|

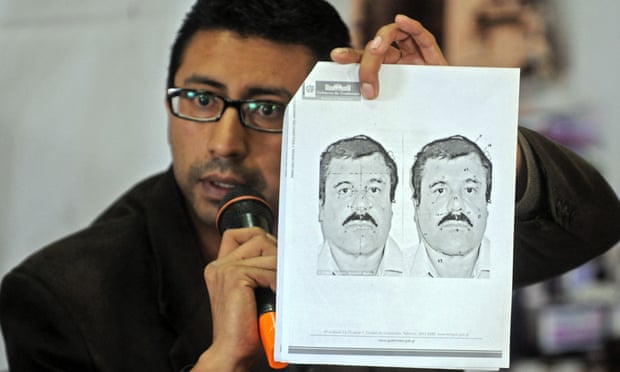

| Mexico’s most wanted … the Mexican military holding drug baron Joaquín Guzmán in 2014. He has escaped from a maximum-security prison for the second time. Photograph: Mario Guzmán/EPA |

Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán: the truth about the jailbreak of the millennium

The Mexican drug lord’s escape from a top-security prison looked audacious at face value, but Guzmán has benefited from inside jobs before. In this bankrupt ‘war on drugs’, the state has more common ground with world’s biggest mafia boss than it likes to admit

Monday 13 July 2015 18.51 BST

At face value, this is the jailbreak of the millennium, and will take some beating. The world’s biggest mafia boss, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, jailed in Mexico’s top-security prison near Toluca after what the US called “the biggest manhunt in history”, slips out after only 16 months inside, through a mile-long tunnel complete with ventilation and conveniently parked motorbike.

Guzmán, recently rated by Forbes as the 14th richest man in the world, is boss of the Sinaloa cartel, the world’s mightiest criminal syndicate, named after the Pacific state of that name, and now proves himself to be arguably the most powerful man in México, whatever beleaguered president Enrique Peña Nieto may think as he scrambles back from a state visit to France.

The escape already looks unconvincing: after all, this has happened before, in 2001, when Guzmán broke out of another top-security jail, Puente Grande, reportedly in a laundry truck. Guzmán ran this previous jail, just as he ran the cartel: a book by one of Mexico’s leading writers on the mafia, Anabel Hernández, reveals that he held extended family Christmas parties inside over several days and that the story that he got out in a laundry truck is a myth – Guzman actually escaped in police uniform, with a police escort, a day after the minister for justice arrived on the scene to react to the “break out”.

This latest escape is also, almost certainly, an inside job at some level (prison governor Valentín Cárdenas has been arrested), but the question is: which level? How deep inside was the escape planned, and how high up the echelons of power?

Guzmán is the last of the old-style mafia dons, nephew of the Mexican godfather Pedro Avilés, founder of what would become the first serious modern Mexican syndicate, the Guadalajara cartel; Avilés was killed in a shootout in 1978. As such, Guzmán commands a pyramid of power as a matter of heredity as well as ruthless violence.

Guzmán is the subject of countless narcocorrido ballads about his gall and banditry. One, by a band called Los Buitres (The Vultures) goes: “He sleeps at times in houses / At times in tents / Radio and rifle at the foot of the bed / And sometimes his roof is a cave / Guzmán is everywhere.” He is the last of the dons who might donate electricity for a local school, flowers to the church on Mother’s Day.

The kind of don who arrived in a smart restaurant while on the run at Nuevo Laredo, deep in the territory of an enemy cartel, had the doors locked by his men, who took all mobile phones from those dining, asked them to continue at his expense while he ate, then left with his posse. Loyal subjects in his native Sinaloa gush their gratitude for – in one case – flying a peasant’s sick child to hospital in his private plane; there were angry demonstrations in the Sinaloan capital of Culiacán when Guzmán was arrested in February last year.

This baronial mafia style is in sharp contrast to the new generation of cartels with which Guzmán does battle, and who rule their terrain with sheer, brute terror; new, leaner and meaner cartels like his main rivals, the insurgent paramilitary Zetas, based in the northeastern state of Tamaulipas, and the smaller Knights Templar in Michoacán. These organisations would rather spend money with less old-style patrimony and more savvy in the vagaries of modern markets.

Cartels are, after all, like any other corporation and follow the same trends as the legal economy; they were never adversaries of capitalism, more pastiches of the “legal” system and often pioneers of it. And in that paradigm, Guzmán, who hails from a cattle-ranching family in the heroin-poppy-growing wilderness of Sinaloa, is old-school.

All this is crucial to understanding why the Mexican state has an interest in conviviality – if not co-operation – with the Sinaloa cartel, just as it did with its predecessor under Avilés and his successor, Félix Gallardo.

Although Mexico’s attorney general has called for a “full investigation” into Guzmán’s escape, we may never know exactly what happened. But if there is a level of complicity by the state, or state agencies, this would not be illogical. Friendly relations between the state and Guzmán would have a rational motive. Not for nothing did the Sinaloa cartel, until recently, have its own hangar at Mexico City airport, not far from the President’s.

