Even my mother thinks I should. When I called to tell her of the latest disaster, she sighed and said, Maybe, darling, you should give up on all that. Maybe it’s just time.

Okay, I’ve got other loves, after all. My broken-down mother. My blind old cat. A love poet who’s been dead two thousand years whose words I’m being paid to translate. A friend or two via text.

Who needs more?

Every morning I arise full of vim, crawl around wiping up Buster’s puddles, slip thyroid and seizure pills into his food, and re-diaper his skinny black haunches. Then I put on my faded polka-dot bikini and ride the elevator down twenty-one floors to swim twenty laps in the hourglass pool, ride back up, translate thirty lines of Latin, ride back down to walk three miles, then drink a solo toast or two to chalk up another day done.

Living in paradise: That’s me!

The air rolls in molten waves over your skin when you slide open the balcony door and dip out a hand, glass and tiles so hot they hurt. But how could your heart not flood with joy when you go out to walk on the blistering pink concrete and behold the hot white sky and hot green grass and flowers so red they flame your eyes and all that milky-green water?

I’ve found that if I put off the day’s walk until the last hour before sunset and carry a palm frond angled right, I can ward off the worst of the sun’s late rays that are bent on age-mottling my chest. And if I angle it higher I can also avoid the looks of those walking past who are amused by my freakishness. Why be in Miami if I don’t like the sun?

Yeah, well. Some of us just washed up where we did after random travels concerning men. Providence, Washington, Deutschland.

As I walked toward the sunset this evening, those men bobbed around in my head. Lurch, Eclipse-Eye, the Devil, Sir Gold. Also, a husband.

Gone, gone!

Erotic love: what a concept.

I walked along the Venetian Causeway toward the drawbridge, milky green swells of the bay all around. Young people displayed their lovely bright or dark flesh as they ran, cycled, or skated past. The man whose arms and chest are dense with blue tattoos ran by; he had earbuds in and panted too violently: couldn’t hear how loud he was, I guess. A woman jogged past in super-short shorts, with model legs and designer breasts and braided black hair that swung like beads. A man peddled near and wobbled wild when he got to her, yowling at her behind.

Yo mami mami mami!

Mamacita!

Ai.

Looked down at my own legs and realized that I don’t live anywhere near the zone of that woman anymore.

Yet once upon a time, when I was maybe fifteen, I didn’t even want to be seen by anyone, and all the same, out I walked, and honks, shouts, maybe even a crash as I passed!

Now, not so much.

I walked on toward the sunset, counting steps. I understand that counting’s a symptom of something, but why should knowing this stop me? The number of steps, boats, balconies, strokes, men, lines of Latin, pages.

Also, I suddenly thought, days since I’ve had sex.

Doesn’t matter if your mind ponders retiring from love: Mr. Body still makes trouble.

Thirty-two days is the answer. Since Sir Gold shattered my heart.

I doubt solitary pleasuring counts as sex.

What about atrophy? Does it count against that?

A word my mother whispered to me once. She’d been at the gynecologist’s, and when he stepped outside she swiveled her chart: vaginal atrophy, in his blue ink.

Started doing Kegels as I walked. Something new to count. Now this would be a full-body workout: FitFlops for legs and behind, arm-circling to fight the tender dewlaps hinting from my upper arms, Kegels for submarine muscles. I found it easiest to time the squeezes with cracks in the pink sidewalk. Hold tight for ten cracks, release for four, tight for ten, and take it to the bridge.

In the middle of the bay flows a quick current of sea that looks like a pale green river. Always something floating in it: coconut, tennis ball, palm frond. I always study the coconuts tumbling in the water, hoping one’s actually a head. No. Ditto palm fronds vis-à-vis shark fin. No. Everything ordinary, ordinary.

But on the other side of the drawbridge, on the grass near the water, was that strange duck I’ve seen there twice. What, did it live there? Alone on a skinny green verge between water and road? Solo silhouette, gazing north toward the bay, looking somehow noble. I walked toward it stealthily over the grass, but my FitFlops thwapped, and the duck startled and fluttered away. But did not fly—could not fly? No, one wing was clipped. It flapped into a sea-grape shrub and huddled in the leaves.

Stranded? On a strip between salt water and road? Not so bad at night, but cento per cento hell in the sun. Surely it ate grass. Mosquitoes? But it looked so thin, and what about fresh water? I had my water bottle and found a curved leaf, walked gingerly over to the duck, who was waddling backward deeper into the shrub. I poured water on the leaf, set it down, backed away. After a minute it poked out its black-and-pink-barnacled head and slurped.

Thirsty! Stranded. Desperate! And maybe it didn’t eat grass: It plucked a blade and let it droop listlessly from its beak, blinking at me with a sad black-bead eye.

