Jeremy Irons: ‘I love villains, I identify with them’

‘Brideshead Revisited,’ ‘The Mission,’ ‘The French Lieutenant’s Woman’… these are just some of the titles in film and television that forged the career of this great British actor. Irons originally intended to be a musician, but his physique, voice and acting skills led him down the path of cinema. EL PAÍS spoke with him in Seville

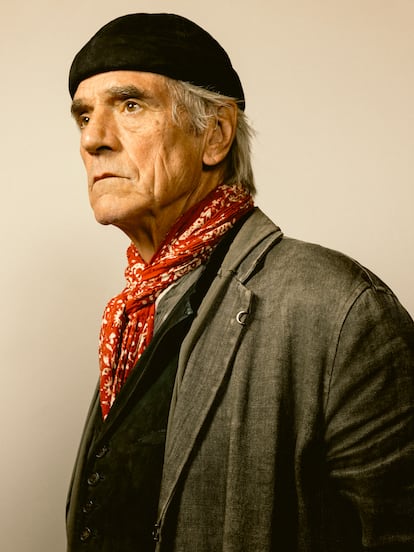

He shows up alone, without a manager, and refuses to go through makeup and hairdressing. We don’t even talk about styling. It’s impossible to separate Jeremy Irons, 76, from the image he has carefully cultivated: that of a gentleman who has fled the countryside. He wears a scarf around his neck, a docker cap, jeans, cowboy boots and a worn, woolen vest.

The Alfonso XIII hotel in Seville is buzzing with a Bollywood-style Indian wedding. However, the staff open up a lavish lounge for the interview, away from the hustle and bustle. Irons looks out the window — he wants to smoke.

It’s cold outside and more showers are forecast. But there’s no discussion: we improvise a little lounge with armchairs under an awning in the garden’s viewing point. Irons is known for chain-smoking. He rolls his cigarettes with the help of a machine. In just a couple of hours, he’ll churn out four.

“Vices... they’re so necessary,” he excuses himself, with a rueful smile.

The illustrious protagonist of films such as Damage (1992) or The House of the Spirits (1993) attended the Seville European Film Festival as a jury member this past November. He also picked up an honorary award for his career and participated in a talk with producer David Puttnam about The Mission (1986), the film that brought them together. They remain friends and neighbors in the south of Ireland, where the actor bought a castle in 1998.

Irons arrived in Seville from Los Angeles, shortly after Donald Trump won his re-election bid. It was inevitable for the interview to begin with a question about the results.

Question. How do you feel about Trump’s return?

Answer. It’s been a letdown, although many foresaw it. Los Angeles is usually a Democratic stronghold, but [people took in the results] without much drama. Perhaps nobody expected such a substantial victory. The [attitude] seems very similar to that of Brexit: people saying “nothing has changed, we want change.” And Trump promised disruption. Disruption may be good, but at what price? To me, it’s a worrying cost.

Q. What kind of world do you see behind this political shift?

A. Hard times await us. We couldn’t be looking at a worse scenario for Gaza, for Ukraine, for relations between Europe and the U.S., or between China and the U.S. We’ll see. I don’t think the opinions of actors will be particularly useful… but it’s clear that it will be harder to enter the U.S. and that many people will leave the country.

Q. Had you visited Seville before?

A. Yes, 20 years ago I was here filming Kingdom of Heaven (2005), with Ridley Scott. I think the Royal Alcázar (a historic royal palace) is in it. I remember seeing wonderful flamenco in some tablaos. I hope to repeat the experience.

Q. The Mission, where you played a Jesuit missionary, touches on conflicts that are still alive three centuries after the time period depicted: colonial extractivism, genocides, impositions of creed, white supremacy... have we evolved so little?

A. There are problems that never disappear and [constantly] affect the public.

Q. That shoot is surrounded by myths. One says that they brought George Martin — the producer of the Beatles — to teach you to play a vintage oboe for the Indigenous people portrayed in the film. Is that true?

A. True. The 18th-century oboe is a very difficult instrument to play. Martin lived in the Caribbean and we were filming in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia). He was so generous. I tried really hard to get the melody right, only to find out that it had been dubbed with Ennio Morricone’s studio recording [laughs].

Q. Let’s continue with the myths. Is it true that you traveled all over Spain on a motorcycle?

A. Yes. From Bilbao to Málaga, via Madrid. There are many great [routes] for bikers in Spain. We have a club: the Guggenheim Motorcycle Club, organized by Thomas Krens (former director of the Guggenheim Foundation), along with Dennis Hopper, Lauren Hutton, and Laurence Fishburne. The wife of a great French architect was also a member... I’m remembering more and more (he’s referring to Catherine Richard, Jean Nouvel’s ex-wife).

Q. Architecture means a lot to you. You’re a friend of the Italian architect Renzo Piano, aren’t you?

A. Renzo is a great friend. And yes, I’m very interested in [architecture]. If I hadn’t been an actor, I think I would have been an architect… although I was never a very bright student. I love it when a space works and feels comfortable.

