|

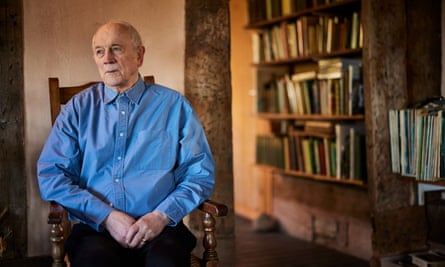

| ‘There will be something left undone’ … Garner at the Old Medicine House, which he saved from demolition; his new novel is called Treacle Walker. |

Alan Garner: ‘You don’t want to have a brilliant idea for a novel at the age of 87’

As the much-loved fantasy writer publishes yet another 'final’ novel – about a healer who can cure everything but jealousy – he talks about being made a pariah by Oxford and almost dying three times

Alison Flood

Monday 25 October 2021

Alan Garner has always feared unexpectedly dying before he finishes the book he’s working on. It means that this most beloved of writers – whose works feel chiselled from the Cheshire landscape of his home, and whose devoted fans range from Philip Pullman and Neil Gaiman to Margaret Atwood – keeps joking that he’s written his last book.

He did it when Boneland, the haunting sequel to his children’s novels The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath, was published in 2012. He did it when his childhood memoir, Where Shall We Run To?, came out in 2018. “Given that it takes me between five and nine years to write a novel,” he said at the time, “the joke runs a bit sour when you’re in your early 80s.” Three years later, having just turned 87, Garner has written Treacle Walker, a slice of myth and magic that only he could have produced, in which a young boy, Joe Coppock, is drawn into the world of “glamourie” – which sits alongside and within his own world – when a rag-and-bone man comes to his door.

|

| Alan Garner |

“This lifelong fear meant I did stupid things. In the days before computers, I carried the sole manuscript to The Owl Service around with me, and there’s nothing more dangerous than doing that,” says Garner, once his wife, Griselda, has sorted out his Zoom. “But a friend, who’s very cynical and very helpful, said I just have to come to terms with the fact that there will be something left undone. It’s OK to be scared in your 20s. But when you’re 87, and average nine years a book …”

In Treacle Walker, a spare, uncanny book, Joe exchanges a pair of pyjamas and a lamb’s shoulder blade for a near-empty jar of medicine and a donkey stone, a type of scouring block. Touching the remains of what’s left in the jar to his eye shifts the veil between the everyday and the strange – and he sees a man sit up in a bog to speak to him.

The new novel has its roots in a conversation Garner had in 2012 with his friend Bob Cywinski, a particle physicist. Cywinski had been quizzing Garner about where he got his ideas. “He’s dealing with questions arising from the observed universe, and I could not get across to him that I didn’t know where I got the ideas from, that they sort of emerged, and that bothered him.”

The next day, they were walking together across Castle Hill, an iron age hill fort in Huddersfield. “Just inconsequentially, Bob told me about a historical character, a local tramp called Walter Helliwell, known as Treacle Walker. He was a healer, claiming to be able to cure all things except jealousy. And I looked at Bob and said, ‘You remember last night? Well, just make a note that on the afternoon of Sunday 15 July 2012, you’ve given me an idea, and you’ve given me a book.”

What had snagged Garner’s attention was the original meaning of treacle: medicine. “But Walter Helliwell, a tramp, couldn’t have know that, and that was how I knew something was there.”

The idea had to “brew nebulously” for some time, derailed after Garner’s work on an oral history project with Manchester University prompted the fragmentary childhood memoir Where Shall We Run To?, elements from which appear in Treacle Walker. Garner’s contribution to the oral work was his memory of his grandfather’s account of the legend of Alderley Edge, in which a farmer sells his white mare to an old man who turns out to be a wizard and leads him to a sleeping army of knights inside the hill – the basis for Weirdstone. “It was his truth, a part of him, which he passed on,” writes Garner. “Here is how he told it. And it is the manner of the telling that is important.