I walked full of fervor back home. Rescue and relocate? Bring water every day? Food. What sort? Seeds?

A thudding came alongside me, an all-but-naked young man, not too tall and nicely fleshed, skin glistening wet. He was so close, I could feel that slippery skin in my hands and I could taste it on my tongue all the way up that lissome sleek back to his young neck, and then around his throat and up over the chin to lips I’d part—his glance fell on me as he thudded past, then it slid away.

So how’s the glam life down there? texted one of the old disastrous men, the Devil, as I was researching Muscovy ducks.

Super glam! Lots of fun poolside. Bikini getting action!

Happy times for you. Hope you fucking find what you want.

Darling, wrote my mother, doing fun things? Seeing friends?

This morning, after I’d swum and had begun translating Latin on a lounge chair by the pool, my neighbor N came wandering over—N, that odd bony woman with white-blond hair who looks like a cross between my mother and me. A wet animate skeleton in a bikini, hands and head too large, she stood above me in a towel and white hat.

Can I ask you a question? But wait, she said with her husky New York voice. Didn’t I see you on the causeway last night, over by the water? Sort of … squatting? It was almost dark. What were you doing? I hate to say what it looked like. I told P you were not the type to do that on the causeway.

Do what? No. Who’s P?

My chaperone.

What?

Just kidding. My husband. So what were you doing? You looked very furtive.

There’s this duck, I said and told N about her.

Really? she said. She’s stranded?

And alone, which doesn’t seem right.

No, N said, tilting her head. How do you know it’s a she?

She’s smaller and warbles, which is what they say the females do.

Well, it’s very concerning that she’s stranded, N said. What will she do for fresh water?

Exactly what’s worrying me.

Well. Maybe we should try to do something.

I plan to bring water every day. And Grape-Nuts. I can’t walk by and see her helpless like that. She’s getting thin.

N looked at me for a time, her eyes like deep pools: You could almost see something swimming inside them.

I think that’s good, she said. I think that’s good of you. You care for creatures that need care. This is important for people to do. And when I walk on the causeway, I’ll also bring her water.

But what I really want to do, I said, is transport her to a place with other ducks.

N considered me again.

Well, that sounds like the right thing. Yes.

But I think it’ll take more than one person. She’s skittish and waddles fast.

N’s expression went cloudy. So … you want help? You do. Oh, she said, oh, no. I can’t. I mean of course I want to. I love animals. But any kind of running and quick bending … I can’t. I have this … oh, it’s too boring. I have a lot of pain.

She shook her head and put up a hand before I could ask. No no no, she said, it’s not worth talking about. Bad surgery, that sort of thing. But anyway.

I’m sorry, I said.

Well. She unfolded her long bony legs and stood Pilates straight, ribs looking beached, in her tiny bikini. But she didn’t walk away. She took off her hat and turned back to me as I sat with the dampening book in my lap.

But that wasn’t my question, she said, about you and the duck. Do you mind? It’s none of my business. I don’t want to pry. But I can’t help it. So if I might ask …

Yes?

Well, you seem to be by yourself all the time, and I’m wondering, isn’t there someone in your life?

The lounge chair was soggy from overnight rain, and wet had seeped into my towel and gone cold. I put my hands on the Latin and thought, For fuck’s sake. Then looked up at her brightly.

Not just now, I said. But I’ve got Ovid!

She smiled the slow, sad smile. Okay, she said. You have Ovid. And the cat in diapers. And the duck. Those are your loves. Okay. Maybe that’s all you need. Who knows?

And she laughed her strange, dry laugh and unfolded her limbs and wandered away, that white-blond hair like a halo.

The next evening I brought a dish to fill from my water bottle, as well as a baggie of Grape-Nuts. Set dish near the duck’s shrub and strewed cereal near my feet. She looked at this but didn’t move. So I stepped back, and after a moment she waddled out of her shrub, first pecked cautiously at the nuggets, then gobbled. I crouched and watched. When I thought I might just touch her black-barnacled head and reached, she shivered and scooted off fast. Left her searching for nuggets in the grass and walked the Venetian.

I was out on my balcony translating and looking up now and then to the ionic blue sky when suddenly water splashed my table and arm. Not in the corner where it had drizzled last time and where I’d set the corn plant I found in the trash room and rescued—and this after twice asking the lady up there to please keep her water to herself.

I slapped shut the laptop, glared at the balcony above, went inside, stalked through my apartment and down the hall, took the stairs two at a time, and knocked on the door of that lady: silence. Went back downstairs, wrote a note, ran back up, and slid it under her door, panicking that she’d swing open the door just then and charge me with cowardice. As I hustled back down the hall, N rounded the corner.

Well hi, she said. Were you coming to see me?

Told her about the water woman.

She seems nice, N said. She does have a lovely garden on her balcony. But I can understand how annoying that must be. Why don’t you come in. Have some coffee.

