Insane Places

January 21, 2021

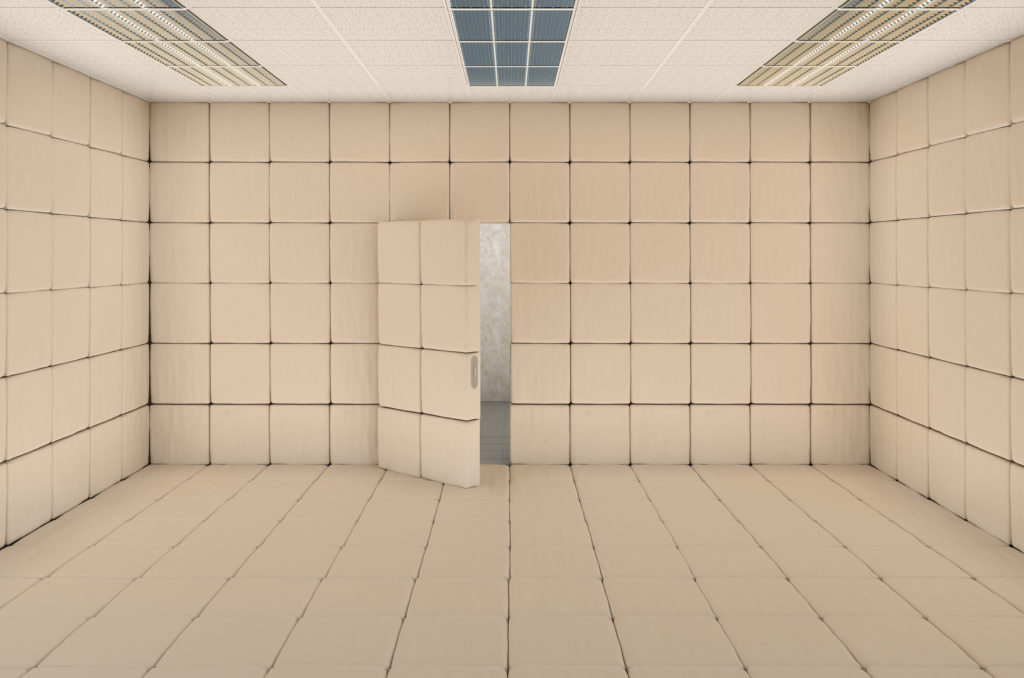

In 1973, the psychologist David Rosenhan published a paper in the journal Science called “On Being Sane in Insane Places.” The paper was based on an experiment he had conducted, sometimes called the Thud Experiment, designed to interrogate how we distinguish the sane from the insane, if in fact sanity and insanity are distinguishable states. Rosenhan arranged to have eight “pseudopatients” seek voluntary admission to a psychiatric hospital. The instigating complaint was of auditory hallucinations: the patients claimed to hear voices saying the words empty, hollow, and thud. All eight were admitted into psychiatric wards, most with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Once in the wards, the patients experienced some initial anxiety—they hadn’t expected to get in so easily—but then proceeded to act normally. Rosenhan writes:

The pseudopatient, very much as a true psychiatric patient, entered a hospital with no foreknowledge of when he would be discharged. Each was told that he would have to get out by his own devices, essentially by convincing the staff that he was sane. The psychological stresses associated with hospitalization were considerable, and all but one of the pseudopatients desired to be discharged almost immediately after being admitted. They were, therefore, motivated not only to behave sanely, but to be paragons of cooperation.

When asked how they were feeling, the patients all said they felt fine and were no longer hearing any voices. But they continued to be treated as though they were schizophrenic. They were kept in the hospital for an average of nineteen days (one for fifty-two days), and when they were eventually discharged, it was under the assumption of “remission.”

Rosenhan (who was himself one of the pseudopatients) came to the conclusion that “we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals.” You could say that the staff were prone to overdiagnosis, that the structure of the institution creates a hammer/nail relation between doctor and patient—or you could say that the structure of the institution creates the conditions for insanity. Rosenhan claimed that, in a hospital setting, “the normal are not detectably sane.” So were they all mad, as in Wonderland? (“ ‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice. ‘You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’ ”) (It must be noted that the validity of the study, and indeed most studies, has been called into question.)

The surrealist writer and painter Leonora Carrington was once, during World War II, institutionalized against her will. Max Ernst, her partner (if that is the right word—they were living together, though he was married to someone else—Wikipedia uses “lover,” which does not sound objective), had been captured by the Nazis. His art was considered degenerate. It seems fair to say that Carrington temporarily lost her mind—war is an insane place. Sickened by injustice, she drank orange blossom water to make herself vomit, to purge herself of the “brutal ineptitude of society”; she saw her stomach as “a mirror” of the world. The sequence of events, by her own account, is confusing, but she managed to escape with two friends from France to Madrid and ended up in an asylum in Santander, a town on the northern coast of Spain.