“Doing the project, I found that talking to my contemporaries, we could all remember a given event, but when we compared notes, there were as many versions of that memory as there were people to remember it. And I realised that oral history was as unreliable as documentary history. At the end of the oral history, there were so many fragments lying around that were valuable, and hadn’t got in, so I swept them into a kind of mental file, and let them gestate. Then I heard a voice talking inside my head. And it was me. It was a complete reconstruction of childhood, and all I had to do was write it down, honestly, but not worry about the subjectivity of it all.”

Garner says the “historian in me” had always stopped him from wanting to write an autobiography. “It’s absolutely pretentious muck, and anyway, it’s only there to promote egos. But I found a reason for doing it, and so I just listened to the voice.”

Treacle Walker, meanwhile, had been “on the back hob, stewing”. “Having immersed myself in the childhood memories, and having talked to contemporaries of mine for the oral archive, I’d reopened a long-closed lexicon, and the speech rhythms were there in my head from my childhood. That gave me Where Shall We Run To? and then that gave me – not consciously, I’m being wise after the event – the format for Treacle Walker.”

Only after he’d finished writing the novel did he realise how much it drew from his own life, from the cry of the rag-and-bone man to the bits about Knockout comics. “A friend read the manuscript and said, ‘You’ve done it again – you’ve written your autobiography.’ Bob Cywinski gave me grief when I said, ‘I’m never going to write an autobiography.’ He said: ‘That’s because you’ve never written anything else.’ Who needs enemies!”

Garner has long been preoccupied with time. As a child, he suffered from three long illnesses – diptheria, meningitis and pneumonia – each bringing him close to death and confining him to bed for long periods. The ceiling he stared at became three-dimensional and time became elastic. “The ceiling had showed me that time was not simply a clock,” he writes in his 1997 collection of essays and talks, The Voice That Thunders. Treacle Walker opens with a quote from the Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli: “time is ignorance.” Garner says: “Rovelli was putting into scientific terms what I have known all my life. It’s a child’s view.”

Garner is a meticulous researcher. He took the time to learn Welsh while writing the Carnegie medal-winning The Owl Service, based on the mythical Welsh woman Blodeuwedd and adapted for a 1969 TV series. And he’s been chatting with Cywinski about whether it is theoretically possible for time to run backwards. “What quantum physics does show you is that we are modelling our universe in order to cope with it,” he says, “because there’s no such thing as now. Because you’re looking at me, and I’m looking at you, and we’re ruled by the speed of light, but that is also finite. And so I’m looking at you and you’re looking at me in the past.”

Joe Coppock’s home in Treacle Walker, and the chimney space where he and his tramp speak of important things, is a version of the Old Medicine House, a timber-framed building that was built about 450 years ago in Wrinehill in Staffordshire, and saved from demolition by the Garners after it fell into disrepair. They oversaw its disassembly and removal to Blackden in Cheshire, 20 miles away, where it was rebuilt and now sits alongside the Garner home near Alderley Edge, an area where Garners have lived since at least 1592 and where Alan and Griselda have been contentedly shielding during Covid times. “I have made it very difficult for the shields to be removed,” says Garner.

Treacle Walker is dedicated to “MGS”, which is Manchester Grammar School, at which Garner won a place by passing his 11-plus. It was an experience that would lead to Oxford (although he left without completing his classics degree) and also to alienation from his family and his community. “You become a pariah to your own family and a temporary gentleman to society,” says Garner. “There’s a dreadful isolation it produces, in the removal from a working-class background into an academic background. It leaves the individual stranded.”

Without Manchester Grammar School, however, Garner feels it is unlikely he would have written any of his novels, from Elidor and Red Shift to Thursbitch, Strandloper and Treacle Walker. “MGS is the point without which I would never have been able to write,” he says. “Joseph Coppock is the me I could have become if I’d not had the severe academic training that I did. Treacle Walker is what I could have become if I hadn’t jumped ship at Oxford and got off the road to academia.”

This time round, he has no intention of saying this is his last book. “I’m feeling just a slight queasiness,” he says. “I don’t want to have a brilliant idea at 87 – but I’m afraid there’s one tickling.”

No comments:

Post a Comment