N’s apartment, on the other side of the building from mine, looks over the pool and dock and brilliant blue bay, Monument Island, the city, the ships.

Tried touching the duck last night, I said.

No luck?

She’s fast. I gave her Grape-Nuts, put them near my foot, and she came over and bobbed for a minute, then started to eat, and I was sure I could grab her, but no. She waddled off and dropped into the bay. But even if she got to Rivo Alto, I doubt any ducks are there, either. Or fresh water, except maybe somebody’s pool. What I realized then is that someone else is leaving her food: by her shrub was a dish of cat food. Cat food.

That can’t be very good for her.

It’s disgusting. Whoever it was left an empty bottle, too, actually a few.

Just tossed?

It looks like they might have brought her water and then left the bottles. So I’m going to put a note in one.

N looked at me. A message in a bottle?

Saying We need to save this duck! and giving my number.

Well, said N, it’ll certainly be interesting to see if anyone responds.

I’m hopeful.

Now this duck is intriguing, she said, but to tell the truth I’d rather know a little more about other things.

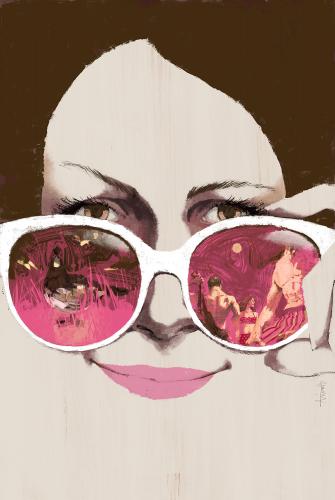

I told her about the all-boy orgy I’d seen across the way the other night while gazing about with my binoculars.

Well, she said, that’s also interesting and does not surprise me one bit. This is Miami Beach. But what I want to know, she said, is about you.

Told her about my mother. After some nudging, about the disastrous men. Sir Gold, Lurch, the Devil. Didn’t mention husband, much.

N thought I ought to meet new men.

Look at you, she said. You’re desirable. You could have … all sorts of opportunities.

Her phone rang, and when she went inside, I looked again at the water, islands, city, sky. A pair of pelicans soared by, coasting so close I could almost touch the ashy fur of their breasts, beaks like oily shell.

When N came out again she said, Is it a fear of flying?

I shook my head. Her wing’s clipped.

N smiled the slow smile. I wasn’t talking about the duck, she said. See? You’re too young to even know what I’m talking about. Fear of Flying. The book. Look it up, smarty. I was talking about you. The unknown, she said. You know. Letting yourself go, all that junk. That’s what you’re afraid of.

Sure, I said. Who isn’t.

Oh, I don’t know, she said, sometimes—

But just then her face, with its disturbing wide smile and liquid eyes, her face like a beatific jackal, got pulled by that pain inside her. She placed a large thin hand on either side of her chair, eyes focused nowhere.

On the causeway, message rolled up in my pocket, I saw again the runner whose body is tattooed, at least the skin not hidden by shorts. Have always thought the patterns were paisleys, but when he passed close, saw they were the seams and striations of red and blue meat: tattoos of the muscles inside.

As I walked and tried to Kegel, of course I thought of Body Worlds: that exhibit of people who’d donated their dead selves to be skinned, preserved, and mounted for view.

It started in Germany when I lived there. Then it traveled all over the world, a caravan of skinless bodies in elaborate poses. Midstride, odalisque, midfuck. I think one peeled body was hitting a volleyball.

It happened to be curated by the husband of my doctor.

And as soon as I thought of it, even the balmy Biscayne Bay air wasn’t strong enough to overcome the smell of that waiting room in Heidelberg, the waiting room in the Frauenklinik. The other fruitless women, bitter with added hormones and subtracted caffeine, sat in wooden chairs against the walls and waited, the floor muddy, smell of old wet stone and must. Every so often a door in the corner would open and a voice would cry Die nächste, and the next woman would get up and look back at us waiting and go into a lit room for blood to be drawn, then into a dark room to take off her pants and lie back and let the probe be jabbed in and tooled around to see if any grapelets were growing. We were to get up and go in the order we’d come, and it was our job to know this order, so each looked up fast when a new harried woman appeared at the door, to be sure she knew her place. I’d memorize each woman’s face, look at the other slumped waiting bodies, and gradually think of the people who’d donated their dead selves to my doctor’s husband, the room slowly blurring into a tableau of peeled bellies and heads.

By then, I’d reached the green verge on the other side of the drawbridge, the duck standing in her station, gazing bravely north at the bay. As soon as she heard my FitFlops, she started waddling to our meeting point by the sea grape. I strewed Grape-Nuts and poured water into the dish, and as she shucked her fear and darted close to begin eating just inches from my foot, I tried again to touch her—fingers nearly on her shiny black feathers—but she flapped away, affronted. Okay, okay. Under the shrub was a plastic bottle; I slid my message inside and tied a pink ribbon around the neck.