Q. You came to Spain for the first time when you were 15, to Gibraltar. How was that experience?

A. I came to my brother’s wedding. After sailing here and there, he spent some time in Gibraltar. He smuggled cigarettes into Spain. He fell in love with an English nurse who worked in Marbella and they got married. I came to be the [best man], hitchhiking from France. He made me drive his car — full of cigarettes — down the roads along the coast. I didn’t even have a license; it was the first time I used the gear stick. We lived on the boat, in the port of Estepona. The trip was the most exciting thing ever. People don’t hitchhike anymore. I imagine it’s because of fear. It’s a shame we’ve become so afraid of each other.

Q. You were never afraid of hitchhiking?

A. Not really. I was young and wanted to see the world. I hitchhiked a lot. The guitar fed me. I lived the fantasy of the traveling musician.

Q. Is that why you like to say that you always wanted the life of a gypsy nomad?

A. Yes, I always found it to be a very attractive lifestyle. And I wanted to keep doing it. I didn’t know how. When I decided not to be a musician, but an actor instead, I finally achieved that gypsy lifestyle: I travel, I work with different people in a very close way… and I disappear. I’m lucky.

Q. And that’s why you chose to keep living between London and Ireland, fleeing the siren song of Los Angeles?

A. Yes. I couldn’t bear to spend half my life having lunch and stuck on a highway and the other half filming. I listened to my needs, without worrying about the insecurity of my profession. It’s important if you want to dedicate yourself to this. Especially when you’re a young actor, who doesn’t know when the next job will come. You have to be consistent with the way of life you choose. I did all kinds of things: I cleaned houses, looked after gardens, restored and sold antiques… anything so I could keep studying acting.

Q. Do you remember your first role?

A. I was 12. I was playing an Agatha Christie-type detective in a mystery play. There were no girls at my school. My character wore tweed skirt suits. The teacher who was directing said to me: “Don’t forget to tuck your skirt down when you sit down, like a girl would.” And, of course, I did the opposite: what boys do, pulling up the leg. It’s the first time I remember making an audience laugh.

Q. Were your parents there to see it?

A. No. It was a school play, they weren’t interested in that stuff. I did a few other plays in high school and kept failing [classes] because I was always rehearsing.

Q. Did they think it was a good idea for you to be an actor?

A. My father, who was an accountant, didn’t really agree [with my choice]. He told me that actors don’t manage to keep their marriages going (Irons has been married for 52 years to another actor, Sinéad Cusack, from Ireland) But he also said to me: “If you’re serious about it, just go for it.” He tried to encourage my brother to join the Navy, but he couldn’t convince him. So, when my time came, he supported me.

Q. You were born on the Isle of Wight. That’s where the legendary rock festival was held in 1968, where Jefferson Airplane and T. Rex performed. You were 20 at the time. Were you one of those crazy hippies who went there?

A. Ha, ha, ha! I wish I was. I was working in Bristol at the time. And, from there, I moved to London as a volunteer with the Church [of England].

Q. So you skipped all the “sex, drugs and rock n’ roll” of the swinging 1960s?

A. Of course I bought Beatles records and all that stuff. But I was at drama school and I started working: first cleaning sets and then getting more and more prominent roles..

Q. You’ve said that could have been a vet, a circus artist, an antique dealer, a social worker, or a musician. What’s become of all those interests?

A. I decorate my own houses. In fact, my travels are a great excuse to rummage through flea markets. And music is always with me. I’m now learning to play the viola.

Q. How many instruments do you play?

A. In my youth group, I played drums and the harmonica. And, thanks to the guitar, I learned to flirt. I wasn’t very talkative with girls, but when I sang, they would just sit there, listening. Later, in London, I played the organ for a charity. I’ve never been very good at any instrument, but I really enjoy it

In Ireland, everyone knows how to play music. It’s the evening entertainment: getting together with family and friends to play music and have a drink. One of my favorite things in the world is to sit in a pub with my pint of Guinness and play with people. I do it often. In Skibbereen, a small coastal town in the south, near Cork.

Q. That’s where you bought a castle when you turned 50… around the time when Hollywood stopped calling. How did you deal with that crisis?

A. It was a difficult time, a period of readjustment. [The lack of acting jobs] was one of the reasons why I bought the castle and started working on it, to occupy my time and put the business aside for a bit. I spent about three years without filming, building a very cozy home. If I’m not in London or travelling, you can find me there. It’s my happy space.

Q. You’ve always surrounded yourself with water. You grew up on the coast, you usually swim in open water and you’re an accomplished sailor. Do you spend hours looking at the sea, like Meryl Streep did in The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), the film that made her famous?

A. [Laughs] I cannot carry a tragedy as romantically as she can, but yes, I need to be near water. The calm and danger of the sea, that contrast, is almost a reflection of my personality. As a child, there was a harbor just below the garden of my home. So, at the age of five, I already learned to sail. The sea is in my blood.

