|

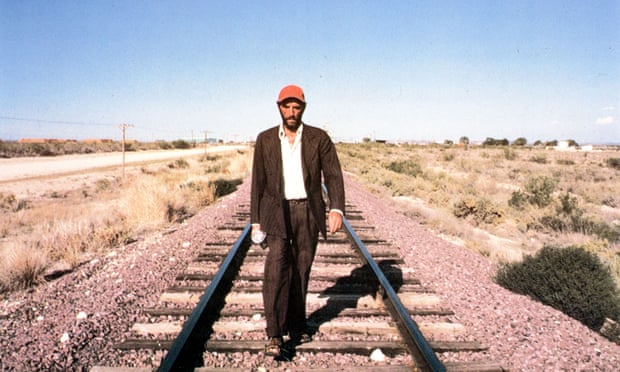

| ‘I made most of my fiction films as if they had been documentaries, then I made my documentaries as if they had been fictions’ … Wim Wenders. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi/The |

Wim Wenders: ‘When Paris, Texas won Cannes it was terrible’

The revered director talks about his friend Rainer Fassbinder, dealing with success and failure, and how he is like the angels in Wings of Desire – as a retrospective of his work comes to cinemas

Ryan Gilbey

Friday 1 July 2022

Is it bad manners to wear a Fassbinder T-shirt to an interview with Wim Wenders? Apparently not. “Ah, Rainer!” says Wenders, full of jubilation as he claps eyes on my wardrobe choice. Then he grits his teeth and snarls: “I’m still so fucking mad at him for dying.”

We are in the London offices of the distributor Curzon, which is releasing restored versions of eight of Wenders’ films in cinemas. Included is the Palme d’Or-winning 1984 masterpiece Paris, Texas and the 1987 fantasy Wings of Desire, in which angels watch over a divided Berlin. The 76-year-old director sports a silver quiff, his inquisitive eyes sparkling behind blue-framed spectacles. His own T-shirt, worn under a white shirt and braces, bears the image of a pair of red-and-blue anaglyph 3D glasses; he pulls his shirt open, like Superman showing off the “S” on his chest, so I can see it. He remains a cheerleader for 3D, having shot several of his own films in the format – most notably Pina, his ravishing 2011 documentary about the choreographer Pina Bausch, in which dance spills off the stage and on to streets, parks, public transport.

As we repair to a conference room, Wenders thinks back to the day in June 1982 when he heard that Fassbinder, his hard-living friend and contemporary, had died aged 37. “I was leaving the station in Munich early in the morning after getting off the night train. I saw the headlines, then I sat on the station steps and cried like a baby for 10 minutes.” He gives a sigh. “Rainer worked himself to death. I was angry at him when I realised the amount of sleeping pills and uppers and downers he had taken. Anybody could have told him he couldn’t go on like that for ever.”

Though dissimilar from one another in style, Wenders, Fassbinder and Werner Herzog spearheaded the German cinematic revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s. “When we started out, German cinema was dead. There was no industry that would have supported us. It was our mutual support that enabled us to continue. Not one of us was known in our own country until we all came back with reviews from London, New York or Paris. You had to be acclaimed somewhere else first.”

A surgeon’s son from Düsseldorf, Wenders studied medicine then philosophy before ending up at film school in Munich. His graduation film, Summer in the City (1971), has a Kinks-heavy soundtrack and a style straight from John Cassavetes: “My great hero then.” Next came The Goalkeeper’s Fear of the Penalty (AKA The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick), which he describes as “Hitchcock without the suspense”. An adaptation of The Scarlet Letter was not merely a misstep but a final straw. “I had no talent for costume movies. It was a poor man’s David Lean. I had made three films which owed their style to the cinema I liked. I said: ‘I’m going to give it all up. If that’s film-making, I don’t want to do it any more.’”

From that crisis emerged Alice in the Cities, his 1974 film about a writer put in charge of a precocious young girl. The picture begins with the camera gazing up at a plane passing overhead, and ends with a shot looking down on a train threading through the countryside. In between, Wenders established a new kind of road movie, characterised by a photographer’s eye and a rock’n’roller’s heart. Cool, wry, disaffected but playful, its influence endures today; the recent C’mon C’mon, starring Joaquin Phoenix, is practically a remake.

Wenders hit the road without a script, shooting on the hoof as he trekked with his actors from New York to Amsterdam and on to Wuppertal and towards Munich. “I shot it in chronological order while we were travelling, and it made all the difference. I was a fish in my own water and no longer in somebody else’s tank. I always think of Alice in the Cities as my first film because it was the first one where I was purely myself.” The experience was so satisfying that he and his cinematographer, Robby Müller, repeated it immediately with Wrong Move and Kings of the Road. “I thought: ‘Why do anything else if it’s so good to be doing this?’”

He named his production company Road Movies, and road movie elements survive even in Paris, Texas, though that film is essentially a languid take on the western (Wenders’ most beloved genre) and especially The Searchers. Harry Dean Stanton, swapping John Wayne’s Stetson for a battered red baseball cap, is the loner who emerges from the desert, tracks down a “stolen” woman (in this case, his estranged wife, working in a peep show and hauntingly played by Nastassja Kinski), then vanishes back into the wild again, just as Wayne did before him.

The protagonist of Alice in the Cities, played by Rüdiger Vogler, is a Polaroid enthusiast (as Wenders would soon become) and that film’s first line of dialogue is directed at him by a child on a bicycle: “Hey mister, what you taking those pictures for?” I put the same question to Wenders: why does he make these movies? “I try to be a witness to something,” he replies. “I try to preserve what I see. There’s a sense of preservation in my films from the beginning: of landscapes, houses, characters. The act of filming is so precious. The photographer – myself – will be gone one day, but the photo is still there.”