Hello, whoever is feeding this duck—please call! We have to save her.

What I now know, having deployed Google:

Muscovy ducks are considered exotic. If I call animal welfare, they’ll euthanize.

Muscovy ducks are not pelicans, as the lady at Pelican Island observed, so no, they will not adopt her.

Two ornithologists at the University of Miami had no idea what to do. Ditto Florida International.

A Muscovy duck website recommended capturing the duck and taking it to a duck shelter.

A veterinarian specializing in exotic animals also suggested capturing the duck and taking it to a shelter.

Both website and vet said that to catch the duck, just grasp it by the neck or use a net.

Balcony, night. Drinking.

The lower sky’s full of glittering buildings, the bay’s full of glittering boats, the water’s full of echoes of both. In the upper sky, Orion tilts along with his belt and starry sword.

Below the sword, in the next condo’s top-floor gym, two men and a woman run toward fogged glass. They look brave and serious as they gleam and stare west.

Five stories down and two windows over, a dinner party. The hostess gets up from the table and walks from room to room, windows lighting as she goes. Alone in the kitchen, she opens the fridge and assembles things at a counter. Three windows over, the guests lean close, an arabesque of light over their heads. The paintings behind them are deep red, green. She sets small plates on a tray that she now carries back from window to darkening window until the group at the table turn their heads, and she’s with them again.

A corner apartment near Star Island is a bordello. This is a fact. A man will come out in underpants, with a cigarette and drink, looking sated as he gazes toward the island where Madonna sometimes lives. Then a bikinied woman might come out and lean against the railing, not near him, and smoke. Never a lot of clothing.

Up to the northeast, over the sea, a point of light grows in the sky. Behind it, a smaller point emerges from darkness. Behind this, another, smaller still. No matter when you look at night, always this configuration of swelling stars, as plane after plane flies down the shore and swerves westward at the Venetians.

Inside, Buster leans against a wall, swaying.

No other movement in my place.

No sign of life at all.

Maybe the digital clock on the stove ticking off minutes as they die, here in la vida loca.

Buster isn’t even swaying; he’s asleep at a slant.

When I couldn’t stand the apartment or Latin or poor Buster’s howling anymore, I went out. Walked east.

As I crossed over the bridge, a yacht passed, beat booming around it. In the cabin, three men with drinks shouted over the music; on the prow lay two girls in bikinis. Both leaned on their elbows, toes pointed toward sea, long hair flitting, long legs bare, bare hips.

A posse of Jet Skiers roared by, musclemen in life jackets, engines roiling the surf. They whooped at the girls, bellowed pleasure and lust. The two sets of men, those on board and those on water, regarded each other, regarded the girls. Then all the men grinned and raised their glasses or fists to toast such splendid possessions.

The boat sped into a red ray of sun, and the girls on the prow: They flamed.

Walked north, away from the lounge chairs and plastic bottles jammed in the sand, walked north by thirty blocks. On the boardwalk: German family, two Latinas talking fast, skinny man selling crickets made of woven palm frond. Music thumped from hotels. But the farther north you walk the quieter it grows, until the boardwalk ends, and wooden steps take you to cool, pale sand.

A photo shoot. A guy was darting and pointing and shooting a young woman wearing only a thong. She rolled in the sand, rose to hands and knees, swung her hair and bare breasts and roared, then swiveled onto her back and scissored the sky, just a string of cloth between her tender inner world and everything else, broken bottles and jets and Dumpsters. Another woman danced behind the photographer, around him, finally pulled up her shirt, pulled it off, and flung herself on top of the other as her legs cut the sky. Three men had settled in solo spots fifty paces away, to watch. Two had their hands in their shorts.

Five blocks north lay something large at water’s edge. From far away: beached dolphin? No: human, but not clear if male or female or what. It twisted, it wriggled; from the waist down, in frills of surf, swished back and forth a fish tail. Above the tail, a naked belly and thin, bare breasts, head flung back, eyes shut, red hair sweeping the sand. No camera to be seen. She stroked her belly with a ringed hand and looked so alone and private I wasn’t sure whether to walk in the water and pass at her tail or walk behind her head. She didn’t care. She swished her sequined tail in the froth, dragged her long red hair in the sand, held both breasts as she writhed, mascaraed eyes shut tight.

Someone is living on this beach, wrote my heel in the sand, to the sky.

When I got home, my phone was flashing. But no text from the Devil or my mother: On the screen was the duck. Sleek black feathers spotted white, delicate barnacles crowning her beak, her pink-ringed black eye baffled.