Down Below, written in 1943, is Carrington’s brief memoir of this period. The doctor was injecting her with Cardiazol, a.k.a. “convulsive therapy,” a drug that induces seizures. Carrington described the occurrence of the first injection as “the most terrible and blackest day in my life”— “How can I write this when I’m afraid to think about it?” (I’m reminded of Sylvia Plath’s first experience with electroshock therapy, which was so physically and psychologically painful for her that she swore to kill herself before undergoing it again.) For ten minutes, Carrington suffered “the Great Epileptic Ailment”: “I was convulsed, pitiably hideous, I grimaced and my grimaces were repeated all over my body.” Afterward, as some kind of antidote, she asked for lemons and “swallowed them with their rinds.” An article on the history of Cardiazol treatment in British mental hospitals, by the researcher Niall McCrae, asks, “What made Cardiazol work—or appear to work?” He suggests that “the intense fear experienced during treatment—the major reason for abandoning Cardiazol in favour of electroshock—was therapeutically advantageous”—that patients, in other words, could be scared sane, which is possibly true. But in the short term, the drug only made Carrington behave more insanely. She became convinced that these “purifying tortures” would help her attain “Absolute Knowledge,” which she needed to unite the cosmos and save the world. It seems the treatments for madness quite often have madness as a side effect.

Carrington’s biography, a friend informs me, is rife with conflicting and erroneous information—perhaps inevitable for a darling of the surrealist movement. André Breton seemed almost jealous of Carrington’s “voyage to the other side of reason,” as Marina Warner puts it in her introduction to Down Below—as if madness were a career achievement. A version of Carrington’s episode in the sanatorium also found its way into a novel, The Hearing Trumpet, written in the fifties or early sixties. But it’s not lightly fictionalized autobiography along the lines of The Bell Jar. Here the experience is transformed into something more fabulist, and much more interesting than the memoir. In the novel, delusions of grandeur become real powers.

The Hearing Trumpet’s first sentence reveals the inciting incident, or perhaps the inciting object, the magic charm that sets events in motion: “When Carmella gave me the present of the hearing trumpet she may have foreseen some of the consequences.” Carmella is Marian Leatherby’s prescient, resourceful friend; Marian is a ninety-two-year-old Englishwoman living in Spain with her son Galahad and his family, who, she has noticed, have ceased to find her worthwhile. Because of her deafness, or perhaps just because she is old, they treat her like vermin or a ghost, as though she were fully insensate or already dead; she enters through the back of the house like a dog. The maid, Rosina, “seems generally opposed to the rest of humanity,” and yet they get along: “I do not believe that she puts me in a human category so our relationship is not disagreeable.” The hearing trumpet, “a fine specimen of its kind,” “exceptionally pretty, being encrusted with silver and mother o’pearl,” is a bit of a monkey’s-paw gift. “Your life will be changed,” Carmella promises—but not necessarily for the better.

Hearing trumpets, an early, analog form of hearing aid, can be quite effective, and Marian’s is, to a frightful degree: “What I had always heard as a thin shriek went through my head like the bellow of an angry bull.” Carmella asks if Marian can hear her: “Indeed I could, it was terrifying.” The impairment had been, in a way, a gift of its own, shielding Marian from the worst of humanity, and her family’s own cruelty. At Carmella’s urging, Marian uses the instrument to spy on her family, and overhears them plotting to put her away. “Your mother has been a constant anxiety to us for the past twenty years,” Muriel, her daughter-in-law, says; their son Robert is less kind: “She’s a drooling sack of decomposing flesh.” They are sure she’ll be “better off in a home,” if not “better off dead,” and in any case unlikely to “even notice the change.”

Marian lowers the hearing trumpet and concedes, to herself, that she may be senile—“but what does senile mean?” The institution where they want to send her, Santa Brigida, run by “the Well of Light Brotherhood,” “sounds more terrifying than death itself”—and yet she has her own ideas about her right to exist (“I consider that I am still a useful member of society”); she is not ready to die and in fact her own mother is still alive, in good health though “getting old”! Marian dreams of going to Lapland, stopping to visit her mother on the way, then spending the rest of her days in the snow among “dogs, woolly dogs.” She doesn’t fight her family’s decision. “Nothing I can say will change your opinion,” she says. “You are right from your own point of view.” She concedes the relativity of reality. Galahad assures her this is for her own good and that she won’t be lonely. “I am never lonely, Galahad,” she replies. “Or rather I never suffer from loneliness. I suffer much from the idea that my loneliness might be taken away from me.”