He describes Wings of Desire, shot three years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, as “a sheer document of a city that does not exist any more”. His sense of preservation was at its keenest, however, in the hit documentary Buena Vista Social Club, which celebrates a group of elderly Cuban musicians re-introduced to the world by Ry Cooder, composer of the plangent, twanging score to Paris, Texas.

“My film-making from the beginning had a huge documentary aspect,” he explains. “Looking back now, I think I made most of my fiction films – especially Alice and Kings of the Road – as if they had been documentaries, and then I made my documentaries as if they had been fictions.” How so? “Well, Buena Vista Social Club is a fairytale. These guys were cleaning shoes in Havana when Ry first called them. They had nothing; they were poor. By the end, when they’re playing Carnegie Hall and everyone is standing on their seats to applaud them, they’re the Beatles. If you wanted to write and direct it as fiction, it would be the same movie.”

The memorialising has naturally grown more acute with the passing of time. “It was so painful with Buena Vista Social Club because within a few years, they were all gone,” he says, his voice falling to a whisper. It’s a feeling he has had to get used to as, one by one, many of the actors in his films have died. Most recently it was William Hurt, star of Wenders’ science-fiction odyssey Until the End of the World. Before him, it was Stanton and Dean Stockwell, the onscreen brothers from Paris, Texas, and Bruno Ganz, who played the reluctant assassin in The American Friend and the angel who becomes human in Wings of Desire and its sequel, Faraway, So Close! Gone, too, is Solveig Dommartin, the trapeze artist for whom Ganz surrenders his divinity.

Wenders smiles fondly when he thinks of Peter Falk, the Columbo star and Cassavetes favourite, who was parachuted into Wings of Desire at the last minute to play himself after Wenders and the assistant director, Claire Denis (soon to become an auteur in her own right), realised that the picture needed a dash of humour. “What a lively man he was. I filmed a lot of people who are no longer with us, because I started early and shot with some old men in between. If you see them now, you can’t help but realise they are very much still alive on the screen. It is one of the capacities of cinema: to immortalise.”

Wings of Desire won him the best director prize at Cannes, but not all his memories related to that festival are happy ones. For years, Spike Lee raged against Wenders, who in his capacity as president of the jury in 1989 had awarded the Palme d’Or to Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape rather than to Lee’s Do the Right Thing. That hatchet is now buried – Lee told CNN in 2018 that it was “long forgotten. Mr Wenders is a great, great film-maker. Peace and love.” But Wenders knows only too well what it’s like to sweat over a movie and then see it go cruelly unappreciated.

Buena Vista Social Club, Pina and The Salt of the Earth (his documentary about the photographer Sebastião Salgado) have all been Oscar-nominated, whereas his recent fiction films – such as Palermo Shooting with Dennis Hopper, Don’t Come Knocking with Sam Shepard and Jessica Lange, Land of Plenty with Michelle Williams, and the 3D drama Every Thing Will Be Fine, starring James Franco and Charlotte Gainsbourg – have had all the impact of tumbleweed in a western.

Has he experienced any Spike Lee-esque feelings of anger and frustration? “Yes, that happened to me with Palermo Shooting,” he says with a grimace. “It was shown on the last day of Cannes. The critics were all tired and wasted. It was blown to pieces; it never had a chance. Don’t Come Knocking was treated the same way. But I’ve had films welcomed with open arms, so who am I to complain?” It’s not as if success is straightforward. When Paris, Texas won at Cannes, he says: “It was terrible afterwards. It created a huge void in my life for the next three years because everybody expected me to do that all over again, and that was the only thing I didn’t want to do.”

Why hasn’t his recent fiction cinema connected with people? “Some films are ahead of their time,” he says. “Others are too late. It’s such a tricky thing. Sometimes they never connect.” In the latter category, he puts his wacky comedy-drama The Million Dollar Hotel, co-written by Bono and starring Mel Gibson as a straight-arrow FBI agent. The movie’s prospects were hardly boosted when Gibson called it “as boring as a dog’s ass”.

“Oh, Mel killed the film,” Wenders agrees. “He’s very, very good in it. And he thought so. But his next project was What Women Want, and his own people said: ‘If you want to really kill What Women Want then show Million Dollar Hotel – it’s not helping you.’ He decided to turn against the film. It didn’t survive the blow.”

At least Wenders can look at the films he has made since Alice in the Cities, whether they have been loved, loathed or overlooked, and know that they are truly his. That goes even for Until the End of the World, originally released in 1991 in a contractually demanded three-hour edit (which he calls “the Reader’s Digest cut”) but now available in a version nearer to five. Watching his back catalogue, as audiences will be able to do more easily when a comprehensive Blu-ray box set arrives later this year, the films blur and bleed fruitfully into one another. The monorail in Wuppertal plays an integral role in Alice in the Cities and Pina, while Bausch’s dancers, performing in open spaces but ignored by a blase public, resemble the angels in Wings of Desire mingling with an oblivious populace.

As they compare their affectionate notes and observations on humanity, these angels seem like nothing so much as onscreen surrogates for the director himself: compassionate, curious, ever-watchful. Does he feel any kinship with them? “I feel a lot of kinship. I feel like the way they looked at us and the city and other people was very much the way I approach film-making.” Which is? He smiles: “With a loving look.”

Kino Dreams: A Wim Wenders Retrospective is in cinemas now

No comments:

Post a Comment