to be mine.”

They swore that they had no intention of placing me on trial, that the party merely wanted me to observe Ross’s trial so that I might learn what happened to “enemies of the working class.”

As they talked, my old love of witnessing something new came over me. I wanted to see this trial, but I did not want to risk being placed on trial myself.

“Listen,” I told them. “I’m not guilty of Nealson’s charges. If I showed up at this trial, it would seem that I am.”

“No, it won’t. Please come.”

“All right. But, listen. If I’m tricked, I’ll fight. You hear? I don’t trust Nealson. I’m not a politician and I cannot anticipate all the funny moves of a man who spends his waking hours plotting.”

Ross’s trial took place that following Sunday afternoon. Comrades stood inconspicuously on guard about the meeting hall, at the doors, down the street, and along the hallways. When I appeared, I was ushered in quickly. I was tense. It was a rule that once you had entered a meeting of this kind you could not leave until the meeting was over; it was feared that you might go to the police and denounce them all.

Ross, the accused, sat alone at a table in the front of the hall, his face distraught. I felt sorry for him; yet I could not escape feeling that he enjoyed this. For him, this was perhaps the highlight of an otherwise bleak existence.

In trying to grasp why Communists hated intellectuals, my mind was led back again to the accounts I had read of the Russian Revolution. There had existed in Old Russia millions of poor, ignorant people who were exploited by a few educated, arrogant noblemen, and it became natural for the Russian Communists to associate betrayal with intellectualism. But there existed in the Western world an element that baffled and frightened the Communist Party: the prevalence of self-achieved literacy. Even a Negro, entrapped by ignorance and exploitation,—as I had been,—could, if he had the will and the love for it, learn to read and to understand the world in which he lived. And it was these people that the Communists could not understand.

The trial began in a quiet, informal manner. The comrades acted like a group of neighbors sitting in judgment upon one of their kind who had stolen a chicken. Anybody could ask and get the floor. There was absolute freedom of speech. Yet the meeting had an amazingly formal structure of its own, a structure that went as deep as the desire of men to live together.

A member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party rose and gave a description of the world situation. He spoke without emotion and piled up hard facts. He painted a horrible but masterful picture of Fascism’s aggression in Germany, Italy, and Japan.

I accepted the reason why the trial began in this manner. It was imperative that here be postulated against what or whom Ross’s crimes had been committed. Therefore there had to be established in the minds of all present a vivid picture of mankind under oppression. And it was a true picture. Perhaps no organization on earth, save the Communist Party, possessed so detailed a knowledge of how workers lived, for its sources of information stemmed directly from the workers themselves.

The next speaker discussed the role of the Soviet Union as the world’s lone workers’ state—how the Soviet Union was hemmed in by enemies, how the Soviet Union was trying to industrialize itself, what sacrifices it was making to help workers of the world to steer a path toward peace through the idea of collective security.

The facts presented so far were as true as any facts could be in this uncertain world. Yet no one word had been said of the accused, who sat listening like any other member. The time had not yet come to include him and his crimes in this picture of global struggle. An absolute had first to be established in the minds of the comrades so that they could measure the success or failure of their deeds by it.

Finally a speaker came forward and spoke of Chicago’s South Side, its Negro population, their suffering and handicaps, linking all that also to the world struggle. Then still another speaker followed and described the tasks of the Communist Party of the South Side. At last, the world, the national, and the local pictures had been fused into one overwhelming drama of moral struggle in which everybody in the hall was participating. This presentation had lasted for more than three hours, but it had enthroned a new sense of reality in the hearts of those present, a sense of man on earth. With the exception of the church and its myths and legends, there was no agency in the world so capable of making men feel the earth and the people upon it as the Communist Party.

Toward evening the direct charges against Ross were made, not by the leaders of the party, but by Ross’s friends, those who know him best! It was crushing. Ross wilted. His emotions could not withstand the weight of the moral pressure. No one was terrorized into giving information against him. They gave it willingly, citing dates, conversations, scenes. The black mass of Ross’s wrongdoing emerged slowly and irrefutably. The moment came for Ross to defend himself. I had been told that he had arranged for friends to testify in his behalf, but he called upon no one. He stood, trembling; he tried to talk and his words would not come. The hall was as still as death. Guilt was written in every pore of his black skin. His hands shook. He held on to the edge of the table to keep on his feet. His personality, his sense of himself, had been obliterated. Yet he could not have been so humbled unless he had shared and accepted the vision that had crushed him, the common vision that bound us all together.

“Comrades,” he said in a low, charged voice, “I’m guilty of all the charges, all of them.”

His voice broke in a sob. No one prodded him. No one tortured him. No one threatened him. He was free to go out of the hall and never see another Communist. But he did not want to. He could not. The vision of a communal world had sunk down into his soul and it would never leave him until life left him. He talked on, outlining how he had erred, how he would reform.