PH Newby

An Exhilarating

Head Trip

The old girl kept writing and complaining about the police. It was enough to start Townrow on a sequence of dreams. Night after night he floated in the sunset-flushed, marine city. He could smell the salt and the jasmine. He dreamed that Mrs Khoury, Mr Khoury and he were all sailing out of the harbor in a boat that slowly filled with water. He dreamed he was in a hot, dark room with a lot of men who argued and shouted. It must have been in the Greek Sailing Club because when a door opened there were oars and polished skiffs; and opposite, high over Simon Artz’s, of the other side of the Canal, was Johnnie Walker with his cane and his top hat setting off for Suez. Or was it the Med.?

So begins P. H. Newby’s Something to Answer For, the 1969 novel that won the first-ever Booker Prize. “The Booker was not, as it is now, a high media event,” Anthony Thwaite wrote in an obituary for Newby in 1997. “I remember the then–sales director of Faber & Faber, the book’s publisher, telling me that the prize probably resulted in no more than about four hundred extra copies.”

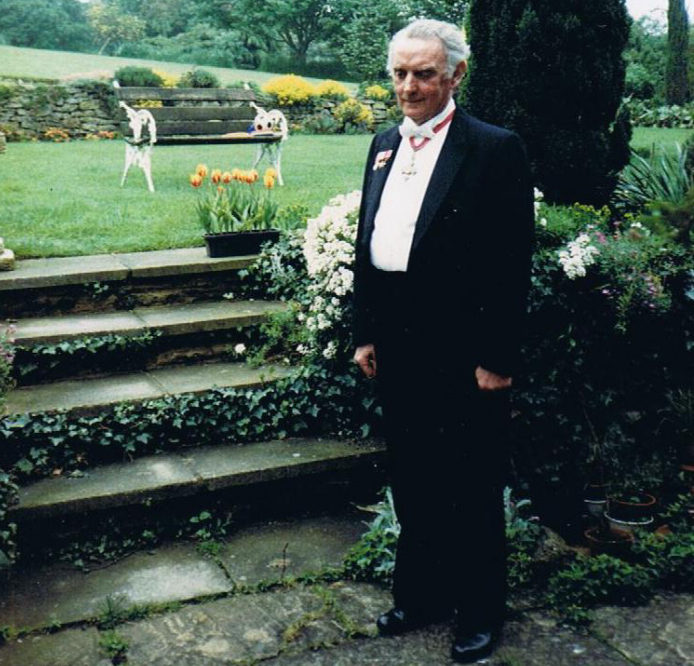

That’s a shame, because Newby, who was born today in 1918, deserved, and deserves, more attention. Graham Greene called him “a fine writer who has never had the full recognition that he deserves,” and that’s as true now as it was in Newby’s lifetime. Very few of his twenty novels are still in print; in the whole of The Paris Review’s archive, his name comes up only once, in Truman Capote’s 1957 Art of Fiction interview: “Well, who are some of the younger writers who seem to know that style exists? P. H. Newby, Françoise Sagan, somewhat.”

In additional to his success as a novelist, Newby enjoyed a long career as a broadcast administrator—he rose through the ranks to become the managing director of BBC Radio. He lived in Cairo from 1942 until 1946: it was “like living in a human laboratory, in which there were no inhibitions,” Thwaite writes, and it informed a number of his novels, Something to Answer For among them.

Something is set in the Egypt of 1956, during the Suez Crisis, and it boasts a wondrous sense of place—but it’s also a deeply interior novel, exploring winding epistemological corridors by way, oddly enough, of blunt force trauma to the head. Its protagonist, Townrow, has sustained some kind of cranial injury, which leaves him increasingly disoriented and destabilizes the text. As Sam Jordison, who in 2007 embarked on a quest to read every Booker Prize–winning novel ever, described the novel’s plot in the Guardian, Townrow

is never quite sure what’s going on—and nor are the readers who follow his bemused progress. He knows he’s gone to Egypt to see the widow of his recently deceased friend Elie and perhaps defraud her of her estate. He can’t say much more with any clarity. He’s unsure for instance whether he saw Elie’s burial at sea or dreamt it. He misremembers scenes and conversations he’s had with Leah Strauss—the woman he’s fallen in love with. He’s overwhelmed by the ongoing events surrounding the ongoing Suez crisis and can’t even remember whether he’s British or Irish, involved or neutral in the whole affair.It’s all very distressing for Townrow, who just wishes that he could “point his mind at something.” For the reader, however, it’s an exhilarating head trip. Scenes are rewritten as Townrow re-remembers them; conversations are willfully and gleefully contradicted; plot strands are wrapped around each other. All that remains constant is the absurd march of history and the brief, bloody Suez invasion, which Newby depicts in a few virtuoso bursts of bracingly sharp detail.

Kirkus Reviews thought of the book as “A little Kafka—a little Greene—a little Ambler, in a charade which is also an expertly agile entertainment poised between the unsuspected and the unknown.”

No comments:

Post a Comment