Hello, duck friend. We must do something! She is getting thin. Can you meet on Sunday?

Yes! I typed with eager thumbs. I’ll bring—

On my way to the duck rendezvous, wondered about the other duck person. The name on the messages seemed to be Xla. Female? Basque? Who cared about this duck?

Good luck with Duck, darling! wrote my mother.

Okay, okay.

Xla and I had agreed to bring water, food, gloves, sheet, pet carrier. The hope was to lure her out, nab her, jam her into the carrier, and transport her to the Miami Beach Golf Club, to join a Muscovy flock.

Stultifyingly hot and bright, and you can’t carry a parasol while catching a duck. Wore a big visor instead, making a disc of shade atop my head that did one-ninth the job. Early July: sun highest overhead?

We’d decided on this awful hour because the duck spends the hottest hours in her shrub.

I got there first, saw the duck huddled in the sea grape. To wait for Xla, I climbed down to the rocks by the water into a thin slant of shade.

Voices. Climbed back up to a black-haired girl and sulky-looking boy in a red baseball cap.

Hello, she and I said. Okay, how shall we do it?

Once it’s out eating, said the boy, we should surround it, and one of us should be holding the sheet, and we should slowly draw in close—

I think we should all three already be holding the sheet and corner her into the shrub, said the girl.

But then it’ll just go deeper in the shrub.

But otherwise she’ll bolt and go into the water, I said.

Or the street, said the girl.

It won’t go into the street.

She might.

Listen, the boy said, I’ve told you how we should do it. You should listen to me. You never listen to me.

I do! cried the girl. It’s just—

No, you don’t, and you want my help, and I do not give a fuck about this duck, but I came here to help you, and now you won’t listen.

Wandered away to see how the duck was doing. Even deeper in her shrub. She was thinner—and trembling. Climbed back down to the rocks by the water to wait the conflict out.

After a few minutes, the girl’s face appeared.

Okay, she said.

Climbed back up.

So what do you want to do?

We’ll put out water and food, and then when she’s eating, he’ll chase her from behind to where you and I are standing with the sheet ready to catch her.

Well, that sounded not likely. But who knew. We all walked away toward the causeway as if we were just casually leaving, and then I acted as though I were just coming to feed her like any ordinary day. I put down a dish of water and strewed Grape-Nuts in a line that would draw her away from the shrub. The three of us quietly got into our positions, not too close to the duck, and waited.

The “A” bus motored by. A moped.

She came out cautiously, gulped the water, and was nibbling at the Grape-Nuts when the boy charged from behind. She fluttered and flapped, galloped past the girl and me, dropped down to the water, paddled off.

The three of us stood on the verge and watched as she sailed away, past anchored yachts, a black-and-white blot in the distance.

Well, I said. She won’t be back soon.

The boy shook his head and walked up to their car.

I guess that might be it, said Xla. He doesn’t think—

I understand.

Yeah. He doesn’t think we should spend our time on a duck.

Okay, I said. Will you still bring water?

Of course! she said as she scampered to the Mazda that was already revving.

Slick with sweat and burning, I staggered back over the bridge and past the Dumpster into the building, barely able to see.

Well, maybe duck likes being where she is, said my mother. Maybe she doesn’t want to leave.

Fine, I said savagely. Except that unless I feed her and bring her water, she’ll die.

Have you thought that maybe you’re keeping her there by feeding her? Maybe if you didn’t, she’d go.

She can’t! Her wing’s clipped! She’s stranded!

There was a pause. Then my mother said, Darling. Don’t you think that perhaps you—

Yes, I said, yes, I know. I know this is not a real way to live. I know this. It’s better to be involved with people than ducks. But right now, you know, I’m on a deadline, and there’s not much time—

And I wrenched the conversation back to her blood pressure and whether she was doing her leg exercises and drinking enough water and eating anything other than grilled cheese, and soon she was sick of me, too.

When I passed by on my walk that evening, there of course was the duck, in silhouette, gazing at the bay.

She warbled and came wobbling toward me for Grape-Nuts, but I just walked right by. Did not even turn my head. Kegeled.

I did not, do not, want to be a weird lady involved only with a duck.

And cat.

I don’t.

Was walking over the drawbridge as a motorboat glided below—a boat like a 1967 Mercedes convertible skimming the milky green. In it: two men, shirtless with firm, bare arms resting on polished sideboards. The setting sun made their skin emit light, and by now my Kegeling had resulted in my own lower glow—because Mr. Body does what it wants and stirs up trouble no matter what you think best, and these men with their smooth lit arms and trunked laps slung into low leather seats—I couldn’t help it, I glided up onto the bridge’s balustrade and with uncommon grace stepped off and floated, floated, gently down, and was caught by the man on the left. He looked surprised but then seemed glad, and said to his friend, Look what I caught. That one glanced over and grinned; he had on sunglasses even though it was dusk. He placed his free hand on my calf, as it seems that I was suspended between the two, my head on the thigh of the other, cheek against a growing plumpness inside his trunks. His fingers—how hadn’t I noticed?—had casually begun undoing my top, and now there were my breasts in the warm blowing breeze, as we motored out to sea!