Q. You gave yourself until the age of 30 to make your way in the world of acting. You ended up achieving your goal at the age of 33, with the success of the TV series Brideshead Revisited (1981). Today, however, an actor who hasn’t taken off by 25 has a hard time. Your son, Max Irons, is also an actor. Would you say you had it easier than the current generation?

Q. I was very lucky, because [back when I was starting out], there were many theaters in England; you could jump from one to another, learning along the way. My son, for example, missed that. Today, TV series are the standard [cultural] reference. And many people become actors in search of fame. I just wanted to work, to tell stories. I wasn’t a natural talent, but I improved as I enjoyed it. My career was progressive. But I never thought I would have money and fame.

Q. Is it easier to handle success when you have a greater level of maturity?

A. I went from precariousness to suddenly seeing my face in the newspapers, [because I was] starring in the TV series of the moment. Becoming a public person overwhelmed me a bit. Suddenly, the world is your village: people greet you in the street. I can say that I haven’t had unpleasant experiences… people tend to be kind to me. It’s also because I’ve never been too famous. I live a fairly normal life.

Q. You often say that you like characters who are hiding some sort of secret. Does this have to do with your obsession with privacy?

A. Probably. And also with my fascination with people who don’t reveal everything to you right away. I need discovery… that call to go deeper, the mystery. And that’s reflected in my work.

Q. Is it true that you turned down being James Bond up to three times?

A. More or less. Cubby Broccoli (Albert R. Broccoli, the legendary producer of many original 007 films) came to see me. There was a possibility… but I wasn’t enthusiastic about the idea. After Sean Connery and Roger Moore, they chose Timothy Dalton. Looking back, I was probably wrong: it wouldn’t have hurt my career at all. I don’t know. I’m so happy with everything I did at the time that I don’t miss James Bond in my filmography.

Q. At 76, you’ve won an Academy Award, two Golden Globes, three Primetime Emmy Awards and a Tony. Some actors find awards insulting. Do you?

A. I’m not too worried. The truth is that I don’t need awards. It’s always nice to receive one, but in the end, it’s just another object gathering dust on a shelf.

Q. We’ve seen you in very few comedies. Have you avoided them?

A. The producers haven’t seen my comic side. People get an idea about you. Obviously, Brideshead Revisited and The French Lieutenant’s Woman marked a dramatic trajectory that would be cemented with Reversal of Fortune (the film that earned Irons an Academy Award for Best Actor in 1990). And that’s what they saw in me… something enigmatic, not necessarily comedic. But that’s okay, because comedy on-screen is very difficult. You need writers who really understand your funny side.

Q. There was a time when you mostly played period characters and wealthy, repressed and arrogant gentlemen. Did you feel pigeonholed?

A. I may have made 100 films, but people often stick to one or two roles. And they might think I should always play the bad guy. My acting range is broader than that. [Being identified as] as an upper-class guy must be because of the way I speak… but I’m not a gentleman, I can guarantee

Q. You won’t deny that you enjoy playing the villain. You even voiced the bad guy in The Lion King (1994).

A. I love villains. They’re much more fun to play. People who live outside the law are always interesting… I identify with them.

Q. Would you say that with Dead Ringers(1988) — the David Cronenberg film where you play twin surgeons who self-destruct — you reached your most disturbing peak?

A. Yes, it’s probably the most disturbing thing I’ve ever done. But you have to blame Cronenberg [laughs]. It’s a great film.

Q. During the most successful stage in your career, you delved into a different kind of sexuality on screen: the gay soldier in Brideshead Revisited, the politician with a toxic relationship with his son’s girlfriend in Damage (1992), the diplomat who falls in love with a trans spy in M. Butterfly (1993), the pedophile in Lolita (1997)... what has this exploration brought you on a personal level?

A. Our sexuality is a big part of all this. Of living, I mean. I don’t know how I ended up transferring it to my career, but it turned out that way. To delve deeper into a role, you also have to delve deeper into a character’s sexuality.

Q. Did you turn down playing Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs?

A. Yes. That was probably a mistake, though I would never have done it as well as Anthony Hopkins. But I realized I was starting to accumulate too many strange characters, dark types.

Q. You’re going to reunite with Glenn Close in the comedy Encore (still in production), where a group of retired actors meet at a nursing home and put on a play. Who would you reunite with in such a scenario?

A. [Laughs] I would bring Glenn, that’s for sure. And Meryl Streep. My old friends. Although, to be honest with you, I don’t think I’d be happy in a community like that. I’ve never spent my time around actors, except when I’m working. For me, it would be a nightmare. Maybe I would be their nightmare.

Q. What’s your idea of happiness today?

A. When I was young, I used to think that the epitome of wisdom — and what I should aspire to — was to sit happily under a tree. And I found that tree; it’s very close to my home in Ireland. I sit under its shade, look at the landscape and I’m completely happy.

No comments:

Post a Comment