Because “one has to be very careful what one takes when one goes away forever,” Marian decides to pack “as if I were going to Lapland.” (In 1940, before leaving Saint-Martin for Spain, Carrington “spent the whole night carefully sorting the things I intended taking along with me.” Later, these effects took on talismanic importance: “My red-and-black refill pencil (leadless) was Intelligence … A box of Tabu powder with a lid, half grey and half black, meant eclipse, complex, vanity, taboo, love.”) Marian feels “too preoccupied” to sleep, but then, “sleeping and waking are not quite as distinctive as they used to be.” Day dreaming and night dreaming blur into each other, as in the hypnagogic visions, or near-hallucinations, some people see when they’re falling asleep (Carrington was among them). The next day, Galahad and Muriel drive Marian to Santa Brigida, which is not quite the prison complex that Marian and Carmella had envisioned but “a castle, surrounded by various pavilions with incongruous shapes”:

Pixielike dwellings shaped like toadstools, Swiss chalets, railway carriages, one or two ordinary bungalows, something shaped like a boot, another like what I took to be an outsize Egyptian mummy. It was all so very strange that I for once doubted the accuracy of my observation.

That “for once” is perplexing, because Marian frequently calls into question the accuracy of her observations. Not long after she overhears her daughter-in-law say “she doesn’t have any idea where she is,” which is plainly untrue, she goes into a waking reverie, in her own backyard while, “strangely enough,” also in England, “under a lilac bush.” She knows she is not in England—“I am inventing all this and it is about to disappear”—still, it is England she sees. She speaks of the “fancies” that keep her amused during “sleepless nights,” since “old people do not sleep much.” Or is she sleeping and dreaming all the time? Her room at the institution has trompe l’oeil furniture: a “painted wardrobe” on the wall, “an open window with a curtain fluttering in the breeze, or rather it would have fluttered if it were a real curtain.” Real? All fictive furniture is fake, but this novel has real fake furniture and fake fake furniture. Here the novelist seems to be poking holes and peeking through the text. Sleeping and waking are fluid, as are reality and fiction (or reality and surreality).

Can Marian be trusted? Can Carrington? I’ve heard it said that “all narrators are unreliable,” but the narrator of a memoir is unreliable in a way that the narrator of a novel never is. In Down Below, Carrington writes, of her own behavior, “I did not remember any of this.” We can’t know what happened, we can’t distinguish between the sanity and the insanity in Santander. But in Santa Brigida? Despite her age and infirmities, her bouts of imaginative dozing, as the events of The Hearing Trumpet get more fantastical, I choose to believe that Marian’s version of events is real. What she sees (and hears) in the world of this novel is what actually “happens”: she’s introduced to the bizarre, cultish logic of the institution’s doctrine, “Inner Christianity”; she meets the other residents (or patients, or inmates) and gets wind of their underground schemes; she wonders after the source of a painting of a winking nun, a “leering abbess,” hung across from her place at the dining table; she is given, by a woman named Christabel Burns, a tract about the figure, the whole of which appears as a text within the text (from pages 90 to 126, almost twenty percent of the novel); she witnesses Natacha Gonzalez and Vera Van Tocht making a poisoned batch of fudge, which Maude Wilkins mistakenly eats, dying in the process; she climbs a ladder to peer into Maude’s room through a skylight, and sees the naked corpse of not a woman but a man (cock and balls helpfully illustrated, in one of a number of drawings by Carrington’s son in the book); she joins the other women, all but Natacha and Vera and Maude, in a hunger strike, since eating no longer seems safe. This is survivable only because Carmella has snuck in some port and chocolate biscuits, which the ladies ration and share at night, by the bee pond, where they meet in a sort of witches’ sabbath and trance out in a “weird dance” that seems normal to them at the time.

As Christabel beats her tom-tom and chants, a cloud rises from the pond, “an enormous bumble bee as big as a sheep.” Marian reflects: “All this may have been a collective hallucination although nobody has yet explained to me what a collective hallucination actually means.” What distinguishes hallucination from reality, the fake reality from the real reality, in a surrealist novel? If we believe anything, why not believe this? The weather turns cold, quite cold for Spain—“so cold that hoarfrost glittered over the garden every morning.” The agèd women are underfed and have no fur coats, yet Marian is happy. Because they’re not eating, they can no longer be forced to work in the kitchen. Suddenly they are free. The earth’s polarity is literally shifting. The sun stops rising; day merges into night; they stop using the word day. Marian’s life has changed, certainly. “The sparkling white frost brought a strange joy into my heart, and I thought about Lapland.” Because she could not go to Lapland, Lapland came to her.

On the next-to-last page of The Hearing Trumpet, Marian says, “This is the end of my tale. I have set it all down faithfully and without exaggeration either poetic or otherwise.” It reminds me of a moment in the 1810 German novella Michael Kohlhaas, by Heinrich von Kleist, an aside from the almost invisible narrator, in preface to a strikingly unlikely coincidence: “Just as verisimilitude and fact are not always perfectly aligned, something happened next that we will report, but permit readers who prefer to doubt it to doubt.” We may doubt it, but would we? And why? I love when a piece of fiction insists that it’s true. Inside itself, it always is.

Elisa Gabbert is the author of five collections of poetry, essays, and criticism, most recently The Unreality of Memory and Other Essays and The Word Pretty.

THE PARIS REVIEW

No comments:

Post a Comment