An active fantasy life is good, wroteN. But I wish you’d find something with a pulse.

Buster had one. Picked him up, his claws like pins in my arm, long tail sweeping my hip.

When I change his diapers, we sit on the cork floor, and I clasp him close between my knees. He stretches out his skinny black legs, tufts of yellowing white fur on his belly, and purrs and purrs when I wipe him clean. As I fasten the pieces of blue tape at each side, his forepaws knead the air, reach for my chin, and he gazes my way with blind glass-green eyes beneath long white whiskery eyebrows.

So peaceful.

Certain songs I used to whistle to him, back when he could hear.

His favorite was Gato Barbieri’s theme from Last Tango in Paris. At the first four notes he’d come bounding.

Yeah, well, what’s wrong with fantasy. From phantasia. Born of visions. Even if Aristotle calls phantasia a feeble sort of sensation. An active fantasy life is good. Self-pleasuring does ward off atrophy.

Atrophy, emotional anorexia, paralysis.

Solipsism?

Oh, for fuck’s sake: One does what one can.

In the middle of the park today, when I was on my way back from Publix with pink umbrella and heavy bags of milk and cherries and litter and cat food, sweat trickling down my arms, N emerged from the shade of the banyan. She stepped into the sun and held up a long yellow hand to stop me, squinting into the blaze from beneath her white hat.

Let me ask you, she said. Do you still have desire?

Blinked the salt-sweat out of my eyes and told her that I did, yes, but only in the abstract. Added a few scientific points about the healthfulness of fantasy, satisfying the need for blood to rush through and plumpen lower tissues and explode, brain simultaneously exploding in stars, etc.

Okay, she said. If you still have desire, you’re still viable. That’s how it goes.

Like an old cat still purring and eating, I said.

Sure, she said. Why not.

Still, one does what one can.

Yesterday two people sent messages about the duck, but not helpful.

Contact Animal Welfare!

Take it to Pelican Island!

Now that I am the duck’s sole tender, saving her is up to me. I elevatored down to the leaking garage and got in the Mini, drove over the Venetian, dollar seventy-five toll and all, ramped onto I-95, and sped along in the white-hot light until 95 dumped me onto Route 1. Then way down Route 1, which ought to run beneath the Metrorail for shade but doesn’t, to a sporting-goods store. Went in and told the man there I needed a net. He was tall with damp-looking bristle on his face.

Fishing? he said.

No. A duck.

He didn’t exactly smack his chops but looked eager and asked how much the duck weighed.

Eight pounds? No. More like a big chicken, maybe six.

He stared at me, eyebrows riding his forehead.

A six-pound duck? he said. Can’t you just grab it?

She bites and is quick, I said. It’s hard.

I won’t transcribe the rest of the negotiations, but $32 later I had a net fixed to a pole. Was excited to try it out.

But as I drove home, the blue sky exploded again, as it does every afternoon these days, so no attempt to capture duck.

Inside in green stormy light, mulling.

Okay, I told my mother that I knew being alone was not a real way to live. But, come on: It’s the realest way. If you tend to a blind cat and stranded duck, and fragments of men drop into your inbox, and you talk now and then to a skeletal lady and wobbling old mother, and text occasionally with people your age, and focus on bringing a dead poet to life, surely that’s enough.

Snow White had seven dwarfs, after all.

Must have added up to something.

I mean it. If a person drives herself around and has her own place and can fix most things or pay someone who can if she can’t and is able to dig up inner resources to sustain herself even in bone-dry moments, absolutely baked and bone-dry moments, and if she has long since decided that for fuck’s sake it’s all right to drink alone—I mean, come on, there’s no one to drink with—and if she’s also decided that self-pleasuring is more than fine, it’s healthsome, especially if accompanied by fantasies drawn from excursions into the world: That’s fine.

I tried this on N today and got her slow sad smile.

It’s good for a person to have another person, she said. It’s good to have a mate.

Was walking toward the drawbridge when a Jet Skier skimmed extremely loud and close, so close he almost ground into the rocks and I could see the sleekness of his skin. He was in black, his Jet Ski was black, and I stopped and looked at his forearms, his strong hands on the horns of his machine.

Then I just stepped gracefully off the bridge and skimmed down, down, slipped behind him, my legs clasping his wet legs, my breasts pressing his taurine back.

Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go to the sea!

Standing up there with bony elbows on the dirty concrete, old feet in cracking FitFlops, as below me he whipped and spun in the water and froth, delighting like a dolphin.