In matters mafia, one of the dilemmas is whether it is harder for a state to live with an organised, patriarchal pyramid of power, like Guzmán’s, or the myriad mini-cartels, street-gang micro-cartels, so-called combos and super-combos, that arise if the pyramid is smashed. Which is worse: a formidable power with which some kind of accommodation is possible, or a narco-nuclear-fission reactor of electrons and protons charging into one another?

Colombia had to opt for smashing the pyramid, in the form of Pablo Escobar’s Medellin cartel, because it was becoming a a state within a state that threatened to take over. In the improving situation for Colombians, the problem is now the miasma of uncontrollable combos.

But the Mexican experience is different. The worst violence has ravaged the country since December 2006, when President Felipe Calderón sent the army into Tamaulipas and Michoacan to deal with insurgencies in those states by the Zetas and a cartel called La Familia, which were breaking up the prevailing order of things. Once the hornet’s nest was kicked, the killing accelerated as Guzmán laid claim to the whole frontier (previously allocated by his predecessor Gallardo) and the army and police established mafia systems of their own, often in league with one cartel or another.

In this war, Guzmán and the state have a common cause against the insurgents and new-wave cartels, and it is no secret that Mexico’s best bet in bringing down the violence is to back the strongest and biggest against its rivals, or at least to act in tandem. An official of the ruling PRI party, when it was fighting the last election, talked to me about the need for “adjustments” with the most powerful cartel.

The figures speak for themselves. For a while, in 2008, Tijuana was the most violent city in Mexico, as Guzmán assailed the local Arellano Felix cartel. Soon afterwards, Ciudad Juárez became the most dangerous city in the world, as Guzmán, the local Juárez cartel, army and police factions fought over local drug markets and smuggling routes to the US.

The military went into both places, followed by the Federal police, with Guzmán’s cartel gunmen on the slipstream of both, recruiting local gangs. Now, both cities are relatively quiet; no one knows quite why, but the most common (and terrifying) explanation is that Guzmán now runs the drug business – domestic and export – in both cities, with official or semi-official blessing.

All this falls within a crucial context. The great writer on matters mafia, Roberto Saviano – author of Gomorrah and Inferno – visited the Guardian last week to talk about international organised crime. Among his points were that “we must not think about what is happening in Mexico as far away in some distant land”, and indeed we must not.

For a start, it is thanks to the 120,000 dead and 20,000 missing in Mexico’s narco-war that mountains of cocaine go up British, European and American noses. Everyone wants to forget that Britain’s biggest bank, HSBC, was caught, and admitted, laundering Chapo Guzmán’s giddy profits, as was Wachovia bank, a subsidiary of Wells Fargo: hundreds of billions of dollars of Sinaloa cartel blood money, handled with effective impunity inasmuch as no one in either instance was prosecuted, let alone jailed – indeed, most were promoted.

The logical conclusion is what Saviano, his Mexican counterparts Lydia Cacho and Hernández (and I for that matter) have been arguing for years: that the “cops and robbers” model of reaction to events like Guzmán’s escape – indeed, the whole farce of the “war on drugs” – is bankrupt; that the idea of our healthy society fighting outlaw criminals is fantasy. The antics of HSBC and tradition of conviviality between the Mexican state and Guzmán’s cartel turn the idea of some line the sand between criminality and legality into a brazen lie. Just as Guzmán and the new cartels operate within the logic of the “legal” economy, and become major investors in it, so the “legal” economy and polity embrace the cartels.

Whether Guzmán will continue to run his cartel from hiding again is arguable, but he is hardly likely to abdicate having pulled off a coup like Sunday’s escape, whatever it was. He may try a run to Guatemala, where he was arrested for the first time in 1993, or just return to where the “biggest manhunt in history” supposedly failed to find him for 13 years, right where he would obviously be, at home in his villa. Right there in Sinaloa, where Guzman’s mother was found and interviewed by British film-maker Angus McQueen for his movie The Legend of Shorty, and where the army, Guzmán’s bodyguards told McQueen, was paid to turn a blind eye.

In Tijuana and Juárez, meanwhile, the product keeps rolling, and the killing has abated; last April counted the lowest murder rate in Juárez for nine years. Bars and shops have re-opened along Juárez Avenue, including the one in which the Margarita was invented; people on the streets and families head out for dinner for the first time in ages. Meanwhile, Guzmán, free again, counts the money.

In Italy, it was always known as Pax Mafiosa – mafia peace – and, according to the twisted logic that admits the lie of a line between legal and criminal, it works.

• This article was amended on 14 July 2015. An earlier version said Guzmán escaped from Altiplano jail in 2001; he escaped from Puente Grande in that year. The year that President Calderón deployed the army against the drugs cartels was 2006, not 1996; and the Knights Templar cartel arose in the state of Michoacán, not Jalisco.

DRAGON

Mexican drug lord Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán escapes from prison again

Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán / The truth about the jailbreak of the millennium

El Chapo's escape humiliates Mexican president: 'The state looks putrefied'

Mexican drug lord Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán escapes from prison again

Joaquín 'El Chapo' Guzmán / The truth about the jailbreak of the millennium

El Chapo's escape humiliates Mexican president: 'The state looks putrefied'

DE OTROS MUNDOS

No comments:

Post a Comment