Out of the blue I thought: Look at me!

Now!

He rode on. He drew a huge spraying circle in the green, looped into another circle, digging, churning, cutting deep, dredging and ripping, spraying water and fuel-stink and engine screech, bucking and plowing, all horsepower, manpower.

Something cold stirred within me. I thought: Harm should come to you.

Then forgot about him and walked on past the duck, first island, second, past the old pear-shaped man who goes around with a bag to feed the cats, the old man I am becoming, past the crazy boy who swoops on his banana bike, although he’s way too big and fat for it; he always shouts Hello, I always shout Hello back. Then, walking back, there was the sunset, splendid as always, and a person gets tired of appreciating the damned sunset, having to keep stopping and turning to look at it more.

Enough with the sunset.

Like everyone, a liar. I do appreciate it! Beauty like that—makes you helpless. Makes me walk home stupidly backward, filling eyes with color.

At home, came in around back, along the dock, peering into the water because, you know, that’s living the life.

From the dock, something ahead of me suddenly slid into the bay. Not the first time this had happened: I once startled an iguana sunning on the dock and it slithered fast and plopped in; by the time I reached the spot, it had become a fish. It’s true. There this thing was now, in the water plugging along with a beak and clawed wings batting. I crouched, crawled sideways as it platypussed along. Feathers? Fur? Webbed feet?

Meanwhile became faintly aware of a sound: the kind you hear without properly hearing, whatever the phrase for such ephemeral sensory experience is. Maybe boys shouting on Monument Island, maybe someone singing on a boat, nothing you’d lift your head for.

So didn’t. Kept peering into the water trying to decipher the bird, lizard, or fish.

But then the noise began to lift from the air, to clarify itself in my ear. It was a voice. A man’s voice. A man’s voice shouting Help.

Stood and scanned the bay, darkening, the sun nearly sunk.

Tiny and distant: Help!

In the bay’s swift middle river, a coconut rolled. Far away by the verge, a Jet Ski bucked alone.

But no voice would rise from my throat.

Stone, a tree. Could not speak or move.

But as I stood frozen, from above:

Hold on! I’ve called! They’re coming!

I finally jerked to life, ran down the dock, spiraled up to the pool, through the jungle and the glass doors, into the mezzanine, down the hall to chief-of-security Virgil, who was already running with his walkie-talkie.

I followed him back out, and we watched from the dock as a police boat whizzed under the drawbridge, slowed, circled, and stilled, and a man was pulled from the bay.

Lucky guy, said Virgil. Lucky somebody saw.

Rose to my twenty-first floor, not catching own guilty eye in the mirror. Then opened my door to see just the end of it: Buster spinning, nails scraping crazily at the floor, as if being lanced by lightning. Liquid flew from him—he’d flown out of his diaper—his paws slid and he skidded and slipped, but clambered up because he had to keep spinning.

There’s nothing you can do. Just wait until it’s over, steer him from sharp corners and bruising table legs.

Spinning, the sound of his panting, the clicking of nails on the cork.

Oh, baby cat.

Finally the lightning was spent and he collapsed, puddled black on the floor. I lifted him in a towel and held him close and warm, his little head slumped on my arm.

They don’t know where they are after a seizure, the vet says. Even if they’re not blind and deaf, too.

Sat on the sofa and stroked the fur between his long ears, down his knobby back, in his little underarms, until he slept. Then put fresh tissue in his box and laid him gently down.

My mother’s voice on the phone was soft.

Don’t you think, darling, she said, don’t you think all of this might be telling you something? Maybe—something in your life needs to change.

Well, it was a long time, the marriage in Germany. You can’t help but start to feel it: 100 percent an alien. Ten years there, five years staring out the greasy train window at dawn on my way to the Frauenklinik. Then the greasy train window home again hours later, the greasy window of the tram, and back to our bare apartment sixty-six concrete steps in the sky. Then the wall of windows looking out at the gray, when I’d come in with a fresh bag of vials and needles, to start a new month of trying.

Calendars kept count. First the calendar with a polar bear, lorikeet, pink-bottomed monkey; then the calendar with a ghost gum, baobab, poinciana; then the one with types of rock. I like metamorphic rock most, but you’d probably figure that.

Dry German sun came in the window, on days when there was sun. Otherwise lead air, lead sky, wet weighty cloud. Same ads each season at the tram stops, year after year for ten years, same glares from old men, old women, cigarette smoke in the sooty air, broken bottles, puddles of piss and beer and rain.

Schöne Schlitz, a drunk once said, pointing between my legs. My husband didn’t understand or maybe didn’t hear, always dreaming something else, but anyway, did nothing.

Schöne Schlitz, sure, I thought. Schlitz good for nothing.

In the summer, wisteria grew inconceivably huge from a small pot on the ground out front. It rose lush and weighty all the way to our floor and hung so thick across the wall of glass that it made our place a terrarium, green light. I’d hang little mesh bags of suet and seed in the leaves, bags I bought at Schlecker. Hung four across the wide glass, and sometimes two or even three little bandit birds would peck at a time, as I sat at the white table inside and watched. A pair nested in the leaves each year, those little bandit birds. Two eggs, sometimes three. Watched until they cracked and opened, noisy skinny chicks, flew.

Buster watched the birds, also. Year after year.

And watched me, too, ears alert when I’d sit on the bed again, crying.

Down on the street, seen through a hole I’d cut in the leaves, my husband sat at the tram stop. Sat on the dirty bench with his satchel, holding his face in his hands.

Maybe tomorrow, maybe someday, as the song says.

Finally, when there was nothing left, I split up our things and flew over the ocean. Stayed a time with my mother.

Then, a hopeful tour of disastrous old boyfriends. Lurch, the Devil, Sir Gold.

And then, now.

Just me, dying cat, and duck.

At least I can still try to save that damned duck. It is so hot, nearly August, blistering scorching shattering hot, and from ten until six she huddles in the sea grape waiting for water, for the day to die. I see her there at midday when I can’t stand being inside anymore and can’t stand transmuting and looking for messages, so go outside in the flaming heat under my hot pink umbrella.

The duck is thinner; she trembles.

Enough. Today I am going out with the net. If she’s weak and addled I’m more likely to catch her. I am determined to catch her. Will hydrate, put on the big visor, gather Grape-Nuts, water, and net, and head out to capture this duck.

No duck. Three cars slowed down to watch me try. She waddled toward me as usual, thinking I bore only Grape-Nuts and water, then spotted the net and fluttered hysterically around, hopped down the rocks, sailed into the bay.

I stood roasting with my net. A car pulled over, hand out the window taking a photo. Outside the bridge house the bridge lady watched.

Am done. No more trying to save the duck. Just bring her food and water and let her live her stranded life.

And she’s right, my friend N. I do remember moments, warm, voluptuous moments, what it could be like. One morning, when I was showered and warm and somehow feeling both porous and whole, in he came, into the room with its tall window of live oaks making the light green, the polished wood warm beneath my bare feet. The door clicked shut, and his sudden mouth on my neck felt river-fresh, my panties only just pulled on now slipped off by his fingers as I leaned back on the bed and sighed, my arms stretched over the cotton blanket, as what felt new and morning-clean slid inside to a place that was still blurred with sleep but waking so quickly, suddenly so full of quickness and light and pleasure, pleasure, until each of us was laughing in the other’s laughing mouth. A morning like that, who wouldn’t laugh with delight when it’s wonderful and already done before you even knew you were longing?

Soft skin alive near your own, skin so close it isn’t substance but pure human warmth. So close you can’t imagine aloneness.

And I miss this. I miss it.

But maybe it’s enough to have had some love some time? Even if it worked only awhile? Enough to have had some once and now to live with just pieces of it, and it’s all right if you spend what you still have on an old cat or duck, a few friends, your mother. Not everyone is paired on the ark.

A final try to capture the duck. Did not go prepared. Just saw her as I approached the verge and couldn’t stand it, had to catch her, grab her, take her somewhere else.

Dusk, the grassy verge, the blades moist and tickling, my FitFlops making the thwack at which she turns her head. She waddled toward me as I came near, my eyes on one of her pink-rimmed black eyes, Grape-Nuts in baggie in hand. I did not go to our usual meeting point but stopped in the middle of the grass, crouched, strewed kernels, then moved backward, drawing a path of grains to Hansel-and-Gretel her toward me. She gobbled from the first pile, followed the trail a few inches, but then sensed something and lifted her head. Only four paces from my knees. I should have waited until she came. I should have just been patient.

But couldn’t stand it. I tightened, then sprang—

And the duck! Like everyone, a liar! She fluttered and flapped and suddenly wobbled upward. She beat her wings hard, wavered, and rose, careened toward me, flew above me, rose higher, higher, swerved from the verge, and wheeled up, over the bay.

Jane Alison

Jane Alison is the author of several novels; a memoir, The Sisters Antipodes (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009); and Change Me, translation of Ovid’s stories of sexual transformation (Oxford, 2014). “But I’ve Got Ovid” is adapted from her nonfiction novel, Nine Island (Catapult, 2016). She is Professor and Director of Creative Writing at the University of Virginia.

Marc Aspinall

Marc Aspinall’s clients include the New Yorker, Wired, the New York Times, Financial Times, and Country Life. His “It’s Cold Outside” illustration accompanying the New Yorker review of Inside Llewyn Davis was selected for the AI-AP Best of American Illustration Collection.

No comments:

Post a Comment